By John Brown

Three months before the Indian Rebellion of 1857, British East India Company officials manning outstations in the northwestern provinces of India began to notice the revival of a strange and disturbing local custom. Native runners were circulating at night through the villages in the region, bearing small, unleavened wheat cakes known as chupatties. These chupatties, insignificant in themselves, were symbols of a growing unrest in the enormous British colony. According to local custom, anyone partaking of the chupatties committed himself to obeying any orders his village elders might give him. No one yet knew what shape those orders would take, but worried officials passed along their concerns to district superiors in Calcutta. They were told in no uncertain terms to quit worrying about “these local substitutes for a hot-cross bun.” The company, after all, did not tolerate “croakers.”

Given the astonishing disparity of numbers between the natives of the Indian subcontinent and the British members of the East India Company who effectively ruled them, company officials would have done well to heed the rumblings of discontent. The notion that native unrest might actually flare into open rebellion, however, was the last thing on their minds. Since the founding of the company raj in 1600, militarism and war had been more or less a way of life for the British in India. The 125,000 British civilians—men, women, and children—living in small cantonments amid a native population of 250 million, must have felt that they were in a state of perpetual siege. The cantonments, usually a mile or two outside the towns they dominated, were a combination of military barracks and English village, complete with homes, shops, churches, and social clubs. (Read more about the history of the British Empire, from Henry V to Operation Market-Garden, inside Military Heritage magazine.)

A Dissolution of Loyalty

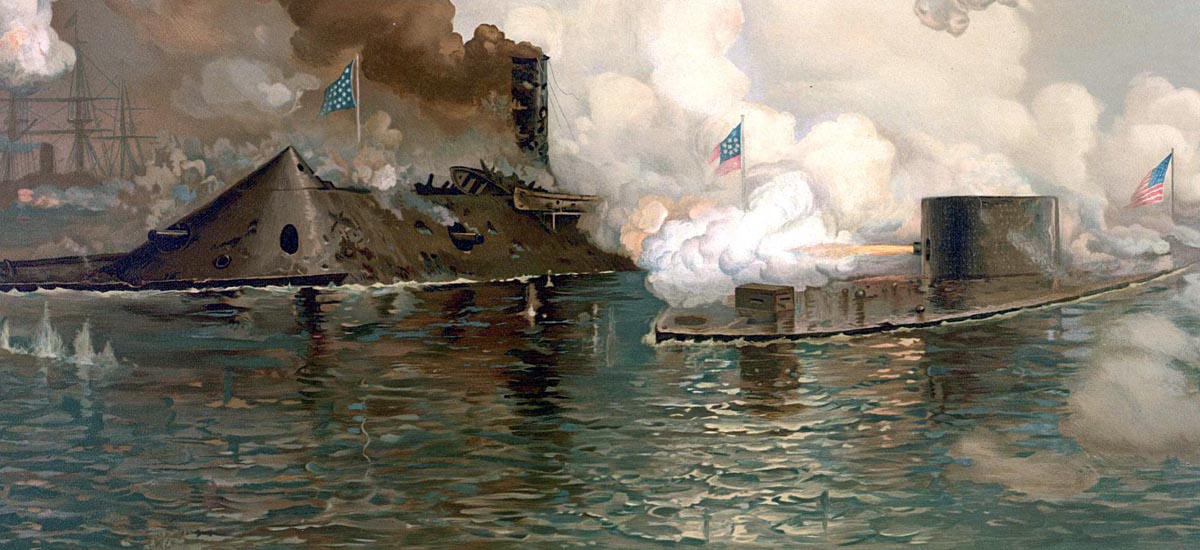

The company’s military organization, upon which its control was based, consisted of British-officered native infantry (sepoys) and cavalry (sowars), British troops belonging to the East India Company, regular army troops stationed in India and subsidized by the company, and irregular cavalry associated—formally or informally—with the company. At the height of its power, the East India Company administered three separate armies based in Calcutta, the British capital of India; Madras; and Bombay. These armies totaled over 250,000 men, of whom some 43,000 were British officers and enlisted men. Most of the company’s sepoys and sowars were members of the Hindu faith and belonged to the so-called Bengal Army, headquartered in Calcutta. Caste-ridden and clannish, many of them were from the recently annexed kingdom of Oudh. They looked down on the native troops of the Madras and Bombay armies, who were drawn from many regions and classes in the far-flung country. Sepoy loyalty was largely a matter of caste honor and soldierly professionalism, not affection for the East India Company and its alien culture. Over time, partly as a result of the company’s financial and military success and partly through the forceful personalities of company officials, native loyalty achieved a tenuous hold on the indigenous soldiers.

That loyalty would be severely shaken by the events of the late winter and early spring of 1857. The sepoys, as professional soldiers, expected to be treated as professionals. Instead, for various reasons, they came to feel that they were being treated with disrespect. In earlier times, a brotherly trust had developed between the sepoys and their British officers, many of whom had taken Indian wives and mistresses and adopted a more or less Indian style of life. Now many of the officers had British wives, snobbish memsahibs who, along with other wives and children, had withdrawn into the exclusivity of a faux-British lifestyle in their cantonments. Consequently, the officers’ traditional rapport with their troops had broken down, particularly in the Bengal Army. Adding to the sepoys’ discontent was the arrival of more and more Christian missionaries from Europe, creating a growing sense of intrusion into India’s ancient religions and beliefs.

The spark that lit the smoldering flame of Indian resentment flared first at Bahrampore, Bengal, in February 1857. There, members of the 19th Native Infantry had refused to accept—or even touch—newly issued paper cartridges for their muzzle-loading Enfield rifles. The Enfields, which had replaced the company’s old smoothbore percussion muskets, used paper cartridges containing powder and ball. The cartridges were greased for lubrication, and soldiers had to bite off the end of each cartridge before ramming it down the barrel of their guns. A rumor ran through the Bengal Army that the grease used to lubricate the cartridges was made from pigs, which were anathema to Muslims, and from cows, which were sacred to Hindus. It was an intentional device, the rumors maintained, by which the British planned to defile the sepoys, break down their castes, and convert them to Christianity.

Indian Mutineers Were Dubbed ‘Pandies’

After a tense standoff between the sepoys and their British comrades, the 19th Regiment was ordered disbanded by Governor-General Charles Canning. Meanwhile, the unrest spread to other native regiments. On March 29 an incident took place involving an enflamed sepoy of the 34th Native Infantry named Mungal Pandy. The colonel commanding the regiment, S.G. Wheeler, was a so-called “New Light,” a born-again Christian who frequently belabored his troops with unwanted sermons. On the parade ground at Barrackpore, Pandy suddenly broke rank, calling on his comrades to rise up and resist the new cartridges. General John Hearsey rode up to Pandy and defied him to shoot; the badly rattled soldier shot himself instead. Pandy survived his suicide attempt, only to be hanged for mutiny 10 days later. His name would become the generic title given by the British to all subsequent Indian mutineers—pandies.

The reports of unrest quickly reached the government at Calcutta, which responded by directing that only British troops should use the factory-greased cartridges. The sepoys could grease their own cartridges with beeswax and vegetable oil. But by then it was too late; the unrest was spreading. On May 10, the dissatisfaction erupted into open revolt at Meerut, 40 miles north of Delhi. Earlier that month, 85 sowars of the 3rd Light Cavalry had refused to accept the now-infamous cartridges from their aged commander, General William “Bloody Bill” Hewitt. In response, Hewitt had the sowars arrested and court-martialed. While the sowars languished in jail, mysterious placards began appearing in the nearby bazaars, calling for the murder of all Europeans in India. On the day of sentencing, the sowars were led into the open square at Meerut, where their sentences were read aloud, their uniforms stripped from them, and shackles and chains placed on their arms and legs. In deathly silence they shuffled from the parade ground.

The next day, at five in the afternoon, Meerut exploded, signaling the start of the now-legendary Indian Rebellion of 1857. While many company officers were napping through the intense heat, the disgruntled sepoys and sowars buckled on their weapons and began running through the cantonment, shooting, looting, and setting fire to bungalows and other buildings. They broke into the arsenal for more weapons and released the imprisoned sowars from their cells. Joined by mobs from the bazaars and convicts newly freed from the local prison, the rioters set upon unwary soldiers returning to camp. Several soldiers were stoned or stabbed to death, an officer’s pregnant wife was eviscerated by a Muslim butcher, a woman suffering from smallpox was pelted with flaming torches and burned alive, and the cantonment quickly became littered with white corpses. By the time the soldiers had managed to regroup on the parade ground, 50 men, women, and children lay dead, and the rebellious sowars had galloped out of Meerut on the road to Delhi, followed on foot by hundreds of maddened sepoys.

The next day the rebels arrived at the palace of the old and nearly helpless king of Delhi, Bahadur Shah, the last and least of the Mogul emperors. Bahadur Shah, an opium-addicted octogenarian, was king in name only; he was paid a paltry pension by the British, who were merely waiting for him to die to phase out the Mogul line altogether. The king retreated into his palace and summoned his keeper, a company captain named Douglas, who told the mutineers to disperse and “stop annoying His Royal Highness.” It was too late for such high-handed words. The rebels immediately chopped down Douglas, decapitated British Commissioner Simon Fraser, and set about killing any other European men, women, or children they could find. One of the first victims was the manager of the Delhi and London Bank who, along with everyone in his family, had his throat cut. Fifty other Europeans were tied together and slaughtered en masse by the king’s servants.

”All the Bungalows are Being Burnt Down by the Sepoys From Meerut!”

There were no all-British regiments in Delhi, and the sepoys in the Delhi garrison killed their officers and joined the mutineers. The officers who weren’t killed made their way, along with any terror-stricken civilians who had escaped the killing, to Delhi Ridge overlooking the city, where they set up a stronghold. Meanwhile, nine other officers were killed blowing up the garrison’s main powder magazine and arsenal. Inside Delhi, some of the company managed to escape with the help of their faithful servants and a few loyal sepoys, but most were cut down where they stood. The city’s telegraph operator managed to get off a last alarming message from the scene: “We must leave office. All the bungalows are being burnt down by the sepoys from Meerut. They came in this morning. We are off.”

As the situation worsened, thousands of mutineers poured into Delhi. A form of civil administration was set up, with the king acting as head of a ruling council, but it was all a sham. Bahadur Shah’s sons and grandson were the real powers behind the throne. Meanwhile, widespread looting continued, European homes were stripped, and business came to a standstill in the formerly thriving community. Word of the Meerut mutiny spread throughout northwest India, and new mutinies sprang up at Aligarh, Gwalior, Jhansi, and Benares.

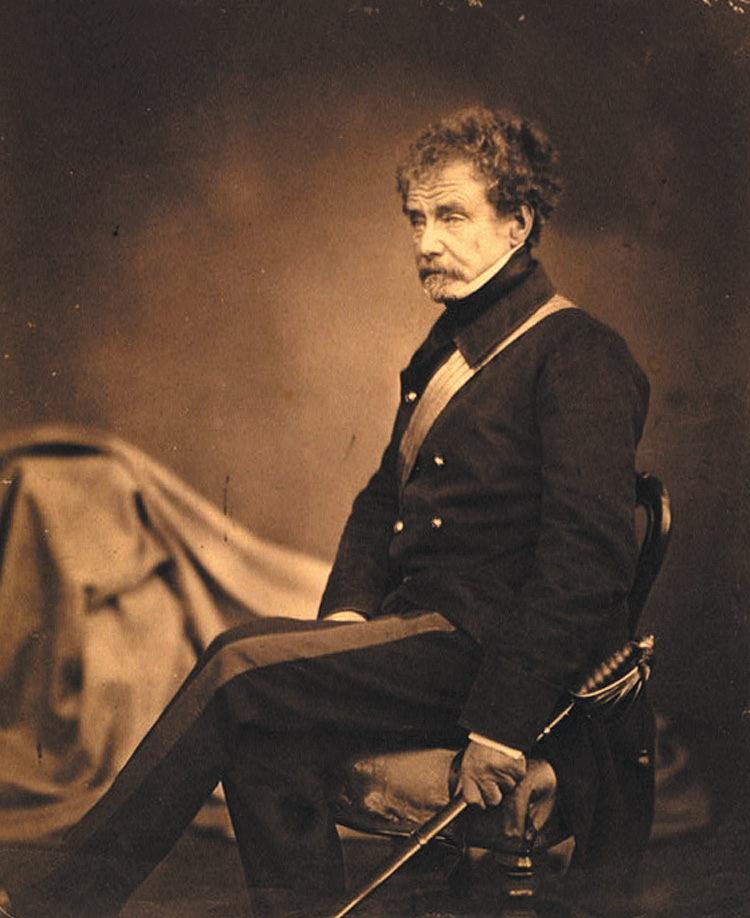

News of the Meerut uprising reached Cawnpore on May 14, but nothing happened there for another week. The garrison commander, General Sir Hugh Wheeler, was an old India hand. He had served on the subcontinent for half a century and had taken an Indian wife. Deciding not to disarm the sepoys serving under him since he felt this would send the wrong message, Wheeler instead fortified two hospital barracks on the edge of the cantonment for use as a refuge for members of the British community. The fortifications, two low earthworks surrounding the buildings, were more for show than effect, as were Wheeler’s ostentatiously unconcerned personal appearances in the compound, often in the company of his two daughters. After chatting with the sepoys on line, Wheeler reported that he had not found “anything like plotting in their midst.” Still, to be on the safe side, he permitted his senior artilley officer, Major George Larkins, to place a guard over the station’s guns.

In London, members of Queen Victoria’s government reacted slowly to the news that the Indian Rebellion of 1857 had officially begun. Prime Minister Henry Palmerston did not immediately grasp the seriousness of the situation; he assured the queen that things would turn out well. The queen, for her part, found the news “most distressing” and “the moment … certainly a critical one.” She chided her ministers, with some insight, for hastily demobilizing British troops after the conclusion of the Crimean War a year earlier. “If we had not reduced in such a hurry this spring,” said the queen, “we should now have all the men [we] wanted.” Eventually, a relief force of 40,000 soldiers was packed into ships for a three-month-long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to India.

Nana Sahib Sent 500 Men, 2 Elephants, and 2 Guns to Safeguard the Facility

In the meantime, the British nationals trapped in the seething countryside had to deal with an increasingly restive populace. At Cawnpore, General Wheeler was reassured by a visit from Nana Sahib, the maharajah of Bithur, a small town 10 miles away on the Ganges River. Nana Sahib nursed a grudge against the East India Company for not paying him a royal pension, which he thought was his due as the adopted son of the last Mahratta ruler. He considered himself the closest thing to an emperor the nation’s millions of Hindus had. Now, putting aside his grudges, he approached Wheeler with an offer to help in any way he could. Wheeler asked the maharajah to reinforce the sepoy guard at the treasury, some distance outside the cantonment. Nana Sahib immediately complied, sending 500 men, two elephants, and two guns to safeguard the facility.

On June 3, Wheeler’s informants warned him that an uprising was imminent at Cawnpore, and the general ordered all women, children, and noncombatants to take shelter in the fortified compound. That same day, an evil augury reached the cantonment, when the slaughtered bodies of a European man and woman floated down the Ganges and snagged in the locks of the Cawnpore canal. Two days later, at 1:30 in the morning, three pistol shots rang out, signaling the start of the uprising at Cawnpore. The sepoys in the 53rd and 56th Native Infantry led the way, setting fire to tents and bungalows and making straight for the treasury, where Nana Sahib’s soldiers obligingly stood aside while they looted it. The rioters then broke into a nearby magazine, released convicts from the town jail, set fire to the public records office, and set out on the Grand Trunk Road bound for Delhi. Less than 20 miles down the road, however, the rioters turned back to Cawnpore and placed themselves under the personal command of Nana Sahib.

It isn’t known definitively whether Nana Sahib was in league with the mutineers from the beginning, whether he was impressed into their cause after the fact, or whether he incited them to riot, but whatever the truth, he now took command of the mutiny at Cawnpore. He sent Wheeler a terse letter warning that he was about to attack, and the siege of Cawnpore began in earnest on June 6 with a bombardment of the hospital barracks where the European civilians had taken refuge. The barracks, two single-story buildings with verandas open to the flat ground, were about a mile from the Ganges. A thousand people sheltered inside the earthworks surrounding the buildings, including 300 women and children. The mutineers began a constant fire of muskets and artillery, which they kept up night and day for the next 18 days.

“The Sufferings of the Women and Children From Thirst Were Intense”

Conditions inside the shelter were hellish. Rebel snipers picked off unwary soldiers and civilians by the score, often before the very eyes of their loved ones. District magistrate Charles Hillersdon was disemboweled by a cannonball while standing with his wife, Lydia, on the barracks veranda. Mrs. Hillerson, who had just given birth to a new baby, watched in horror as her husband crumpled to the ground “in a heap of his own entrails.” Two days later, she joined him in death after another cannonball buried her under an avalanche of bricks, crushing her skull.

The fire was unremitting, as were the stifling midsummer heat and nerve-wracking wails of the hitherto pampered women and children. Provisions quickly ran out, and the only source of water was two wells several hundred feet from the barracks. Men braved the constant fire to lug back half-filled buckets of water, only to have other soldiers wrestle them away as soon as they returned. “The sufferings of the women and children from thirst were intense,” wrote Lieutenant Mowbray Thomson, “and the men could scarcely endure the cries for drink which were almost perpetual from the poor little babes, terribly unconscious … of the great, great cost at which only it could be procurred.”

Under the remorseless sun, the sniper fire, and the screams, even the strongest and most experienced soldiers began to crack. Many, including 56th Regiment commander Lt. Col. Stephen Williams, died of apoplexy, whose symptoms included “headache and drowsiness, followed by vomiting and gradual insensibility, which terminated in death.” So many dead bodies were strewn about the compound that, for reasons of hygiene, they had to be dumped into one of the two precious wells—no one could receive a proper burial. At that, the apoplexy victims were more fortunate than the isolated soldiers and civilians who were caught by the rebels outside the walls of the entrenchment. These victims, women as well as men, were mercilessly hacked to pieces, their heads carried in baskets to Nana Sahib, who received them as his royal due. Not even little children were spared. One English spy later reported seeing a woman and her children brought before the rebel leader. “Eventually their hands were tied,” the spy reported, “they were taken to the middle of the maidan and fired on, all were killed at the first volley except the infant. It was rolling about on the dead bodies and taking the hands of the corpses, was lifting them up and was saying, ‘Why have you fallen down in the sun?’ At last a trooper killed it with his sword.”

Two weeks after the siege began, the entrenchment was filled with half-starved children, sick and wounded men and women, and blind, insane, or helplessly apathetic individuals who could not even raise their heads to look outside. On June 25 a letter was brought to General Wheeler. Addressed to “the subjects of her most gracious majesty, Queen Victoria,” the letter offered the garrison survivors safe passage 100 miles down the Ganges River to Allahabad, which was still under British control. The letter, which was unsigned, was obviously was from Nana Sahib. After heated consultations with his officers and high-ranking civilians, Wheeler accepted, on condition that his soldiers be allowed to keep their sidearms and 60 rounds of ammunition.

”Many a Little Child was Raving Mad”

Two days later, at dawn, the evacuation began, with the sick and wounded being carried down to the Ganges in carts. The walking wounded followed, trailed by Wheeler and the rest of his men. “Never, surely, was there such an emaciated, ghostly party of human beings as we,” wrote Thomson. Another member of the party, 17-year-old Amy Horne, recalled that “the old—battered and bruised, like ships that come into port after being buffeted by storms—babbled like children; others had a vacant stare in their eyes, as if they beheld visions of the future. Many a little child was raving mad, and it was pitiful to see their singular behavior.” They reached the river at the village of Sati Chowra. The water was at a midsummer low point; heaps of wood, sodden vegetation and the occasional cadaver bumped against the banks. Twenty-four bamboo boats, 30 feet long and 10 feet wide, were pulled up to shore for the boarding parties. The fittest men among them waded into the river carrying the women and children, the sick and wounded, and loaded them into the boats. The native boatmen watched silently, as did dozens of mutineers lining both banks of the river. When the majority of the British had climbed aboard, the boatmen suddenly jumped overboard and thrashed ashore. Shouting for them to return to the boats, the British opened fire with their sidearms. Simultaneously, the mutineers on the riverbanks began shooting back with muskets and cannon loaded with grapeshot.

More and more sepoys poured from their hiding places in the village and unloosed a withering fire on the people in the boats. Coal embers secreted in the thatched roofs of the vessels ignited as well, immolating the clothes and bedding of the sick and wounded lying in the hulls. As the boats began to sink, the dazed survivors scrambled over the sides and either struggled blindly toward shore or cringed behind the smoldering wrecks in the shallow water. Bodies quickly littered the river, and women crouched down in the bloody water in a vain attempt to save themselves and their children. Babies floated downstream. Some of the men tried to push the boats into midstream to get away, but Indian cavalrymen rode their horses into the river, slashing with their sabers at the dwindling number of survivors. Only one boat escaped, rudderless and oarless, with two English officers and two Irish privates on board to tell the tale.

Neill and His Forces had Killed Nearly 6,000 Indians

Within an hour the killing was done, and all the British men were dead. An estimated 120 women and children were spared immediate death and imprisoned at Nana Sahib’s headquarters. Three days later, the rebels brought in General Wheeler and a handful of other officers and wives who had managed to drift downstream for 18 miles to the village of Sheorajpur, where they were becalmed and surrounded. Nana Sahib ordered a squad of sepoys from the 1st Native Infantry to shoot down the captives. “We will not shoot Wheeler sahib, who has made the name of our regiment great, and whose son is our quartermaster,” one sepoy protested. They asked Nana Sahib to put the men in prison instead. Other sepoys, from the Oudh Irregulars, protested vehemently, demanding to “kill them all.” The Oudhs got their way. Wheeler and the others were forced to kneel, and the Irregulars killed them with a blast of rifle fire and a flourish of swords for the coup de grâce.

Even as Wheeler and his doomed command were meeting their fates at Cawnpore, a British relief column led by Brig. Gen. Sir Henry Havelock arrived at Allahabad. The kilt-wearing 78th Highlanders had been preceded into town by Colonel James Neill and his punitive-minded party of 1st Madras Fusiliers, who had cut a wide swath of bloody retribution across the countryside from Benares to Allahabad. By the time Havelock arrived and put an end to the orgy of revenge killings, Neill and his combined force of British, European, and Sikh troops had shot, stabbed, burned, or hanged nearly 6,000 Indians. “They caught all the men on whom they could lay their hands,” wrote native traveler Bholanauth Chunder, “and hurrying them on through a mock trial, made them dangle on the nearest tree. For three months dead-carts daily go their rounds from sunrise to sunset, to take down the corpses which hung at the crossroads and marketplaces, poisoning the air of the city, and to throw their loathesome burdens into the Ganges.”

Havelock’s relief column headed for Cawnpore on July 7, unaware that they were already 10 days too late. Fighting off repeated attacks by Nana Sahib’s rebels, the column reached Cawnpore nine days later. The night before their arrival had seen another horror: The British women and children captured after the massacre at Sati Chowra had been mercilessly executed by the rebels. Those not killed by volleys of rifle fire had been chopped to pieces by a specially assembled execution squad of five sword-wielding rebels led by an embittered half-caste named Sarvur Khan, the son of a camp-following Pathan prostitute. Remembering his own destitute childhood, Khan harbored a special loathing for British women and children. With grim ruthlessness he and his comrades pushed their way into the compound where the sick, wounded, and dying prisoners lay, and for nearly an hour they proceeded to chop, hack, and stab their victims to death. Desperate mothers attempted to shield their children with their own bodies, or herded the screaming youngsters into the corners of the building, but there was no escape. When Khan and his henchmen emerged from the compound, soaked in blood, they left behind 73 slaughtered women and 103 children. Horrified onlookers ran away from the murderers, who calmly returned home to bathe.

Remember Crawnpore!

Nana Sahib and the rebel army fled westward as Havelock’s troops approached Cawnpore. An advance guard led by Lieutenant Richard McCrae entered the abandoned city the next morning. Dismounting his horse, McCrae shouldered open the door to the ruined compound. Inside he beheld the full horror of the previous day’s slaughter. The walls were splashed with blood; tiny handprints climbed the walls. A sticky coating of blood covered the floor, and battered ladies’ bonnets and sun hats lay scattered about, along with torn pieces of clothing, children’s shoes, and long tresses of chopped-off hair. Outside, the soldiers discovered the burial well used first by Wheeler’s besieged force, now choked to overflowing with the sundered bodies of women and children.

“Remember Cawnpore” immediately became the battle cry of the British troops, and the very word “Cawnpore” was used to justify an appallingly brutal retribution against Indian nationals. Captain (later Field Marshal) Garnet Wolseley, who saw firsthand the compound at Cawnpore, remembered years later: “A more sickening, a more maddening sight no Englishman has ever looked upon. Upon entering the bloodstained rooms, the heart seemed to stop. The horror of the scene was appalling and called up our worst angry passions. It awoke in us, the countrymen of these helpless victims, a fiendish craving for the blood of the cowardly murders. The idea that a native should have dared to put his hands upon an Englishman was too much. An all-absorbing craving for ruthless vengeance, that most unchristian of passions, was deep in our hearts, but had any English bishop visited that scene of butchery when I saw it, I verily believe that he would have buckled on a sword.”

The furious British soldiers at Cawnpore rounded up all suspected mutineers, subjecting them to deliberate degradation before flogging and hanging them from hastily improvised gallows. Hindu captives were forced to eat beef, and Muslims were forced to eat pork—those who refused simply had the offensive meat stuffed down their throats. The British forced other prisoners to lick up the blood from the compound floor where the helpless women and children had been slaughtered, and high-caste Brahmins were executed by low-caste street sweepers, whose merest touch was supposed to send the Brahmins into a series of hideous reincarnations as snakes and toads. Still other prisoners were tied to the mouths of cannon and blown to pieces. Supposedly, this was a relatively painless form of death, but American Methodist missionary William Butler said it was intended mainly to further humiliate the Hindu rebels, who believed that “the dissipation of the mortal remains of a man thus executed would necessarily … expose the disembodied ghost … to a wandering, indefinite condition in the other world, which they regard as dreadful.”

”Let Every Man Die at His Post; but Never Make Terms.”

Leaving the newly promoted Neill to garrison Cawnpore, Havelock marched to the relief of another besieged city whose name would become engraved in imperial memory. Lucknow, capital of the Indian state of Oudh, had been annexed the year before, and it was filled with angry dissidents. British Chief Commissioner Sir Henry Lawrence, commander of both the military forces and civil government at Lucknow, had anticipated trouble even before the mutiny began. Presciently, he concentrated the entire English community into a 33-acre complex of buildings in the residency compound. Lawrence then turned the compound into a fortress of trenches, palisades, booby traps, and wire entanglements to protect the 3,100 people surrounded there by 50,000 rebels. Lawrence himself was an early victim of the siege, mortally wounded by an artillery shell that shattered his thigh and caused him to bleed to death slowly over a two-day period. With Cawnpore’s fate still fresh in his mind, the dying commissioner gave a last peremptory order to his subordinates. “No surrender,” he commanded. “Let every man die at his post; but never make terms. God help the women and children.”

Bedeviled by repeated rebel attacks, heatstroke, and cholera, it took Havelock’s column two months to reach Lucknow. In the meantime, the British compound inside the city suffered many of the same hardships as their doomed countrymen at Cawnpore. The heat was ferocious, the rebel bombardment continuous, and snipers in houses and on rooftops outside the residency made any movement hazardous. The rebels began tunneling under the ramparts and setting off mines inside the compound. Luckily for the defenders, their own force included members of the 32nd Regiment from Cornwall, which contained several former coal miners. Together with loyal Sikhs, they counter tunneled and countermined the rebels; muffled explosions repeatedly shook the British defenses. Meanwhile, all the compound buildings were wrecked, food supplies dwindled precariously, and the air reeked with gunpowder and dead bodies. The women and children huddled together in cellars, plagued by large and rapacious rats.

Finally, on September 23, after 90 days of siege, the distant sound of gunfire and bagpipes was heard outside the city, and two days later a column of 1,000 bloodthirsty Highlanders led by Havelock burst into the residency compound. Close behind them were thousands of angry rebels. It was immediately obvious to everyone that Havelock’s force was not strong enough to break the siege on its own, and the would-be rescuers simply added their own numbers to the starvation and disease rife within the compound.

After another 53 days of siege, British Lt. Gen. Sir Colin Campbell approached Lucknow from the north. Inside the residency, 36-year-old Post Office employee Thomas Henry Kavanagh volunteered to disguise himself as an Indian and guide Campbell’s forces through the bewildering maze of city streets to the compound. (For his efforts, Kavanagh became the first civilian ever awarded the Victoria Cross.) Campbell’s relief force hammered its way past the rebel stronghold at Secundra Bagh, spearheaded by the 93rd Highlanders, 9th Lancers, elements of Punjab cavalry, sailors of the Naval Brigade, and Lieutenant William Hodson’s Irregular Native Horse. Arriving at the door of the residency on the night of November 17, Campbell immediately began organizing an orderly withdrawal of the compound’s survivors. The next night, screened by soldiers and under constant fire from the enraged rebels, the civilian women and children were brought out first, some in wagons, some in litters, the rest walking with their children held tightly in their arms. At midnight the remainder of the survivors, followed by a rearguard from the 93rd Highlanders, left the burning ruins of the residency. The six-mile-long procession made its way to Cawnpore and then to Allahabad.

The Mutiny Cost the Lives of 13,000 Soldiers, 40,000 Mutineers, and Thousands of Civilians

Campbell left behind a token force of some 4,000 men and 35 guns, which took up positions in a fortified garden south of the city at Alum Bagh. The force was both promise and warning to the rebels inside Lucknow that Campbell would return and deal with them later. Among those left at Alum Bagh was General Havelock, newly knighted and promoted to major general for his efforts at Cawnpore and Lucknow. Havelock did not have long to enjoy his new titles. Gravely ill with dysentery, he died on November 24. To his son and aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Harry Havelock, he spoke his last words. “Harry,” he said, “see how a Christian can die.”

With the relief of Lucknow, the British Army began steadily reoccupying northern India, sweeping across the country in rampaging columns to avenge the murder of innocent noncombatants at Cawnpore and elsewhere. An organized frenzy of shooting, looting, burning, and hanging continued through the summer of 1859, long after the mutiny itself had been put down. The Indians named this thirst for revenge, with some accuracy, “the Devil’s Wind.” Much to the ongoing frustration of the British, the one man they would have liked most to capture, Nana Sahib, “the butcher of Bithur,” managed to escape into Tibet, where he died in obscure circumstances a few years later. Madame Tussaud’s famous wax museum included an effigy of Nana Sahib, “clothed in the winter costume of his country … despised and forsaken,” until it was quietly removed in 1878.

In the end, the Indian Rebellion of 1857 cost the lives of at least 13,000 British and allied soldiers, 40,000 mutineers, and an untold number of British and Indian civilians. It also took the life of the East India Company itself, whose 258-year raj came to end on November 1, 1858, when Queen Victoria issued a formal proclamation resolving “to take upon ourselves the government of the territories of India heretofore administered in trust for us by the Hon. East India Company.” From then on, for better or worse, the Crown ruled India.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments