By Michael D. Hull

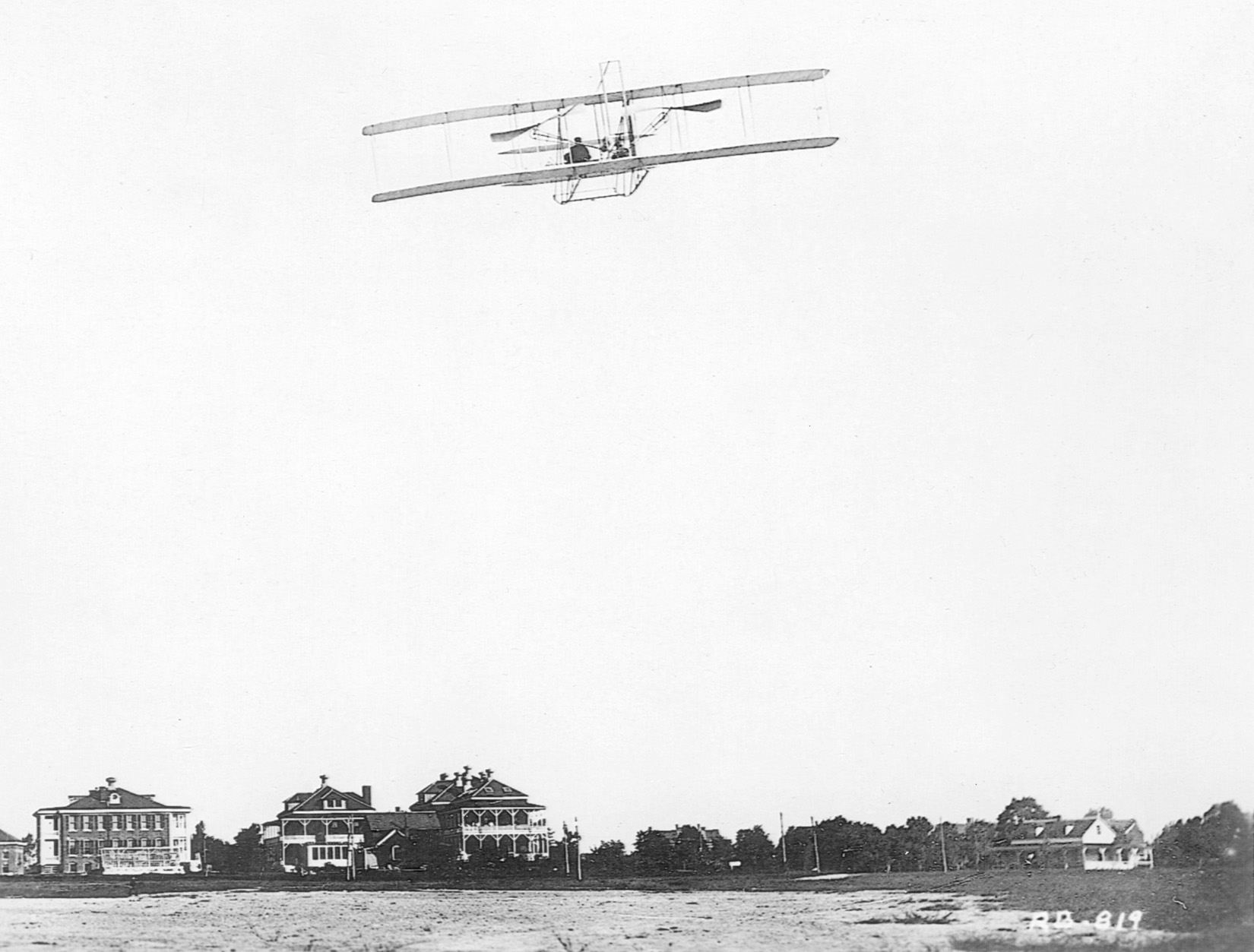

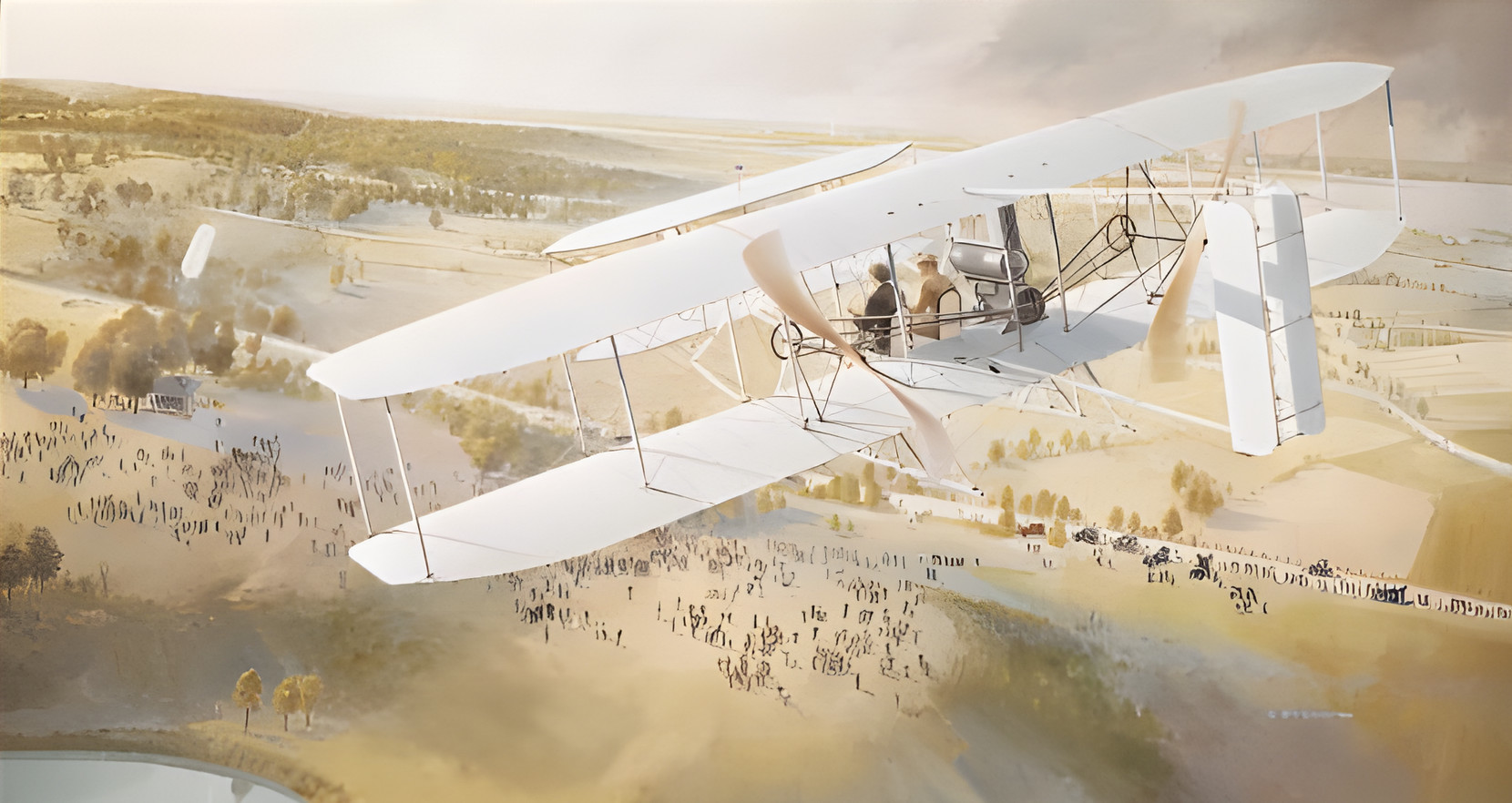

Resembling a “collection of bamboo poles more or less indefinitely attached to a gasoline engine,” the U.S. Army’s first airplane stood on the parade ground at Fort Myer, Va., on a warm and windless day in 1909.

The 25-horsepower engine that powered a pair of chain-driven propellers hacked and sputtered into life. The props turned, and the ungainly craft lurched along the parade ground and into the air.

It flew serenely to the small city of Alexandria, turned around, and returned to Fort Myer. Two men clambered down, elatedly compared notes, and shook hands.

One of the men, Aeroplane No. 1’s designer and pilot, was named Orville Wright. His objective was to sell the plane to the Army. The other man, whose job as official observer on the short flight was to convince the Army of the plane’s performance, was a scrappy little Army lieutenant from Washington, Conn., named Benjamin Delahauf Foulois.

In that brief flight, the two men set three world records: speed (42.5 miles an hour), distance (10 miles), and altitude (400 feet). The Army paid the Wright brothers $25,000 for the aircraft, plus a $5,000 bonus. Now all the new air service needed was a pilot, and Foulois was to be it.

The Army’s first flier was ordered to take the plane to Texas. His orders were simple. General James Allen, chief Army signal officer, told Foulois, “You are to evaluate the airplane. Just take plenty of spare parts and teach yourself to fly.”

The young lieutenant received a $150 voucher for funds to buy parts. This was America’s first air force budget, and it was earmarked for one year’s maintenance.

After arriving in San Antonio on the morning of February 5, 1910, Foulois spent much of his time at Fort Sam Houston that spring writing to Orville Wright for advice on basic aerial maneuvers. As Foulois liked to tell people later, he was the only pilot in history who learned to fly by correspondence course.

It was a modest start for the organization that, in his lifetime, would grow into the largest air force in the world, and a humble beginning for the man who was to do more to bring that about than any other.

When he died on April 25, 1967, the U.S. Air Force described Foulois as “the living link until now between the age of the Wright brothers and today’s astronauts,” and sent a flight of jet fighters in “missing-man” formation with one plane missing—the final salute to a fallen leader—streaking over his tiny hometown in northwestern Connecticut.

The lieutenant’s first solo flight at Fort Sam Houston was undertaken on March 2, 1910. “It was my first solo flight, first takeoff, first landing, and first crackup,” he wryly reported in his logbook. “I knocked the whole tail off. I wasn’t injured, but I learned to stick the nose down and stay with the ship. I was flying again a week later.”

With virtually no assistance aside from Wright’s letters, Benny Foulois stuck gallantly with his dangerous new profession. He compiled an impressive list of “firsts” in the early years of American military aviation. Besides being the first observer on a cross-country flight and the first military man to teach himself to fly, he made the first flight as a dirigible pilot in 1908; was the first to fly a plane more than 100 miles nonstop (1911); was the first to use a radio in flight (1911); was the first commander of a tactical air unit, the 1st Aero Squadron (1914); was the first to use an aircraft in combat, in Mexico in 1916; was the first chief of the American Expeditionary Force’s Air Service in 1918; and was the first chief of the Air Corps who was also a military aviator (1931).

The son of a Paris-born plumber who had served in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 and a Boston-born nurse, Benjamin Foulois was born on December 9, 1879. His parents lived in Pittsfield, Mass., before moving south of the state line to Washington. There Benny’s father started a plumbing business.

The boy learned reading and writing in a one-room schoolhouse, but he preferred fishing, baseball, and bicycle riding to schooling. He loved to stalk animals and was fascinated with birds. He would spend hours lying in the Litchfield County woods on summer afternoons, asking himself over and over, “Why can’t man fly? People are supposed to be smarter than birds, and yet we can’t get ourselves off the ground.”

He stayed in school for 10 years, and then his father asked him if he wanted to continue his schooling or go into plumbing. The boy liked books, but the business was thriving, so he decided to become an apprentice to his father. He learned well, but after about a year he grew restless to see something of the world.

After the sinking of the battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, Benjamin tried to enlist in the Navy at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. But he was turned down.

That April, however, the Cuba situation worsened, and President McKinley declared war on Spain. American ships were sent to blockade Cuba, and Congress issued calls for volunteers for the Army and Navy. This time, Benjamin was sure the Navy would take him, so, on a quiet Sunday morning in May 1898, he slipped his older brother’s birth certificate into his jacket pocket and bicycled all the way to Jersey City. He hiked to the Brooklyn Navy Yard the next day, but again was turned down.

He tried to find a job, but no one would hire him. Then, Benny happened to pass an Army recruiting station where men were being sought for the lst Volunteer Engineers. He stepped inside to inquire and, 15 minutes later and much to his surprise, found himself in the U.S. Army.

At Camp Townsend near Peekskill, NY, Benjamin was made a lance corporal and underwent a month’s training in building bridges, revetments, roads, and fortifications. That year, his unit sailed for Puerto Rico. This was supposed to be a major campaign, but the Spanish-American War was winding down after the capture of Santiago harbor and the surrender of the Spanish fleet. There were only a few skirmishes in Puerto Rico, and by August 12 word was received that an armistice had been signed. Benny’s unit labored at constructing bridges and roads, with its numbers steadily reduced by the diseases that ravaged the island. After seven months, with only two out of 40 non-commissioned officers in the regiment still on their feet, the American Engineers sailed home in January 1899. Benny credited rum, quinine, and self-discipline for his survival.

After a short leave at home in Washington, with the family doctor prescribing beer and cold baths to help Benny get rid of the quinine shakes, he went to New York and was mustered out of the service. He was sick of Army life. But Washington seemed to have shrunk and grown even quieter, and he grew restless again. He forgot about the discomforts of Puerto Rico and yearned for the discipline and camaraderie of the service. All appointments to the U.S. Military Academy had been made for the year 1899-1900, but Benny learned that a company of Regulars was being formed for service in the Philippines. With his parents’ consent this time, he rode a train to Camp Meade, Pa., and was sworn into G Company of the 19th Infantry Regiment.

After several months of patrolling and skirmishing against Filipino insurgents in Manila and on the islands of Panay and Cebu, Foulois’s regiment was ordered to undertake a campaign of “civic action.” The United States was trying to end the fighting and set the Philippines on the path to self-government. The Americans set up schools for the villagers, and one day Foulois’s top sergeant told him that he was now a schoolteacher. Protests that he himself had never finished school were to no avail, and for the next eight months he taught English, geography, history, and current affairs to Filipino children.

After a stint as first sergeant, he learned to his great surprise that he had passed an earlier examination and been added to the second lieutenants’ list. In September 1901, he was ordered to the island of Cottabato for civil government service. He was now the commanding officer of D Company of the 17th Infantry Regiment.

There was a growing prevalence of venereal disease among his men, so he had an old Spanish convent renovated as a clean, policed brothel, and Japanese girls were imported. No new cases of syphilis were reported.

One day in the spring of 1902, a fire broke out in the girls’ quarters. One of Lieutenant Foulois’s 10 jobs as commanding officer was fire chief, so he dashed to the scene and organized a bucket brigade. While Benny was on the roof, one of his hands was burned. Whenever he was asked later in life how his hand had become scarred, Foulois would truthfully answer, “In a government whorehouse fire in the Philippines in 1902.” He would get no second questions along those lines.

Foulois took part in 22 engagements against insurgents in the Philippines. In the summer of 1905, after service on the American West Coast and another hitch in the islands, Foulois reported for duty at the Infantry and Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth, Kans. He attended the Signal School and began to grow interested in aviation. By 1908, he had wangled his first assignment as an airman in dirigibles. A treatise he had written on the possible strategic and tactical value of airplanes won him the chance to ride with Orville Wright in 1909, and led to his appointment as the Army’s first pilot.

At Fort Sam Houston, with his single airplane and eight privates under his command, Foulois established the “Army Air Force.” They were hard times, and Lieutenant Foulois was forced often to reach into his own pocket to purchase such refinements as wheels to replace the skids on the nation’s first military plane. He also financed, from his own limited funds, the installation of safety belts as standard equipment aboard military aircraft.

He started experimenting with aircraft radios in 1910, and the following year built a set that he used while patrolling the Mexican border. By 1914, with the outbreak of war in Europe, the U.S. government began to take a more serious interest in air power. In 1915, newly promoted Captain Foulois was named commander of the lst Aero Squadron—America’s first air combat unit. He led the eight-plane fleet from Fort Sill, Okla., to San Antonio to fly reconnaissance along the Texas-Mexico border.

Foulois’s fledgling air corps served with distinction during General John J. Pershing’s punitive expedition into Mexico in 1916. The rebel leader, Pancho Villa, eluded the American force, and Foulois said later that if he had been equipped with higher flying aircraft he could have tracked down Pershing’s quarry. The general himself said that one airplane was worth a regiment of cavalry to him in Mexico.

Foulois was promoted to major in June 1917 and temporary brigadier general—the youngest in the Army at the age of 38—a month later. In 1918, he was appointed commander of the Air Service of the American Expeditionary Force sent to France. He personally led the first all-American squadron that was engaged in dogfights over the German lines. He organized his 412-man staff along French patterns on the Western Front. There was much to do because, as he said later, “Although I had expected some lack of organization, I was not mentally prepared for complete chaos when it came to the Air Service.”

He recalled, “Little did I realize that my team would have to fight Captain Billy Mitchell (the flamboyant, outspoken U.S. military observer in France at the time, and with whom Foulois locked horns for most of his career), the Army General Staff, the U.S. Navy, the British, the French, and the Italians before we would ever get to fight the Germans.”

For his gallant and tireless leadership in France, Foulois was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and the French Commander of the Legion of Honor. During the postwar years, he served as U.S. air attaché in Berlin, and in 1925 he took command of Mitchel Field on Long Island, NY. In 1927, he was appointed assistant chief of the Air Corps under General Mason M. Patrick. By then, the Air Corps had become an integral factor in America’s military establishment.

Foulois commanded the massive Air Corps maneuvers in 1931, in which 672 fighters, transports, and hospital planes participated. More than four million miles of massed maneuvers, cross-country missions, and solo flights were flown without a single fatality. One Sunday afternoon during the maneuvers, Foulois flew alone to his Connecticut hometown and landed in a pasture. While his planes roared overhead to impress New Englanders with the muscle of American air power, Benny stood in the pasture and chatted with boyhood friends.

In December 1931, he received his second star as major general, and replaced retiring Maj. Gen. James E. Fechet as chief of the Air Corps. The tough little plumber’s son who had started out as the Army’s first airman was now its top airman.

His four years as chief were marked by expansion, but also by tortuous and bitter wrangling with Congress. The nation was mired in the Great Depression, and Congress kept a tight lid on defense spending. Foulois said later that the difficulties he had encountered in the Spanish-American War, in Mexico, and in France were nothing compared with his war on Capitol Hill.

Foulois struggled for a larger budget for the Air Corps, for more benefits for pilots, and for better aircraft. It was a long, hard battle because in peacetime the Air Corps did not have the benefit of good public relations. While its personnel strength was only 10 percent of the total Army complement, the Corps had 37.7 percent of the peacetime fatalities.

Foulois approved the purchase of the Douglas B-18 bomber, the forerunner of a bombardment series that would eventually establish American air power. He also approved an order for the production of 13 B-17 Flying Fortresses, though he had no way of knowing that these would be the only four-engine bombers in the hands of the U.S. Army Air Corps on September 1, 1939, the day that Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring unleashed his Stuka dive-bombers on Poland to trigger World War II.

General Foulois faced the biggest and most heart-rending challenge of his career in February 1934, when, after a national uproar over corruption in the granting of airmail contracts to private airlines, the Air Corps was ordered to undertake the hauling of airmail. Foulois agreed, provided that President Franklin D. Roosevelt give the Air Corps both moral and material support.

With characteristic thoroughness and organizational skill, Foulois set up mail routes and pressed more pilots and planes into service. Aircraft were stripped of unnecessary equipment to make way for bulk mail, and bomb bays were sealed. But there was opposition from the start. Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s leading air ace of World War I, told the press, “Either they are going to pile up ships all the way across the continent, or they are not going to fly the mail on schedule.”

Without the improved aircraft for which Foulois pleaded long and hard, it was virtually a losing battle. Pilots struggled aloft in all kinds of weather, sometimes in open cockpits and always without deicing equipment. The crashes began to mount. Three airmail pilots crashed in one night during winter storms. The Roosevelt administration was accused by the press, the Republicans, and the public of “legalized murder,” and reporters admitted to General Foulois that they had orders to “get” him. The fact that the Air Corps planes were inadequate was considered his fault.

Eventually, in March 1934, Foulois and General Douglas A. MacArthur, Army chief of staff, were summoned to the White House. A scowling FDR asked Foulois, “General, when are these airmail killings going to stop?” Foulois replied simply, “Only when airplanes stop flying, Mr. President.” Roosevelt demanded that he investigate the airmail accidents and, Foulois later recalled, “for the next 10 minutes, MacArthur and I received a tongue-lashing which I put down in my book as the worst I ever received in all my military service.” Foulois later suspected that Roosevelt was more concerned with criticism of his administration than the deaths of Army pilots.

The airmail routes were phased down in the spring of 1934, and the last pouch was delivered by an Air Corps flier on June 1. The great experiment had failed, although Foulois had worked tirelessly to make it work. “We closed the books on a tragic but vitally important chapter in the history of American military aviation,” he noted.

A campaign spearheaded by Representative Hamilton Fish of New York pressured Foulois and Postmaster-General James Farley to resign. The opposition Republicans called for the enlargement and improvement of the Air Corps, and the villain ironically was Foulois. He was accused of profiting from airplane contracts and was “tried” by a House subcommittee. Then, reporters discovered that the panel had conducted secret sessions and had refused to publicize transcripts, so Foulois now found himself being defended by the press. He drew support from American Legion posts and civic groups all over the country, but the subcommittee retaliated by insinuating to Secretary of War George H. Dern that unless Foulois were relieved he could expect no additional funds for the expansion of the Air Corps.

After more bitter wrangling and considerable self-debate, Benny Foulois requested—and was granted—a three-month leave of absence in the fall of 1935, expiring a few days before the completion of his four-year tour as Air Corps chief.

He would then retire and pass on the struggle to his successor. He cleaned out his desk in Washington, DC, on December 31, 1935, and without fanfare boarded a train for Atlantic City, NJ, where his wife, Elisabeth, was waiting.

Foulois’s active military career was over, and he did not find it easy to change from uniform to mufti. He was 56 years old and healthy.

The couple lived quietly in a frame house near the ocean at Ventnor, NJ, from 1935 to 1958. Elizabeth became seriously ill, and was admitted to Andrews Air Force Base Hospital in Maryland. Knowing that she would never leave the hospital, the devoted Benny Foulois sold their house and moved to the visiting officers’ quarters on the base. She died in 1961.

Still smoking his favorite briar pipe, Foulois stayed energetic in retirement. He started writing a book, played competitive squash, and gave dozens of speeches every year as president of the Air Force Historical Foundation. He continued to take a close interest in air power, and was inducted into the Primus Club, a group of aerospace pioneers.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Foulois, then 62, went to the War Department and asked for a job. He was offered a desk job, but turned it down and went back to New Jersey to organize the state’s Civil Defense system.

In 1961, the U.S. Senate adopted a resolution authorizing the presentation of a belated Distinguished Flying Cross to Foulois. It was sponsored by Senator Barry Goldwater (R.-Ariz.), who told his colleagues that the tough little Nutmeg Stater “has the distinction of being the officer placed in charge of the first airplane owned and used by the Army.” On the eve of his 85th birthday, Foulois was honored at a dinner hosted by General Bernard A. Schriever, commander of the Air Force Systems Command, and attended by such famous airmen as General Carl A. Spaatz, first Air Force chief of staff; General Nathan E. Twining, former chief of staff; and Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, second commander of the Eighth Air Force in World War II.

General Foulois was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio in 1963.

After checking into Andrews AFB Hospital in the autumn of 1966, Benny Foulois suffered a heart attack that left him paralyzed and speechless. He never recovered, though he tried to communicate with visitors, and his only sign of recognition was a hand squeeze. His stout heart gave out on April 25, 1967.

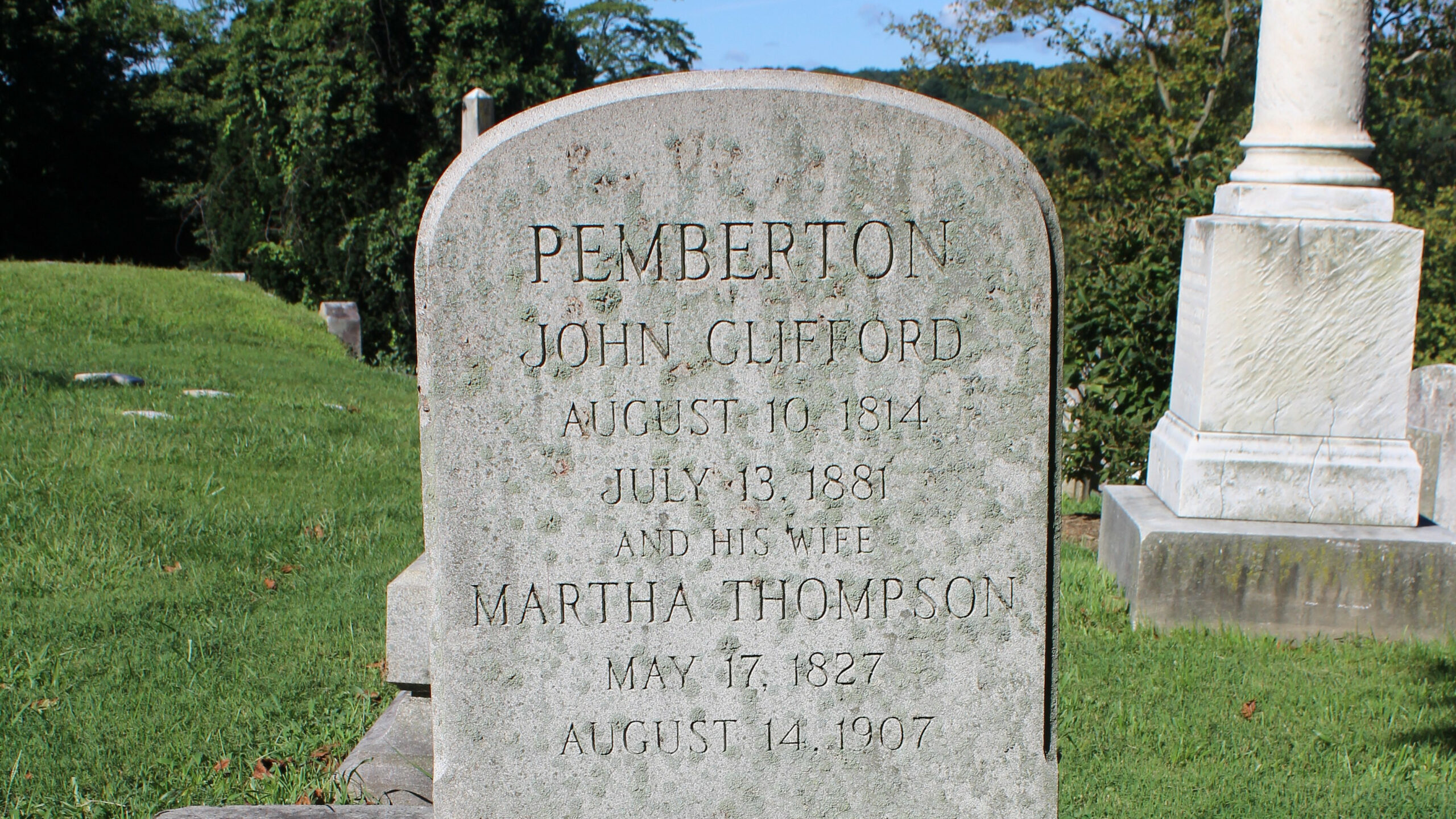

Full military honors were accorded him in proud Washington, Conn. Six colonels acted as pallbearers, a volley was fired by an Air Force rifle squad, taps was blown by a bugler, and a formation of F-191 Voodoo jets from the Suffolk County AFB on Long Island streaked overhead in the “missing-man” grouping.

First Selectman Roderick Wyant declared, “Washington is proud of our general and his accomplishments.” Foulois was buried in Washington Green Cemetery a short distance from his family’s plot.

Benjamin Foulois left an awesome legacy. No other man laid as much groundwork for American air power to help defeat the Axis Powers and defend the peace afterward. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments