By Frederick Grant

The siege of Poltava was not going well. It was June 17, 1709 and for six weeks an army under King Charles XII of Sweden had been besieging the fortress town near the Vorskla River in the Ukraine. Poltava was proving a tough nut to crack; its Russian garrison stubborn and courageous. The Swedes were veteran soldiers, accustomed to victory, and generally looked down on the Russians with ill-disguised contempt. Yet even Charles was forced to utter a few words of grudging praise when he said, “What! I believe the Russians are mad and will defend themselves in a regular way.”

[text_ad]

The summer heat grew almost unbearable, a stifling oven that drained a man of energy and left him drenched with sweat. The soaring temperature encouraged bacteria growth, and wounds festered. Soon, many wounded Swedes died when injuries putrefied with gangrene. Powder supplies were low, too, and much of what the Swedes had was damp. Lack of powder made the Swedish bombardment of Poltava sluggish at best.

Czar Peter I of Russia, later known as Peter the Great, was marshaling a large army just across the river in an effort to relieve Poltava and force a showdown with Charles. A major battle was in the offing: All signs pointed to it. Nothing less than the future of Russia was about to be decided on the banks of the Vorskla, a tributary of the mighty Dnieper.

The battle of Poltava was a phase in what became known as the Great Northern War, a conflict that was destined to last a whole generation, from 1700 to 1721. The roots of the conflict went deep, and centered around the shores of the Baltic, not the rivers of the Ukraine. In the late-17th and early-18th centuries the Baltic and its surrounding waters were basically a Swedish lake, and its shores part of a mighty Swedish empire.

Peter the Great’s Modernization of the Russian State

In 1700 Sweden was at the height of its power. Strong kings, subtle diplomacy, hard-fought victories, and brilliant generalship had carved out a Scandinavian empire like no other. But the Swedish empire was like a magnificent tree with a splendid trunk, thick branches … and very shallow roots. Sweden had only a million and a half people, a tiny population base for a great power. Contemporary France had about 20,000,000 people, for example, and Great Britain some 5,000,000 souls.

The Swedish empire was intact—but the winds of adversity were rising, and might prove strong enough to topple the mighty “tree.” To maintain both its empire and its great-power status, Sweden needed to be constantly vigilant. In a time when absolute monarchy reigned supreme, the issue of war and peace was bound up in the personalities of each respective ruler. The two dominant players of the Great Northern War were Peter of Russia and Charles of Sweden.

A towering figure in Russian history, Peter was also physically imposing. An astonishing 6-foot-7-, Russia’s ruler could be coarse and brutal, and his rages could make his court cringe with terror. He was a powerful man, muscular and lean, and hard manual labor only increased his brute strength. Peter was also afflicted with a facial tic, which under stress could develop into a full-blown convulsion. The left side of his head would jerk violently, his face contorted into a grim mask, and his eyes would roll up until the whites showed.

Apparently Peter was suffering from a form of epilepsy, but his intelligence was unimpaired. To Peter, Russia was backward, medieval and surrounded by powerful neighbors that looked on her with contempt. The only way Russia could take its rightful place among nations was to modernize—and to modernize, Russia would have to look west.

Peter took a trip to western Europe, and upon returning home he set to work, issuing a series of decrees that transformed Russia forever. Western technology was introduced, the coinage reformed, and the western Julian calendar made standard. The Russian year 7206 was now 1698. Since outward appearance can reflect inner thought and character, Peter saw to it that Russians adopted western European dress. Also, and most important, beginnings were made toward the creation of a Russian army on the western model.

In Pursuit of a Russian Sea Port

The Czar knew geography also influences the course of nations. In an era when the sea was an important avenue of trade, Russia was landlocked and lacked a seaport. The Turkish Ottoman Empire controlled the Black Sea, and was too powerful for Peter to dislodge. But what about the Baltic? Or more specifically, the Gulf of Finland?

The Swedish provinces of Ingria and Karelia bordered the gulf to the east and northeast, Swedish Finland to the north. Karelia and Ingria had been a bone of contention between different powers for centuries, a shuttlecock that bounced back and forth as fortunes waxed and waned. But these provinces had generally been Russian until Sweden had seized them early in the 17th century. Peter resolved to get them back.

Since Russia was landlocked, much of its trade flowed through the Swedish-controlled Baltic ports of Riga, Reval and Narva. The Swedes allowed their rivals to use the ports, but exacted a heavy “pound of flesh” in exorbitant tolls and duties. If Peter could regain the “lost” territory, however, he would have a seaport, which would be a conduit of trade and western influence.

Others cast covetous eyes on the Swedish empire; Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, was one of these. Sweden’s King Charles XI had recently died, and a 15-year-old Charles XII ascended the throne. Power politics knows no morality, and Augustus cynically suggested to Peter that Sweden’s Baltic territories could easily be wrested from the feeble grasp of a mere boy.

Peter was interested, but nothing more came of the matter. The tinder had been laid, however, and all that was needed was a few sparks to start the conflagration of war. The necessary spark was provided by John Patkul, a disaffected noble from the Swedish province of Livonia. Hoping for Livonian independence, or at least more autonomy for the nobility, Putkul persuaded Augustus to form an alliance with Frederick IV of Denmark and Peter of Russia. The object of this alliance was nothing less than the invasion of Sweden and the partition of its empire.

The Underestimated Charles XII

The Great Northern War began when Augustus invaded Swedish Livonia in February of 1700. There was no declaration of war, just open and unabashed aggression. Sweden’s position seemed hopeless; surrounded by enemies, the ship of state guided by an untried adolescent.

In truth, the young King of Sweden seemed a reckless boy, more interested in hunting and galloping wildly through the streets of Stockholm than in affairs of state. But there was more to Charles than met the eye. When he heard of the unprovoked invasion, the young king, now 18, took the news with a mature calm. “I have resolved never to begin an unjust war,” he told his council, “but also never to end a just war without overcoming an enemy.”

Charles proved to be a lion, not a cub, and a lion with very sharp teeth and claws. In spite of his youth, the Swedish king was one of history’s great battlefield commanders, a general of real genius who could inspire as well as lead. Over the course of the next seven years Charles XII defeated his enemies in a series of masterstrokes that amazed Europe and created a legend. He first defeated Denmark, a junior partner in the anti-Swedish coalition, then turned his attention to Russia.

Routing the Russians at Narva

In the fall of 1700, Peter was besieging Swedish-held Narva with a large army, and Charles moved east to confront the Czar. The Swedish army was a well-trained and professional force, led by talented commanders and a king of real genius. It was these factors that offset Swedish weakness in numbers. Estimates vary, but Charles was outnumbered 4 to 1, and some say 5 to 1. Some 8 to 10,000 Swedes were marching against 40,000 Russians. The Swedes marched through the howling fury of a snowstorm because, as Charles explained, “with the storm at our back, they will never see how few we are.”

The Battle of Narva was a great Swedish victory; the Russians were not merely defeated, they were utterly routed. In fairness to the Russians, most of Peter’s troops were raw recruits, in some respects an armed mob. Still, Charles’ victory was a triumph over the odds, and Narva was a battle that confirmed him as one of the era’s great soldiers.

The Height of the Swedish Empire

Poland and Augustus were Charles’ next target. By 1702 he had defeated the Saxons, Poles and Russians in a series of battles in which he was usually outnumbered. His legend grew, fueled by feats of incredible daring. For example, the king captured the great city of Cracow with little more than audacity and the weight of his growing reputation. The Swedish king rode up to the gates of the city with only three hundred cavalrymen, drew rein, and shouted, “Open the gates!” When the Cracow commander peered out, Charles hit him in the face with a riding crop. Swedish soldiers pushed through the gates, and Cracow fell without a blow—except for the one applied by the king’s riding crop.

More victories followed, and by 1706 Charles XII and his army found themselves in Saxony, deep in the heart of central Europe. Augustus had been dethroned as King of Poland and Stanislas, a man friendly to Sweden, put in his place. Charles was at the height of his power; Sweden’s military reputation stood at an all-time high, and European dignitaries came to the king’s lodgings at Altranstadt to pay court.

The Swedish Invasion of Russia

While Charles was preoccupied in Poland and Saxony, Peter had at least partly regained the initiative lost on the snowy fields of Narva. With the Swedish king far away—at least for the moment—Peter took a slice of Ingria that fronted the Gulf of Finland, an arm of the Baltic. When Peter came down to look at his newly acquired territory, his attention focused on the mouth of the Neva River, a sinuous stream that snakes its way past a series of marshes and forests and waterlogged islands before emptying into the Gulf of Finland.

The site was desolate, windswept and uninviting—and the last place to build a major city. Officially founded in 1703, St. Petersburg rose from these marshy bogs, Peter’s cherished “window on the west” that would be a conduit for western trade, ideas and technology. But Peter knew he still had Charles to contend with. The Czar sent out peace feelers to the victorious Swedish king, but they were rejected out of hand. For one thing, Peter refused to give up St. Petersburg, still technically Swedish territory, and for another Charles probably felt the Swedes would have no real peace until the Czar was not just defeated, but toppled from his throne.

And so it was that Charles XII decided to invade Russia. With the advantage of hindsight, Charles would have been well advised to treat with Peter. While Charles was busy elsewhere the Russians had occupied Livonia, Estonia and Ingria. The Czar offered to return these lands as part of an overall peace package but St. Petersburg, his toehold on the sea, refused to relinquish.

Charles XII: An Uncompromising King

In 1707 King Charles XII was a far different man from the callow youth who had gone to war in 1700. His face was pocked with smallpox scars—common enough in that era—and bronzed by the sun. Campaigning in all weathers had aged his skin, and crows’-feet gathered at the corners of his blue eyes. Charles did not wear the curled periwig that was the fashion of those days, so viewers could see that he was rapidly balding at the temples, an island of curls staying in the center of his forehead. Charles was tall, about 5’9″, and his height was accentuated by his black, hip-length cavalry boots. The king usually wore a blue Swedish uniform, and on campaign he would often not change his clothes for days at a time.

Charles was a soldier whose ascetic habits are reminiscent of the Knights Templars and other military orders that flourished in the Middle Ages. He led a spartan life, and avoided strong drink. It was as if he preferred the intoxication of battle to the intoxication of liquor. He also had no mistresses, unusual for the time, and was celibate his entire life. If he had a mistress, it was war; real women seemed to be an unnecessary distraction.

As a commander, Charles excelled in the offensive. He had an excellent eye for terrain, and had the ability to size up an enemy’s strength or weakness at a single glance. He was an excellent tactician, not afraid to break the rules if required. In the 18th century armies went into winter quarters, “hibernating” until spring brought better weather. The King of Sweden spurned such conventional wisdom, and actually conducted operations through snow and storm.

Charles wanted to punish his enemies for their aggression, and as the years passed this righteous anger hardened into near obsession. The king refused to compromise even when his victories might have given him a negotiated peace favorable to Sweden. The very qualities that made Charles an outstanding battlefield general did not transfer well on the political and diplomatic fronts. Audacity became rashness, confidence in himself a crippling inability to accept reality. These unfortunate tendencies were to bear bitter fruit at Poltava.

Charles might have marched to the Baltic, recapturing the provinces Peter had so lately seized. Once on the Baltic shores, the Swedes could be supplied and reinforced by sea. St. Petersburg might well be captured, and the Russian presence on the Baltic erased forever. But to the Swedish king these were half-measures. Narva had not destroyed Peter, so why should a Baltic campaign? No, Charles was going to invade Russia, topple Peter, and dictate a Swedish peace within the walls of the Kremlin.

Charge Across the Nieman River Line

On August 27, 1707 Charles set out from Altranstadt to embark on the invasion of Russia. The Swedish army consisted of more than 32,000 men; other units would bolster the force to over 40,000. The Swedes wore new uniforms and were well equipped; one awed spectator said, “I cannot express how fine a show the Swedes make: broad, plump, sturdy fellows in blue-and-yellow uniforms.” Flags flying, drums beating, the cheers of German peasants ringing in their ears, the Swedes embarked on their great adventure. Long blue snakes of men trudged ever eastward over the dusty roads, their ultimate goal Moscow.

Russia’s first line of defense was a series of rivers that ran north–south, including the Vistula, the Nieman and the Dnieper. The first river to be crossed was the Vistula, which the Swedes passed between December 28 and 31, 1707. Conditions were cold, the Vistula icy, but the Swedes were northerners and inured to such winter conditions.

Charles now marched toward Lithuania and Grodno, key to the Nieman River line. Up to this point the Russians had retreated before Charles—would they fight now? Charles, impetuous as ever, took an advanced party of some 650 cavalry-elite Guards troopers, and pushed on to the river. Upon arrival, he saw to his relief that the bridge across the Nieman was intact. The span was guarded by two thousand Russian horsemen; the city of Grodno was nearby.

The Swedish king led a charge across the bridge, Charles personally dispatching two Russians in the melee. Such boldness reaped rich rewards; Charles captured the bridge and camped near Grodno while waiting for the rest of his army to come up. Little did he know that Peter himself was in the city with considerable forces. The Russians evacuated Grodno under the mistaken impression they were dealing with the entire Swedish army. Discovering his error, Peter dispatched three thousand cavalry to try and capture Charles, but the attempt failed.

The Burden of Resupplying the Swedish Army

The Swedish army went into winter quarters in Lithuania till June. Then, with summer’s approach, Charles crossed the Berezina at Borisov, completely outflanking the Russians. One by one Russia’s protective “moats” had been crossed, so natural defense would have to give way to battlefield decisions.

The Russians made a stand at the Battle of Golovchin, where Swedish brilliance finally triumphed over Russian courage. But the Russians were no longer an armed rabble; they were now fighting soldiers. Before long Charles and his weary but victorious troops found themselves at Mogilev on the Dnieper River. Moscow was still some three hundred miles away, but it was only July and much good campaigning weather remained. At the time the Dnieper marked the boundary between Lithuania and Russia proper. In a sense, then, only now would the invasion of Russia begin.

The Swedish army stayed at Mogilev for a month, 35,000 men waiting for a vital supply train coming from Riga. General Count Adam Lewenhaupt, Governor of Swedish Courland, had been ordered to gather what troops and supplies he could and join the King’s main force. It was roughly four hundred miles from Riga to Mogilev, an estimated journey of two months.

The estimates proved overly optimistic. It took time to assemble a large supply train and make ready the 7,500 infantry and five thousand cavalry escort. By the time the supply column set out, Lewenhaupt was already behind schedule. Progress was slow because the heavy-laden wagons had to painfully roll through roads that were scarcely more than muddy tracks.

Charles’ great plans were starting to unravel, but he was still confident of victory. The king was visited by Ivan Mazeppa, Hetman (leader) of the Ukrainian Cossacks, whose territories were at least nominally Russian. Mazeppa wanted to throw off the Russian yoke, and told Charles he could supply an army of 30,000 Cossacks.

The Cossacks were the legendary horsemen of the plains, a hard-riding, hard-drinking semi-military caste with a well-deserved reputation for freebooting. A potential alliance would revive Charles’ faltering campaign, but in other matters the situation was growing critical. The king felt he had to resume the offensive, yet how much longer could he wait for the laggard—yet crucial—supply train with its artillery and reinforcements?

An Act of “Strategic Insanity”

In August, 1708 Charles’ army began again to move, and the Swedes found themselves at Tatarsk, on the road to Smolensk and Moscow. Yet it was plain the country ahead was utterly devastated, the Russians resorting to a scorched-earth policy. The horizon glowed red with the light of burning villages and torched fields.

Charles decided to turn south, temporarily abandoning his drive on Moscow. At that moment, Lewenhaupt’s supply column was still 90 miles away (some sources say 60) from the main Swedish army under the king. Many military historians believe Charles should have linked up with his supply train, and that not to do so was an act of “strategical insanity.”

In any event, after three back-breaking months on the road, the supply column finally reached the Dnieper River. This it crossed successfully, but the Russians were now on its trail. Finally, Lewenhaupt was cornered and forced to battle.

After heavy fighting Lewenhaupt ordered the precious wagons and their contents be burned lest they fall into Russians hands. Crucial supplies hauled five hundred tortuous miles were put to the torch. The lapping flames that consumed the supplies were also the bonfire of Swedish hopes. Lewenhaupt and some six thousand survivors managed to reach Charles and the main army, but it was a hollow triumph. More bad news followed: Swedish General Lybecker had advanced on St. Petersburg from Finland, only to be heavily repulsed.

The loss of the supply train was a bitter blow, but Swedish morale was raised by the arrival of Mazeppa and 1,500 Cossacks. But before Mazeppa could fully raise the Cossack host, Peter moved swiftly to checkmate his designs. Peter’s subordinate Prince Alexander Menshikov captured Baturin, the Ukrainian Cossack capital. He soon had Mazeppa deposed and a new pro-Russian henchman installed in his place. The Ukrainian Cossack rebellion was neatly nipped in the bud.

In the Middle of a “Little Ice Age”

Charles went into winter quarters, not knowing the winter of 1708-1709 was going to be the worst in living memory. Modern climatologists theorize that in the late-17th and early-18th centuries the world was in the grip of a “Little Ice Age,” where temperatures grew increasingly colder. If that is so, the winter of 1708-1709 was the worst of an already-frigid period.

All Europe shivered under a cold mantle of ice and snow. It was bad enough in the cities, but in the open spaces of the Ukraine it was worse. Birds fell dead from trees, and it was said saliva would freeze solid before it hit the ground. Swedish sentries froze to death on guard duty and frostbite caused the loss of fingers, toes, noses, and even private parts. Charles himself was a frostbite victim, but saved his nose and cheeks by rubbing them with snow.

By April 1709 it was clear the Swedish army had survived its ordeal, though perhaps three thousand men had frozen to death and another two thousand had been crippled by frostbite. Charles had won a few more victories over the winter, but in a war of attrition the Russians were bound to win. The Swedes were capable of offensive action—at Kronokutsk Charles defeated seven thousand Russians with four hundred men, and at Oposzanaya routed five thousand Russians with a mere three hundred troops—but these were to be the last entries in the legend of Charles XII, the last triumphs against the odds.

Poltava Besieged

And so it was that Charles decided to take Poltava. He ordered King Stanislas of Poland to join him with reinforcements, and though the Mazeppa rebellion was dead, the Zaporozhsy Cossacks promised fresh aid. Fresh hopes of Swedish victory blossomed with the wild hyacinths that poked up along the banks of the Vorskla.

Czar Peter wanted to relieve Poltava and confront his great adversary, but to do so he had to get his 40,000-man army across the Vorskla. A likely ford was found at Petrovka, but the Swedes also knew about it. Charles intended to let Peter partly cross, then fall on him before the rest of the Russian army forded the river. These Swedish designs might have borne some fruit, but Charles was wounded in the foot during a reconnaissance. The musket ball had torn up the sole of his left foot, and though he dismissed the injury it became badly infected. The king grew feverish, and while he hovered between life and death, Peter crossed the Vorskla.

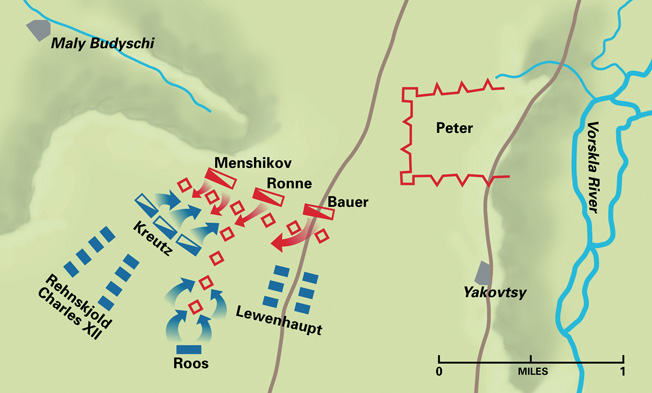

The Russian army moved to a location near the village of Yakovtsy, a scant four miles from besieged Poltava, and began to build a large entrenched camp. The camp was square, its eastern face overlooking the broad Vorskla. The river offered protection, but its banks were so steep and the river so broad that retreat would have been all but impossible. To the north, thick woods acted like a buffer, and to the south deep gullies and ravines seamed the land. The only possible place to attack the camp was from the west, which was fronted by a broad plain.

Naturally the western rampart was the most fortified side of the Russian camp. Russian soldiers had thrown up a wall there that was studded with 70 cannon and fronted by a six-foot ditch. Russian infantry in coats of blue, green and red pitched their tents within the sheltering confines of the camp. Fifty-eight battalions totaling some 32,000 men garrisoned the entrenched camp, while on a plain just beyond, Russian cavalry and dragoons milled about.

Czar Peter was still not satisfied. Any Swedish attack would have to come from the south, and the approaches to the broad plain narrowed about a mile from camp. Peter decided to “plug” this gap by building a line of six redoubts. Once again Russian soldiers laid down their muskets and took up their spades, throwing up four-sided earthworks that rose a hundred feet high and were spaced about three hundred feet apart—within the maximum range of a musket shot. The redoubts were garrisoned by green-coated troops of the Belgorodsky Regiment, and parts of the Nekludov and Nechaev regiments.

Each redoubt was a small fortress manned by several hundred men and one or two cannon. They would blunt any Swedish attack, and also form a kind of advance warning line for the main Russian camp.

Carl Gustav Rehnskjold in Charge of the Swedish Army

By Sunday, June 27 Charles was well enough to begin to discuss a plan of battle. Peter’s entrenched camp was an irresistible lure to the Swedish king, a siren’s call to possible victory. Charles was not stupid; he knew he was outnumbered, but was confident Swedish discipline, firepower and shock action would carry the day. If the Swedes attacked with energy and resolution, the road to the ford could be cut and Peter and the entire Russian army would be trapped inside their entrenched camp with the river at their backs.

Charles, however, was still incapacitated by his wounded foot and unable to ride a horse. He was forced to relinquish command to 58-year-old Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskjold, though, of course, Charles would be available for consultation. Charles planned to accompany the army on a litter, but his wound made him more good luck charm than active general.

Rehnskjold was a good independent commander, but loathed some of his subordinates, and the feeling was mutual. There seems to have been a breakdown in communication, with subordinate officers kept in the dark over the specifics of Charles’ and Rehnskjold’s plans. No doubt the Swedish generals knew what was going on in general terms, but lack of complete information was going to have fatal consequences.

The Vastly Outnumbered Swedish Army

Night fell, but as the Swedes waited for dawn and the start of battle, ominous sounds of “knocking and hewing” could be heard coming from the direction of the Russian camp. A quick reconnaissance confirmed the worst: The Russians were working on four new redoubts, the new line at right angles to the original six to form a “T” shape. These new redoubts pointed in the direction of the Swedes, and would act as a breakwater or “plow” to split their attack in two.

There was not a moment to lose. Two of the new redoubts were unfinished, and if the Swedes moved with speed and resolution the new emplacements would be passed before they became fully operational. Charles’ basic plan was to move through the redoubts as fast as possible, ignoring casualties inflicted by their muskets and cannon. While the bulk of the Swedish army squeezed through to the plain beyond, some units would be assigned to keep the redoubts preoccupied. If they could take one or more of the redoubts, so much the better, but their primary mission was screening and masking the Russian earthworks.

Once past the redoubts the Swedish army would go into battle formation on the plain, in essence daring the Russians to come out and fight. As always, estimates vary, but battle, sickness and winter-weather casualties had seriously reduced the Swedish army over the course of two years’ hard campaigning. Charles XII once had around 41,000 men; now some estimates place his fighting forces at perhaps 19,000 effectives. The Russians had about 40,000, but the balance was even worse than 2-to-1.

Rehnskjold had wanted to abandon the siege of Poltava in order to concentrate the maximum number of men for the effort, but Charles had refused. Thus, two thousand Swedes continued the siege. Another 2,400 guarded the baggage, and 1,200 kept a watchful eye along the Vorskla to prevent a flank attack The six thousand Cossacks under Mazeppa were kept in camp. All of these deductions gave Rehnskjold about 12,500 men to defeat 41,000 Russians.

Cold Steel Against the Russian Guns

The Swedish army was placed into three major divisions of five columns. The left division was under Field Marshal Rehnskjold, and consisted of two columns of eight infantry battalions. The center division was under Gen. Carl Gustav Roos, one column of four infantry battalions. It was Roos who was given the task of capturing or masking the redoubts. The right division was led by Gen. Count Adam Lewenhaupt, two columns and six infantry battalions.

The king was with Rehnskjold’s division, and was being carried in a litter in the midst of the Swedish Guards battalions. His injured left foot was freshly bandaged, but otherwise he was fully uniformed, his drawn sword laying by his side.

The Swedish army moved out just as it was growing light, and soon the first bright rays of the summer sun peeked over the treetops to flash and sparkle on their fixed bayonets. They marched as if on parade, seven thousand Swedish infantry in serried ranks dressed in blue coats and yellow turnbacks, black tricorn hats perched on their heads. Swedish cavalry trotted nearby, but only four guns. True, powder stocks were low, but Rehnskjold was a cavalryman who hated artillery, and the Swedes had faith in the shock action of cold steel.

The Swedes made a magnificent show, a blue-and-yellow wave that drew ever closer to the Russian redoubts. On closer inspection, their blue coats were faded, worn and patched from two years of campaigning, and toes peeked through worn boots. They were heavily outnumbered, and deep within enemy territory, though they were used to achieving the impossible. But could they do it again?

Fight For the Third Redoubt

Russian artillery began to fire at the advancing blue wall, muzzles spitting out a hail of iron balls in gouts of smoke and flame. Soldiers were disemboweled, lost limbs, or were decapitated in sprays of blood and flesh, but the Swedes pressed on without flinching. Swedish grenadiers from Roos’ division reached the first redoubt, spilling over the lip of the earthworks like a swarm of blue ants. Russian soldiers emptied muskets into their attackers then fought on with the bayonet, but they were no match for these Swedish veterans. The first redoubt fell, as did the second, but the third redoubt proved a much tougher proposition.

When the initial assault was repulsed, General Roos ordered a second, more determined attack on the third redoubt. This was entirely against the spirit, if not the letter, of his orders. Once repulsed, he should have moved on to the rendezvous point on the plain beyond. Instead, Roos seemed determined to take the redoubt, compounding the error by adding additional battalions from other sources to add weight to the assault. Thus, more than one-third of the Swedish infantry—about 2,600 men—were being wasted on an unimportant objective. If Roos had moved on, the redoubts would have been neutralized, players of the first act now reduced to spectators of a larger contest.

The Swedish Ga Pa

Meanwhile the rest of the Swedish infantry saw Russian cavalry pouring through the gaps that separated the six original redoubts. The infantry halted, and with the cry “Advance cavalry!” Swedish horsemen galloped forward with swords drawn. A favorite Swedish tactic was the ga pa, an aggressive offense that was unique among European cavalry. Swedish cavalrymen would move forward in chevron formations, horses so close their riders locked knee to knee.

The Swedish chevrons galloped into the Russians, a solid wall of horseflesh and steel. The battle between the rival horsemen raged for an hour, a seething, milling mass of milling, rearing horses and dueling troopers. Thousands of swords hacked and parried, and pistols were discharged at close range. Some versions say the Russian cavalry was routed; others say that Peter himself ordered a fallback. In any case, the bloodied Russian cavalry retired.

The Loss of Roos’ Force

Dirty-white skeins of smoke drifted and eddied over the battlefield, to mix with clouds of dust kicked up by the pounding hoofs of the cavalry. Disoriented by the smoke and dust, and wanting to get out of range of the Russian redoubts, Lewenhaupt led his six battalions far to the right. His path led him in the direction of Peter’s main encampment. Lewenhaupt liked independent command, and was not troubled by the fact that each step took him farther from the main Swedish force.

Lewenhaupt made preparations to assault the southern flank of the main Russian encampment, an act of suicidal bravery, even lunacy, without adequate support. He was supremely confident that his 2,400 men could break into the Russian camp and take it by storm—never mind that that camp held over 30,000 enemy troops. He was on the point of ordering an advance when a messenger a “loyal servant of the king,” brought orders to halt. Lewenhaupt was furious, but the orders probably saved him from annihilation.

Meanwhile Roos was still trying to take the third and fourth redoubts, but he succeeded in nothing but wasting precious lives. After taking 40 percent casualties, Roos finally came to his senses. He was like a man awakened from a trance—suddenly he realized he was isolated from the main body of Swedish troops. But where was the main body under Rehnskjold and Charles? Roos didn’t have a clue.

Roos retreated to the east, hoping to take shelter in the woods. Menshikov and a force of some six thousand infantry and cavalry pursued him, and soon Roos was cornered. The Swedes fought courageously, but Roos and his whole force were compelled to surrender.

Lewenhaupt managed meanwhile to rejoin Charles and Rehnskjold, though he was still angered that he had been unable to assault the main Russian camp. Rehnskjold and Charles had about four thousand to five thousand infantry, and the Swedes were outnumbered about 7-1. Now, too late, Charles realized he should have concentrated his forces.

Under Russian Artillery Fire

The main Swedish force was on its own; there was nothing left to do but order an attack as planned. About this time Peter’s army was leaving the entrenched camp, taking up the gauntlet for battle. The Czar arranged his men in two lines, the first consisting of 24 battalions of 14,000 men, and the second 18 battalions of 24,000 men. Thus, five thousand Swedes were opposing 24,000 Russians—and the latter figure did not include the nine battalions Peter had in reserve in the entrenched camp. The Russians had 70 cannon in operation, the Swedes four.

The Swedes advanced, a thin smear of blue and yellow stretched in a wide arc to make their pitifully small numbers seem larger. Drums beat a brave and steady tattoo, scissoring legs rose and fell in time with the music, and bayonets gleamed in the rays of the late morning sun. The Russian artillery began to fire as soon as the Swedes were in range, a rain of cannonballs turning straight ranks into red ruin.

Sweating Russian cannoneers, conspicuous in their gaudy red coats, worked their pieces with a will, showing they had learned much since Narva. Cannon discharged with a deafening roar, the recoil knocking them back on their trails, only to be manhandled forward, sponged, loaded and fired again. Hurtling Russian cannonballs did terrible execution, punching bloody gaps in the Swedish ranks, but the blue infantry still came on.

Swedish Lines Broken

Then it was the turn of the Russian infantry, which leveled their muskets and began to pour a steady round of volleys into the advancing enemy. Muskets pumped lead and smoke, and gun butts slammed into shoulders with each successive volley. Swedish ranks were thoroughly peppered by Russian balls, but the bluecoats did not fire a single shot in return. Cold steel, not hot lead, was at the heart of Swedish tactics.

In spite of the mounting odds against them, some of the Swedish infantry actually managed to reach the first Russian line. It was now a matter of hand-to-hand fighting, and the Swedes excelled in personal combat. The Swedes actually achieved a breakthrough on the right, led by the veteran Guards battalions. Russian units wavered, then fell back in some disorder, impaled and slashed by Swedish bayonets. They even captured a few Russian cannon, turned the pieces around, and gave the retreating Muscovites a taste of their own medicine.

For one precious, fleeting moment, it looked like Narva was about to be repeated. Lewenhaupt had achieved a breakthrough, and now looked in vain for cavalry to exploit the movement and continue the victorious momentum, but there was none to be found. The moment of possible Swedish victory, if there ever was one, passed forever. The Swedish left wing was being shredded by a heavy Russian artillery barrage, and a gap opened up between the two wings of Charles’ army. Czar Peter saw what was happening and sent in large masses of Russian infantry into the yawning gap. Now the Swedish line, already fragile, snapped in two.

Close Encounters With Death For the Two Imperial Leaders

The tables turned, and even the Swedish right wing found itself in difficulty. Its initial success doomed it, because it was now deep within the Russian lines with no support. Swedish cavalry formed too late to be effective, and had been distracted by Russian movements on other parts of the field. Only 50 Swedish troopers belatedly arrived to support their shattered infantry, and this handful were cut down with impunity. The Swedish infantry were now islands of desperately fighting men drowning in a sea of Russians. Survival, not victory, was the primary concern.

Peter the Great risked his life time and again, because the Czar’s giant size made him a conspicuous target. He was on horseback, dressed in the green and red uniform of the Preobrazhenski Guards, a large officer’s gorget and ribbon of the Order of St. Andrew on his chest. One musket ball shot his tricorn hat off, and another actually hit his chest, but was stopped by a religious icon he wore. It was also a miracle that Charles XII was not killed or captured; most of his bearers were slain or wounded, and his litter was smashed by a Russian cannonball.

The Swedish army dissolved into chaos, though some units like the Guards resisted until overwhelmed. A officer gave Charles a horse, but it was killed from under him. Somehow, the king got another mount and made good his escape. He reached the comparative safety of the Swedish camp with the wreck of his army, clinging to his horse. Charles was in great pain, since his wound had reopened and his foot was pouring a bloody trail behind him.

“The Last Stone Has Been Laid to the Foundation of St. Petersburg”

One estimate puts Swedish losses at 6,900 dead and 2,700 prisoners. Many high-ranking Swedish officers were caught in the Russian net, including Field Marshal Rhenskjold. Russian losses were a comparatively light at 1,345 killed and 3,290 wounded.

The broken Swedish army retreated toward the Dinner River; unlike Napoleon’s Grand Armee in December 1812, they were a disciplined fighting force capable of inflicting damage. But eventually most of the Swedes were surrounded and captured, though Charles XII managed to escape to Turkish territory with six hundred survivors. Charles’ flight cannot be mistaken for cowardice; if the King of Sweden had been captured, he would have been used by the Russians as a valuable pawn against his country.

The battle fought on June 28, 1709 changed the course of both Russian and European history. Poltava marked Russia’s entry onto the European stage and her debut as a major power. For Peter the Great, the battle was a vindication of his westernizing policies. As the Czar wrote in the heady afterglow of Poltava, “Now, with God’s help. The last stone has been laid to the foundation of St. Petersburg.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments