By Eric Niderost

The afternoon of May 30, 1942, found Clyde Sarah waiting for his girlfriend Ida on Estudillo Avenue, one of the main thoroughfares in San Leandro, a small town just across the bay from San Francisco. She knew the address, so he couldn’t help wondering what was delaying her. It was Memorial Day, a time when Americans honored those who gave their lives defending the United States, and this year the event was particularly poignant.

For a little over six months, the U.S. had been at war with the Axis powers—but here in California the focus was on the Far East and Japan more than Germany. Clyde’s focus was on his missing girlfriend, not the issues of war and peace. At 22, he still had the impatience of youth, and while he waited he went into a drugstore to buy cigarettes. After he emerged from the store, pack in hand, he took up his previous position on the street corner.

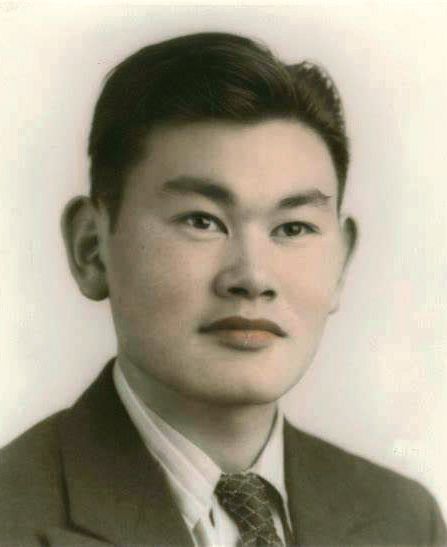

A San Leandro policeman asked Clyde if he had seen any Japanese in the area. Clyde said no, but the policeman asked to see some identification. After the officer had a look, he asked Clyde—who claimed to be “Spanish Hawaiian”—to come with him to the station. It was no use, so “Clyde” confessed that his real name was Fred Korematsu. He was a Japanese American, born in this country and so an American citizen, but the policeman was forced to arrest him for violating the government’s evacuation order. All persons of Japanese ancestry were to report to assembly centers, to be processed for “relocation” away from the west coast.

Korematsu had deliberately broken the law by refusing to be interned, saying quite simply that he was an American citizen and that he hadn’t done anything wrong. Fred acknowledged he may have technically broken a military law by not reporting, but as a civilian he was not bound to obey such directives. His courageous stand evolved into a court fight that went all the way to the Supreme Court. Korematsu’s stubborn and often lonely battle became a landmark in the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

The first laws concerning the Japanese appeared in the early 1900s, not long after the Spanish-American War. The U.S. had recently acquired Hawaii, which had a substantial Japanese immigrant population, and it wasn’t long before many of them settled on the mainland, chiefly California.

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in with the so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreement” with Japan. The pact allowed Japanese students already in the U.S. to attend “white” schools at a time when racial segregation was the norm. In return, Japan pledged to stop issuing passports to Japanese workers bound for the United States—in short, to severely limit immigration.

The initial wave of Japanese immigrants were mostly men working in agriculture. Loopholes in the pact permitted Japanese women to enter the United States, a crucial development in the formation of a viable Japanese-American community. Men could marry, start families and produce American-born children. The Japanese started to name the successive generations as the years went by. The Issei were the foreign immigrants, the Nisei the first American-born generation.

White nativist elements on the West Coast were outraged by these developments and did all in their power to restrict, and if possible expel, the Japanese and all other Asian immigrant communities. In 1905, the California state legislature passed a law that prohibited marriage between whites and “Mongolians”—a contemporary catch-all term for Asians. This law had little practical impact, because the Japanese tended to wed people of their own culture and/or ethnic identity.

Another California law, the Alien Land Act of 1913, was far more troubling. This law prohibited foreign-born people who were not eligible for citizenship from owning property. Since at the time only Caucasians could be citizens, Japanese immigrants didn’t even have to be specifically mentioned. Such “aliens” could rent or lease land, but only for a maximum term of three years. Gov. Hiram Johnson made it crystal clear that the measure was designed to “protect our agricultural lands” from Japanese acquisition.

It was against this backdrop of simmering racial and ethnic tensions that Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919. His father Kakusaburo immigrated from Japan to Hawaii in 1905 as a farm laborer, a destination many Japanese favored due to the booming sugar industry. Kakusaburo found that working conditions were far from ideal, and the workers were often exploited. Higher wages drew him to California.

Kakusaburo Korematsu’s timing was fortunate. In 1913, he managed to buy some land in east Oakland, just across the bay from San Francisco, before the Alien Land Act took effect that August. Though he had no previous experience in the trade, he opened a flower nursery on his property that soon became a growing and successful concern.

Young Korematsu was a typical teenager of the Depression era 1930s, hanging out with friends and listening to the “Big Band” sounds of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey. He felt good in high school, and fully equal, but outside the classroom Fred experienced the racial prejudice that was a sad hallmark of the time. Restaurants could, and frequently did, refuse to serve Asians, and barber shops would not cut Fred’s hair because of his “oriental” face. Usually, he had to go to Chinatown to get a haircut.

Fred’s home life was a pleasant amalgam of “old country” cultural traditions and American values. When his father hired a tutor to teach the children Japanese, Fred showed little aptitude for the language and even less interest. When engaged in a conversation with his parents, he could only manage a hodgepodge of English and Japanese phrases haphazardly mixed together.

And then, in 1938, a 19-year-old Fred fell in love with Ida Botano, the daughter of Italian immigrants. At first their respective families allowed the relationship, thinking it wouldn’t last. But when they started getting serious, things quickly turned sour. Both sets of parents objected and were even horrified at the prospect of an interracial marriage.

Fred’s older brother tried to break them up, even insisting it would “kill” their mother. But Fred and Ida continued in secret and planned to get married as soon as they could. But they would have to travel out of state because interracial marriage, sometimes called “miscegenation,” was illegal in California and 37 other states.

In the meantime, the clouds of war darkened the mood of a country painfully trying to emerge from the depths of the Depression. Japan was controlled by the military, which started an aggressive war against China. The Japanese army committed many atrocities in China, most notably the rape of Nanking (today Nanjing) in December 1937. Americans started to look on Japan with distrust and revulsion, and some of that feeling was directed at Japanese Americans.

By 1940, the U.S. and Japan were on a collision course. Diplomatic efforts to end the conflict by the Roosevelt Administration had failed. In Europe, Hitler defeated France and looked poised to invade Britain. An isolationist America still hoped the vast Atlantic and Pacific oceans would protect it.

These events prompted Congress to institute the first peacetime draft in American history. Fred, now 21, was the first to register for military service. He was classified 4-F, disabled because of a gastric ulcer, but he suspected his rejection was based at least in part because he was Japanese-American.

Disappointed but still wanting to do his “bit,” Fred asked for and received permission from his father to leave the nursery business. He took a welding course and landed a job at a shipyard, where his slim frame could fit between the double bottoms of ships to work. Korematsu found he had a special aptitude for the job, and the superintendent was so impressed he wanted to make him foreman.

Fred was happy at the news, but the euphoria was short lived. The following Monday, he was told he was expelled from the welder’s union and could no longer work at the shipyard. “That was it,” Fred later recalled. “I lost my job. I was very discouraged. I wanted to be in defense work. I’m an American and I have nothing to do with Japan. And so it’s sort of an insult to me.”

Lou Hoffman, the foreman at the Golden Gate Iron Works in San Francisco, sympathized with Fred, offering him non-union contract work until the arrangement was discovered and Korematsu fired.

The December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor produced a toxic brew of racism, fear, and hysteria throughout the nation, especially in California. Rumors of Japanese sabotage and espionage spread like wildfire.

The Sacramento Bee, long noted for its anti-Japanese stance, happily fanned the flames of prejudice. The growing public feeling was that people of Japanese descent should be removed from the west coast, lest they commit sabotage or become spies for the enemy. Groups like the American Legion, the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West, the American Growers Protective Association, and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce were happy to add their voices to the growing demand for expulsions.

Lieutenant General John DeWitt of the Western Defense Command was initially doubtful, but by 1942 he said the “Japanese race is an enemy race,” and along the “vital Pacific coast over 112,000 potential enemies of Japanese extraction are at large today.”

DeWitt became the spokesman for Japanese “relocation.” In a masterpiece of convoluted, nonsensical “logic,” the general said, “…the very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.”

Roosevelt’s liberalism bowed to intense political pressure. Since the military—people like DeWitt—were making the most noise about the issue, he said the question would be decided entirely on “military grounds.”

On February 19, 1942, the president signed Executive order 9066, authorizing Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, “…whenever he or any designated commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe the military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded.”

Stimson assigned the problem to DeWitt. A Military Area No. 1 was created, which included the western halves of California, Oregon, Washington, and the southern half of Arizona. Eventually a Military Area No 2, covering the rest of the western states and Arizona was created.

On March 2, 1942, the Western Defense Command issued a Proclamation No. 1, ordering persons of Japanese ancestry to voluntarily leave the designated Military Areas. This “voluntary phase” was an abject failure, ending on March 27. After that date Japanese Americans were ordered to stay put for the moment and wait until the authorities could organize “controlled evacuation.” Just under 5,000 persons of Japanese descent left voluntarily in this period, and when the later “relocation” prison camps were established, they remained free.

Yet even before the forced removal to internment camps, the Japanese Americans were the victims of increased white paranoia. Their homes were randomly searched, and Karematsu recalled how police entered his home and confiscated cameras, flashlights, or anything that they deemed might be used for “signaling” or espionage activities.

The so-called “evacuation” of all persons of Japanese ancestry would be administered by a new government agency, the War Relocation Authority. Milton Eisenhower, the youngest brother of general and later President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was its first director. Eisenhower was strongly opposed to the idea of forced removal and hoped that temporary camps much like the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps would be set up as kinds of “halfway house” transition zones.

The Japanese Americans would find employment and living quarters in host communities in various designated states. In time they would be integrated into the host communities, or at least that was the earnest hope of Eisenhower and many WRA officials. But it was the vehement racism displayed by the various state governments that doomed his plan and led to the 10 permanent prison camps, complete with armed guards, watch towers, and barbed wire, that are chiefly remembered today.

Eisenhower chaired a western state conference on April 7, 1942, that from his point of view was an unmitigated disaster. With one exception—Colorado’s Governor Ralph Carr—the various officials were outspoken in their opposition to having any people of Japanese extraction in their states, save as prisoners behind barbed wire. The racist rhetoric that poured forth shocked and dismayed Eisenhower.

Arizona Governor Sidney Osborne declared, “We do not propose to be made a dumping ground for enemy aliens from other states. We want to keep this a white man’s country.” Wyoming’s Governor Nels Smith went even further, saying, “We will not stand being California’s dumping ground,” and if they came, “there would be a Jap hanging from every tree.” The others—save for Carr —concurred and added their own similarly racist comments.

There was no other alternative: the “relocation” prison camps would be permanent, at least for the duration of the war. There would be an intermediate stage, where “internees” would first report to assembly centers while the permanent camps were being built. Japanese Americans would usually have about a week to settle their affairs, meaning selling or giving away virtually everything they owned—businesses, homes, furniture, automobiles, even dishes, pots, pans, and pets.

The internees’ whole world would be reduced to whatever they could wear or carry in a few suitcases. Some white neighbors were sympathetic, holding Japanese possessions with the intention of returning them after the war. Sadly, many more were opportunists, using the crisis to exploit and victimize their former neighbors.

Korematsu was the proud owner of a 1938 Pontiac—“a very nice car. A sedan. I loved that car” he sadly recalled years later. He paid $800 for the car about a year and a half earlier, but with “evacuation” imminent a dealer offered only $200 for it. “That’s war,” the dealer smugly informed Korematsu almost nonchalantly. “I felt like I was robbed,” he remembered, “but there was nothing I could do about it.”

The evacuation was soon underway, with military notices sent to different sections of California informing “persons of Japanese ancestry” when and where to report for pickup to assembly centers. These assembly centers were race tracks, fairgrounds, or livestock exhibition centers.

On Friday, May 8, 1942, the Korematsu family reported as ordered to Watkins Street in Hayward, California, to catch the bus that would take them to their assembly center. Fred was not with them. In what was the most momentous decision of his life, he decided not to obey the evacuation order. He felt forced removal was wrong, a violation of his rights as an American, and he desperately wanted to stay with Ida, his fiancée.

Fred wanted to move out of state, away from the coastal Military Area, but Ida didn’t want to leave, at least not yet. As a kind of compromise, Fred rented a room in the Fruitvale area of Oakland. Ida saw an ad in the newspaper about a doctor who performed plastic surgery. Perhaps that was the answer; by this time the couple were clutching at straws.

Hopeful but still a bit dubious, Fred visited Dr B.B. Masten and discovered the address was a regular private home, not a medical clinic or hospital. Masten was a real doctor, not a quack, and told Fred he could build up his nose and eliminate much of the epicanthic fold, the distinctive “double” eyelid of many Asian peoples. The fee was $400 for such work; Fred had only $100.

Nevertheless, the doctor agreed and the procedure on Fred’s face began. But when the operation was over Korematsu was disappointed to see there was very little change in his face—he still looked Asian, and people who knew him easily recognized him. Whether it was a question of very little work done because Fred couldn’t pay the full fee will never be known.

Once Fred was arrested, he was briefly incarcerated in a San Leandro jail, then transferred to an Oakland jail before finally ending up in a military stockade in San Francisco’s Presidio. Things looked pretty grim for the young man when he received an unexpected and very welcome visitor. His name was Ernest Bestig, and he was a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union. Bestig read newspaper accounts of Fred’s arrest and wanted to help.

Bestig was, in fact, the executive director of the San Francisco branch of the ACLU and was hoping he could persuade a Japanese American to fight the various evacuation orders in court. He knew the person he chose would have to be willing to go the distance, right to the Supreme Court if necessary. The lawyer realized he had found his man—the person he was sure would stay the course no matter what difficulties might arise.

On June 12, 1942, formal charges were filed against Korematsu for deliberately staying in the Military Area No 1. According to the charges, he was more specifically guilty of not obeying Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, the evacuation order that applied to his particular section of Alameda County, California. Number 34 was the summons that the rest of his family had obeyed over a month earlier, becoming “family 21538” according to the authorities.

Fred was sent to the “assembly center” at Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, not far from San Francisco. There were several thousand “evacuees” there, including Fred’s family, but he requested to be lodged in separate quarters because his family would disapprove of his defiance of the law.

Tanforan was dirty, cramped, crowded, and certainly not designed for human habitation. The “rooms” were mostly old horse stalls that were bitterly cold at night and were infested with mice and other vermin.

But perhaps the worst of it came when he finally visited his family in the same facility. They did not completely ostracize him but made it clear that in their minds he had brought trouble, dishonor, and shame to the Korematsu name. Most members of the Japanese American community felt the same way about Fred.

According to Japanese cultural norms, one should passively, even stoically, accept adversity. The phrase used was “shikata ga nai,” or “it can’t be helped.” The family, and indeed the whole community, was trying to show their loyalty to the United States by obeying the laws that deprived them of home, livelihood, and even basic human rights. Fred, by his defiance, was rocking the boat.

Fred’s arrest and subsequent legal battles made Ida have second thoughts. Not wanting to get into trouble herself, Ida told an FBI interviewer she realized that the idea of marriage was a “mistake.” She also regretted not alerting authorities when Fred decided to stay and not be “evacuated.” To her credit, Ida did insist Fred was a loyal citizen.

On September 8, 1942, Korematsu was found guilty in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. The only witness was the FBI agent who interviewed Korematsu. As evidence the government used his altered draft card, his birth certificate, and various statements he made over time.

Korematsu could appeal, and did, but in the meantime he was sent to Topaz Relocation Camp in Utah, one of the 10 permanent camps spread throughout the United States. These relocation camps were really prison/concentration camps complete with barbed wire, watch towers, and armed guard.

Some 4,000 young adults were released from the camps to complete their college educations. In 1943, Korematsu himself was allowed to work at a pipe construction company in Toole, Utah, though he still had to report back to Topaz.

After a two-year wait, Korematsu’s hopes of justification were dashed when the Supreme Court ruled against him, 6-3. On December 18, 1944, the court majority upheld the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 and the Army’s excuse of “military necessity.” The majority opinion had a narrow focus on the issue of disobeying the Army’s evacuation order—ignoring the constitutional issue of the mass imprisonment of American citizens without due process.

By focusing on the issue narrowly, they ruled on the Japanese evacuation, not detention. And that is why another case, Ex Parte Endo, had a dramatically different outcome. Mitsuye Endo was a young Nisei woman who had obeyed the evacuation order and allowed herself to be imprisoned at the relocation camp. Only then did she allow herself to be used as a test case.

The Supreme Court unanimously ordered her immediate release, ruling that the government had no right to imprison a citizen who was law-abiding and loyal. Its rulings on the two cases were contradictory, so the Court tried to reconcile the glaring differences by implying Endo had behaved correctly, but Korematsu did not—by willfully disobeying, getting plastic surgery, trying to assume a new identity, and going “underground.”

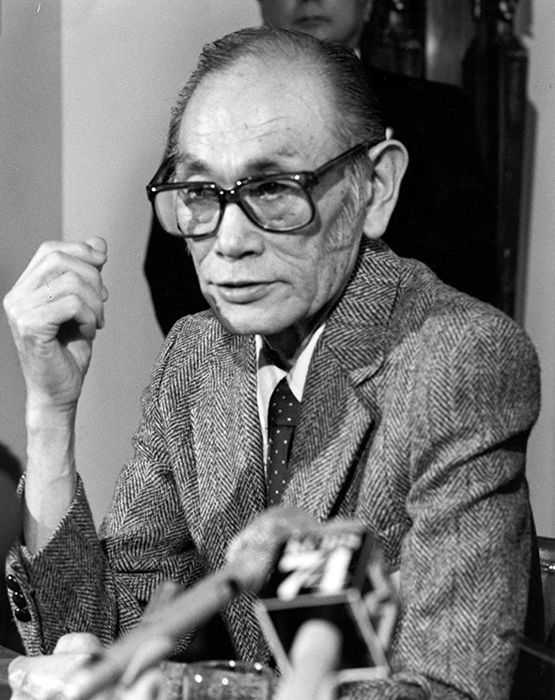

Korematsu’s case was reopened in 1983, after researchers found documents that showed the authorities deliberately withheld and/or covered up evidence that the Japanese American community was no threat to national security. Even J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI—and no friend of racial minorities—concluded that there was no evidence of Japanese American wrongdoing.

Because of the evidence hidden from the Supreme Court, Korematsu’s conviction was formally overturned on November 10, 1983. He was also honored when in 1998 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, from President Bill Clinton.

Fred Korematsu died in 2004 at the age of 86. He remained active to the end, making appearances all over the country and speaking about his experiences.

Eric Niderost is a long-time contributor to WWII History and teaches at a community college in the Bay Area of California.

The entire program of relocating Japanese-Americans was a tragedy and a disgrace. That having been said, there was no comparison to the Japanese camps that held American and British citizens like Santo Tomas in Manila. Death rate was high from mistreatment and neglect and many of those who survived ended up with permanent disabilities. My late wife and her family were internal refugees on the island of Mindanao, spending three years in the jungle. This because her father was minor official in the commonwealth government who would probably have been sent to prison or executed. In the US, the surviving detainees were given a token compensation four decades after the war. In Asia, a few Japanese who committed atrocities against detainees were hanged but most simply returned home and resumed their lives. No war is “fair” but some get a much better experience than others.