by Al Hemingway

On September 2, 1945, representatives from the Allied and Japanese governments signed the peace treaty that ended World War II.

Or did it?

In June 1944 American warships sank several Japanese troop transports. Survivors from the vessels swam to safety and reached the island of Anatahan, located approximately 75 miles north of Saipan. The island was uninhabited, and possessed steep slopes, deep ravines, and high grass.

[text_ad]

In January 1945 a B-29 bomber from the 498th Bomber Group, returning from an air raid over Japan, developed engine trouble and slammed into a grassy field. The crash killed the entire crew.

Isolated & Forgotten

The small group of Japanese who had survived the sinkings of their transports quickly cannibalized the aircraft. They utilized metal from the wreckage to manufacture makeshift knives, pots, and roofing for their huts. The plane’s oxygen tanks held their potable water, clothing was fashioned from the silk parachutes, and cords were used to make fishing lines. The aircraft’s weapons were confiscated as well.

Later in 1945, the Japanese were discovered by Chamorros who had gone to Anatahan to recover the remains of the missing bomber crew. The natives returned and testified to authorities that they had seen the Japanese soldiers and also one Okinawan woman.

Upon hearing this news, U.S. planes dropped leaflets on the island asking the soldiers to surrender. Fearing execution, the holdouts refused the request. With the small band of Japanese virtually isolated from the outside world, they were soon forgotten.

Then, after six years of this Spartan existence, Kazuko Higa, the Okinawan woman, got the attention of an American ship as she walked on the beach. When approached by a landing party, she asked to be taken from the island.

Convincing the Last ‘Robinson Crusoes’ To Surrender

Upon her arrival on Saipan, Higa told U.S. officials that the Japanese did not trust the Americans. It was also learned that the woman had a busy love life while imprisoned there and her flirtations had caused some jealousy. It seems she would “transfer her affections between at least four of the men after each mysteriously disappeared as a result of being swallowed by the waves while fishing.”

Finally, the Japanese government intervened and contacted the families of the survivors, asking them to write letters telling their loved ones that Japan had surrendered.

In addition, a letter from the governor of Kanagawa Prefecture was sent to convince the “Robinson Crusoes” to give themselves up. It read in part: “Previously, in our country, a prisoner of war lost face. That is not so now. The Emperor ordered all our people, wherever they were, to surrender peacefully. I believe you have read letters from your family which said not to worry which will give you confidence to give yourself up to the Americans. In the box of new letters sent to you we are enclosing a piece of white cloth with which you can signal the Navy boat. You do not have to worry. The Americans will give you their best attention and kindness until you are returned to our country.”

This message was dropped on June 26, 1951. Several days later, the Japanese waved the white flag of surrender.

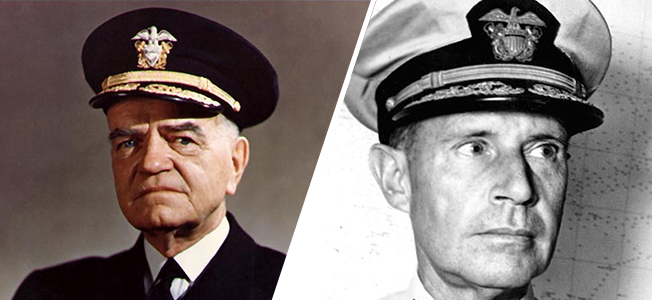

On June 30, 1951, the USS Cocopa, a U.S. Navy tug, appeared offshore. Lieutenant Commander James B. Johnson, the ship’s commanding officer, and Mr. Ken Akatani, an interpreter, made their way to the beach in a rubber boat.

Once ashore, Johnson and Akatani met with the Japanese to accept their formal surrender, now dubbed Operation Removal by the U.S. Navy. With their meager belongings wrapped in cloth, the survivors were brought aboard the tug and sent to Guam. Once there, they boarded a Navy plane and were flown to Japan to be reunited with their families.

Other stories of Japanese military personnel holding out in remote South Pacific locales continued for years.

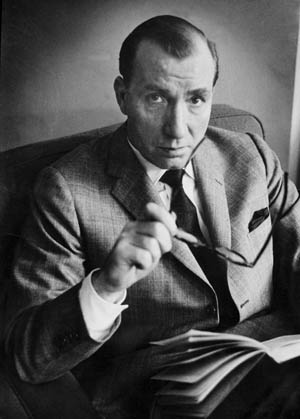

My father often told us about Anatahan but said the true story could never be told until everyone involved had passed away. Kan (Ken) AKATANI passed away in 2000 in White Plains, New York.