By Eric Niderost

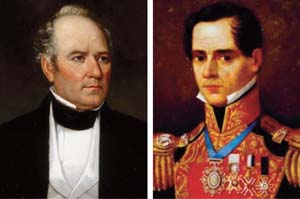

On March 11, 1836, General Sam Houston rode into Gonzales, a small town near the Guadalupe River in Texas. He brought momentous news: a convention had gathered at Washington on the Brazos River, and after much debate, some of it acrimonious, declared Texas an independent republic from Mexico. But Houston was no mere messenger; his main task was to marshal forces for the defense of the fledgling state.

Houston knew his task was not going to be easy, but he soldiered on, both literally and figuratively. Still, what he saw in Gonzales must have been sobering. “I very soon discovered that I was a general without an army serving under a pretended government that had no head, and no loyal subjects to obey its commands,” he said.

When he arrived he found 374 men waiting for him, raw militia, some of whom had never fired a shot in anger. They lacked food, and some of them lacked arms and ammunition. But their greatest flaw was their total lack of training and discipline, the two pillars of any effective fighting force. For the most part they were yeomen farmers with a sprinkling of frontiersmen, hunters, and all around ne’re do wells of a type that usually were drawn to wilderness areas.

This Texas Army was a sorry spectacle to Houston’s discerning eye. Some wore buckskins, black and greasy from long use and exposure to rain, while others wore farmer’s garb. A few so-called town types sported businessman’s attire, with a tail coat or frock coat over a shirt and vest.

Headgear was as varied as the individuals who wore it. “Here a broad brimmed sombrero overshadowed the military cap at its side; there a tall begum [top hat] rode familiarly beside a coonskin cap,” said Noah Smithwick, a member of the Texas Army.

But more troubling was their resistance to the most rudimentary forms of military discipline. They preferred to elect their officers, men who could be removed if they issued too many unpopular orders. As militia this rag-tag conglomeration was an imperfect instrument, but Houston was determined to avoid a fight until he felt they were ready to take on the Mexican Army.

When Houston arrived all minds were focused on the unfolding drama taking place some 50 miles away at San Antonio. A rebel garrison of fewer than 200 men found itself under siege in an old mission that had been converted into a makeshift fort. The mission was the Alamo, now enshrined as a legendary landmark of American history. The Alamo was surrounded by a large Mexican army under the personal command of Mexico’s dictator, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna y Perez, and it was not known how long it could hold out.

On March 11, the same day Houston arrived at Gonzales, word came about the fall of the Alamo. Andres Barcenas and Anselmo Bergaras were the bearers of these bad tidings, which Houston believed but needed confirmed before he could proceed further. As the news spread through the Texas Army some of the men began to show signs of real agitation. Houston knew he had to nip this panic in the bud, so he arrested the two men as spies for Santa Anna. They were later released, but the action had its desired effect, and the soldiers calmed down.

On March 13, Houston dispatched three men, including his best scout, Erasmus “Deaf” Smith, to the west to confirm the Alamo’s fall. Meanwhile, Houston made his first attempts to organize this amorphous mass of raw civilians into real soldiers. To begin with, some sort of organization was needed, so he created a 1st Texas Volunteer Regiment with Colonel Edward Burleson in command. As the army swelled with new recruits, a second regiment would be formed.

Houston’s scouts came back a few hours after they departed, bearing evil tidings. Smith and his companions came upon a dispirited and very weary band of Alamo survivors. The party included Susanna Dickenson and her infant daughter Angelina and the late Lt. Col. William B. Travis’s slave Joe. They recounted the Alamo’s last moments in chilling and graphic detail.

The survivors also carried a letter confirming the Alamo’s fall, written in English by Santa Anna’s aide, Juan Almonte. The news was not just bad, it was devastating, especially to the residents of a small town like Gonzales. No fewer than 32 Gonzales men had answered Travis’s plea for help, and now all were dead. In one stroke 27 women were widows and approximately 100 children lost fathers.

The resulting scenes in the streets of the little town were horrid. Cries and lamentations filled the air, and the weeping was so heart rending even the toughest male observer was moved. Some of the women were almost hysterical with grief, and Houston did what he could for them. Wagon transportation was arranged for the Gonzales families so they could accompany the Texas Army.

The news was like a stone dropping into a pond, spreading ripples of fear and consternation through the ranks. Around 25 men deserted, obliquely proving Houston’s point: The Army of Texas was more apparent than real. It needed training and discipline if it ever hoped to win a victory over Santa Anna. No doubt a few deserters succumbed to fear, but there was another, even more compelling, reason to decamp: the safety of their families. Many probably left to make sure their loved ones would be out of harm’s way.

But it seems the bulk of the Texas Army wanted to fight, and fight as soon as possible. Seething with anger, they wanted to avenge those compatriots who had been so ruthlessly slaughtered. Their righteous anger was augmented by a kind of cocksure quality that many Americans had at the time.

In the 1820s, Texas was a frontier outpost with a few thousand Hispanics living in a handful of missions and isolated settlements. These Spanish-speaking Mexican Texans, or Tejanos, faced two threats: annihilation by hostile tribes like the rampaging Comanche or political takeover by Americans who might flood over the unprotected border.

The Mexican government decided to allow immigration from the United States but would require the newcomers to become loyal Mexican citizens. If these Anglos would also agree to learn Spanish and become Catholics, at least on paper, they would be rewarded with generous grants of fertile land.

Stephen Austin, an American who spoke Spanish and genuinely respected Hispanic culture, was made empresario, a kind of land baron or developer who would screen and settle prospective applicants. These early American Texicans were also to form a kind of buffer between the Hispanic settlements and the hostile Indian tribes. Austin’s settlement of 300 families, which was dubbed the Old 300, was an immediate success, and on the whole the two disparate peoples, the Tejanos and Texicans, got along well.

But the Mexican government grew alarmed when it realized the “Texians” were vastly outnumbering the Tejanos. There were approximately 4,000 Hispanics and 35,000 Americans residing there by 1835. The Mexican government tried to slow further U.S. immigration. It was already too late because a whole section of southeastern Texas was being rapidly Americanized.

The Texas Revolution broke out in late 1835. A new dictator, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, tried to establish an authoritarian government in Mexico. As a result, Anglos and Tejanos rose up and expelled Mexican forces from Texas.

Texas settlers, seemingly triumphant, began to drift back to their farms. But anyone who underestimated Santa Anna did so at their peril. Even before Mexican troops were defeated, Santa Anna was forming plans to raise an army and deal with these Norteamericano interlopers personally. He led a 6,000-man army into Texas, surprising all by conducting an almost unheard of winter campaign. The Alamo was put under siege, and on March 6, 1836, taken by storm.

Thus, Houston found himself in a predicament that would have taxed even a Caesar or Napoleon. He was in personal command of approximately 300 men at Gonzales, on paper the main army of the newly fledged republic. There were also isolated units scattered all over the length and breadth of Texas, formations that were supposed to rally to Houston at the earliest opportunity. James Walker Fannin had the largest group, some 400 men, around 125 miles away at Goliad. Even before the fall of the Alamo was confirmed, Houston sent Fannin a message ordering him to join the Gonzales army at once. Houston confided in Fannin, telling him he feared the mission fortress was indeed lost.

Fannin had attended West Point but had dropped out well before graduation. It was obvious most of the military academy’s training failed to make much of an impression on him. Even though bad luck played a role, most of Fannin’s impending tragedy was his own doing. As a soldier he was brave enough, but also cursed with a fatal indecisive streak that would ultimately doom him and his men.

Fannin could not make up his mind about retreating, at first ordering a withdrawal, then canceling that order. In the end, Fannin and his men were caught in the open by Mexican cavalry under General Juan Jose Urrea. Harassed by Mexican fire and tortured by a burning sun, Fannin’s men suffered terribly from thirst. Fannin finally surrendered “at discretion,” meaning he threw himself on the mercy of Santa Anna.

Urrea, an honorable soldier, almost certainly was sincere in his conviction that the prisoners would be well treated. He was wrong. Santa Anna wanted to erase the American presence in Texas by executing all insurgents that fell into his hands. On Palm Sunday, March 27, 1836, 342 prisoners were marched out and shot. A handful managed to escape or were hidden by sympathetic Mexicans. Fannin himself was shot in the head, paying the price for his inept leadership.

Santa Anna’s Army of Operations had been bloodied at the Alamo. Casualty figures are disputed, and even today are subject to fierce debate. Historians estimate losses at upward of 300 killed. The figure includes wounded who subsequently died, because Santa Anna did not bother to bring any medical staff. But it did not matter much to the dictator, who once said, “What are the lives of soldiers than so many chickens?”

With his cavalier attitude toward human life, whether his men or the enemy, Santa Anna was not much impressed by the insurgent resistance. Fannin’s bungling and subsequent surrender seemed to confirm Santa Anna’s low opinion of these seemingly incompetent Americanos and their Tejano allies. The general even briefly considered returning to Mexico, but allowed his underlings to persuade him to stay.

The dictator divided his army, sending units across the length and breadth of Texas. The First Brigade under General Antonio Gaona was ordered to sweep northwest, harrying the rebels from San Antonio to the Colorado River. Urrea, his Fannin-Goliad mission accomplished, was to advance along the coast, taking on any Texans he might encounter. Santa Anna and the main army headed for Gonzales, where Houston and the main Texas Army was located. The vanguard of the Mexican Army, which was led by General Joaquin Ramirez y Sesma, would soon reach Gonzales. If Ramirez y Sesma could catch Houston, he might be able to harry him until Santa Anna’s main body arrived.

In the meantime, Houston had decided on a full-scale retreat. He needed to buy some precious time to train his men into some semblance of a real army. There were other considerations as well. Gonzales was on the border of Hispanic Texas, and it made sense to pull back into Anglo settlement territory to the east. There were a number of rivers there that could be used for defense, and Anglo Texas might yield hundreds more recruits.

This is not to say the Texas Army shunned Hispanic help. Captain Juan Nepomunceno Seguin was a Tejano who joined the revolutionary cause. Eight Tejanos were among the men who fell at the Alamo. Seguin formed a Tejano company that performed vital duties for Houston and the revolution. They scouted for the Texas Army, protected outlying ranches from Indian attacks and, most importantly, escorted fleeing Anglo families from Mexican cavalry patrols.

The retreat began in the predawn hours of March 14, 1836. Houston was moved by the plight of the Gonzales residents, particularly the grieving widows and their families. So he burned some army baggage to free up wagons to be used for their transport. Houston adopted a scorched earth policy; nothing would be left for the enemy. Gonzales residents would accompany the army, and their town would be put to the torch.

The army trudged along, and since it was still nighttime, they were enveloped in a pitch-black darkness that matched their depressed mood. They soon entered a thick oak forest that made it even darker. The only light was several miles to the rear, where a burning Gonzales cast a strange yellow-orange glow in the sky. After a brief rest, Houston decided to continue on to Burham’s Ferry on the Colorado River, a waterway not to be confused with the more famous stream that flows through the Grand Canyon.

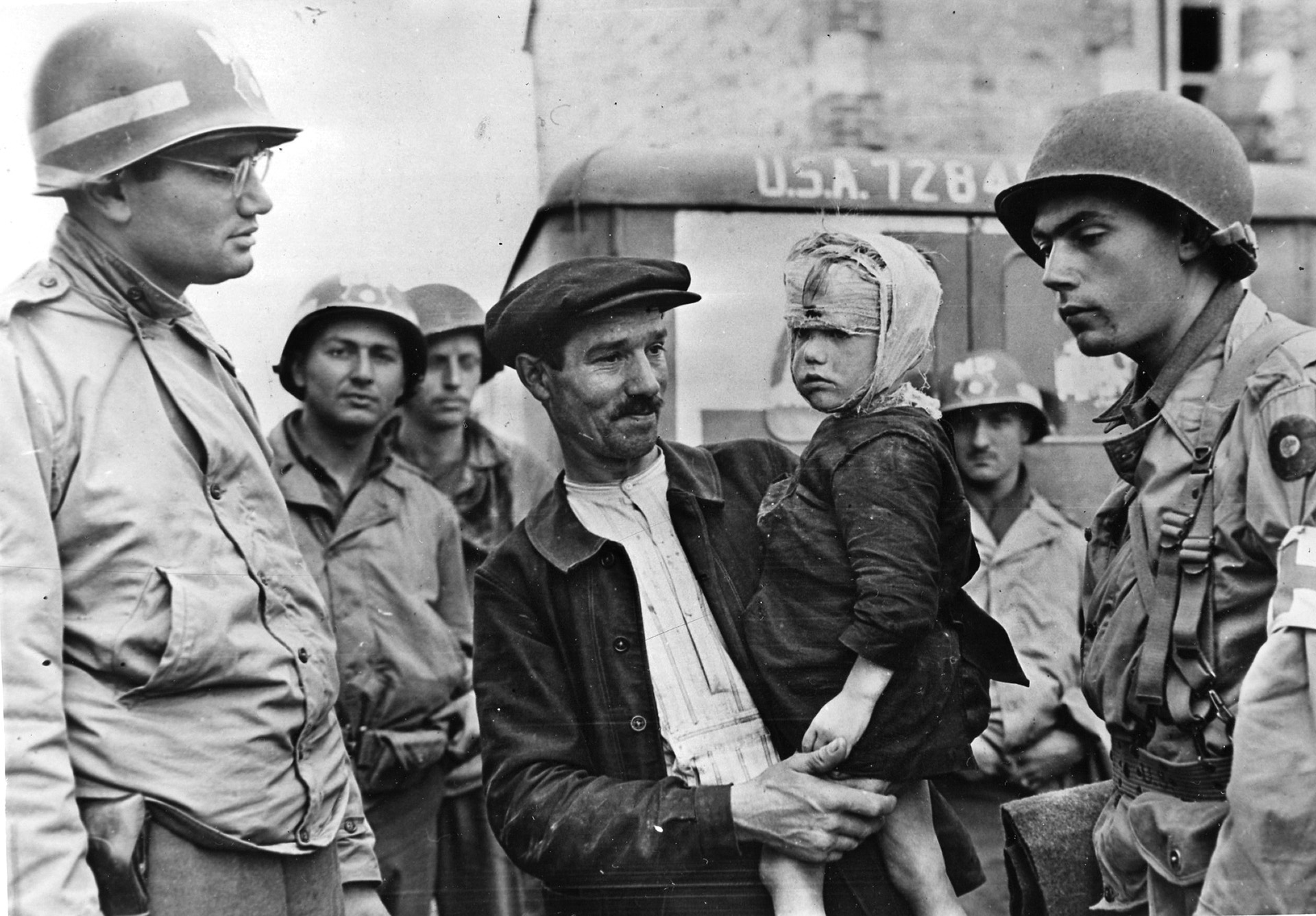

In the meantime, the advances made by the Mexican Army caused thousands of Anglo-Texans to flee, a mass exodus known to history as the “runaway scrape.” It was the rainy season in Texas, and intermittent rains made the rude unpaved roads muddy quagmires. Long columns of Anglo Texans, mainly women and children because their men were joining the army, trekked through the viscous muck trying to stay ahead of Santa Anna’s victorious legions.

The refugees grew exhausted and, with food scarce hunger weakened bodies and made them more susceptible to disease. Fevers spread, there were outbreaks of measles, and people started to die. One refugee recalled that 5,000 people were desperately trying to cross the San Jacinto River at Lynch’s Ferry. All along the refugee trails, a shout of “the Mexicans are coming” was liable to start a stampede.

The Texas Army reached Burham’s Ferry on March 17 and quickly made camp. The next day a drizzly, clammy rain returned, turning their bivouac into a sea of mud. The following day the army crossed the Colorado, putting the river’s wide, deep, and swift waters between them and the approaching Mexicans. Runaway scrape refugees were also helped across, and when the last person was safely on the eastern bank, the ferry was destroyed.

General Ramirez y Sesma, in hot pursuit, caught up with Houston a few miles downriver from Burham’s Ferry. Unfortunately for the Mexicans, the Colorado River was between them, serving in effect as a moat that protected the Texans. Houston allowed a small group to have a brief skirmish with Ramirez y Sesma to take the edge off their hunger for combat, but would allow no major engagement.

After a brief stop to burn San Felipe de Austin, the old capital of the original Anglo settlement, the march continued until it reached Groce’s Crossing on the Brazos. From March 31 to April 13 the army stayed in camp, drilling under Houston’s careful and demanding eye. More men came in, and Houston was pleased to receive two cannons, gifts from the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, that were quickly dubbed the Two Sisters.

At the time the boundary between Mexican Texas and the United States was the Sabine River. There is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that Houston, if all else failed, planned to retreat as far as the Sabine. Santa Anna’s line of supply and communication, already overextended, would be stretched to the breaking point. But there was another consideration: clandestine help from the United States. At that moment General Edmund Pendleton Gaines was on the border, leading a U.S. Army of Observation. Yet Houston was an opportunist; he was going to attack if he felt his men were ready, and if Santa Anna made a mistake large enough to exploit. He was not going to arbitrarily stick to some secret plan at all costs.

Houston’s army was bulked up by U.S. soldiers, troops who arrived in full uniform and kit. They were strictly unofficial; however, they were deserters who had skipped out when Gaines was not looking. That, at least, was the cover story, and Houston formed them into a regiment of regulars as opposed to a regiment of volunteers. Being for the most part fully armed, they were a welcome addition to the Texas Army.

Then Santa Anna made a mistake, and it was an error the magnitude of which was going to cost him the war. Impatient at what he considered more of a farce than a military campaign, he decided to try and capture the rebel interim Texas government. The dictator managed to cross the Brazos by trickery, something that even Houston had not thought he could do. Colonel Juan Almonte, who again spoke perfect English, hailed an unsuspecting black ferryman and asked him to bring his barge to the west bank. Once the ferry crossed over, Mexican soldiers jumped out of the bushes and secured the vessel.

Once his army was ferried over the Brazos, Santa Anna hurried on to Harrisburg, on Galveston Bay, where the Texas interim government was sheltering. They learned of the Mexican approach in the nick of time, with literally minutes to spare.

His surprise coup almost succeeded. President David Burnett and his cabinet had taken a boat to row to Galveston Island. They had pulled away minutes before and were still so close that arriving Mexican cavalry could have opened fire across the water. Colonel Almonte, seeing Mrs. Burnett in the boat, chivalrously declined to shoot. But in his haste to round up the rebels, Santa Anna had forged ahead with only 700 men. That made him vulnerable to a possible Texas counterstroke.

Once he heard that Santa Anna had crossed the Brazos, Houston knew the Texas Army must follow. Luckily he had secured the services of the Yellow Stone,a 130-foot, 144-ton steamboat. Captain John E. Ross was ready, willing, and able to serve the cause of Texas independence. “I have four cords wood on board and everything ready to go ahead,” he assured Houston.

A plan was forming in Houston’s mind. The trick was to make it seem that he and his men were cornered. Once that was achieved, the Texans would turn the tables on the Mexicans and spring a trap.

On April 18, Santa Anna arrived at New Washington, a town on the San Jacinto River. He was still far in advance of his army; General Vincente Filisola, an Italian in Mexican service and a Napoleonic War veteran, was with the main body at Fort Bend on the Brazos roughly 45 miles away.

At that point, Houston crossed Buffalo Bayou and took his men to the San Jacinto plain at a point where the river runs into the bayou. Scenting victory, Santa Anna burned New Washington to the ground and hurried to the plain. He did not want his quarry to escape again. On April 20, there was some half-hearted skirmishing, but it was a weak overture to the main act, which would take place on the next day.

Santa Anna actually had his buglers sound “Deguello,” the old tune that announced no quarter would be given to prisoners, a couple of times during the fray. It had been played at the Alamo, and Santa Anna’s gesture shows how out of touch he was in assessing the morale of the Texans. The shrill bugle notes were bound to enrage the Texas Army, reminding them of the slaughter at the Alamo and Goliad.

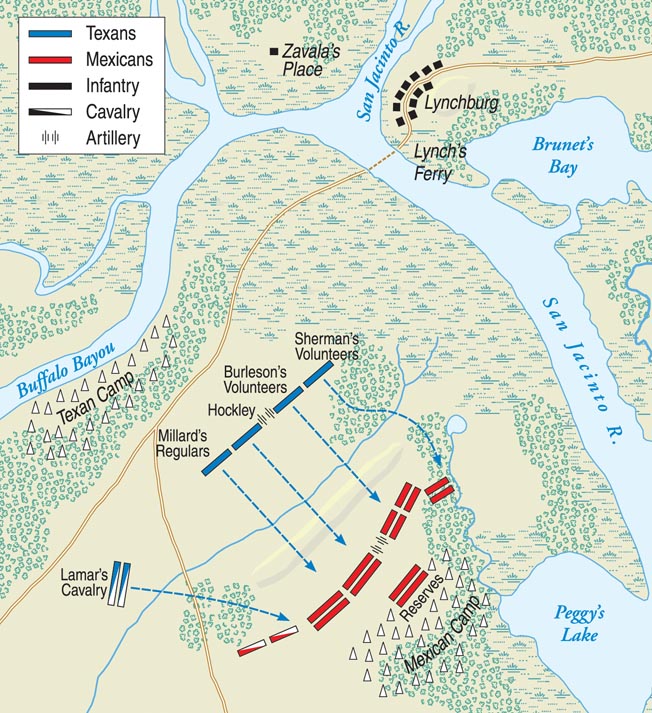

The future battlefield of San Jacinto was a small grassy expanse barely three square miles in area. The grassy plain is marshy along its edges, and here and there are stands of live oak and shallow ravines. The battlefield is bounded on the northeast and northwest by the San Jacinto River and Buffalo Bayou. Neither waterway is fordable, which meant the only means of escape in that area was by Lynch’s Ferry. Actually, no defeated army could really hope to shuttle back and forth to safety if it were pressed by a victorious enemy. There would be no time.

Santa Anna’s army bivouacked in the southwest corner of the San Jacinto plain. There was a small copse of live oak just in front of his position, but even the overconfident dictator realized that was not enough for defense. To flesh out the defenses he had his men throw up a makeshift, entirely slapdash line of pack saddles and various odds and ends. Several of his subordinates respectively objected to the position, but he arrogantly dismissed their valid fears.

The problem was simple: Santa Anna’s camp was up against a boggy swamp and a body of water called Peggy’s Lake. If something went wrong, and the Mexicans were forced to retire, they might be trapped. But again, Santa Anna dismissed such concerns. Indeed, the dictator’s brother-in-law, General Martin Perfecto de Cos, was marching to his aid with approximately 600 reinforcements. That would give Santa Anna some 1,200 men, more than enough, or so he thought, to deal with Houston and his rag tag upstarts.

The next day, April 21, 1836, was going to be the moment of decision. Yet, curiously, Houston did nothing for several hours, and indeed spent the morning in relative idleness. But there was method in his madness. If he launched an attack too early, he might be heavily engaged when Cos arrived. The sudden influx of new Mexican troops might panic his men to the extent they would be defeated. He diecided to wait for Cos and take on Santa Anna’s combined forces all at once.

General Cos did indeed arrive at mid-morning. Santa Anna, pleased to see his disgraced relative, ordered the newcomers to relax. Many of the soldiers slept, while others started fires and prepared food. The atmosphere was relaxed, even though Houston and the Texans were only about 500 yards away.

Santa Anna himself was resting in his large brown and white striped tent. Legend insists he was entertaining at least one female, a mulato woman named Emily. This Emily became enshrined in song and story as the Yellow Rose of Texas, but the tale is almost certainly apocryphal. Santa Anna might have been a womanizer back home in Mexico, but on this campaign he had more important things on his mind, like the utter extirpation of the American presence in Texas.

At approximately 3:30 pm Houston formed his men into two battle lines and ordered an advance. Standing 6 feet 2 inches, he was always imposing, but on occasions such as this he seemed truly magnificent. He had a powerful, muscular build and a ruggedly handsome face. His blue eyes could quickly become cold and steely if angered. Houston mounted his white stallion, Saracen, and placed himself at the front of his troops.

The Texas Army formed up on two lines stretching about 1,000 yards. The far left was occupied by Colonel Sydney Sherman’s 220-man Second Texas Regiment, followed by Colonel Edward Burleson’s First Texas, numbering 260 effectives. The First Texas had been organized weeks before, when Houston had formally taken command at Gonzales. Would Houston’s painfully difficult attempts to train them into something even remotely resembling soldiers bear fruit? Only time would tell.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Millard’s Texas Regular Battalion, many of whom were deserters from the U.S. Army, anchored the right. They came fully equipped for the most part, with Model 1816 muskets and formidable bayonets. Most if not all of them were clad in U.S. Army blue; there was no attempt to disguise their presence. There were also some 50 cavalrymen under a man with a romantic, swashbuckling name, Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar.

The Texas Army’s artillery support came from the two guns of the Cincinnati Battery, which were placed in the Texas Army’s center. The 31 men who worked the cannons became quite adept at both firing and moving the heavy metal monsters in their charge. At one point they even manhandled the Two Sisters to within 70 yards of the Mexican position.

Armies of the period often had regimental bands, and in battle lively airs helped maintain a martial spirit. Houston managed to gather a fifer and a drummer or two, but it was said the fifer’s musical repertoire was limited. He only knew, so the story goes, “Will You Come to the Bower?” The song, referring to a man who invites his lover to a romantic rendezvous, was considered erotic, or at least risqué, but any musical port would do in the coming storm.

Seguin and his Tejanos also were present. Seguin had only about 20 men, since most of his command was still away on detached duty. They put playing cards in their headbands, so Anglo Texans could recognize them as friends, not foes.

At Houston’s signal, the advance began. The Two Sisters roared out a twin salvo, ripping through the makeshift barrier that guarded the Mexican camp. It was a rude awakening for many of the Mexican soldiers, including Santa Anna himself, who had been fast asleep in his tent. A Mexican bugler near the Matamoros Battalion sounded the alert, his shrill notes of urgency reverberating through the camp, and soon other buglers joined in the swelling chorus of alarm. The clarion calls proved tardy and ultimately futile.

A few Matamoros Battalion soldiers fired at the advancing enemy, and a solitary Mexican cannon discharged some grapeshot with an ear-splitting roar. The Mexican fire was so hasty that most of it went over thr Texans’ heads.

General Manuel Fernandez Castrillon was one of those officers who kept his head. He was in the middle of shaving when the bugle calls, cannon fire, and musketry began echoing through the camp. Though only half dressed, he traded his razor for his sword and began shouting orders in rapid fire succession: the Aldama Battalion was to support the Matamoros, while the Guadalajara, Toluca, and Guerrero Battalions were to form up and launch counterattacks.

Literally caught napping, the whole Mexican camp dissolved into chaos. Officers tried to shout orders as sleepy-eyed soldiers stumbled about trying to make for their stands of weapons. These Mexican troops, like all trained soldiers of the period, were used to fighting by command in serried, ordered ranks. Fighting that required individual initiative or prowess was beyond them, and this was exactly the kind of barroom brawl in which the Texans excelled.

The formal fighting, if you could call it that, was over in 18 minutes. The Texas swarmed over the Mexican barricades like avenging furies, screaming “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” as they entered the Mexican camp. Castrillon, bleeding from a leg wound, climbed up on an ammunition box and tried to rally his men by shouting words of encouragement over the din. He was ignored, and the Mexican Army quickly dissolved into a band of panic-stricken fugitives

The Aldama Battalion managed to rally but its formation was broken up by fleeing soldiers from other units. Before they could reform they were engulfed by a tidal wave of rampaging Texans. By most accounts, Santa Anna ran around giving incoherent and contradictory orders, but soon took to his heels when he saw the game was up. Colonel Almonte, who was educated in the United States and spoke good English, managed to rally some men and take them to some swampy areas near the bayou. They managed to hold out until Texan passions cooled and were allowed to surrender honorably.

After the formal battle the slaughter began, which tarnished the subsequent victory. The weeks of frustration and retreat, combined with the pent up desire for revenge and the seething anger against Santa Anna, had created a volcano of emotion that finally erupted in the closing stages of the battle. The thin veneer of soldierly discipline, so carefully built up over the days, was shed within minutes.

Surrendering Mexican soldiers were ruthlessly cut down, with bowie knives slicing throats in crimson sprays of arterial blood, and axes and tomahawks chopping, rending, and cutting with brutal efficiency and similar gore. Even drummer boys were not spared. Houston, badly wounded in the ankle, still tried to control his raging soldiers. Unsuccessful, he finally rode off to get his wound dressed. “Gentlemen, I applaud your bravery, but damn your manners,” he said disgustedly as he departed.

The killing continued for hours; even those trying to seek refuge by swimming in Peggy’s Lake were shot down. A Texas officer named Rusk tried to save Castrillon, but the Mexican general was shot down anyway. The Texans, especially the rough frontier types, were not squeamish about taking human life and reveled in the violence. Eventually the blood lust abated and by sundown the Battle of San Jacinto was over.

When the battle began Houston had about 800 men, the Mexicans approximately 1,300. The casualty numbers are usually disputed, but seven to 11 Texans were killed and 30 wounded. The Mexican Army fared much worse, as might be expected. Approximately 600 soldiers were killed and 700 captured. It was a spectacular and one-sided victory.

But where was Santa Anna? Later he claimed he had gone to get help, or words to that effect, but it was plain he was saving his own skin. He hid out overnight, cold, hungry, and rightly fearing for his life. He was picked up by a Texan patrol, and since by most histories he had donned a private’s tunic, he was not initially recognized. Discovered at last, he was brought before Houston, who was still in great pain from a shattered ankle. It was said that Santa Anna’s feet were shod in Moroccan slippers, relics of that ill-fated nap he had taken the day before.

The two men conversed, and ultimately negotiated, through Colonel Almonte. Many Texas soldiers wanted to shoot or hang the defeated dictator on the spot, but Houston prevented a possible lynching. He knew that General Vincente Filisola and General Urrea were still a threat, and together they fielded around 4,000 soldiers. It was not very likely that the Texas Army could pull off another miracle win—Filisola and Urrea were far better soldiers than Santa Anna.

In the end, the best strategy was to use Santa Anna as a bargaining chip. He negotiated a deal by which the defeated dictator signed two agreements, one public and one private. The public agreement basically required the Mexican Army to restore any property taken, release any prisoners, and above all withdraw from Texas. The secret agreement stipulated that Santa Anna use all his influence to get Mexico to agree to Texas independence, with the Rio Grande as the boundary between the two nations.

These treaties were made on condition that Santa Anna’s life would be spared. Houston readily agreed to these terms because they served his immediate purpose: ending the war with Texas victorious. The pacts were illegal in that they were signed under duress, and in any case were never ratified by the Mexican congress. Indeed, the Mexican government as a whole repudiated the treaties immediately.

Nevertheless the whole course of western American history was changed in less than half an hour. Nine years later, Texas became a state, and Houston began his career as a U.S. senator. Santa Anna somehow survived what soon became a very rough captivity. At one point he was even put in heavy shackles, but eventually he was released. Santa Anna became Mexico’s bad penny, or perhaps, centavo, who would return to power in the 1840s and again in the 1850s.

I disagree with the remarks that the killing of the Mexican soldiers “tarnished” the victory. Santa Ana’s march from the Rio Grande was a punitive expedition and his army massacred many peoples and captured soldiers. He gave orders to give no quarter in his battles.

So the vengeance extracted at San Jacinto was due payback delivered.

Right you are, George. At the Alamo when the odds were 25 to 1 in his favor, Santa Anna ordered “no quarter”. When the last 7 Texians surrendered or at least stopped resisting, Santa Anna had the opportunity to show some small mercy. Instead, he showed contempt and indicated that his no quarter order still held. Those survivors were then set upon and hacked to death with swords in front of Santa Anna. With the fight a little fairer at SJ, the tables were turned and Santa Anna fled and hid like the coward he was.

The map of the battle area is great. It would be helpful, also, to have a map of the entirearea of the war to visualize the movements of the armies. Thanks.