By John J. Domagalski

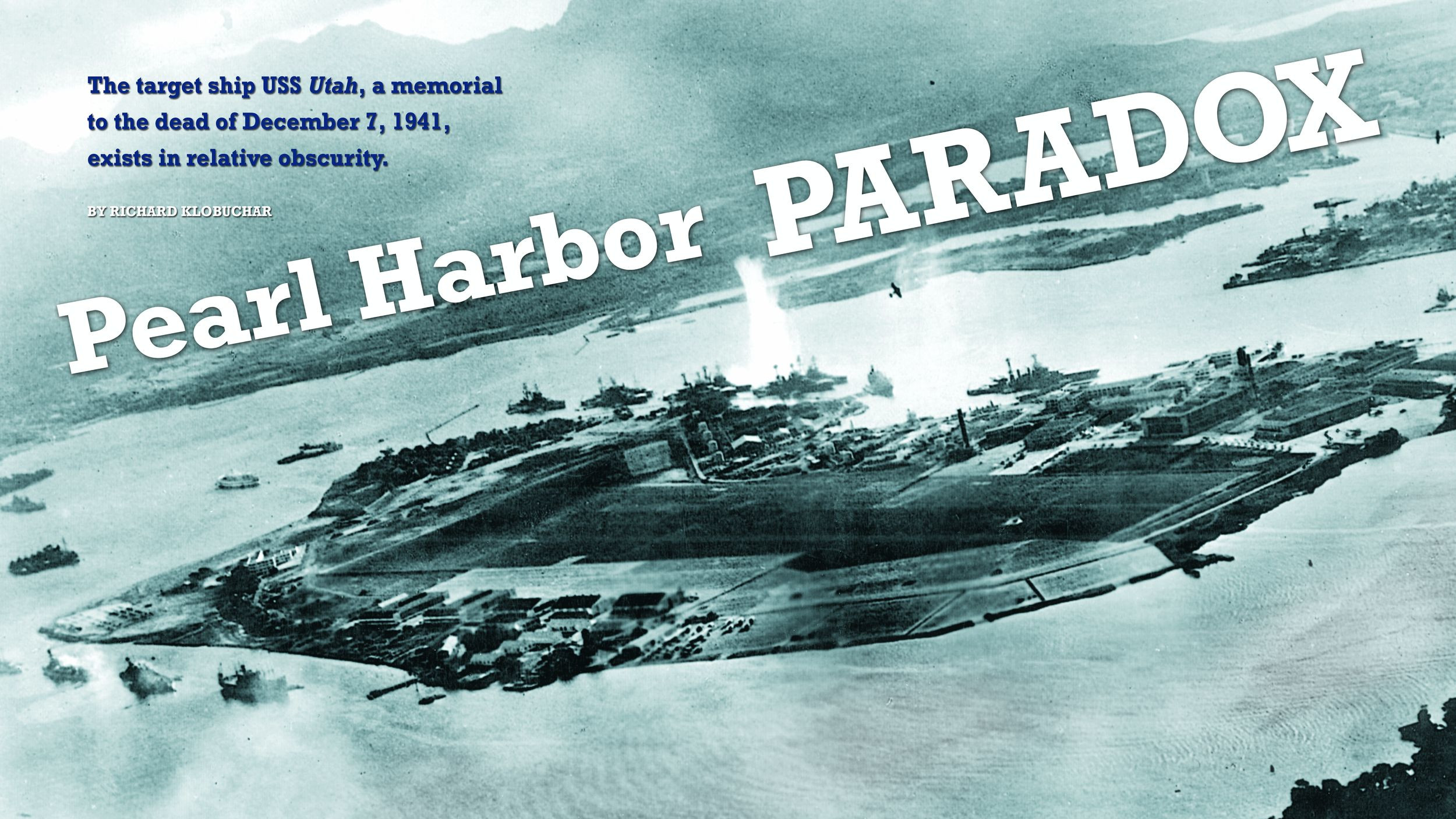

The fading daylight of August 6, 1942, found the American heavy cruisers Astoria and Chicago as part of Task Force 61, under the command of Vice Admiral Jack Fletcher, steaming toward the South Pacific island of Guadalcanal. The force that was to deliver the first American amphibious invasion of the Pacific War—Operation Watchtower—had thus far escaped Japanese detection. The final approach to Guadalcanal lay ahead.

The final hours of the day found the ships of the amphibious force plodding along at 12 knots, bound for the almost 20-mile-wide channel that separated the northwest tip of Guadalcanal from the Russell Islands. As midnight passed, the sky remained overcast, blotting out the moon and keeping the visibility poor. Conditions, however, began to get better during the early morning hours. Visibility, too, began to improve shortly after midnight.

From their forward positions and through the dark of night, the destroyers Bagley and Henley led the task force into the waters off Guadalcanal. At 1:33 am, Henley sighted a dark mass on the horizon. Guadalcanal was now in sight.

From her position right behind the cruiser San Juan, lookouts aboard Chicago quickly sighted the coast. The cruiser was steaming at 12 knots with six of her eight boilers in use. The crew was at Readiness Two. Under the semi-alert arrangement, half the crew was at its battle stations, while the other half rested off duty. The two groups rotated every four hours.

The stroke of midnight brought a change of watch aboard Astoria. Commander William H. Truesdell climbed into position at sky control. The 39-year-old officer had graduated with the Annapolis class of 1925 and had been promoted to commander right after the Battle of Midway, June 1942. As gunnery officer, he was responsible for just about everything related to the ship’s armament.

Located near the forward main battery director, sky control was high up on the superstructure––the control center for the cruiser’s guns. From his vantage point, Truesdell would direct the preinvasion bombardment later in the morning. At this particular time, the area was filled with a crowd of men busily going about their duties. Lookouts manned the outdoor areas, carefully scanning the horizon with their binoculars.

By way of headphones, Truesdell was connected to various key parts of the ship. He quickly was brought up to speed on the latest information. There was no contact with the Japanese. Apparently TF 62 had not been sighted. Outside some stars could now be seen. It was not long before men aboard Astoria also sighted Guadalcanal. The land mass was dark, and it seemed as if the island was sleeping.

At about 3 am, the task force was located just off the northwestern tip of the island and it was time for the two squadrons––“Yoke” and “X-Ray”––to split. The Yoke Squadron turned slightly to the northeast and began to venture around the north side of Savo Island. Chicago maintained her position behind San Juan, then went to general quarters at about 3:30 am. The X-Ray Squadron and Astoria turned to the east and entered the narrow passage between Savo and Guadalcanal. The distance between the islands was only about 71/2 miles. The ships were truly entering the unknown.

Aboard Astoria, Captain Greenman wanted to make sure his ship was ready for action early. “I decided that 2 am would be the right time to go to general quarters,” he recalled, “but I had no instructions at that time or any other time.” Helmets and life jackets were donned as every sailor reported to his battle station. Every lookout had to be extra alert.

It was possible that Japanese patrols were lurking in the vicinity of Savo Island. The water was calm and could be heard slapping against the ships’ hulls, while the waves could be heard breaking against the shore in the distance. A quarter moon had risen in the northeast, silhouetting the islands. The partial moon provided just enough light for good visibility. As fate would have it, no Japanese were encountered. The ships peacefully cruised past Savo Island unmolested.

During the last hours before dawn, the final preinvasion preparations were completed. Aboard the transports heading for Guadalcanal, the men of the 1st Marine Division were up at 4:30 am and ate a heavy breakfast. Many would soon be nervously loitering on deck, lining the rails to get a good look at the distant island. Before long, the Marines, loaded with rifles and packs, would be waiting on deck to board the landing craft.

Aboard the aircraft carriers of Fletcher’s TF 61, sailing in the waters southwest of Guadalcanal, the flight decks were loaded with planes. The pilots aboard the Saratoga had gathered one last time the night before for a final review of the maps. They had been studying their impending missions nightly during the voyage north. Blue exhaust streaked from engines of planes that were warming up on the flight deck in the predawn hours. At about 5:35 am, the first plane, a Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter, rose from the flight deck of Enterprise. A total of 93 planes were soon airborne and on the way to the Guadalcanal area.

Final Approach

The early morning light revealed Guadalcanal and Tulagi for the first time in full color. The weather was generally clear except for a few scattered clouds. Some light mist or fog was hovering in the area but seemed to be burning off.

As Chicago passed Guadalcanal bound for Tulagi, Fred Tuccitto was among the sailors who wondered what the next day would hold. “[The Japanese] knew what it was like to be in a war. We didn’t,” he recalled. “We had no inkling of what we were getting into. I don’t think anybody knew.”

For the men who were on deck, it was a chance to see the islands that they had heard so much about. Ken Maysenhalder was at his battle station, a 5-inch gun mount on Chicago’s starboard side. “Approaching the island of Guadalcanal, I could smell the aroma of tropical plants as the wind blew the smell out to sea. All was quiet as we approached the island,” Maysenhalder recalled the calmness. “It was very eerie.”

Charles Germann was topside on Enterprise during the approach. “I was on the flight deck for some reason,” he remembered. At first he had trouble seeing the islands off in the distance, but his view improved, and he recalled, “I could see everything.”

Fred Tuccitto recalled the first time that he saw the island. “It was sort of covered with a lot of clouds,” he said. “It was sort of mysterious. As we approached the island, we could see land on the horizon. And then you don’t see it. And then you see it. Finally we got pretty close to the island. You could smell it. It smells different than being out in the ocean.”

After arriving off Tulagi as part of the Yoke squadron, Chicago stayed with the transports as she did not have a specific gunfire assignment.

Gene Alair was at his battle station on the forward 1.1-inch gun mounts as Astoria nudged closer to Guadalcanal. “You could smell it. We knew we were getting near land,” recalled Alair. “We knew what we were doing, but it was new to us. We had never gone into an amphibious operation.”

Also topside was Henry Juarez. He was manning the 1.1-inch guns near the stern of the ship. “We knew we were going into something,” he said. “Early in dawn in the morning, we could see the islands. It was dead quiet.”

Like many others, pilot Richard Tunnell simply remembered the approach to Guadalcanal as being quiet. “It was spooky,” he said. “It was an eerie sensation.”

Off the coast of Guadalcanal, Astoria was following the cruisers Quincy and Vincennes toward the fire-support position. The three heavy cruisers were joined by four destroyers. There appeared to be no activity on land as the seven ships quietly approached the island.

Intelligence made available to Astoria as part of the operation plan suggested that supplies, motor vehicles, and antiaircraft guns were likely in her assigned bombardment area. In the days leading up to the invasion, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortess bombers had reported the existence of 12 antiaircraft guns at various locations on the island.

At exactly 6:13 am, the silence of the morning was shattered by the tremendous blast of Quincy’s 8-inch guns. Directed to the west of Lunga Point, her shots soon started a large fire. Vincennes then spoke with an 8-inch salvo of her own. Finally, it was Astoria’s turn. Her three turrets trained out to the starboard side, and she opened fire with a full nine-gun main battery salvo directed at the area east of the Lunga River. A flash of light coming from the 8-inch guns was quickly followed by thin streaks of red heading in the direction of land. A flash ashore indicated the approximate point of the impact.

When Astoria opened fire, Chaplain Matthew Bouterse was below deck at his battle station, but his location did not stop him from wanting to see the action. “I managed to snatch a few quick glimpses through a hatch that we had loosened in the huge watertight door that led topside from the chief’s quarters,” he later recalled. He soon paid the price when the concussion of an 8-inch salvo sent the hatch crashing down on his head. He later returned to the viewing point wearing his steel helmet for protection. With the firing of the 8-inch guns, he saw red streaks reaching out to the beach area. “I can still remember the way the concussion of those blasts felt in my gut. And this was the sending end!”

As Guadalcanal shook from the rumble of explosions, coconut trees became uprooted and crashed to the ground as debris flew through the air. By many accounts it was a spectacular show of force. Shortly after the bombardment began, a flare or series of small rockets shot up from the island in the direction of Tulagi. Perhaps it was some type of belated warning.

In what seemed like only a matter of a few minutes since the bombardment started, the carrier planes suddenly appeared overhead, roaring past Astoria to begin the attack from the air. Fighter planes swooped down near Tulagi, shooting up the Japanese seaplanes that bobbed on the water; all seven of the large, four-engine flying boats, as well as the nine floatplane fighters, were destroyed on the water. No Japanese planes made it airborne.

From his gun mount on Chicago, Ken Maysenhalder saw the planes coming in for the attack. “After only a few minutes,” he recalled, “all hell erupted. Overhead our carrier planes approached and dropped bombs. When these bombs hit the target, you could feel the explosion and the impact that they made.” Additional fighters and dive bombers pounded targets on Tanambogo, Florida, and Guadalcanal.

The naval bombardment continued. Each time Astoria fired her 8-inch guns, the entire ship shook from the concussion. There was a slight pause between salvos, just enough time for minor adjustments to be made to the bearings. Astoria poured salvo after salvo onto Guadalcanal with no return fire coming from the island.

Action was suddenly taking place at sea off Astoria’s port bow. The destroyers Dewey and Selfridge were firing at some type of small craft. An observer aboard Astoria believed that the target was a Japanese patrol boat. However, it was actually a small schooner loaded with gasoline that had initially been set aflame by the carrier planes. The destroyers finished off the boat, which burned furiously before going under. It was now time for the Marines to get into the action.

Invasion

Exactly eight months to the day since the attack on Pearl Harbor, the first full-scale American amphibious operation since the Spanish-American War was about to begin. As the sea and air bombardment drew to a close, the transports moved toward the assigned beach. The decks of the transports were crowded with Marines, each carrying a rifle and loaded down with various packs. Davits swung outward and slowly lowered landing craft into the water, each of which carried a small American flag perched on the stern. Marines then descended rope ladders into the bobbing craft below.

Off Guadalcanal, the transports slowly glided to a stop at a debarkation point that was 41/2 miles directly north of the beach area. The final step before the Marines could go ashore was a thorough blasting of the beach. As the first wave of fully loaded landing craft began to move away from the transports, the bombardment force moved into position.

Seven ships were assigned to fire away at the landing zone. Astoria and four destroyers covered the actual landing beach plus an additional 800 yards on each side. The ships had been instructed to fire from the water’s edge to a depth of 200 yards inland and to avoid hitting wharves, jetties, and bridges that did not appear to be threats.

The bombardment commenced at 9:03 am with the thundering roar of gunfire. Gun crews aboard Astoria worked at a feverish pace to keep up the bombardment. Five-inch guns cracked out single shells as the main batteries shot sheets of flame. As the shellfire continued, the landing boats sped toward the beach, maneuvering in a 1,600-yard-wide channel that was marked by a destroyer on each side. Directly in front of the small boats, the beach area was a mass of explosions. As the landing craft came to within 1,300 yards of the beach, the guns fell silent. The bombardment was over, having lasted only about six minutes. In the short time, Astoria had expended 45 rounds of 8-inch and 200 rounds of 5-inch shells.

From his vantage point in the forward antiaircraft director, John Powell had a bird’s eye view of the bombardment. “Before the troops went ashore, we bombarded all the area where they were going to land; knocked down a lot of coconut trees,” he said. “It didn’t hurt anything, just shook up a couple of natives over there.”

In the aftermath of the bombardment, a thick haze of dirty smoke floated in the air over the beach. Just four minutes after the firing stopped, the first troops landed without opposition and the Marines quickly advanced inland about 600 yards to establish a beachhead. No Japanese were encountered. Word quickly reached Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commanding the amphibious force of Task Group 61.2, that things ashore were going better than expected.

Scouting Mission

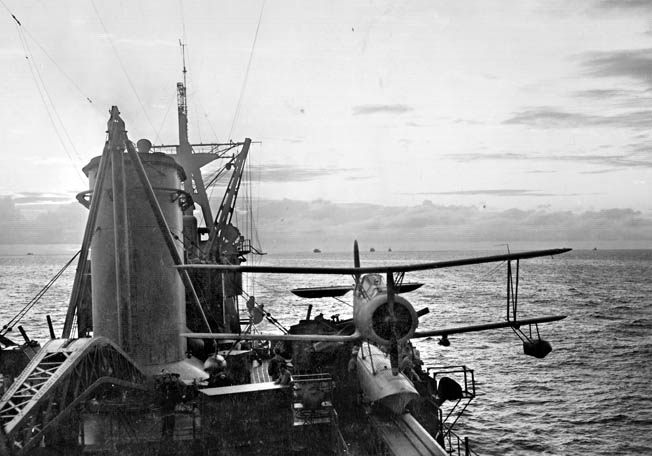

Astoria’s scout planes were called on to participate at the very start of the landing operation. As the senior aviator aboard Astoria, Lieutenant Allan Edmands flew the first flight off the cruiser. Most of the initial missions were related to fire support, with the planes acting as spotters for the ship’s gunfire. However, with no opposition reported ashore, the air patrols later shifted to antisubmarine flights.

Richard Tunnell was one of the pilots assigned to fly a morning mission over Guadalcanal. His specific mission was to fly over Red Beach, repeatedly dropping smoke flares at each end, and then acting as a forward spotter. His rear-seat passenger for the flight was Marine Major Campbell. Just prior to departure, Tunnell reported to Captain Greenman for final instructions. The captain warned him of Japanese float fighter planes reported to be at Tulagi. The thought crossed the pilot’s mind that Greenman believed that he was not coming back. “When he said goodbye,” recalled Tunnell, “I think he meant it.”

Just after launching, Tunnell spotted two planes diving down close to his position. He felt a bit unnerved but was relieved when they turned out to be American fighters. A short time later he caught a glimpse of tracer bullets passing below the plane on the right side. Believing his plane to be under fire, Tunnell immediately began evasive maneuvers. He yelled back to check on Major Campbell. “I was just test-firing the machine gun,” the Marine replied. The mission continued, although with a somewhat irritated pilot.

At the appointed time, Tunnell guided his plane over the beach. The bombardment of the landing zone had just been completed. Campbell dropped the smoke flares, replacing earlier ones that were on the verge of burning out. Emerging from the beach area, Tunnell banked his plane and headed over the island, swooping in low for a close look at the Japanese airfield that was under construction. Flying over a nearby camp, he noticed smoke gently wafting up from some cooking grills; there was no sign of the Japanese. Tunnell soon noticed some type of warehouse that the Japanese had constructed under a cluster of coconut trees and decided to attack it.

Climbing back to 2,000 feet, the plane dived down and unleashed two small, 100-pound bombs on the structure. After pulling up, Tunnell yelled back to Major Campbell to see if he had observed any hits. There was no reply. Turning around, he soon noticed that the major was out cold. The observer had not properly secured the rear machine gun after his earlier surprise test firing. During the dive, the gun swung around, striking the Marine in the head and knocking him out.

Additional searches of the immediate area yielded no sign of the Japanese. “We could see the Marines getting ashore,” Tunnell said. “Everything was quiet.” With the mission completed, the pilot and passenger headed back to Astoria after having been in the air for almost five hours.

By midmorning, the Marines on shore began to advance west, moving along the coast toward the Lunga River. Astoria was assigned to follow the westward progress of the troops along the beach, then stand by to provide gunfire support as needed. However, since no Japanese opposition was encountered the fire support was not necessary.

While Astoria was fulfilling her duties as part of the bombardment group, Chicago continued to operate with the screening group. The ship cruised at various speeds near the transport area off Tulagi. The operation plan called for Chicago to stay under way just outside of the 100-fathom curve in close proximity to the transports. The screening force was now operating without the four cruisers and six destroyers that had departed to shell the beaches.

Just after 8 am, Chicago launched two seaplanes for antisubmarine patrol; 20 minutes later an additional plane was launched for the same duty. The original two planes were recovered after spending about an hour in the air. The alternating process of launching and recovering planes continued throughout the late morning hours. However, Chicago’s role of hosting the fighter director officer would soon be taking center stage.

Complete Surprise

Japanese naval leaders believed that the Solomon Islands would be the scene of an American counterattack. However, such a move was not expected until sometime late in 1943. The first indication of trouble in the Guadalcanal area on the morning of August 7 came to the major Japanese naval base at Rabaul in a plain-language emergency radio message. The commanding officer of the Tulagi communication base reported, “Enemy surface force of 20 ships has entered Tulagi. While making landing preparations, the enemy is bombarding the shore.”

A later message reported one battleship, three cruisers, 15 destroyers, and various transports in the waters offshore. The final message was received just short of two hours after the initial warning: “Enemy troop strength is overwhelming. We will defend to the last man. We pray for the continuance of military fortune.” A short time after the last message was sent, gunfire from San Juan knocked out the radio station, silencing the Tulagi garrison forever.

The Japanese commanders at Rabaul wasted no time preparing a response to the American landings. The initial task fell to Rear Admiral Sadayoshi Yamada, commander of the 25th Air Flotilla. On the airfields around Rabaul, he had at his disposal an assortment of bombers and fighters. As it turned out, the Japanese already had an attack force ready. Only a few days earlier the Japanese discovered the existence of a small Allied airfield at Rabi on the far eastern end of New Guinea. In the hours before dawn, ground crews had prepared 27 bombers and nine fighters for an attack.

The stunning news from Tulagi suddenly changed the mission. Admiral Yamada quickly issued new orders for the planes to instead attack Tulagi. Additionally, he directed nine dive bombers to attack. The transports were to be the main target unless the American carriers, assumed to be part of the operation, could be located.

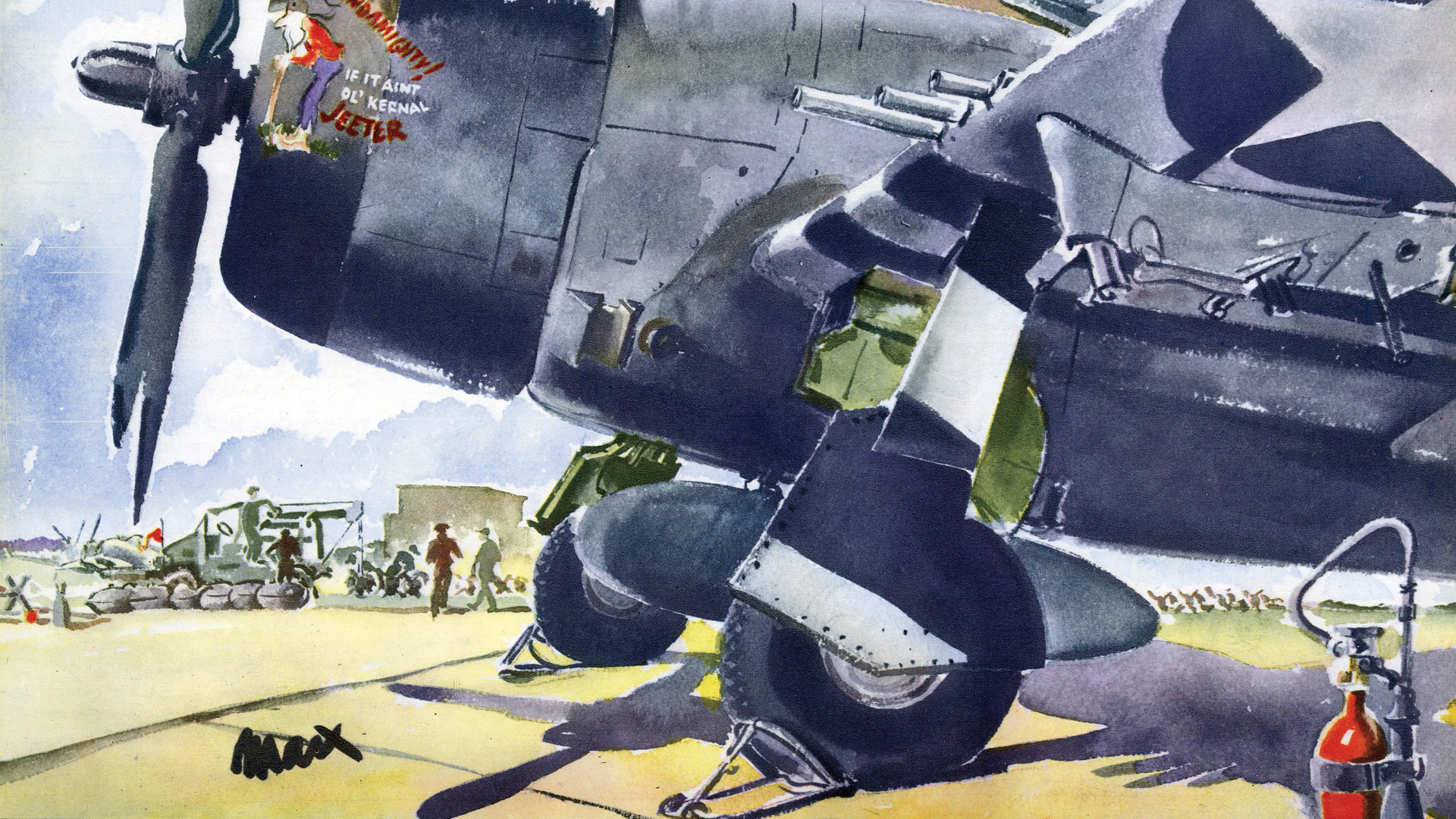

The Japanese bombers were no strangers to American sailors. The Mitsubishi G4M1 entered service in April 1941. Officially named the “Navy Type 1 Attack Bomber,” the plane was known to the Allies as the Betty. The twin-engine, land-based bomber had a long, thin cigar-like fuselage. The Betty was fast and had a long range, but it lacked armor protection for the crew of seven. An internal bomb bay could carry four small bombs, two larger bombs, or could be modified to carry a torpedo.

Chicago had survived an attack in the Coral Sea by Japanese twin-engine bombers of a similar type nearly three months earlier. Bill Grady remembered how Captain Bode’s seamanship helped the cruiser survive the attack. “He wasn’t afraid of nothing,” Grady said. “In the Battle of Coral Sea he was at the helm and he saved us. If one [torpedo] was at starboard, he would swing the helm to port. It would lean to starboard and it would bring the keel up out of the water and the torpedo would go under us.”

Aerial Encounter

The 27 Bettys took to the air at about 10 am. Since there was no time to switch to torpedoes, the planes contained the same payload of bombs intended for the Rabi mission. The escort was increased to 18 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, as American carrier planes were expected to be in the area. Scout planes scurried out just ahead of the bombers in hopes of locating the carriers. After departing Rabaul, the planes traveled southeast over Bougainville.

About an hour after the main attack group departed, a second group of Japanese planes took flight. Nine Aichi D3A Val dive bombers comprised the second wave of the air attack. Flying without the benefit of a fighter escort, the single-engine planes did not have the range to make the round trip so, after attacking the American ships, the pilots were instructed to ditch their planes off the southern coast of Bougainville where a flying boat and seaplane tender would be waiting to pick them up.

From a perch atop a hill in southern Bougainville, Australian coastwatcher Paul Mason took note of the first group of passing planes. As the planes roared past his jungle hideout, he quickly counted the bombers and transmitted a radio message using an emergency frequency. The message was picked up by Pearl Harbor and quickly relayed to the invasion fleet.

With the news that enemy planes were on the way, the task force sprang into action. A simple message, hoisted from the flagship read, “Repel air attack.” The transports ceased unloading operations and made ready to get under way. In the event of an air attack, the ships of the screening force were to form a tight ring around the transports.

At 10:40 am, Chicago received the warning that enemy planes were approaching; at the time she was patrolling with the cruiser HMAS Australia and destroyers Henley and Helm near the Yoke transports. Lieutenant Bruning, the guest fighter director officer from Saratoga who was stationed aboard the cruiser, would have his work cut out for him over the next day and a half. Bruning and his small staff controlled the fighters that were providing combat air patrol over the transport area.

The Japanese attack force winged its way south, reaching the approximate halfway point over the island of Vella Lavella in the Central Solomons. The jagged mountains of Guadalcanal came into view when the planes reached the Russell Islands; the target was only about 50 miles ahead. Scattered clouds hung at about 13,000 feet with clear sky above and below.

Approaching the target area, Japanese pilots were astonished at what they saw. The wakes of the ships below appeared as hundreds of white lines in the waters off the northern coast of Guadalcanal, and the warships, transports, and landing craft were simply too numerous to count.

The 27 Japanese bombers flew in three tight formations of nine planes each and approached the waters between Guadalcanal and Tulagi from the northwest, passing over Savo Island.

At 1:14 pm, the enemy planes appeared on Chicago’s CXAM radar set at a distance of 43 miles. Just then, 12 Wildcat fighters from Saratoga tore into the attacking Japanese formation. Some of the fighters were able to make a clean pass at the bombers, but others were jumped by the escorting Zeros.

Less than 10 minutes after the radar sighting, lookouts aboard Chicago visually sighted 25 bombers and three escorting fighters. Two minutes later, the lookouts reported that one bomber dropped out of formation and was falling toward the water in flames as an air battle shaped up. It looked as if the enemy planes were headed toward the X-Ray transports.

The bombers were outside the effective range of the cruisers antiaircraft guns but within range of the ships that were off the beach. Dots of antiaircraft fire soon began to appear in the sky, but the enemy planes came on.

John Powell was on duty in his director when he received word that enemy planes were on the way. He remembers Astoria being about five miles from the transports. “I heard it on the radio,” he recalled. “We were off of a big plantation area on the west end of the island between Lunga Point and Cape Esperance.” As the bombers moved closer to Astoria, Powell’s director started tracking the incoming planes. “We tracked them just to find out how fast and how far they were going. They were making 165 knots.”

The young fire controlman remembered the high altitude and tight formation of the approaching planes. Then he saw the bombs fall. “We could see the bombs coming down. Everybody dropped their bombs at once,” he said. Powell felt that the planes were too high for effective antiaircraft fire.

The bombers dropped their deadly payloads in unison from an altitude of almost 12,000 feet. The mass of bombs curved slightly during the long drop to the sea before exploding harmlessly in the water between some of the cruisers and the X-Ray transports. The formation of bombers then banked to the left for the journey back to Rabaul.

As a Marine aviator, Roy Spurlock was not accustomed to seeing air attacks from a ship. “I shall never forget the silver of those Betty bombers directly overhead in formation,” he recalled from his position aboard Astoria, “silhouetted against the blue sky over Guadalcanal. This attack was quickly over and the invasion continued.”

From his battle station on Chicago, Art King gazed into the distance and saw a group of American dive bombers tangling with a Japanese fighter. “I saw three of our dive-bombers flying low in formation,” he said. “All of a sudden, I could see this little plane way behind them, but catching up in a hurry and, of course, it was a Zero. As it got into range, the three SBDs started firing at it, and the little old fighter did a 90-degree turn going straight up and disappeared. So the three dive bombers went ahead to their target and did what they were supposed to do.” It was just one of the many battles that took place on that particular day in the sky above Task Force 62.

One of the American planes shot down was piloted by Ensign Joseph Daly of Saratoga. His Wildcat was caught from behind by Zeros as he was readying to make another pass at the bombers. A 20mm shell exploded somewhere under his cockpit, and suddenly everything around the young pilot, including his clothing, was on fire. Managing to open the canopy and unfasten his belt, Daly jumped out of his stricken plane, barely clearing the tail. A Japanese Zero streaked by as Daly began to freefall toward the water almost 13,000 feet below. Pulling the ripcord at about 6,000 feet, he landed in the water some two miles from Guadalcanal. He could see ships on the horizon and began to swim in that direction.

With the attacking planes gone from the area, Chicago resumed her position in the screening force near the Yoke transports. Just after 2 pm, the cruiser catapulted off two seaplanes for antisubmarine patrol. The task force had received a message from Pearl Harbor earlier in the day warning that enemy submarines were en route to the area, so the planes flew low to scour the area for any sign of the underwater craft.

Meanwhile, Ensign Daly was not making much headway swimming toward the distant ships. Several destroyers had passed near his position but had not noticed the downed aviator. After being in the water for about two hours, he heard the sound of a plane coming up from behind. It was one of Chicago’s seaplanes. The pilot, Ensign John Baker, noticed the downed flier waving and splashing in the water. He circled his seaplane around and came in for a landing. Baker drew his pistol as he pulled up, not sure if the darkened face in the water was American or Japanese. Daly believed that there was a good chance that he was going to be shot. However, the Chicago pilot quickly saw that the downed aviator was an American. With his left leg wounded, Daly struggled to get aboard the plane. He was soon airborne riding on the lap of the back-seat radioman. Baker initially wanted to drop off his wounded passenger at the first heavy cruiser he came upon, Vincennes. However, he decided to continue on to Chicago.

The second wave of Japanese aircraft arrived in the Guadalcanal area just before 3 pm. The nine Val dive bombers had flown down the north side of the Solomon chain, keeping out of view of the coastwatchers as well as off the radar sets of American ships. Entering the sound over Florida Island, the pilot’s vision was obscured by cloud cover, blocking out the ships of the Yoke squadron below. The Japanese planes continued on toward Guadalcanal.

Appearing unannounced near the ships of the X-Ray squadron, the attackers were quickly jumped by as many as 15 American fighters. Five of the bombers were shot down, but not before one successfully planted a bomb on Mugford. The destroyer was the first American ship to be damaged in the Guadalcanal campaign. The four remaining Vals splashed near Shortland Island, just south of Bougainville. The surviving Japanese crewmen claimed to have damaged two light cruisers.

At 4:35 pm, Chicago recovered both of her seaplanes. Joseph Daly was hoisted aboard and immediately carried down to sickbay for treatment by the ship’s doctor. The pilot was soon diagnosed as having second-degree burns and a gunshot wound to the left leg. His prognosis was recorded as favorable.

Progress on Land

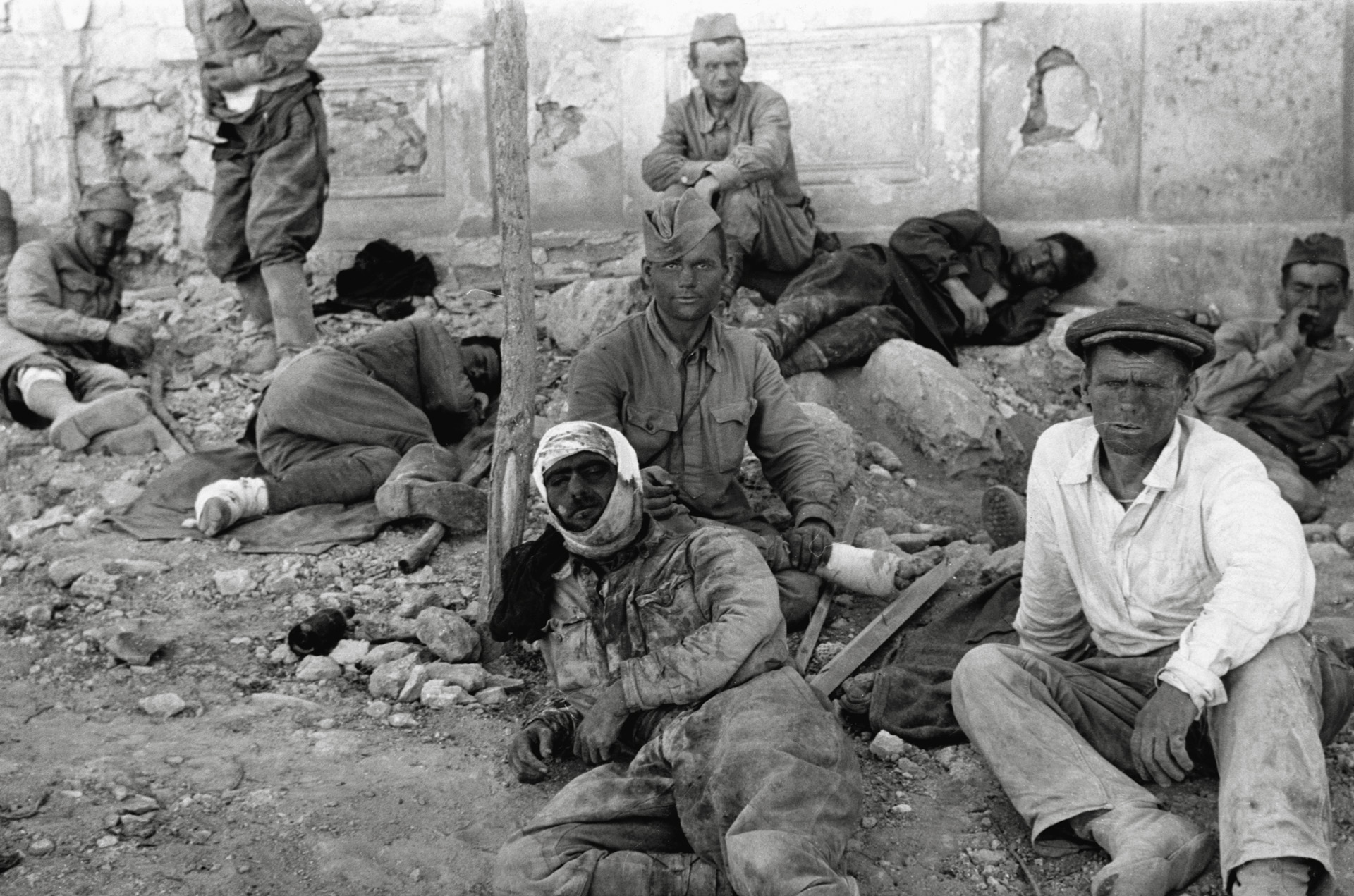

While the ships were fending off the air attacks, operations on land continued throughout the day and into the early evening hours, and the Marines on Guadalcanal were advancing steadily inland from the beachhead without much resistance. The 2,500 laborers and 150 Japanese troops on the island had disappeared into the hills soon after the opening bombardment had begun.

The initial landing on nearby Tulagi had also been relatively uneventful. However, heavy fighting erupted in the afternoon as the Marines approached the southeastern end of the island. The small Japanese garrison was well entrenched there and was prepared to fight to the death. Reports of heavy American casualties soon reached Admiral Turner aboard his flagship, the attack transport McCawley. By the end of the day, the Japanese were still clinging to positions on the southeastern tip of Tulagi.

Uncertain Future

The night of August 7-8 was uneventful for the sailors aboard Chicago and Astoria. Both cruisers patrolled the waters around Guadalcanal and Tulagi as part of the screening force. As the night progressed, Chicago went off general quarters and set condition two. It was time for some of the weary sailors to get much needed rest. As the night progressed, the junior officer of the watch made two inspections of the lookout stations to make sure that the lookouts were alert and had received proper instructions.

On Astoria’s first night off Guadalcanal, John Powell stood watch at his director. He alternated duties with Chief Fire Controlman Henry Henryson. “He was an old China hand, as nervous as anything,” recalled Powell of Henryson. Each worked a six-hour shift, two hours longer than the normal condition two shifts.

Some of the men aboard Astoria had received piecemeal reports of the day’s operations ashore: no opposition on Guadalcanal and fighting on Tulagi.

Looking at Guadalcanal through a set of binoculars, an observer aboard the cruiser saw men, trucks, and tanks on the beach, with some tents nearby. It had been a long and exhausting day, and no one knew what tomorrow would hold. There would be plenty of combat ahead.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments