By David Alan Johnson

Sixty-four-year-old Robert Stubbs slowly walked across the playing field of the Staveley Road School in the West London suburb of Chiswick. As caretaker of the school, Stubbs had already put in a full day at his job. But he still had a few things to do even though it was well past 6 o’clock in the evening.

Most residents of Staveley Road had already arrived home from work as the clock approached 7 pm on Friday, September 8, 1944. Because of the misty drizzle that had been falling all afternoon, and threatened to turn into a steady rain, nearly everyone stayed indoors behind their blackout curtains. Only one other person was out in the light rain. Stubbs caught sight of an Army private walking briskly past the nearby houses, on his way to visit his girlfriend.

At 6:44, Stubbs was picked up and hurled 20 feet across the playing field by an overwhelming blast. There had been no warning at all. He had been making his way across the school grounds; the next thing he knew, he was sprawled on the grass.

When he got to his feet, he was astonished to find the houses on both sides of the street mostly demolished. Most had no roofs. All that was left of some houses was a single freestanding wall rising above a pile of rubble.

11 Houses Destroyed, 27 More Seriously Damaged

Stubbs staggered over to the nearest dwelling, where he saw a gray-haired woman crawling out of the ruins. He tried to do something to help, but by the time the ambulance and rescue squads arrived the 65-year-old woman had died.

Robert Stubbs had been lucky. The explosion killed two people, including Private Frank Browning, who had been walking to his girlfriend’s house. Twenty others had been injured, trapped inside their smashed homes. Eleven houses were totally destroyed. Another 27 were seriously damaged, and had to be evacuated.

People from nearby streets began filtering over to Staveley Road to see what had caused the sudden and very loud noise, which one witness described as sounding “just like a gas main going off.” They found a crater, about 30 feet wide and 10 feet deep, in the middle of the road. The closest houses had been blasted into piles of debris. Ambulance attendants methodically bandaged the wounds of those who had been pulled out of the wreckage by the rescue squad.

Two RAF officers soon arrived and began prowling about the inside of the crater. They picked up bits of metal and, after a quick inspection, dropped them into their briefcases. The two were eventually joined by American officers and London Civil Defence officials.

A reporter cornered one of the Civil Defence men and asked if the explosion could have been caused by some new kind of robot bomb. Any reply would have been strictly off the record—censors would not allow any mention of the incident in the press, the reporter knew—but the CD official refused to give any information. “We can’t tell you what it was,” he said. “It might have been a gas-main explosion.” The reporter didn’t believe the story. The Civil Defence man didn’t expect him to.

In the north London suburb of West Hampstead, Mrs. Gladys Cox also heard the explosion. She had been listening to the radio, sitting with her cat in her lap. The sudden boom shook the chair and startled the cat to its feet. A few seconds later, her husband Ralph came running in. “Had you heard that one?” he shouted. Cox described the noise as “a single, very loud crack … something like that of a gun.” “I just wonder if it is some munitions’ work explosion,” Mrs. Cox thought to herself, “or the heralded V-2!”

All over London people heard the blast. Sixteen seconds after the Staveley Road explosion, another unexplained boom rocked the district of Epping in northwest London, causing no casualties. Londoners could only guess at what it was. U.S. intelligence worker Richard Baker was told that a bomber had crashed. Hilda Neal of South Kensington thought that it must have been “an extraordinary thunderclap, because there was no reverberation.” After thinking about it for a while, Miss Neal added, “Some new horror, I suppose.”

The Beginning of the German V-2 Missile Attack

Duncan Sandys, who had been appointed to investigate the German missile program a year earlier, was in Shell-Mex house, next to the Savoy Hotel on the Thames Embankment. Immediately after the jolt, he heard a second sound, which was ignored by most Londoners—a heavy object rushing through the air, which later would be compared with a train passing overhead. This was the rumbling of the missile through the earth’s atmosphere, on its way to impacting on its target. Traveling several times faster than sound, it had outrun its own noise. Sandys knew all too well what had caused the explosion—the V-2: the German guided-missile attack had finally begun.

Germany had initiated its rocket program even before Hitler came to power, as far back as 1929. The Army’s Weapons Department had taken a liking to rockets because they were one method of getting around the hated Treaty of Versailles. Signed by the Allied powers and Germany at the end of World War I, the treaty limited Germany to a very small army, reduced the size of the German navy, and prohibited submarines. It made no mention of rockets, however.

For director of the new rocket program, the Army appointed 35-year-old Reichswehr Captain Walter Dornberger. After serving in the Army during the war, Dornberger was allowed to stay in the Reichswehr, which was the name for the German Army at that time and which was limited to 100,000 men by the Versailles Treaty. Dornberger was an artillery officer and was also an engineer. His new job as head of the still nonexistent missile department appealed to him. By 1932, Captain Dornberger was hard at work on a rocket called, simply, Aggregat 1, (a designation meaning “prototype”) or A-1.

While at work on A-1, Dornberger hired another young man as an assistant, a young rocket enthusiast named Wernher von Braun. Von Braun had been interested in rocketry and space exploration since childhood and had belonged to an amateur rocket club in Berlin. But in the 1930s, depression and unemployment plagued Germany. Von Braun’s experiments stopped because of lack of money.

When Captain Dornberger asked von Braun to join him at the Army Weapons Department at Kummersdorf, south of Berlin, the 22-year-old scientist jumped at the chance. At Kummersdorf, his rocket experiments would have the financial backing of the Army.

Between 1930 and 1932, A-1 was designed and built at Kummersdorf. It weighed about 330 pounds, but was not properly balanced and failed to fly. While Dornberger worked at ironing out A-1‘s problems, von Braun developed the A-2 with an independent team. This was a liquid-fueled missile stabilized by a gyro-mechanism. It reached an altitude of 7,000 feet in December 1934.

Misfired Rockets Could Result in Civilian Casualties

Although A-2 was a success, it was nothing more than an experimental rocket, too small for military use. Next to be built would be the larger, heavier A-3. But Kummersdorf was too large a city for the testing of this new missile. A misfire might cause an accident in a residential district, and might result in civilian deaths. Also, there would always be watchful eyes keeping track of the rockets, keeping an eye on the test center.

By the beginning of 1935, Adolf Hitler had been in power for two years. On his orders, all military trials were to be conducted in the strictest of secrecy. Another site would have to be found for testing the rockets.

Von Braun remembered that his mother used to mention an island off the northern coast of Germany, in the Baltic Sea, called Usedom. Her father used to hunt ducks there. The way his mother described the island, it sounded like the ideal place for missile tests—by a seacoast, and secluded. Late in 1935, von Braun visited the island. It was densely wooded and sparsely populated, and the Baltic Sea offered a 300-mile-long range for test shots. Both Dornberger and von Braun decided that Usedom would be perfect.

The Wehrmacht, the rejuvenated German Army under Hitler, and the Luftwaffe jointly purchased the island’s northwestern peninsula in 1936. During the following year, the missile test center was built—wind tunnels, test stands, power stations, and workers’ housing—all in strictest secrecy. This construction took place near the former fishing village of Peenemünde.

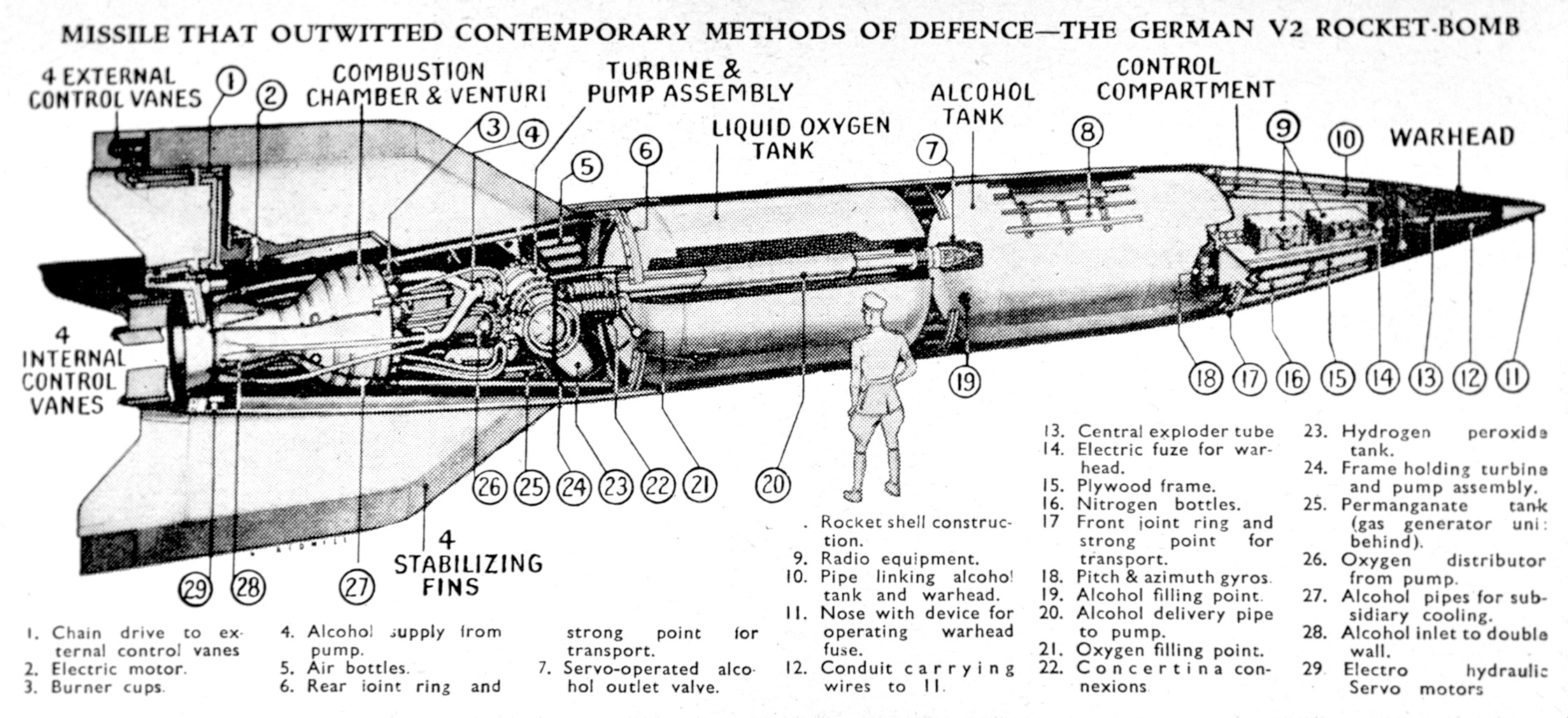

While the Peenemünde base was under construction, work on the rockets continued. The third experimental rocket, A-3, was tested throughout 1936 and 1937, and a great deal was learned about gyro-mechanism and stability from this temperamental missile. By autumn 1939, a military rocket called A-4 was on the drawing board.

Adolf Hitler had never been terribly enthusiastic about rockets. His military advisers thought that A-4 was nothing but an exotic toy, requiring a lot of money—each cost about $25,000. In late 1939, with his panzer units preparing for a spring offensive, Hitler was not convinced that A-4 should ever go beyond the conceptual stage. In the spring of 1940, the Wehrmacht rolled through Belgium, Holland, and France in six weeks, and waited at the edge of the English Channel for the order to invade Britain. With the war going so well, it looked as though the rockets would not be needed.

But the Luftwaffe lost the Battle of Britain, and the A-4 project was given top priority. Test firing of the rocket began in March 1942 with results, however, that did nothing to bolster Hitler’s confidence. The first A-4 blew up. Three months later, a second rocket rolled and twisted crazily after lift-off and crashed into the Baltic Sea. Two months after this, another A-4 blew up shortly after launch.

Finally, on October 3, 1942, the fourth A-4 performed the way the scientists hoped it would. The black-and-white painted missile made a graceful ascent from its launch stand, performed flawlessly throughout its flight, and splashed down on target in the Baltic, 118 miles away. The launching was filmed by a battery of cameras, which caught the dramatic lift-off from several different angles. Both Walter Dornberger and Wernher von Braun breathed a sigh of relief. There was still a lot of testing to be done, but at least they now had one success they could build on.

Hitler’s Ominous Dream

While the testing went on, neither Dornberger, now a colonel, nor von Braun heard anything from Berlin, which was all right with them—no news was good news. But one day in March 1943, Munitions Minister Albert Speer arrived in Peenemünde and dropped a thunderbolt. Speer told Dornberger about a bad dream Hitler had concerning the missiles—he dreamed that no A-4 would ever reach England. The rocket program was in danger; Hitler’s dream would be excuse enough to cancel everything.

Speer was in favor of the project, which was one reason why Hitler had not called it off already. Both Dornberger and von Braun feared that Hitler might one day cut off all funding for their research, for some idiotic reason or maybe no reason at all. So they decided to do something to help their own cause.

On July 7, 1943, Dornberger, von Braun, and another technician boarded a Heinkel He-111 bomber and flew to Hitler’s “Wolf’s Lair” in East Prussia. They brought along scale models of launchers and colored graphs and drawings. As the pièce de résistance, they also took a color film of the previous October’s successful A-4 launch.

Along with members of the High Command, Hitler inspected the models and drawings. Wernher von Braun personally narrated the film, describing every point and detail with infectious enthusiasm. The film began with the 46-foot-long missile being wheeled to its launch stand, then showed the prefiring preparations and, as the climax, ended with the launch.

White and yellow flame billowed from the A-4’s stern. Slowly at first, but with increasing speed, the missile began to rise. The cameras followed the ascent and stayed with the rocket until it punched through the white layer of overcast, traveling faster than sound.

Dornberger and von Braun had designed the film for dramatic impact, and it certainly did its job. After the lights came back on, Hitler sat still for a moment. Then he stood up, shook hands with the three rocket men, and actually thanked them for their work. A moment later, he came close to apologizing for not having recognized the rocket’s potential earlier, declaring that there would have been no war in 1939 if he had had long-range guided missiles.

The demonstration accomplished what von Braun and Dornberger wanted. The rocket program was once again given top priority. Late in 1943, the A-4 went into mass production.

The Secret A-4 Project & Its Thousands of Laborers and Technicians

While all the testing was taking place at Peenemünde, Allied intelligence was slowly becoming aware that something was going on. With a program as large as the A-4 project, which involved thousands of people—laborers, technicians, clerks—it was impossible to keep things a secret forever. Word was bound to leak out eventually.

Indeed, early in 1943 Polish manual laborers at Peenemünde began noticing an occasional heavy, vibrating noise from the northwest part of Usedom Island. The men talked about what they had seen and heard among themselves. Eventually, the stories got around to another Pole, who brought food and supplies over from the mainland. When he left the island, he mentioned the stories he had heard about the mysterious goings-on. The story spread, and word began to drift around in bars, in shops, and on the street. Eventually, the story reached a member of the Polish Underground.

Other messages were received in London from scattered sources—underground units in occupied Europe, intelligence agents inside Germany—that kept mentioning secret weapons and Peenemünde. The War Office Intelligence Branch appointed 35-year-old Duncan Sandys to investigate the possibility of long-range rocket development. By June 1943, Sandys was shown aerial reconnaissance photos of Peenemünde taken by an RAF Mosquito airplane. The photos clearly showed two A-4 rockets, which were lying on their sides in the open. Thus Sandys had visual, concrete proof that rockets were being tested at Peenemünde. He recommended that a bombing strike be carried out against the missile base as soon as possible.

Thus, on the night of August 17, 1943, 597 Lancaster and Halifax bombers toggled their loads over the rocket center. But although the bombs churned up an impressive amount of rubble, most of the bombs fell on the technicians’ housing. The explosions killed 750 people, but 650 of these were Polish laborers and Russian prisoners of war. In a clever gambit, Walter Dornberger, by now a major general, decided to leave the bomb damage in place to fool Allied reconnaissance planes. The ruse worked—Allied bombers did not return for nine months.

Testing continued at Peenemünde, but the equipment and means of manufacturing the A-4 were moved into a huge, complex network of tunnels beneath the Hartz Mountains in central Germany. Inside the mile-long bombproof tunnels under the mountains, production proceeded apace. These “Nordhausen works” were capable of turning out 700 A-4 rockets every month. The organizers set up another testing center at Blinza in Poland, and connected it with Nordhausen by a rail link. Along with the scientists and technicians, the launching units that would fire the A-4 at enemy targets were stationed at Blinza. There were three such units, each having names that made them sound like nothing more than conventional artillery units to fool enemy intelligence: 836 (Mobile) Artillery Detachment, 444 (Training and Experimental) Battery, and 485 (Mobile) Artillery Detachment.

These units made use of simple test stands that could be set down on any level stretch of ground—even the middle of a roadway—to support a launch. They were so simple and mobile that their crews would be able to set them up, launch their rocket, and take them down again all before Allied fighter-bombers could find them. The launching crews were fully trained and ready for operations by June 1944. But the rockets themselves were not ready until the end of August—General Dornberger and Wernher von Braun estimated that over 65,000 changes had been made in the A-4 design since the project began.

Once the rockets had finally passed their tests, however, the launching crews were moved into positions for firing on London. By September 7, all three units were ready. The men of 485 (Mobile) Artillery Detachment and their nine launching units set up camp near The Hague, Holland, just under 200 miles from London.

Literally Unstoppable…

From his home in The Hague, 14-year-old Hans van Wouw Koeleman ran outside when an unusually loud roar flooded his house. Young Hans thought that the noise was made by some new kind of German or Allied plane but, instead of airplanes, he spotted the long shapes of two A-4 long-range rockets rising straight up, “just before they hit the cold air and contrails were formed.” These two had been launched simultaneously from Wassenaar, just northeast of The Hague, by 485 Detachment. Hans recalls that “the thunder of the rocket engines was tremendous.”

The double launching took place at 6:39 pm London time. Only five minutes would pass before the first rocket slammed into Staveley Road, Chiswick, traveling at nearly 5,000 miles per hour. Dr. Josef Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry soon rechristened the A-4. The rocket would become known as “V-2”—for Vergeltungswaffe, or Vengeance Weapon. (The V-1 was the Flying Bomb, a primitive, pilotless jet plane that had been launched against London during the summer of 1944.)

On March 27, 1945, a V-2 scored a direct hit on a block of flats in Stepney, East London, collapsing the building and killing 134 Londoners, with another 49 injured. About two hours later, the last V-2 to come down on Britain landed in Orpington, Kent, about 20 miles southeast of London. The war would be over in just over five weeks.

Between September 8, 1944, and March 27, 1945, 517 V-2 rockets struck London, with another 378 falling short and exploding in Essex. Throughout southern England, a total of 1,054 came down. In London alone, the rockets killed more than 2,700 civilians. Industry suffered considerable loss and morale, especially in London. Another struck in and around Antwerp, which the Germans targeted for being a major port of Allied supplies to their troops on the Continent. Brussels was also a target; thousands of Belgians were killed by V-1s and V-2s.

The V-2s were literally unstoppable: They traveled with the velocity of a rifle bullet, and could not be seen, let alone destroyed. They exploded on their targets before the sound of their travel arrived. Like Robert Stubbs, their victims had no idea they were about to be blasted.

Had these weapons been available earlier in the war, they might well have had the effect Hitler intended—turning the tide in his favor. The only reason the launchings ended on March 27 was because General George S. Patton’s troops were close to overrunning the launching units.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments