By Michael D. Hull

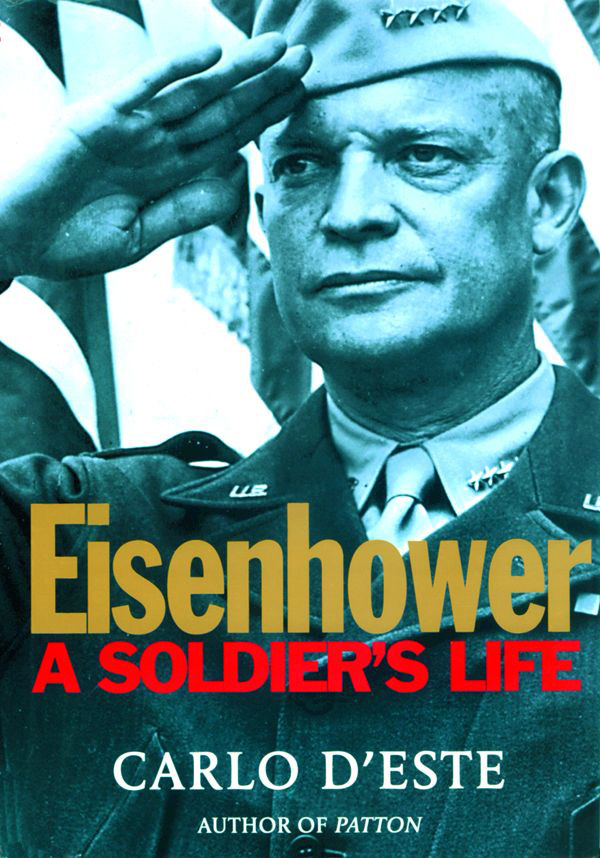

An obscure U.S. Army staff officer who had never been in action, Dwight David Eisenhower was a lieutenant colonel at the age of 50 with no visible prospects for advancement in the stagnant between-the-wars promotion system.

Yet, in just over three years and three months, he was wearing five stars and holding the highest command accorded any soldier in the Western Alliance of World War II. The fate of the war against Nazi Germany lay on his broad football shoulders early in June 1944, a responsibility of awesome potential for failure that had been faced by few military leaders in history.

“I hope to God I know what I’m doing,” he muttered on June 5, after taking a gamble on a break in the fickle English Channel weather and giving the “go” order for the 150,000-man Allied invasion of Normandy. Beneath his infectious grin and easygoing manner that exuded confidence, General Eisenhower was the world’s loneliest man in the tense hours before D-day. He was beset with concern for his men, and told his Irish-born WAC driver and private secretary, Kay Summersby, “It’s hard to look a soldier in the eye when you fear you are sending him to his death.”

Eisenhower drank one pot of coffee after another, and his smoking had increased to four packs a day. But D-day would prove to be Ike’s finest hour. The British, American, and Canadian armies scrambled ashore on that damp, dreadful morning and gained a solid foothold on the European continent. Eventual victory, coming a year later, was assured.

Eisenhower drank one pot of coffee after another, and his smoking had increased to four packs a day. But D-day would prove to be Ike’s finest hour. The British, American, and Canadian armies scrambled ashore on that damp, dreadful morning and gained a solid foothold on the European continent. Eventual victory, coming a year later, was assured.

Much has been written about this remarkable man, yet Carlo D’Este, one of the world’s premier military historians, captures Ike’s complex and contradictory character with originality and professional understanding in Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life (Henry Holt & Co., New York, 2002, 849 pp., 16 pages of photographs, 12 maps, notes, index, $35 hardcover). It is a subtly nuanced, expansive, and rewarding biography against which most previous studies pale, a masterpiece of research, insight, and narrative grace. Making full use of his papers and letters, this book focuses on Eisenhower the soldier, rather than Eisenhower the 34th U.S. President.

D’Este, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and author of landmark works on General George S. Patton, Jr., and the Sicily, Anzio-Rome, and Normandy campaigns, shows how the genial son of stern, humble pacifists in hardscrabble Kansas went to West Point to get a free education and play football, repeatedly flouted academy rules, helped to pioneer armored tactics, and endured dreary postings in steamy Panama and the Philippines. Eisenhower exhibited a flair for planning and caught the attention of John J. Pershing, Fox Conner, Douglas A. MacArthur, and George C. Marshall. He underwent a painful learning experience in North Africa in 1942-1943, in which he had to play politician as well as general, and eventually became the indispensable glue that held the Anglo-American military union together in 1944-1945.

Ike’s inspired, tactful coordinating of prima-donna subordinates, particularly Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery and Patton, is analyzed convincingly, as are his flaws: a tendency to play favorites, and some much-debated strategic moves. His controversial, slow-moving “broad-front” advance into Germany prolonged the war and was politically motivated, many historians believe.

would have quite possibly ended the campaign by Christmas and avoided much subsequent suffering and death. And it would have been far more likely if Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., recently released from the doghouse after tantrums at two field hospitals and an ill-advised public statement, had been in command of the U.S. 12th Army Group instead of General Omar N. Bradley.

The latter’s prime assets of caution and reliability were not what was needed in the final, critical phase of the campaign, says Brooks. Popular and occasionally petulant, Bradley was neither brilliant nor imaginative. In mid-August 1944, the author writes, Patton was the American general with the clearest vision of the main military objective: the destruction of the Wehrmacht. He envisioned a broad sweep by three corps down both banks of the Seine to encircle and ensure the elimination of the best German units in northwest Europe. These forces were the main impediment to an Allied thrust into Germany.

A spectacular conclusion to Operation Overlord could have been achieved, says Brooks, with Patton leading the U.S. forces while subordinate to British General Bernard L. Montgomery, the Allied ground commander. Despite their well-publicized rivalry, they respected each other and exhibited complementary strengths of risk and balance. Monty would have given him the autonomy he accorded to Bradley and, in turn, Patton could have probably implemented the same daring maneuvers to trap Germans that Bradley refused to authorize. Brooks blames Bradley (sticking inflexibly to Monty’s edict on suggested interarmy boundaries) for allowing 30,000 to 40,000 Germans to escape from the Falaise Pocket.

In his masterfully concise and well-paced distillation of the campaign from the D-day beaches to the joyful liberation of Paris, the author outlines crisply the significant battles (Caen, Villers-Bocage, Cherbourg, St. Lô, Mortain); provides useful detail on organizations, armor, infantry weapons, equipment, chivalry, and occasional atrocities; and soundly analyzes the leaders on both sides.

Recent and Recommened

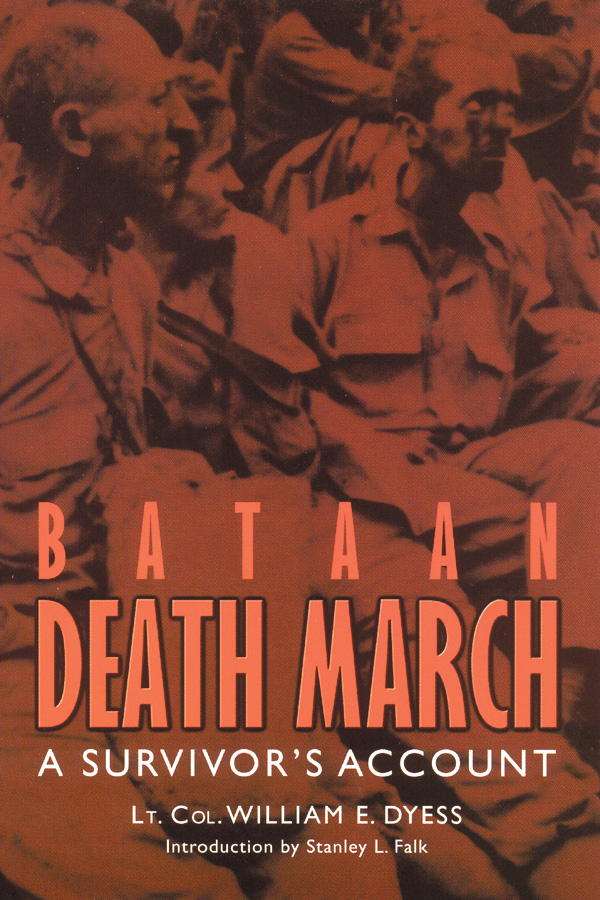

Bataan Death March by Lt. Col. William E. Dyess, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2002, 184 pp., 20 photographs, maps, appendix, $14, softcover.

Bataan Death March by Lt. Col. William E. Dyess, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2002, 184 pp., 20 photographs, maps, appendix, $14, softcover.

One of America’s earliest World War II heroes was a 6-foot-tall, slow-spoken, former Boy Scout and judge’s son from the West Texas cattle town of Albany.

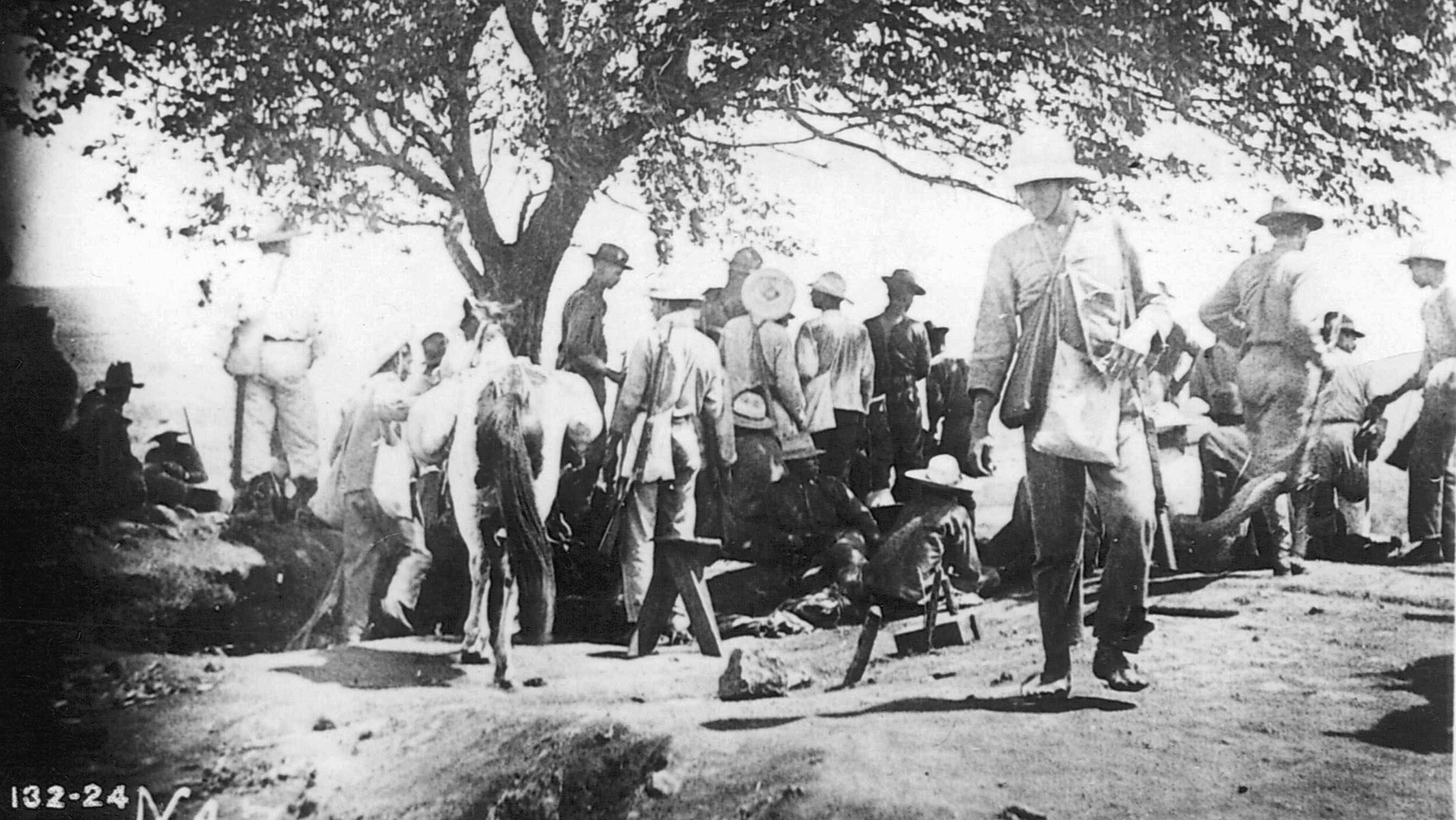

When Japanese bombers struck Clark Field in the Philippines on December 8, 1941, William Edwin Dyess, a 25-year-old Army Air Corps captain, led his Curtiss P-40 fighter group aloft to defend Manila. Later, he single-handedly attacked a Japanese task force at Subic Bay on Luzon, missed with his 500-pound bomb, but blew up supplies stored on a small island. By strafing, he exploded a 12,000-ton ship, beached another, sank two hundred-ton launches, and gunned troops and docks. The next day, Japanese radio reported that Subic Bay had been raided by a force of four-engine bombers.

When enemy troops overwhelmed the gallant but doomed American and Filipino defenders of the Bataan Peninsula, Dyess refused to leave unless his 25 officers and 175 enlisted men could also get away. The Americans surrendered on April 9, 1942, and Dyess found himself a prisoner of war along with thousands of others. He took part in the infamous 85-mile Bataan Death March to Camp O’Donnell, during which an estimated 600 Americans and 5,000 to 10,000 Filipinos perished. Dyess kept a diary that eventually became the basis for a series of LIFE magazine articles and a book, published by his wife, Marajen, after his death in 1944 while testing a P-38 Lightning fighter.

Dyess’s plain-spoken, graphic record of one of the worst atrocities of the war is a harrowing testament to both Japanese barbarism and the indomitability of the human spirit. It is a classic of its type that should not be overlooked by World War II scholars.

Dyess describes how the Japanese, unready to handle so many captives and unfettered by the codes of the Geneva Convention, subjected the prisoners to a nightmare of assault, humiliation, denial of sustenance and medical aid, and cold-blooded murder. During his six-day march under a searing tropical sun, Dyess received only a single ladle of rice and a minimum of water.

He tells how a further 1,565 Americans and 26,000 Filipinos died at Camp O’Donnell, where the prisoners were denied adequate food and medicine and were subjected to continued brutality at the hands of indifferent guards.

Eventually, after being transferred to the Cabanatuan POW camp near Manila and then the Davao penal colony on Mindanao, Dyess, having survived 361 days of captivity, was able to escape into the jungle and reach Australia aboard a U.S. submarine.

After receiving the Distinguished Service Cross with cluster, the Legion of Merit, and the Silver Star, Dyess was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

His legacy is this powerful, tragic, and absorbing narrative of courage and perseverance during America’s darkest hours. The foreword is by Stanley L. Falk, a former Air Force historian and the author of Bataan: The March of Death.

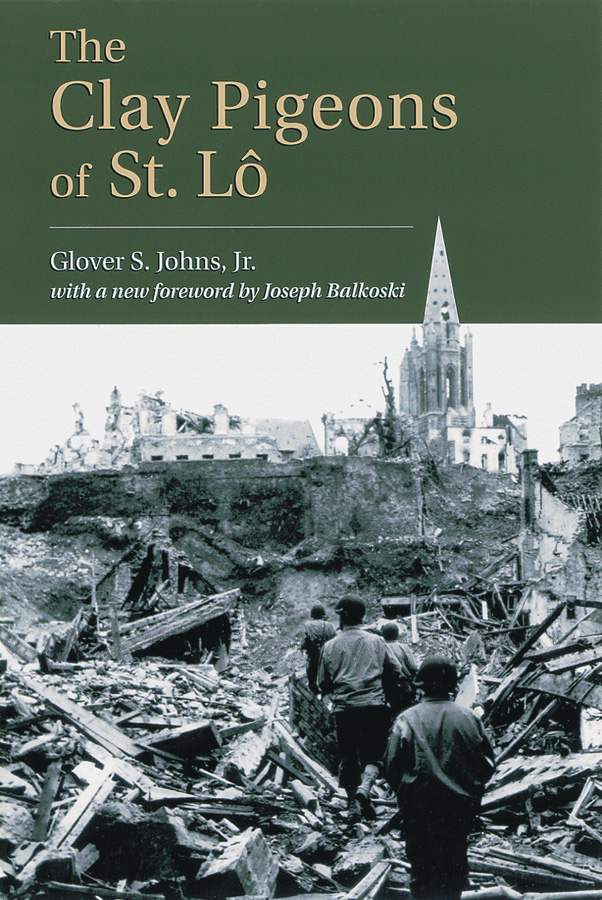

The Clay Pigeons of St.-Lô by Glover S. Johns, Jr., Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002, 257 pp., appendix, glossary, $16.95, softcover.

The Clay Pigeons of St.-Lô by Glover S. Johns, Jr., Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002, 257 pp., appendix, glossary, $16.95, softcover.

A few weeks before the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt, commander of the 29th Infantry (Blue and Gray) Division, called his senior officers together in Tavistock, Devonshire, in England.

The tough, demanding general known as “Uncle Charlie” growled prophetically, “This war is won at battalion level.… A year from today, one out of every three of you will be dead, and the toll will be higher if senior commanders don’t know their stuff.”

One of his battalion commanders was Colonel Glover S. Johns, Jr., a Virginia Military Institute graduate and leader of the 1st Battalion of the 115th Infantry Regiment. He would serve under Gerhardt for the duration of the war in Northwest Europe.

After enduring the bloody debacle at Omaha Beach, Johns’ 800 men fought their way inland toward St.-Lô, the American invaders’ first major objective. Although the historic city was intended to be taken within days of the landings, stubborn German defenders held on to it until July 18. The struggle for St.-Lô mirrored the British and Canadian armies’ bitter month-long fight around Caen to the east. And, like Caen, St.-Lô was just a pile of rubble by the time it was captured.

Colonel Johns’ unit was one of nine infantry battalions of the 29th Division, which landed at Omaha Beach. It fought through the hedge-rows, pastures, woods, and ancient villages of the Normandy bocage country, and a large number of its young men lie there still. With his plain-spoken, graphic account of those 30 days of combat, Johns saw to it that his gallant young citizen soldiers, dubbed “The Indestructible Clay Pigeons” by a war correspondent, would never be forgotten.

First published in 1958 and now available in softcover, this is an authentic World War II classic and a unique perspective of war, a saga of suspense, elation, fear, sorrow, and chagrin that is told at the foxhole level with quiet respect, a lack of heroics, and powerful simplicity. It is a page-turner that distills unforgettably the U.S. Army experience in Normandy in the summer of 1944.

From Omaha Beach to the River Elbe, Colonel Johns’ 1st Battalion lost 2,384 officers and men killed or wounded, almost three times its strength. Of these, 454 were killed in action. Its commander, who was commended for taking objectives with minimal losses, was awarded the Silver Star and Bronze Star with clusters, and a Purple Heart.

The foreword is by Joseph Balkoski, author of the acclaimed Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy.

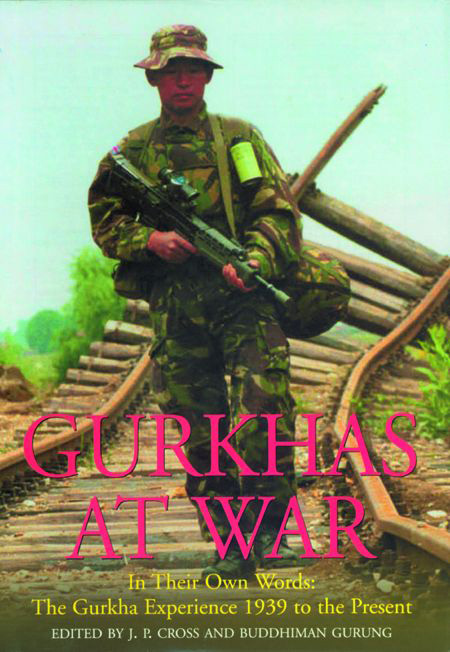

Gurkhas at War J.P. Cross and Buddhiman Gurung, eds., Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002; 320 pp., 28 photographs, 11 maps, glossary, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Gurkhas at War J.P. Cross and Buddhiman Gurung, eds., Stackpole Books (Greenhill Books), Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002; 320 pp., 28 photographs, 11 maps, glossary, index, $39.95, hardcover.

No soldiers in World War II were more brave and resilient in the face of fearsome odds and extremes of hardship than the British Army’s legendary Gurkhas.

Short, wiry, and cheerful warriors from the hills of Nepal, they fought under British officers all over the world, starting in 1817. Fiercely loyal to the Crown, they earned a reputation unrivaled in military history.

Wielding their sharp kukris (knives), they excelled in close combat and were much feared by their enemies. On one occasion during the Italian campaign of 1944-1945, several Gurkhas came across four German soldiers asleep in a trench. The Gurkhas silently decapitated two of them, but left the others unharmed so that they could wake up and appreciate their enemies’ technique.

A total of 250,280 Gurkhas joined up, and 2,734 decorations for gallantry were awarded to them, including 13 Victoria Crosses. They suffered 23,655 casualties from 1941 to 1945, slightly more than they had in World War I.

Their long and colorful story has been told before by outsiders, allies, and foes, but in this oral history the Gurkha voice is heard for the first time. Graphic first-person accounts bring to life their regiments’ sterling service with the British Army in Malaya, North Africa, Burma, India, Thailand, Syria, and Italy, with emphasis on their gallantry during the fall of Singapore and Burma and on the bloody battles at the Arakan, Monte Cassino, Kohima, and Imphal.

Being an oral history, this book is no inspired literary tour de force. But it contains much revealing detail, plain-spoken and unvarnished, on the Gurkha units, their campaigns, and the incredible feats of individual soldiers. It is long overdue. It also covers their later service in Greece, Palestine, Java, the Dwight Eisenhower did not fit the mold of the warrior hero in the tradition of Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, or Stonewall Jackson, says D’Este, yet he was every inch a soldier. His legacy is based on his unique ability to mold disparate allies, molding often-conflicting philosophies into a formidable force capable of crushing Naziism. Few other men could have pulled it off, as his contemporaries readily admitted. The grin and disarming manner of a born optimist charmed all ranks and all nationalities, the author points out, yet it concealed a towering ambition, a lifetime of study and preparation, and a determination, like Patton’s, that was one of the best-kept secrets of Ike’s success.

He may not have regarded himself as indispensable, but this portrait makes it clear that history has recorded its own verdict. Despite one or two factual slips and misspellings due to proofreading lapses, this is a riveting and provocative study, as one would expect from Colonel D’Este.

The Normandy Campaign by Victor Brooks, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 264 pp., 8 maps, photographs, index, $26, hardcover.

The Normandy Campaign by Victor Brooks, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 264 pp., 8 maps, photographs, index, $26, hardcover.

Combined with a massive Soviet offensive to the east, Operation Overlord pushed the Third Reich to the brink of defeat and resulted in its unconditional surrender almost 11 months after Allied troops stumbled out of their landing craft on the gray morning of Tuesday, June 6, 1944.

The Normandy campaign, fought by two million British, American, and Canadian soldiers in the spring and summer of 1944, was a defining moment of World War II, and one of the most decisive events of the 20th century. Allied losses were heavy. Of the 36,976 men killed in action, 14,500 were British and Canadian, 21,500 American, and the rest Poles, Frenchmen, and others. Yet these casualties paled beside those of the million German troops engaged in Normandy. By the time that the U.S. 28th (Bloody Bucket) Infantry Division marched triumphantly through Paris on August 28, the enemy had lost 240,000 killed or wounded, 210,000 missing or captured, and an additional 100,000 men besieged in French ports.

But were other outcomes reasonably possible for the Allies during this great campaign, and could the war in Northwest Europe have been ended by Christmas 1944? Yes, says Victor Brooks in his intriguing study that is distinguished by well-informed analyses and superb narrative clarity.

The most beneficial outcome of the campaign for the Allies would have been the forced capitulation or annihilation of the German Army west of the River Seine, he believes. This Indian partition, Malaysia, Brunei, Borneo, Hong Kong, Cyprus, the Falklands, the Persian Gulf, Bosnia, and East Timor.

Cross served in Asia for 39 years, chiefly with the Gurkhas, and co-editor Buddhiman is an interpreter for Habitat for Humanity volunteers.

Love Company by Donald O. Dencker, Sunflower University Press, Manhattan, Kan., 2002, 355 pp., photographs, maps, notes, appendices, glossary, index, $19.95, softcover.

A mortarman in Love Company of the 382nd Infantry Regiment, U.S. 96th Infantry (Deadeye) Division, in 1944-1945, Pfc. Donald O. Dencker spent 533 days overseas, most of them in the heat of Pacific battles.

“I was certainly not a hero,” he reported. “Most of the real heroes were killed or wounded during courageous endeavors. I just tried my best to do my duty and stay alive.” Yet he was awarded the Bronze Star for “meritorious achievement” during the bloody Okinawa campaign of April-June 1945. The citation recorded that Dencker “performed his duty with far greater courage and zeal than is ordinarily required.…”

In his memoir of infantry combat against the Japanese, Dencker, who was a 17-year-old senior at Roosevelt High School in Minneapolis at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, pays moving tribute to the Army and Marine Corps riflemen of World War II, particularly his draftee comrades of Love Company. They were “unrecognized heroes” who did “their dirty job day after day, for all knew that ultimately their luck would run out.”

In a graphic narrative that is lively, human, and better written than most of its type, Dencker describes how he and Love Company landed under fire at Leyte in the Philippines on October 20, 1944, struggled through the swamps and jungles, and fought at Dagami Heights and the Burauen airstrip. Only the author and six other men were left out of the 187 company members who had landed. Then he details the hard-fought capture of fire-swept Dick Hill, Oboe Hill, and Hen Hill on Okinawa, a nightmare of broken supply lines, heat, dust, sparse food and drinking water, torrential rains, and blood-sucking leeches.

Dencker, who served later with the 47th Infantry Division in the Korean War and is the historian of the 96th Infantry Division, has written a highly readable foxhole-level account of the Leyte and Okinawa campaigns. It is highly informative and lavishly illustrated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments