By Chuck Lyons

When still a young boy, Hannibal once came upon his father, the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca, who at the time was preparing to go to Iberia where Carthage was campaigning to expand its power. The boy begged to go along and join in the upcoming fighting. Hannibal’s father, the Roman historian Livy wrote, took the boy to a Carthaginian sacrificial chamber, held him up to a fire burning in the room, and made him swear that he would never be a friend of Rome.

“So soon as age will permit,” the boy supposedly answered, “I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome.”

After that, he was permitted to join his father’s campaign.

Young Hannibal was to grow into perhaps the greatest of Rome’s enemies. At Lake Trasimene in June 217 bc, Hannibal sprung what has been called “one of the largest and most successful ambushes in military history” after goading the impetuous Roman Consul Gaius Flaminius Nepos into battle.

In less than four hours, the Carthaginian general annihilated Flaminius’s Roman army. Livy wrote—with some embellishment—that the fighting was so severe that neither army was aware of an earthquake that at the very moment of the battle “overthrew large portions of many of the cities of Italy, turned rivers, and leveled mountains with an awful crash.”

In the course of the battle, Hannibal’s Carthaginians and their allies killed some 15,000 Roman legionnaires.

One of the largest engagements of the Second Punic War, Hannibal’s victory at Lake Trasimene helped cement his strategic reputation and for a time panicked the Roman people and Roman Senate.

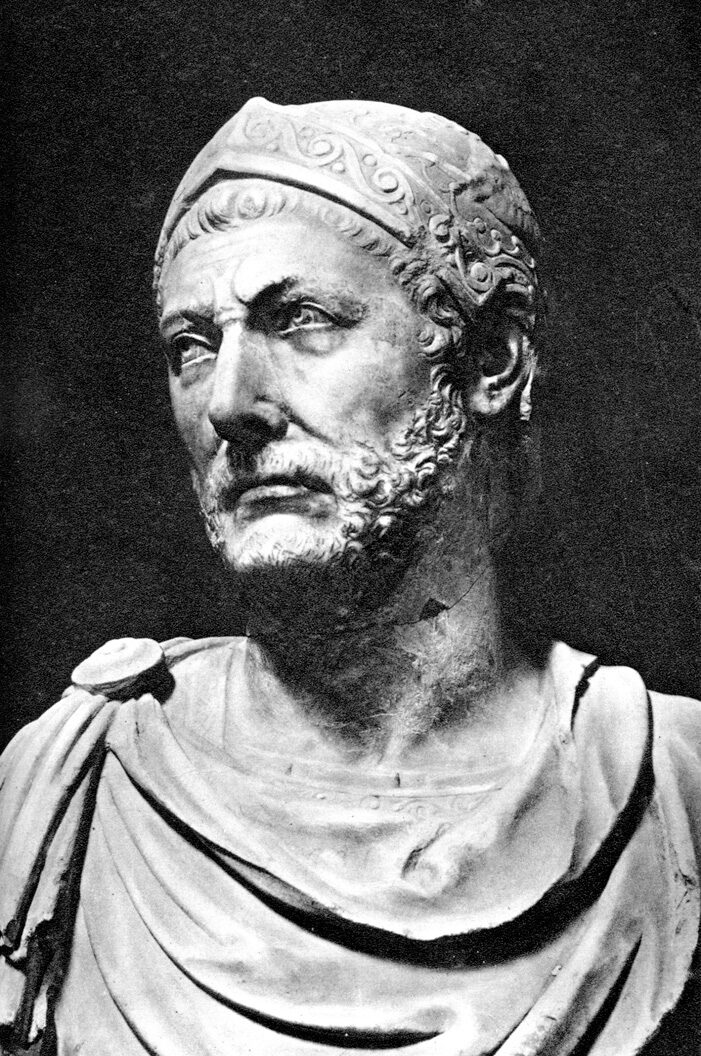

Largely because of Hannibal’s success there and because of his bold attack on the Roman heartland, which offered Carthage its best chance of success against the legions of Rome, history has come to regard Hannibal as one of the greatest military strategists of the ancient world, the equal of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. In modern times, no less a military man than the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte praised him, and he has in fact been called the “father of strategy.”

The three Punic Wars (called“punic” because of the Latin name for the Carthaginians,“Punici,” a reference to their Phoenician ancestry), were primarily a struggle between the city state of Carthage, located in what is today Tunisia, and Rome for supremacy in the western Mediterranean Sea. At the beginning of the decades-long conflict, Carthage was dominant, possessing territory all along the Mediterranean coast of Africa and in what is today Spain. In contrast, Roman power was still contained on the Italian Peninsula. By the end, Roman power stood alone and unchallenged.

The First Punic War erupted in 264 bc, when the two powers squared off over the island of Sicily at the toe of the Italian boot. Fighting continued for two decades until the Romans won a decisive naval victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 bc. Carthaginian naval power was largely destroyed, and Hamilcar Barca, then the Carthaginian commander in Sicily, was cut off and forced to negotiate a peace with Rome and evacuate Sicily.

Before the First Punic War, Rome had been largely a land-based power with no navy to speak of. The war against Carthage, then a great naval power, forced Rome to quickly build its own fleet and train its own naval force, a force that won the final and decisive battle of the war.

The end of the war left Rome the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean Sea. Carthage, meanwhile, was forced to begin paying a sizable indemnity to Rome.

Seeking to make up territorial losses from the war and with an eye on the plentiful silver of the Iberian Peninsula, which would aid in paying its indemnity, in 237 bc Carthaginian forces under the command of Hamilcar began expanding Carthage’s power there. Hamilcar himself drowned in battle against native Iberian tribes in 229 bc, but Carthaginian efforts to subdue the peninsula continued, the offensive culminating in the founding of New Carthage (the current Cartagena, Spain) on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast in 228 bc.

Hannibal, sometimes called Hannibal Barca, was born in 247 bc, one of at least six children of Hamilcar Barca, three daughters and three sons. He was the oldest of the sons. Historians have debated for centuries without resolving the question of whether “Barca,” which is translated as “thunderbolt,” was applied to Hamilcar alone or was a hereditary name within his family, and therefore also would be Hannibal’s.

When Hamilcar died in 229 bc, he was succeeded in command in Iberia by Hasdrubal the Fair, who was married to one of Hannibal’s sisters. When Hasdrubal in turn was assassinated in 221 bc, Hannibal, then 21 years old, was proclaimed the Carthaginian commander of Iberia.

He was welcomed joyously by the men who had campaigned under his father.

“The old soldiers,” Livy wrote about Hannibal’s rise to command, “fancied they saw Hamilcar in his youth given back to them; the same bright look; the same fire in his eye, the same trick of countenance and features. Never was one and the same spirit more skillful to meet opposition, to obey, or to command.”

Hannibal spent the next two years completing the Carthaginian conquest of Iberia.

Rome, meanwhile, fearing Carthage’s growing strength to their west, made an alliance with the fortified city of Saguntum on the Mediterannean coast of the Iberian Peninsula, a city that lay a considerable distance south of the River Ebro, and claimed the city as a Roman protectorate. Hannibal saw this action—as it was—as breaching a treaty that had been signed between Rome and Hasdrubal the Fair, a treaty that had established the Ebro as the boundary line between the territories of the two powers. Hannibal responded by laying siege to Saguntum in 219 bc, and the city fell to him eight months later after putting up a fierce defense.

Hannibal, motivated by a personal lust for glory and perhaps a need to avenge his father’s losses in the First Punic War, also remembered his boyhood oath and became determined to carry the war he had begun at Saguntum into the heart of Roman power. Hannibal was able to gain some limited support from the Carthage Senate, which at the time was controlled by a relatively pro-Roman faction that did not completely agree with his aggressive tactics on the Iberian Peninsula, and retired to New Carthage where he gathered his forces. Hannibal then took a brief religious pilgrimage, sent his Iberian bride and infant son back to Carthage, and in late spring 218 bc began his march against Rome.

The Second Punic War had begun.

His strategy, which had been originally developed by Hasdrubal the Fair (possibly even by Hamilcar) but never implemented, had sprung from the resounding Roman naval victories of the First Punic War. With their navy all but gone, Carthage would have to develop and rely on a land campaign to again attack Rome.

Hannibal hoped to open a northern front in Italy and then attack and subdue the Roman-allied city states of the Italian Peninsula one by one without directly attacking Rome itself. Such a strategy also was designed to keep the war away from Carthage. In addition, it would put the burden of sustaining the fight on the enemy’s lands.

Hannibal had undertaken his advance, the second-century Greek historian Polybius wrote, “with consummate judgement.” Before beginning his march, for example, Hannibal had sent men ahead to reconnoiter a route and attempt to gain safe passage and allies among the native tribes of northern Hispana and Gaul over whose territory he would have to pass.

Meanwhile, Rome had been doing just the opposite.

Perhaps lulled into a state of complacency by their earlier successes, the Roman people and the Roman Senate had allowed Carthage 20 years to regain its strength following the First Punic War and had all but ignored the Carthaginian buildup on the Iberian Peninsula. The Roman Senate appears to have believed it could put down any Carthaginian uprising at will, and while it pursued other matters it had allowed Hannibal to choose when and where a war would take place.

Rome was not prepared for the boldness of Hannibal’s expedition.

Polybius wrote that Hannibal originally headed north from Hispana with a force of 82,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 37 war elephants, but as is usually the case with ancient sources concerning the size of armies and of casualties, the numbers given are open to question. He fought his way through hostile tribes of northern Iberia and crossed the Pyrennees Mountains. Losses suffered in these struggles, which at times were heavy, along with the garrisons he had been forced to leave behind meant he may have crossed the Pyrenees with only about 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry, as well as the war elephants left in his army.

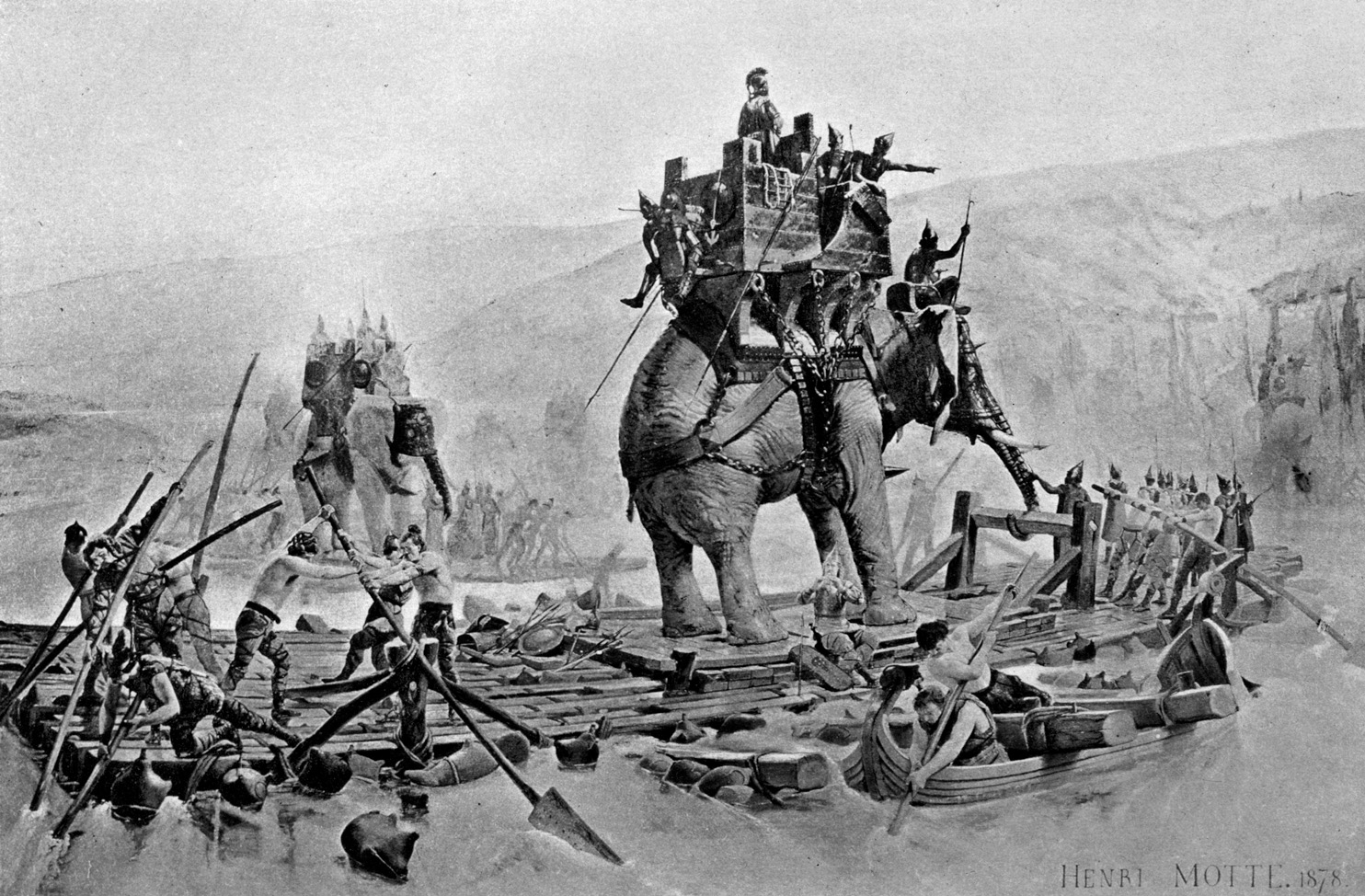

Hannibal marched across southeastern Gaul subduing the tribes that opposed him there and collecting allies from those willing to aid in the planned destruction of Rome. He evaded a strong Roman force marching against him from the Mediterranean by turning inland up the valley of the Rhone River and crossed the Rhone in the autumn of 218 bc, ferrying the elephants across on large earth-covered rafts. In October, Hannibal reached the foothills of the Alps.

Hannibal was able to cross the Alps’ already snowy passes by a route that has never been clearly established and that historians have debated since the time of Livy. He arrived in Italy with perhaps 38,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. According to Polybius, Hannibal arrived there accompanied by as few as 20,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 horsemen. Once in northern Italy, Hannibal’s army, bolstered by Gauls and Ligurians who had joined its ranks, first met serious Roman opposition near the Po River.

There in December 218 bc at the Trebia River, a Po tributary, the Carthaginians confronted a Roman force that may have been as many as 42,000 men, including 4,000 cavalry under Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus. Hannibal was able to wear down the Roman force and finally destroy it with a surprise attack from the flanks. Hannibal had won a sound victory on Italian soil.

Greatly distressed by the defeat at the Trebia, the Roman Senate ordered Sempronius back to Rome. In early 217 bc, two new consuls, Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius Nepos, were elected with Flaminius placed in command of what remained of Sempronius’s army. Servilius was named to the command of a second army. Four new legions were also raised and were divided between the two consuls, and Flaminius’s army turned south from the Po to prepare for a defense of the city of Rome itself.

Flaminius, a populist Roman politician and former governor of Sicily, had overseen the construction of the Circus Flaminius, a large arena and race track in Rome, and had also served militarily against the Gauls. Flaminius was a “new man,” being the first of his family ever to be elected a consul. He had developed a reputation for supporting small farmers and a reputation for impatience. After being named consul, he had left the city without performing the religious rituals required of a newly named consul and had in fact been recalled to Rome, a summons he had ignored.

Flaminius’s failure to properly honor the gods caused widespread anxiety in Rome, where it was feared Flaminius’s disrespect would bring disaster. Both Livy and Polybius describe him as man “of bold words and little talent who based a career on pandering to the desires of the poorest citizens.” Like Sempronius, he was said to be “impetuous, overconfident, and lacking in self-control.”

In the spring of 217 bc, Hannibal also moved, heading south into the Italian Peninsula where he could continue to pressure the Romans and provide his troops with food from the land they crossed. Both he and the Roman Senate were aware that there were two probable routes south. The Appenine Mountains run down the Italian Peninsula like a spine. Hannibal therefore could march to the east of the mountains or to the west. The Senate positioned Servilius and Flaminius and their armies with one blocking the eastern route south and one the western route.

With Roman armies waiting to intercept him as he moved south, Hannibal as usual did the unexpected. He found a third route.

He quickly crossed the mountains into Etruria, the area immediately to the north of Rome, and entered the marshes around the mouth of the Arno River, an area that happened to be overflowing even more than usual that particular season because of the winter’s rains. It was an area the Romans had considered impassable. Polybius claims Hannibal’s men marched for four days and three nights “through a land that was under water,” losing a number of men to the perils of the march. Besides the rigors of the march itself, the exhausted men had great difficulty finding any place to rest on the flooded ground and often were able to sleep only by lying on pack saddles or even on the corpses of the many pack mules that died during the crossing.

Hannibal was at the time suffering from conjunctivitis, a serious imflamation of the eye, which would eventually cost him sight in one eye. He had to be carried through the marsh on the expedition’s by then sole surviving elephant, a beast named named Surus,“The Syrian.”

The bulk of Hannibal’s elephants had probably perished crossing the Alps.

For centuries, historians have debated the source of these elephants. Even in ancient times, Indian elephants were believed to make better war elephants than their African cousins. If Hannibal had Indian elephants with his army, how did he get them? How had they made their way from India to the north of Africa? It is known that the Eypgtian armies took some such beasts as booty during a campaign in Syria. Consequently, Hannibal may have somehow acquired the descendants of those elephants from the Eypgtians. The fact that Hannibal’s last elephant was named “The Syrian” does lend some credence to that claim. It has also been suggested, however, that Hannibal’s elephants were a now extinct species of African elephant.

In either case, the elephants had been intended to frighten enemy troops with their imposing bulk and terrible bellows—an ancient form of psychological warfare.

Hannibal was getting close to the city of Rome itself, and by moving into Etruria he had fulfilled his vow to bring the war into the Roman heartland.

Believing correctly that Flaminius was rash and incautious, Hannibal began devastating the Eturian countryside, providing food and plunder for his men and hoping to lure Flaminius, the populist supporter of small farmers, into battle at a time and place of Hannibal’s choosing. In addition, it should be remembered that Hannibal had no base in Italy and no supply line. This gave his army considerable freedom of movement, but at the same time, since it was living off the land, it needed to keep moving.

Meanwhile, Servilius was also moving in an effort to combine his force with that of Flaminius.

“Flaminius became excited,” Polybius wrote, “and enraged at the idea that he was despised by the enemy: and as the devastation of the country went on, and he saw from the smoke that rose in every direction that the work of destruction was proceeding, he could not patiently endure the sight.”

He nonetheless at first avoided being goaded into battle and stayed in his camp as Hannibal marched around his left flank and effectively cut Flaminius off from Rome in what was probably the first recorded turning movement in military history.

The Romans had extensive experience fighting, but they were no match for Hannibal when it came to maneuvering.

Goaded by the burning of the countryside and fearful of the reaction of the Senate, Flaminius reacted as Hannibal had thought he would. He marched eastward against Hannibal. Impetuous as always, he was said to have ignored the advice of his advisers who wanted to send only a cavalry detachment to harass the Carthaginians and prevent them from laying waste to any more of the country.

But Flaminius ordered his entire force forward.

“Though every other person in the council advised safe rather than showy measures, urging that he should wait for his colleague, in order that joining their armies, they might carry on the war with united courage and counsels…. Flaminius, in a fury … gave out the signal for marching for battle,” Livy wrote. He also ignored what many considered some bad omens prior to marching. At one point, Faminius had been thrown from his horse, and at another Roman standard bearers had trouble freeing their standards from the mud where they had been placed upright.

The Romans moved east through the devastation Hannibal had wrought, Polybius wrote, swelled by enthusiastic volunteers who anticipated an easy Roman victory and carried chains with them to bind the prisoners they expected to take and to sell as slaves.

The scene was set for disaster.

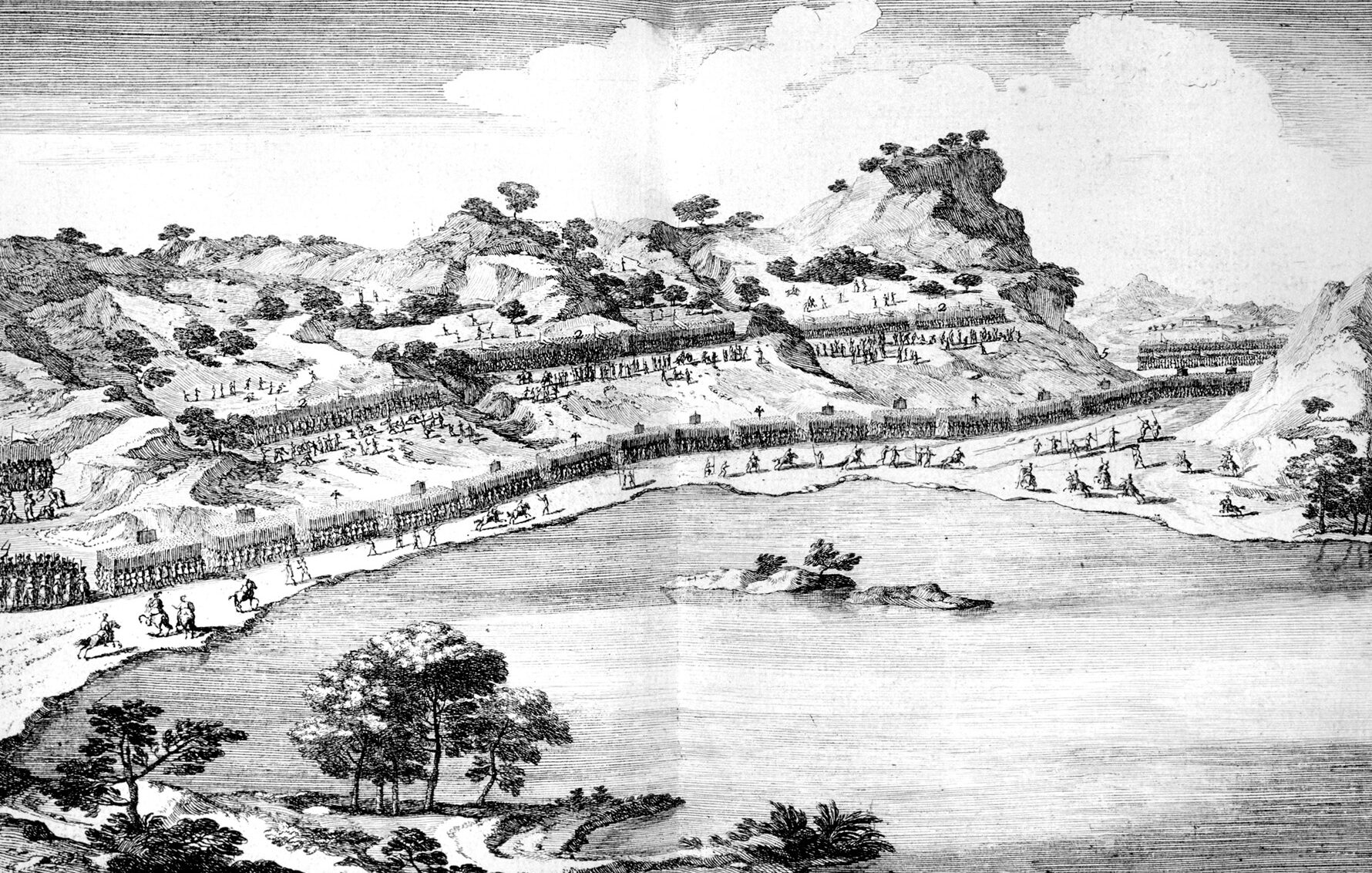

With the Romans less than a day behind him, Hannibal paused at a place near Lake Trasimene where the road passed along the north side of the lake through a defile and into a natural amphitheater that was perhaps five miles long and up to 11/2 miles wide. The lake itself is the largest lake on the Italian Peninsula. To the west of the plain was the defile and to the eastern end the hills came down almost to the shore of the lake.

Hannibal camped at the far eastern end of the plain and during the night marched his troops around behind the hills, placing most of them parallel to the road but hidden in the hills and woods, often on the reverse slopes. He placed his cavalry at the defile, and his archers and slingers were hidden at intervals overlooking the plain.

The skill of these Carthagian troops is clearly shown in their ability to move at night over such unfamiliar ground and yet arrive where they were supposed to. Hannibal also ordered his men to light campfires in the Carthaginian camp at the eastern end of the plain—at a considerable distance from his planned ambush—to help convince the Romans that his men were farther away than they actually were.

What was to occur was a rare—and perhaps the only—example in history of an ambush set with one entire army against another.

Secrecy was essential.

Interestingly enough, Hannibal was able to keep his plans secret despite the presence of the inhabitants in the region who might have been suspected to have reported Hannibal’s presence in the area to the Roman general.

On the morning of June 21, Flaminius broke camp early and headed east in fog. In what has been called “the usual Roman way,” he sent no scouts ahead to try to determine the location of the enemy or the nature of the ground.

That morning, Hannibal sent out a small skirmishing force that engaged the Roman vanguard and succeeded in pulling it away from the main Roman force. Convinced by these Carthaginian skirmishers that they were getting close to battle, the Roman army passed through the defile and when it entered the plain spread out in a more convenient marching order. In the distance, about four miles away, the tents of the Carthaginian army could be seen, and Flaminius, who was eager for battle, must have surmised the enemy was gathered there. As the head of the Roman column approached the eastern end of the amphitheater, it halted to close ranks before advancing on the Carthaginian camp, which was a short way beyond that spot.

Suddenly and without warning, Carthaginian trumpets blared, their blasts rippling along the hillsides, and Carthaginian cavalry swept down on the west sealing off the defile. The Carthaginian infantry, whose rigid discipline had held them quietly in place, began to pour down from the hills where they had hidden. In the fog, the Romans could see little of their attackers but could hear their war cries and the thuds of arrows and stones hurled into their midst.

There was no escape.

On one side was the lake and on the other the charging Carthaginians; to the Romans’ right and left, the narrow and blocked passages off the plain. The Roman forces did not have time to form up and were forced to fight were they stood and quickly split into three parts. They may have entered the plain in a three column formation; their actual marching formation is undetermined. There was panic and chaos among the troops. Centurions struggled to form what battle lines they could, not knowing in what direction to face them. To the west, where Hannibal’s cavalry had sealed off the defile, the horsemen continued to press the Roman column, forcing it back against the edge of the lake. The Roman center, including Flaminius himself, stood its ground as Hannibal’s Gallic allies hammered against it again and again.

The Roman soldier, who was all but unbeatable in the disciplined lines of his legion, here fought alone and was destroyed. For three hours the battle raged in the morning fog, legionnaires fighting together in small bands or plunging into the lake in an attempt to escape. Others killed themselves on the field rather than face the vengance of the charging Carthaginians.

Polybius writes that Flaminius panicked, while Livy credits him with behavior more fitting a Roman consul. He rode around the Roman army, Livy wrote, trying to encourage the men and organize some kind of resistance and shifting men to wherever he saw them needed. In either case, Flaminius in his distinctive consular dress was easily recognized by the enemy.

Eventually, as the fighting wore on a Gallic cavalryman, identified by Livy as a man named Ducarius, charged the Romans, carved his way through Flaminius’s bodyguard, and killed the consul with his spear. Livy says a group of legionnaires was able to drive the Gauls back sufficiently to rescue Flaminius’s body.

After the battle, however, Hannibal was said to have searched for the consul’s body to give it an honorable funeral but was unable to find it. Perhaps by then looters had stripped the body of its armor and other garments and it looked like just another dead legionnaire on a field of dead legionnaires.

So bitter was the fighting, Livy said, neither side was aware of a strong earthquake that hit the peninsula.

Organized resistance, what little of it there was, collapsed with the consul’s death.

Men fled into the lake and drowned or were hacked to death by Carthaginian cavalry that pursued them. Others died trying to swim across the lake, their armor pulling them down.

Only on the eastern end of the plain were the Romans able to escape the carnage. The Roman vanguard, which had been separated from the main army, had been able to fight its way into and through the narrow area between the lake and the hills on the eastern edge of the plain. There, finally able to realize the extent of the disaster behind them and unable to do anything to help, they took refuge in a nearby village.

In fewer than four hours, the Roman army had been annihilated.

Maharbal was sent to pursue the Roman vanguard, which had broken out of the trap. He surrounded it on a hill later that day and captured it. Both Livy and Polybius wrote that Maharbal, Hannibal’s cavalry commander, promised safe passage to these Romans if they would surrender their weapons and armor, which they did. Hannibal, however, sold them into slavery regardless of Maharbal’s promise. Another 10,000 or so of the Romans were able to escape the massacre and made their way back to Rome by various means. The captured Roman legionnaires were retained as prisoners of war while Hannibal sent those fighters who had taken part in the battle as allies of the Romans home without ransom or punishment.

“I come not,” he famously said, “to place a yoke on Italy, but to free her from the yoke of Rome.”

It was perhaps a noble gesture but also a calculated one intended to encourage more of the Italian city states to pull their allegiance from Rome and back him.

The battle at Lake Trasimene was up to that time the worst defeat ever suffered by a Roman army. The 40,000-man Roman army that had marched through the western defile and onto the lake plain had been utterly destroyed. An estimated 15,000 of those men had been killed while Hannibal lost only 2,500 men (some sources say 1,500 men), mainly among the Gauls fighting in the center. The Roman dead included 30 senior officers. Polybius wrote that another 15,000 Romans were captured.

Most of the blame for the disaster has been put on Flaminius, who walked blindly into the trap, but in his defense, Tacitus, the first and second century bc Roman historian, writes that Roman armies were used to meeting their foes in open battle on open plains and not accustomed to ruse or artifice. So Flaminius was acting in accord with his time and place by not suspecting the possibility of ambush. Livy in fact considered Hannibal’s use of ambush to be deceitful. Flaminius had been proceeding in “the usual Roman way.”

Historians have also remarked that the Roman soldier of the time should not be underrated regardless of the losses at Lake Trasimene. The Carthaginians had the great advantages of surprise and position, and they were more experienced soldiers having fought their way through Hispana and Gaul before entering Italy. Regardless of these advantages, 6,000 Romans were still able to fight their way free of the trap. In material and organization, the Romans had a clear edge. However, the advantage that the Carthaginian army had was that of a veteran army under a commander whose genius was unrivalled at the time.

In routing the Roman legions at Lake Trasimene, Hannibal had also won a vast store of military equipment and other booty, and after the battle many of his men were outfitted in Roman armor and helmets and were carrying Roman shields and weapons.

Hannibal had won a great victory.

After the battle, Hannibal camped to allow his men to rest and to bury his dead. But when he was informed that a force of 4,000 horsemen under Propraetor Cnaeus Centenius had been sent out from Servilius’s army to reinforce Flaminius and was unaware of what had happened, he dispatched Maharbal with cavalry to meet it. Centenius was quickly routed with half his men killed or wounded and the other half captured.

Hannibal had now disposed of the only force that could check his advance upon Rome, but he realized he was without siege engines and could not hope to take the capital without them. In addition, he knew the Romans kept the city well garrisoned and could call up numerous other troops in a short time. He was also realist enough to know much of his Italian success so far had been due to his cavalry. What use was cavalry when attacking a walled city?

Hannibal’s judgment—his ability to correctly assess what his army was capable of and what lay beyond its reach—came into play when he purposely avoided marching on Rome. His instinctively believed an attack on Rome itself would fail.

Hannibal instead continued ravaging central and southern Italy and encouraging Roman allies to revolt against Rome.

When news of the defeat at Lake Trasimene reached Rome it caused panic among the citizentry and the Senate, which decided a military dictator was needed. It was the first time since 249 bc that such a step had been taken. Normally, such a dictator would be appointed by one of the serving consuls, but with Flaminius dead and Servilius still tied up in the field an election was held and Quintus Fabius Maximus was named dictator. Fabius, who was then 58 years of age, old for a Roman general of the time, had already served twice as consul and was to emerge as one of the greatest generals of the war and to hold the consulship three more times in the next decade.

Fabius quickly initiated a strategy of avoiding pitched battles with the Carthaginians in favor of a war of attrition aimed at wearing down the invader while Rome rebuilt its military strength. Such a strategic approach has come to be known as the “Fabian strategy.” The strategy usually relies on skirmishing and harassing the enemy, cutting its supply lines if they exist, and a general wearing away of the enemy’s morale and will to fight. It is generally employed when the belligerent adopting it believes it has time on its side.

History has generally regarded Fabius and his Fabian strategy as what saved Rome from defeat. It gave the city time to recover from Lake Trasimene and time to rebuild its strength.

Fabius earned the nickname Cuncato, the Delayer.

Hannibal was left largely free to ravage the Italian Peninsula for the year of Fabius’s dictatorship, harrassed by Roman troops but escaping any major confrontations. When Fabius’s dictatorship ended, the Roman people elected Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro as consuls. They abandoned the Fabian strategy and met Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae fought August 2, 216 bc. Some 86,000 Roman troops confronted 50,000 of Hannibal’s Carthaginians. The Romans were caught in a pincer movement, or double envelopment, and all but annihilated.

Hannibal occupied much of Italy for the next 15 years until Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus decisively defeated the Carthaginians in Spain and landed an army in North Africa. Hannibal was recalled to defend his home city and was defeated by Scipio at the Battle of Zama in October 202 bc. The war was over. Carthage ceased to be a major power, ceded to Rome its lands in Spain and those Mediterranean islands it controlled, and agreed to pay Rome an indemnity. By the time it was over, it was said the Second Punic War had involved about three-quarters of the population of the entire Punic-Greco-Roman world and that virtually every family in Rome lost a member in the destruction brought down on Italy by Hannibal.

After the war, Carthage struggled to pay the indemnities Rome had leveled against it and began to recover from its losses. Cato the Elder, a Roman statesman sent on a mission to Carthage in 175 bc, was shocked at the progress the city was making in its recovery and came to believe if left unchecked it would soon be strong enough to again challenge Rome for supremacy. Thereafter, he worked to rally Senatorial opinion against Carthage and ended every speech in the Senate regardless of its topic with the line: “Besides, I think that Carthage must be destroyed.”

Rome began looking for a provocation that would allow it to again go to war with the African city.

Meanwhile, Carthaginian territory was being usurped by its African neighbors while its treaty with Rome forbade it declaring any war without Rome’s permission—something that was consistently denied. When Carthage made the last of its indemnity payments, however, it felt free of the treaty that had bound it and declared war on Numbia without Roman permission.

Rome had the provocation it had been searching for.

Rome declared war on Carthage in 148 bc, and the Third (and final) Punic War began. The city of Carthage was attacked and put under siege. For three years Carthage withstood the Roman aggression until a force under the command of Scipio Africanus’s son, Scipio the Younger, overran the walls. After the city had fallen, Scipio sent to the Senate for final instructions and was told that the city of Carthage as well as all of those who had stood with it in opposing Rome were to be destroyed and their fields plowed and sowed with salt so nothing could grow there again. A formal curse was also laid upon anyone who would ever attempt to build upon the site where Carthage had stood.

For 17 days fires consumed the city.

Carthage had ceased to exist, and its territory became the Roman province of Africa.

The destruction of Carthage ranks among the most devastating final chapters of a conflict in history. From the ashes of Carthage, Rome laid the foundation for its commercial and naval superiority. The future of the Mediterranean in the centuries to follow would be directly tied to Rome.

Hannibal’s invasion of Italy 70 years earlier had been Carthage’s last, best chance, and it had failed. With it, the fate of the Mediterranean—and of the ancient world—was determined. Mercifully, Hannibal had not lived to see his city’s final destruction. After his defeat at Zama, Hannibal had remained in Carthage and been elected to political office. There he was able to enact some political and financial reforms intended to pay the war indemnity imposed by Rome.

His reforms, however, were unpopular with the Carthaginian people and, with opposition mounting against him, he finally was forced to flee the city and go into exile. He took positions as a military adviser with various powers—usually fighting against the Romans. Finally, after being betrayed to Rome, he committed suicide by poisoning himself at Bithynia in Asia Minor rather than falling into the hands of the city he had sworn to “use fire and steel to arrest.”

The year of his death is uncertain, but it was probably about 182 bc, 40 or so years before the destruction of Carthage.

The glory of Lake Trasimene, perhaps Hannibal’s greatest day, was gone.

Livy wrote that Hannibal, in calling for the poison that killed him, summed up the situation perhaps better than even he knew.

“Let us relieve the Romans of the anxiety they have so long experienced,” he is quoted as having said, referring to himself. The phrase could just as easily have been applied to Carthage itself.

Rome’s anxiety over both the city and the man had ended.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments