By Susan Ludmer-Gliebe

In the autumn of 1495, three years after the Christian reconquest of Islamic Spain, Queen Isabella I of Castile and her husband, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, sent a letter to their master architect. “You will immediately depart for Salses,” they instructed him. “You must expressly examine the town to see whether it may be fortified to make it a good stronghold.”

Looking at Salses today, visitors can easily understand why the Catholic monarchs penned such a command. Sitting on a narrow strip of land overlooking salt lagoons and the Mediterranean Sea on one side and the Corbiere hills and nearby Pyrenees Mountains on the other, Salses straddles an often disputed and recurrently shifting frontier between Spain and France, two of Europe’s most dominant powers.

The Spanish royals were not the first to recognize Salses’s evident strategic position. In Roman times, a small castrum, or fortified encampment, called Salsulae was built abutting the Via Domitia, the military road linking Rome and Cadiz in southern Spain. Today, only small vestiges of the castrum remain, lying scattered amid wild almond trees, but the name has remained.

The Fortress of Salses: Masterpiece of Francisco Ramiro Lopez

Isabella and Ferdinand’s demand was in direct response to events developing across the sea on the Italian Peninsula, which had possible repercussions on the Iberian Peninsula as well. With the death of King Ferrante of Naples a year earlier, the French crown asserted its right to much of southern Italy, initiating with the Battle of Fornovo the first chapter in what became known as the Italian Wars. Soon after the victorious French monarch Charles VIII entered Naples in October 1495, the Spanish monarchs responded with their own military efforts to interfere with France’s imperial ambitions by dividing its attention. In addition to sending troops to Italy, Spain would amass large armies on each end of the Pyrenees, the Basque region to the west, and the Roussillon plains in the northern part of Catalonia to the east. They would dare France to respond.

The fortification of Salses played a key role in Spanish thinking as a base for future attacks and as a defensive barrier to their powerful neighbor to the north. As a result of the Spanish monarchs’ direct involvement, Spain reorganized and modernized its military, most importantly by establishing a standing army that would become a keystone to the nation’s military supremacy during the 16th century. At Salses, the logical methods applied to the battlefields were affirmed and copied. The actual building of the fort was run on a strict military basis, even though the craftsmen who built its walls, carved its doors, and tiled its floors were civilians.

Construction of the fort, an unusual blend of Moorish and Castilian architectural elements, began in June 1497 and cost a substantial 43,725 maradevis—about 116,601 gold ducats—in an age in which a worker earned about 15-20 maradevis a day. By any measure, the resulting structure was enormously impressive, as even a cursory walk around its perimeter walls, stretching more than a mile, will attest. It was one of the largest forts of its time.

“We know exactly how many nails, how many bricks were used and how much they cost,” explains Jean-Michele Pheline, administrator of the fortress. “We know that the ironwork came from the forges at Arles-sur-Tech, that the local limestone was milled at Armentera and then transported by boat or cart to the site, and that most of the wooden handles for the various imported metallic tools were locally made.” Even the smallest details of quotidian life are known, including a list itemizing the fort’s larder. When, for example, the French attacked in 1503, there were exactly 400 sides of salt mutton in storage. These very specific details are known because 10,000 primary documents from the reign of Isabella and Ferdinand have survived in the national archives of Castile.

Yet until recently, various guidebooks to the fortress wrongly identified the master architect who built Salses. Throughout their official correspondence, the Spanish monarchs used the salutation “Master Ramero” when writing or referring to their architect. For years it was assumed that “Ramero” referred to one Francisco Ramirez of Madrid. Ramirez was a great expert on artillery and served the crown as a secretary. But he did not build Salses, although he was coincidentally an acquaintance of the man who did.

By trawling through previously unpublished documents in the Castilian archives, French historians finally learned the correct identity of the brilliant architect who designed Salses. You can even see his flowering signature at the bottom of one of the documents found in bundle No. 140 of the archives. His name was Francisco Ramiro Lopez. Known for his skills in siege attacks, Ramiro Lopez distinguished himself in the battles that recaptured Mirabella and Ronda, among others, from the Moors. The Spanish crown rewarded Ramiro Lopez for his military actions by offering him a number of gifts and awards, including a castle in Andalucia and the right to restore the great palace of the Nasrid rulers, the Alhambra. Ramiro Lopez had previously designed other forts in southern Spain and southern Italy, but Salses was to be his crowning achievement.

Features of the Fort

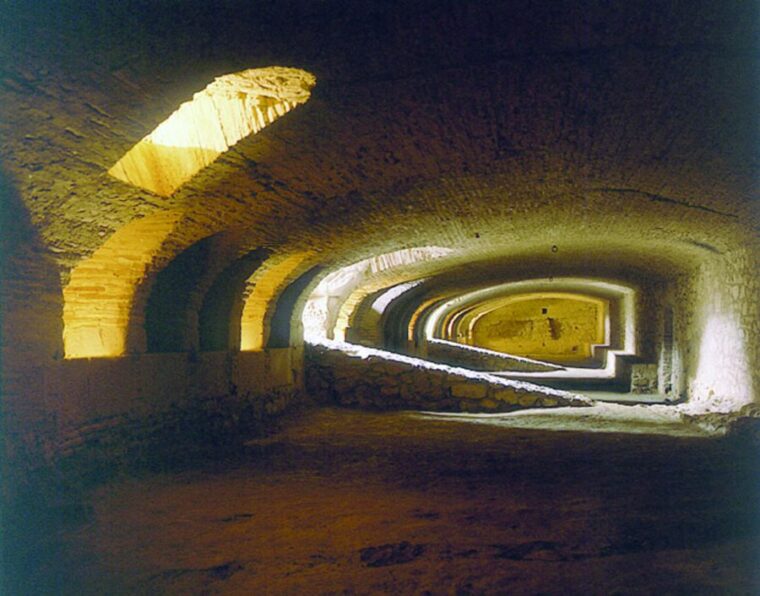

The most striking feature of the military masterwork is the immensely thick, 33-feet-wide escarpment walls that lie deeply embedded in the ground beyond a moat and a sloping glacis beyond. Half the walls’ heights are buried in the ground, presenting a colossal and imposing armored profile to the world. Other features, not so evident, are of equal interest. “Outside, you cannot imagine what’s inside,” notes tour guide Michele Pillierz Tardieu as she guides visitors through long, labyrinthine passageways and confusing corridors that lead to hidden vaults and unexpected galleries. She is not the first to make such an observation. One enemy commander, Sebastien de Pontault de Beaulieu, noted that “there is more room under ground in this castle than above, for it is casemated and countermined all over.”

Above ground, the fort rises between three and seven floors. The overall effect of the vast masonry, as one contemporary observer commented, is “to make Salses not one fortress but several.” Equally exceptional for a fort of its time and place is the technical sophistication of its hydraulic and water systems, used for both military and domestic purposes. The four handsome, extremely tall mudejar—brick artillery towers—functioned as ingenious fire protection and ventilating systems. Each tower contained a well, and the water for each, which came from an underground source, cooled cannons by spraying them with water and removed toxic fumes by absorbing the smoke. “The Spanish learned about hydraulic and water distribution systems via the Muslims,” says Pheline.

Throughout the fort, water was used most cleverly. Sluice gates distributed water to washbasins, to latrines, to the stables for horses, and even to the governor’s private chamber, where he could enjoy a comfortable bath in his own tub, which visitors can still see today. The fort contains not one but two moats, each of which could be flooded with little difficulty. “They knew to flood the canals to choke the French forces so they had to surrender,” Pheline adds. This happened during one of the last sieges of Salses, before the Spanish capitulated to the French in the mid-17th century.

Past and Present

Today, Salses displays an intriguing mix of archaic and modern military elements. The modern ideas reflected important and far-reaching changes in military technology that were becoming ascendant as the fort was being built. Particularly significant was the increasingly sophisticated artillery. Cannons were becoming smaller, lighter, more mobile, and more precise. The addition of trunnions allowed for more accurate aim, while the replacement of stone with cast-iron balls added greater range and force.

Spain learned firsthand the effectiveness of such newly evolving artillery when the French attacked the fortress, not yet completed, in 1503. Although equipped with 17 pieces of heavy artillery, 39 pieces of light artillery, and hundreds of shields, pikes, lances, hackbuts (early handguns), and other weapons, the fort’s 1,350 infantry and cavalry were no match for the French, who fired 1,500 cast-iron cannonballs as they brought down the counterscarp and destroyed much of the fort’s northern outer works.

The Spanish were saved from defeat by the timely arrival of King Ferdinand with a 20,000-man army, but a valuable lesson was learned. “The whole artillery system was changed,” says Pheline. “The walls and towers were thickened, the posterns were transformed. With all the changes, Salses became a much more efficient fort and one of the most powerful ever built.”

The transformed and strengthened fort had a definite dissuasive effect—it was not attacked again for over 100 years. When Salses did fall to the French, it was as much a result of internal Spanish discord and dissent as to the military resources and abilities of the French. Its loss provides a cautionary tale of the price of empire building. The 16th century saw Spanish imperialism run amok. In spite of the enormous riches flowing in from the New World—a spectacular 500 million gold ducats were imported from the Americas between 1500 and 1600—Spain became exhausted economically and physically. In 1557, the crown declared bankruptcy. “God wants us to make peace,” explained the Conde Duque de Olivares, Spain’s chief minister, “for He is depriving us all the means for waging war.”

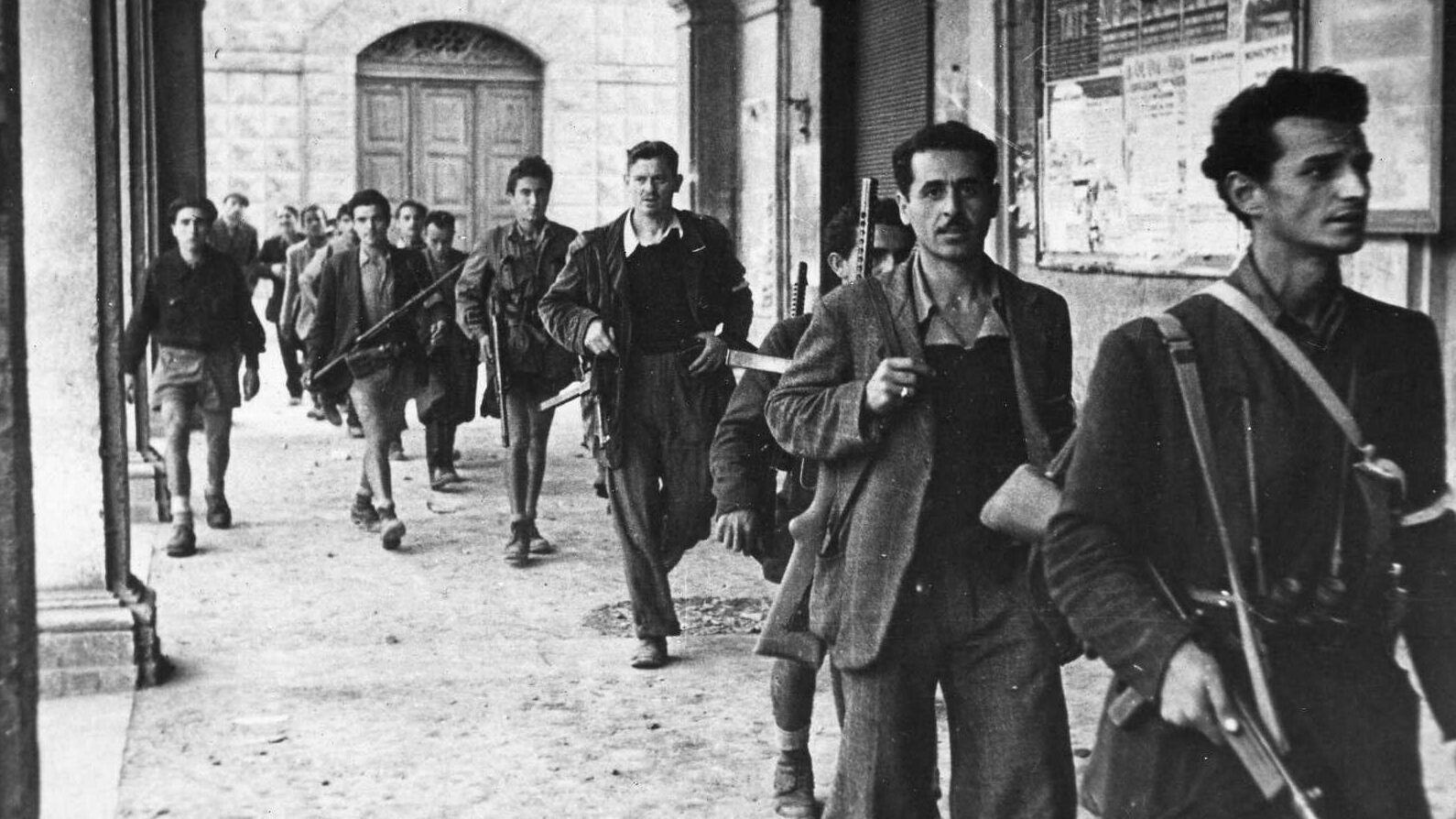

It was Olivares, in effect, who wrote the last Spanish chapter of the Salses fortress. Relentlessly demanding more money, supplies, and troops from independently minded Catalonia to counter the French, who had entered the region and captured Salses in 1639, Olivares encountered a defiant and rebellious local response—riots, revolts, and regular clashes between peasants and soldiers. In effect, a civil war raged between the Spanish crown and the Catalonians. The renowned tercio, the Spanish tactical formation inspired by the Roman legions and Swiss infantry, was deployed against the local populace. During the Catalonian revolt, Salses passed back and forth between Spain and France. By 1643, Olivares had been forced to retire in disgrace, and Salses was no longer a Spanish possession.

The formal end came in the autumn of 1659, when the ministers of a resurgent France and a diminished Spain met on a neutral spit of land in the middle of the Bidassoa River at Bayonne, France. The meeting resulted in the Treaty of the Pyrenees. In language that was at once pompous, questionable, and inexact, the treaty declared that “the Pyrenees Mountains which anciently divided the Gauls from the Spains, shall henceforth be the division of the two said kingdoms.” The practical effect of the treaty was to cede from Spain to France significant territory, including almost all of Catalonia north of the Pyrenees. Salses became French.

Today, the azure waters of the Mediterranean have receded far from the old shoreline. The formal boundary line separating the two countries for the past three centuries is a moot scribble in a quasi-unified continent. But the tumultuous past is not forgotten in this small corner of the world. Yards away from the fortress, on a plain brick wall, is graffiti in the Catalan language: “Catalonia is neither Spain nor France.”

The fortress is open throughout the year; hours vary according to season. Guided visits in English are available. For more information, visit the official French website at http://salses.monuments-nationaux.fr/en/

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments