Eighty years ago this month, the U.S. Navy inflicted the decisive defeat of World War II in the Pacific against the marauding Japanese. At the Battle of Midway, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost four aircraft carriers and irreplaceable planes, pilots, and aircrews. The defeat was total, and it wrested the initiative for the prosecution of the war from the Japanese enemy.

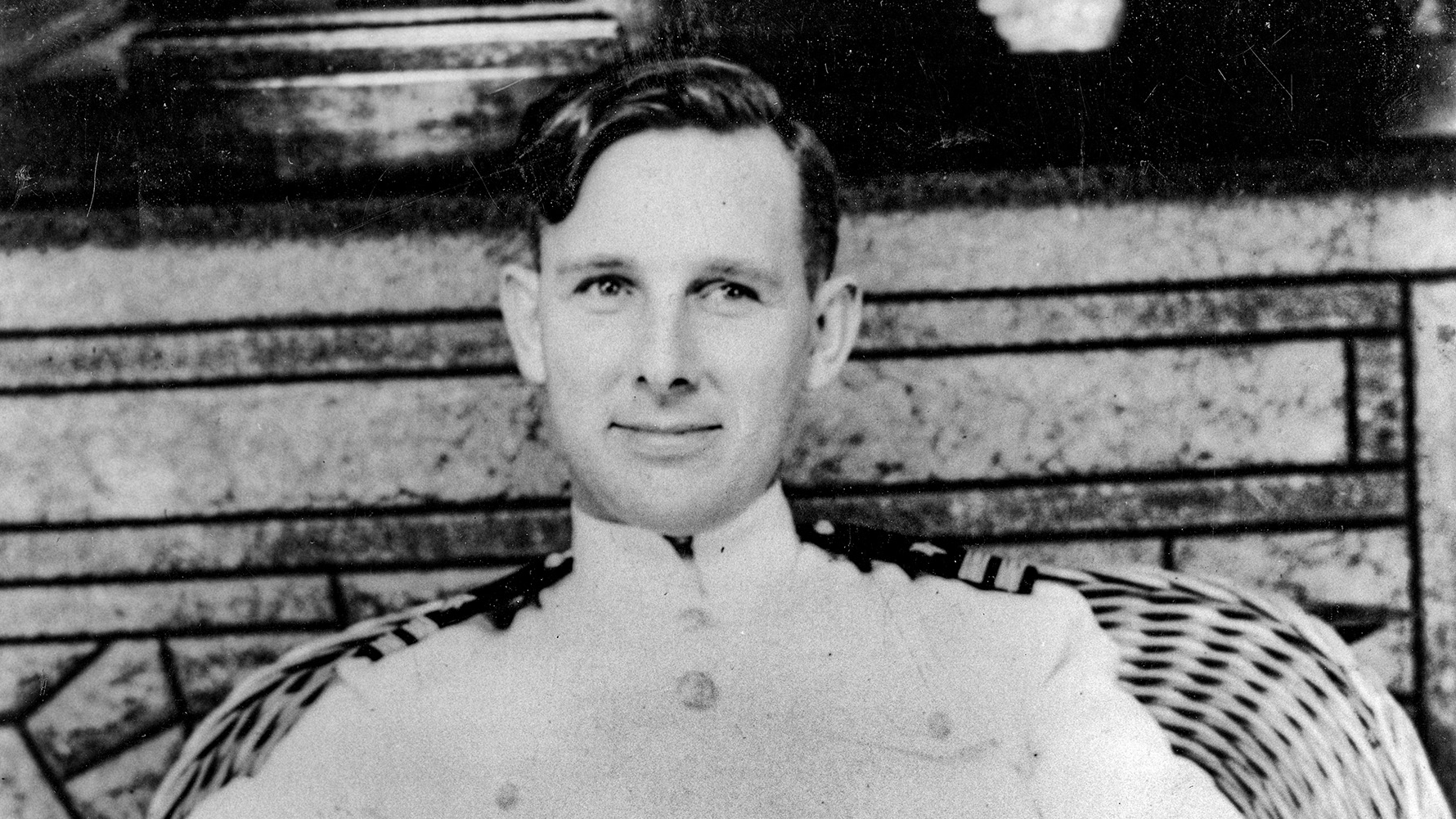

The victory at Midway was a near-run thing. And much of the credit for it goes to the cryptanalysts at Station Hypo in Hawaii, ground zero of U.S. Naval Intelligence in the Pacific, headed by Commander Joseph J. Rochefort, the epitome of the eccentric, nonconformist officer who spurned convention—but more than compensated for it with absolute brilliance—later paying a heavy price for his perspective on Navy protocol.

He was detailed to cryptanalytic training, and his aptitude for codebreaking led to a long association with OP-20-G, the organization created within naval communications in the mid-1920s. He became fluent in Japanese. An early success was the cracking of a substantial percentage of top-secret Japanese radio traffic in JN25B, their naval operations code.

After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy was crippled. However, a defensive effort had to be mounted to first stem the Japanese advance toward Port Moresby, New Guinea, and the threat of an invasion of Australia. The Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, ended in a tactical Japanese victory but a strategic victory for the U.S. in that the invasion force headed for Port Moresby was turned around.

At the same time, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Imperial Navy’s Combined Fleet, had devised a plan to seize Midway and threaten the Hawaiian Islands. Rochefort knew something was afoot, but the questions were just what the Japanese intended to do, where, and when.

Station Hypo played a hunch that a repeated JN25B reference to “AF” was indicative of an offensive move against Midway atoll. Rochefort convinced Admiral Chester Nimitz to bait the Japanese with a false message regarding a shortage of fresh water at Midway. The transmission caught Japanese attention, and soon there was a pronounced buzz concerning the shortage of fresh water at “AF.” Further, Rochefort gleaned the approximate date of the Midway offensive as early June, probably the 3rd or 4th. Again, he was correct.

Nimitz deployed the limited resources available, Task Forces 16 and 17, to a rendezvous at “Point Luck,” northeast of Midway. The rest, as they say, is history.

As for Rochefort, his unconventional style made ripples through the crusty naval hierarchy. He often padded around Station Hypo wearing a bathrobe and slippers. He spent hours at a time immersed in cryptanalysis, without emerging to see the light of day. His intelligence coup was at odds with the brain trust at OP-20-G in Washington, and when he was proven correct it was an embarrassment to the officers in charge there.

In the aftermath of the Midway success, Nimitz recommended Rochefort for the Distinguished Service Medal, but King quashed the initiative. Rochefort was shuffled out and given command of a floating drydock in San Francisco Bay. He retired from the Navy in 1947 but came back

in 1950, concluding his service three years later with the rank of captain. He died at the age of 76 in 1976.

Regardless of Rochefort’s contribution to the victory at Midway and therefore to the triumph in the Pacific War, it was only over the vehement objection of King that Rochefort received the Legion of Merit as the war ended. Still, it took 43 years for Rochefort to receive the Distinguished Service Medal. That took place in 1985. A year later, he received a posthumous award of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Both were long overdue, and it seems a miscarriage of justice that personal enmity should strangle the recognition due Rochefort and all those who made such monumental contributions to victory in the Pacific at Station Hypo.

—Michael E. Haskew

The Navy was always more stratified than the other services. Those serving in the higher ranks were always uneasy about “tradition” being being criticized from below. Rochefort was finally recognized in a couple of films and the names of some of his critics have been properly forgotten.