By Al Hemingway

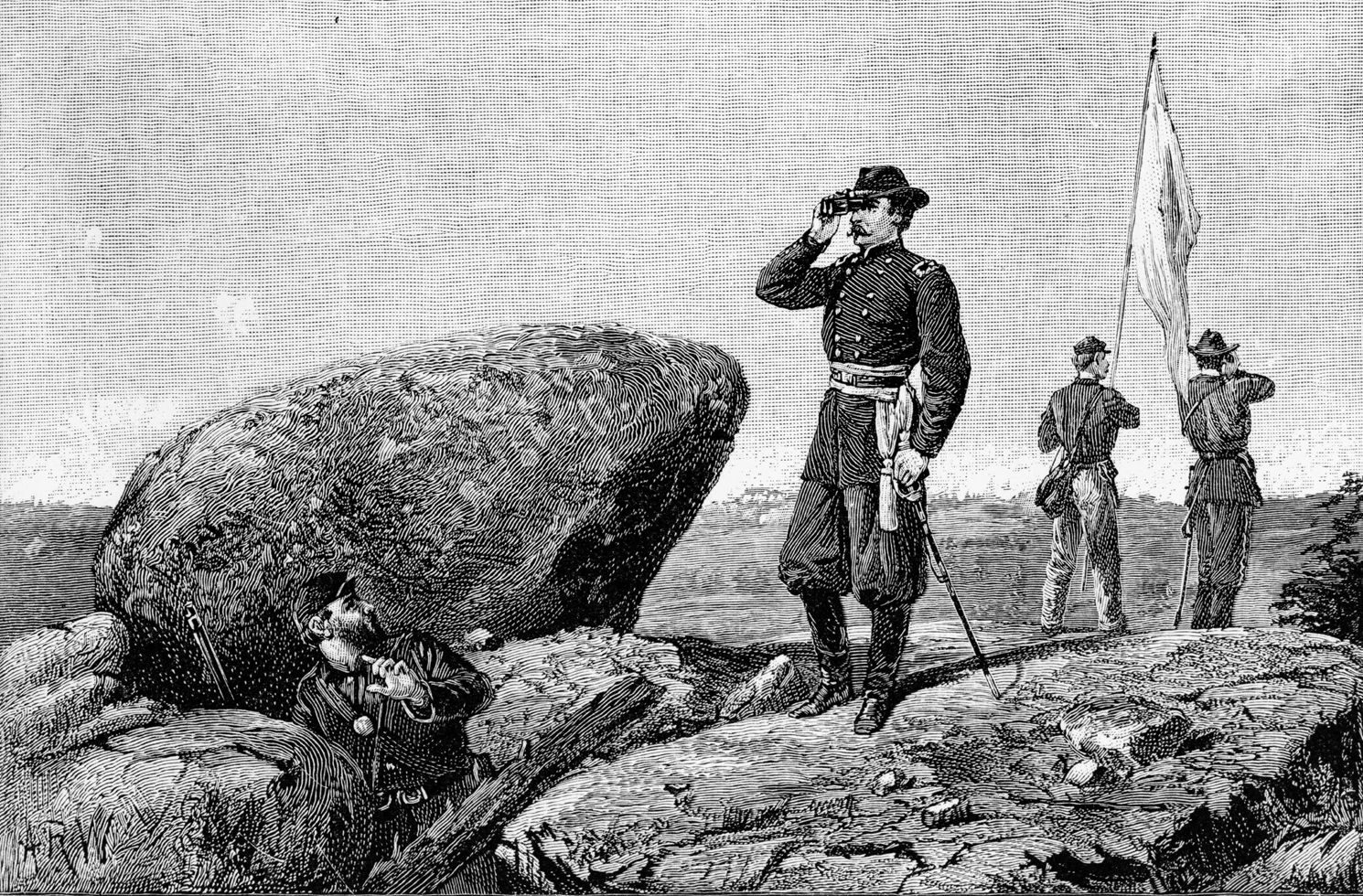

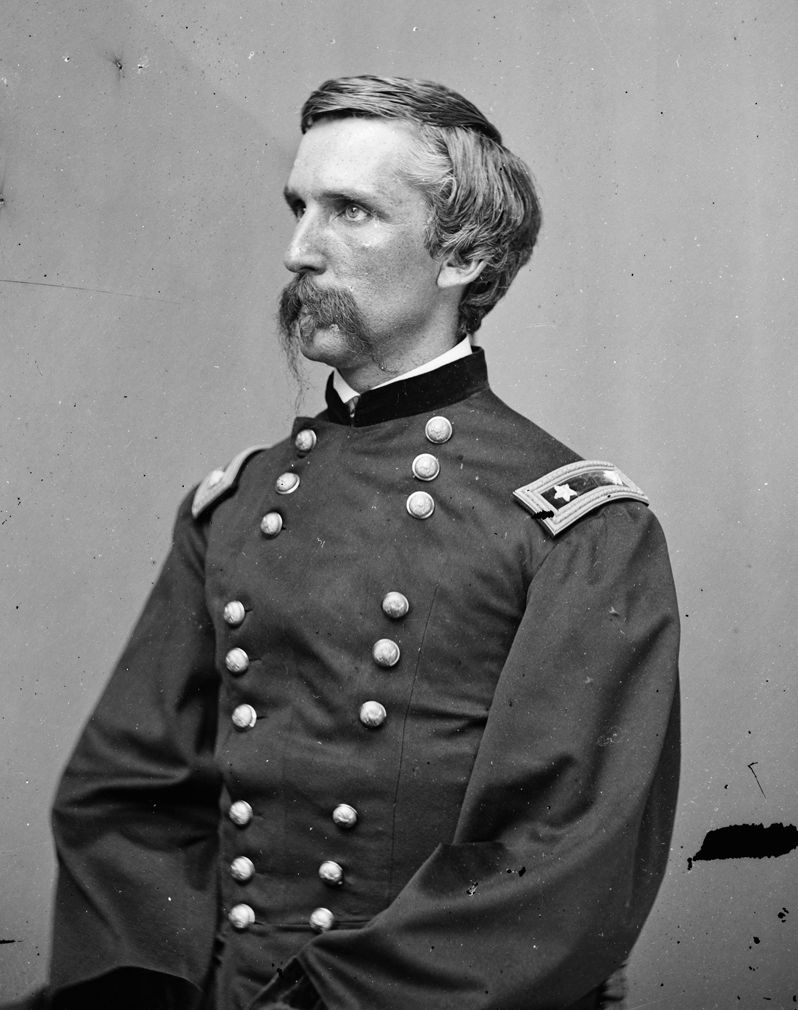

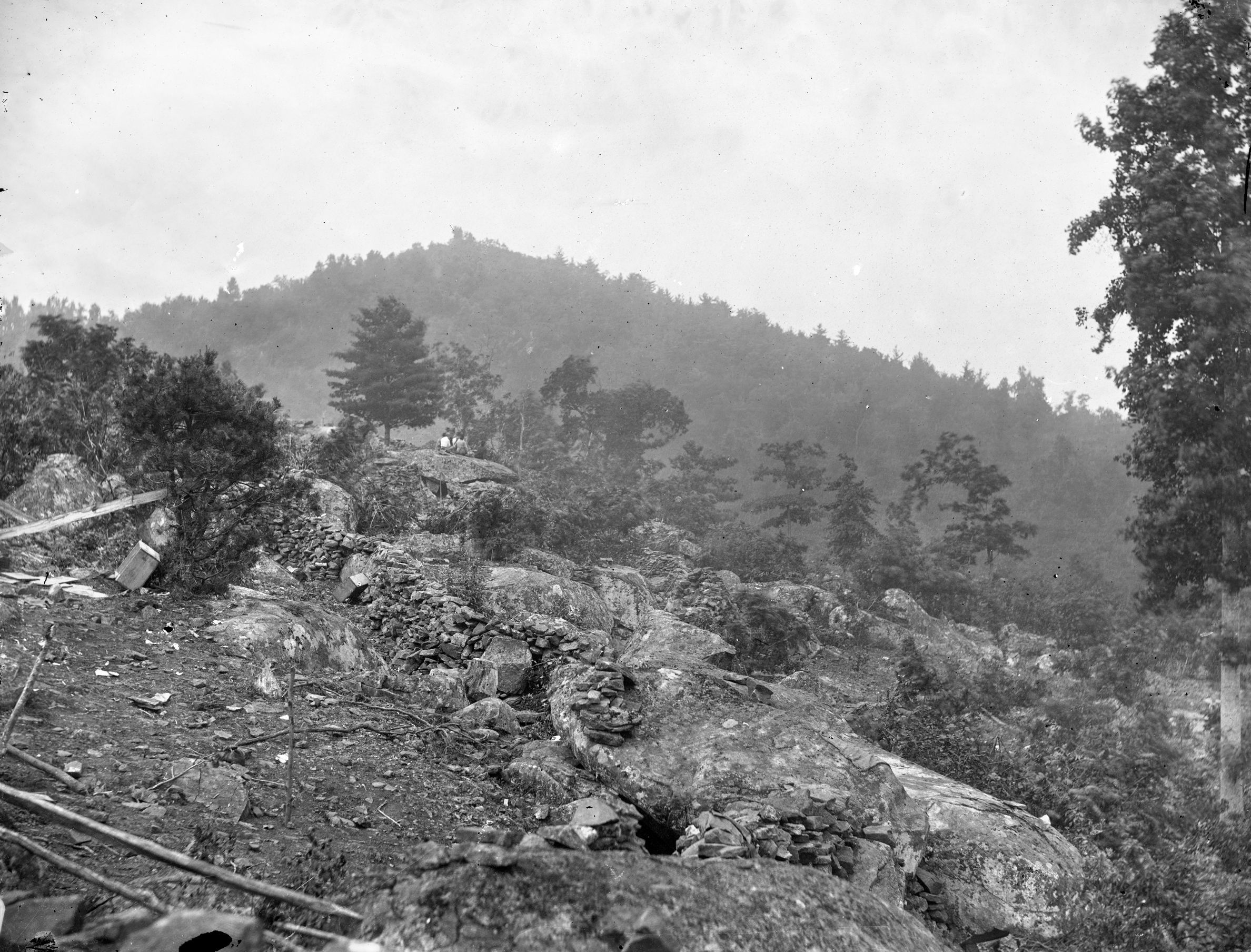

Covering the left flank of the Union Army at Gettysburg, the hill known as Little Round Top, was heroically defended against determined Confederate attack. As soon as Union commander General George Meade realized a Confederate attack on the Union left was immanent, he had Colonel Strong Vincent dispatch the four regiments of his brigade to defend the hill, including Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine.

As Chamberlain recalled later, “Passing to the southern slope of Little Round Top, Colonel Vincent indicated to me the ground my regiment was to occupy, informing me that this was the extreme left of our general line, and that a desperate attack was expected in order to turn that position, concluding by telling me I was to ‘hold that ground at all hazards.’ This was the last word I heard from him.”

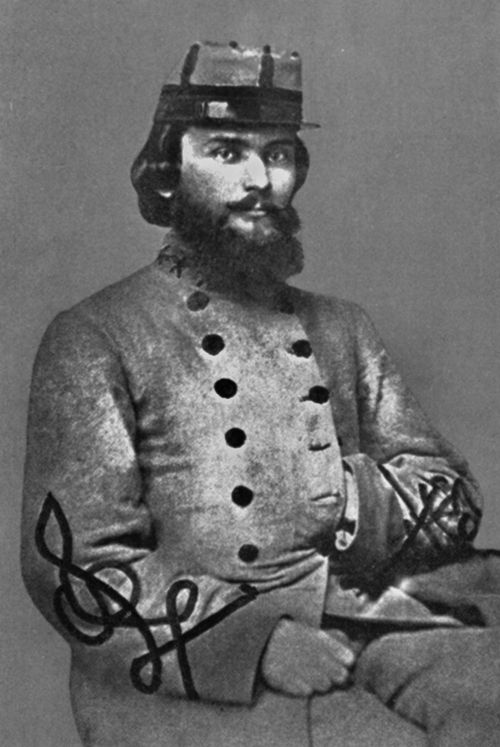

Facing the 20th Maine was the 15th Alabama Infantry, commanded by Colonel William C. Oates, a lawyer from Abbeville, Ala. Oates’s regiment, part of Law’s brigade of Hood’s division, had marched nearly the entire day, covering a distance of approximately 25 miles before arriving at Gettysburg. With movement from the enemy.

Once the attack began Oates’s riflemen found the going extremely difficult. “My men had to climb up, catching to the bushes and crawling over the immense boulders,” Oates wrote, “in the face of incessant fire of their enemy, who kept falling back, taking shelter and firing down upon us from behind the rocks and crags that covered the mountain side thicker than grave stones in a city cemetery.”

After repeated attempts, at various places, small groups of Confederates managed to breach the Federal perimeter. The combat surged backward and forward like a wave. As quickly as the Southern infantry was repulsed, Oates urged his men to move forward again. Flushed with renewed spirit, the gray clad riflemen momentarily dislodged Chamberlain’s men, but again were pushed back.

“We drove the Federals from their strong defensive position,” wrote Oates. “Five times they rallied and charged us—twice coming so near that some of my men had to use the bayonet—but vain was their effort.” With victory seemingly his, Oates realized reluctantly that his men’s tremendous drive could not be sustained. “The long blue lines of Federal infantry were coming down on my right and closing in on my rear,” he reported, “while some dismounted cavalry were closing the only avenue of escape on my left, and had driven in my skirmishers.”

Oates finally had to order a retreat. When he did, he and his men “ran like a herd of cattle.” Oates continued, “As we ran, a man named Keils who was to my right and rear had his throat cut and he ran past me breathing at his throat and the blood spattering. His windpipe was entirely severed.” Oates tried to reorganize his regiment atop Big Round Top, but any further effort to regroup was futile. Overcome with heat and exhaustion, Oates collapsed unconscious and had to be carried to the rear. The fighting on Little Round Top was over.

“There never were harder fighters than the 20th Maine and their gallant colonel,” William Oates said later. “[Chamberlain’s] skill and persistence and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top, and the Army of the Potomac, from defeat. Great events sometimes turn on comparatively small affairs.”

Joshua Chamberlain and his 20th Maine Regiment received numerous accolades in the years following the battle but his Confederate counterpart was given scant recognition. Perhaps part of the reason Oates never received the kind of recognition that Chamberlain has, was the difference in their social stations. Unlike the well-born Chamberlain, William Oates came from humble beginnings. Born on November 30, 1833, in Pike County, Ala., Oates spent his boyhood on his parents’ none-too-successful farm. He received little formal education and was primarily self-taught.

Like many of his neighbors, Oates led a wild frontier-like life. At the tender age of 17, he fled Alabama thinking he had beaten a man to death during a fight. Escaping to Texas, Oates continued his womanizing, brawling, and gambling, quickly earning a reputation as a tough customer. A few years later, Oates’s younger brother John tracked him down and asked him to return to Alabama—the man he thought he had killed was, in fact, very much alive. Oates agreed to return and settled down to a more serene lifestyle.

He became fascinated with the law and graduated from law school and successfully passed the Georgia and Alabama bar exams. With his brother also becoming an attorney, the pair opened up a law office in Abbeville, Ala. Soon, the two brothers were pillars of the community.

When the Southern states began to secede from the Union, Oates urged patience. However, after Alabama seceded, he put his law practice on hold and offered his services to the newly formed Confederate Army.

Obtaining the rank of captain, Oates formed his own unit, called the Henry Pioneers after the county where he resided. The company was reassigned to the 15th Alabama Regiment of Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s Brigade of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Alabamians subsequently saw action at the battles of Cross Keys, Gaines’s Mill, Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, Chantilly, Antietam, and Fredericksburg.

Promotion came easy for Oates, and within a short time he was a colonel, taking charge of the 15th Alabama in the spring of 1863. For some reason, the Confederate Congress failed to confirm the promotion, which technically meant that Oates never reached a rank higher than lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army. Nevertheless, he claimed for himself the rank of colonel for the remainder of his life.

Despite the debate over his promotion, Oates was in charge of the regiment on that fateful day in July at Little Round Top. He was grief-stricken at the loss of life from his regiment. “My dead and wounded were then greater in number than those still on duty,” he would later say. “Of 644 men and 42 officers, I had lost 343 men and 19 officers. The dead literally covered the ground. The blood stood in puddles on the rocks. The ground was soaked with the blood of as brave men as ever fell on the red field of battle.”

A few months later Oates was again surrounded in controversy. At the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, he ordered a South Carolina unit into the fight, despite the fact that he had no formal authorization to give such an order. The 15th Alabama was also blamed for a friendly fire incident, a charge that Oates vehemently denied. “There was no better regiment in the Confederate Army than the Fifteenth Alabama,” Oates maintained.

Despite these accusations, the regiment performed gallantly at Brown’s Ferry, Lookout Valley, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. Although a brave and courageous leader, Oates lost command of the regiment. He was later placed in charge of the 48th Georgia. Near Petersburg, Va., on August 16, 1864, he was struck in the right arm by a Union bullet. The wound was so severe that it required amputation. The war was over for William Oates.

With the end of the Civil War, Oates turned his attention to politics and served the state of Alabama in various positions. Capitalizing on his war fame, he used the campaign slogan “the one-armed hero of Henry County,” when running for office. His strategy worked and he was elected to Alabama’s House of Representatives for two years. He was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention and the state constitutional convention. In 1880, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from Alabama’s 3rd District. In 1894, Oates decided to try his hand at governorship. The election was a mudslinging event, ripe with doubledealing, dirty politics, and corrupt bargains. He won, but only served one term as governor.

During the Spanish American War, President William McKinley tapped Oates to head three different brigades during the brief war with Spain. Although never seeing combat, he served proudly. Realizing the irony in it, Oates joked “I am now a Yankee General, formerly a Rebel Colonel, and right each time!”

Politics aside, Oates still maintained his law practice in Montgomery and dabbled in real estate. These two occupations made him rich. Together with his wife and son, the old colonel visited Europe in 1902. William C. Oates, Jr., would also become a lawyer and a partner in his father’s law firm.

Despite his good fortune, the Civil War in general and Little Round Top in particular were indelibly etched in Oates’s memory. He was haunted by the death of so many fine citizens of his beloved state, especially his brother John. For several years he tried in vain to have a memorial erected on Little Round Top for the fallen soldiers of the Alabama units that fought there. The Gettysburg National Military Park commissioners continually denied his request. He would later write a book, The War Between the Union and the Confederacy, giving prominent mention to his regiment’s battles during the war.

Oates remained active in veteran’s affairs until his death on September 9, 1910, at the age of 78. He was laid to rest in Montgomery with full military honors. Oates was praised in the newspapers for his battlefield exploits and his dedicated service to his state and country after the war.

One newspaper captured the very essence of Oates’s life when it stated simply, “He was full of pluck!” He certainly was.

The reason Colonel Oates never got the publicity he deserved was that the South lost the battle and the war.