By Robert Heege

Wu Hsu was having trouble sleeping. As the taotai, or mayor, of Shanghai, Wu was charged with the ultimate welfare of China’s greatest cosmopolitan city. Complicating matters was the fact that, in addition to the Manchu emperor and his palace minions in Peking, Wu had to answer not only to the ordinary Chinese citizens, but also to a host of “foreign devils” as well. Thousands of British, American, French, and other European nationals had come to China in the wake of the Second Opium War of the 1850s and stayed on to become an ever-increasing presence in the city.

Rattling sabers perpetually on behalf of the foreign nationals was the military muscle of their respective governments, particularly the British, who had already forced the Chinese to cede the port of Hong Kong to Queen Victoria at the end of the First Opium War in 1842. The British continued in the years following the Second Opium War to drool at the prospect of wrangling even more territorial and commercial concessions from the Manchu emperor in Peking.

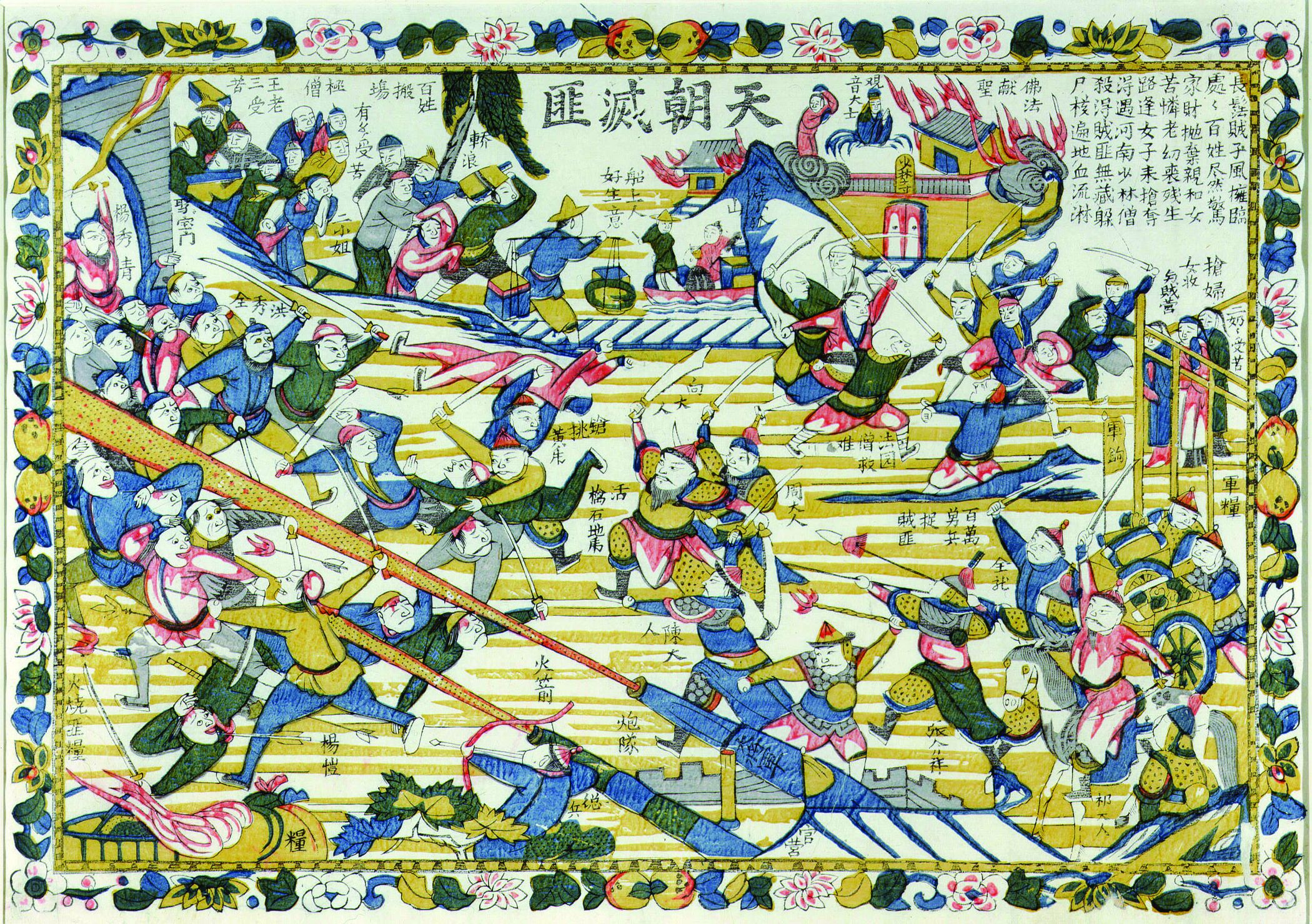

Unfortunately for Wu, just such a pretext was forming on the horizon in the form of a bloodthirsty cohort of bandits, river pirates, anti-Manchu insurgents, and pseudo-religious fanatics known as the Taipings. The Taipings, whose name, ironically enough, means “heavenly peace,” had been roaming the Chinese countryside virtually unchecked for nearly a decade, with the stated objective of driving out the Manchu rulers and all other “devils”—foreign or otherwise—from Chinese soil. Millions had died in one of the bloodiest civil insurrections in world history.

Coming on inexorably like a swarm of locusts, the fearsome Taipings overran village after village, swallowing up broad swaths of real estate and putting untold numbers of people to the sword. Those who survived the initial massacres were subjected to a draconian fundamentalist regime, where the use of alcohol, tobacco, or opium warranted an automatic sentence of death by decapitation. Sex was outlawed as well, even among married couples. Those who were found in violation were beheaded side by side. All of this was according to the half-baked teachings of their leader, Hong Xiuquan, a lunatic mystic who preached an odd blend of Confucius and the New Testament. Hong had somehow managed to convince himself that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ.

The Taipings, who had already seized the old Imperial capital of Nanking, were reported to be working their way toward the outskirts of Shanghai. The foreign merchants promptly formed a delegation and demanded that Wu do something about the Taipings before they destroyed the lucrative import-export trade. That something, as it happened, turned out to be embodied by one 29-year-old American adventurer named Frederick Townsend Ward.

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1831, Ward had been a rebel of a different sort. After leaving school at the tender age of 16, Ward was well on the way to becoming what later would be called a juvenile delinquent. His exasperated father, a wealthy ship owner, prevailed on a family friend, the commander of a clipper ship called the Hamilton, to take the incorrigible youngster into his charge and make him a man. In due course, Ward found himself at sea, serving as second mate under the watchful eye of the ship’s captain, William Allen.

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1831, Ward had been a rebel of a different sort. After leaving school at the tender age of 16, Ward was well on the way to becoming what later would be called a juvenile delinquent. His exasperated father, a wealthy ship owner, prevailed on a family friend, the commander of a clipper ship called the Hamilton, to take the incorrigible youngster into his charge and make him a man. In due course, Ward found himself at sea, serving as second mate under the watchful eye of the ship’s captain, William Allen.

In 1847, Hamilton sailed from New York to Hong Kong, which was still under Chinese control at the time. This was Ward’s first glimpse of China, but it is unlikely that he saw much more than the port area itself, as the Chinese government severely restricted the movements of all foreigners within its precincts. Two years later, Ward was back in New England, where he enrolled in the American Literary, Scientific and Military Academy in Vermont. He did not last long. Within months he was at sea again, a first mate this time, aboard another clipper, the Russell Clover. On this trip, the captain was Ward’s own father.

Ward’s time at the academy in Vermont had been short, but the courses on military strategies and tactics struck a chord in the restless young man. No sooner was he back on dry land than Ward began exploring prospects as a professional gun for hire—not as a desperado but as a proverbial soldier of fortune. By the early 1850s, Ward was operating south of the border in Mexico, under the command of the infamous Tennessee freebooter, William Walker, whose mercenary army later succeeded in briefly conquering Nicaragua. From Walker, Ward gained valuable insight into the practice of recruiting, training, and commanding men-at-arms.

In 1854, when Britain and France went to war against Russia in the Crimea, Ward sailed for Europe, where he promptly secured a commission for himself in the French Army. The indiscriminate slaughter in the Crimea, where whole regiments were routinely blown to bits charging into the teeth of entrenched artillery fire, made a deep impression on the young New Englander. Shortly before the cessation of hostilities in 1856, Ward’s rebellious streak reemerged in a dispute with a superior officer, and he was obliged to resign his commission after being charged with insubordination.

The next year, armed with an unusually varied résumé, Ward made his way back to China, intent on seeking his fortune as a mercenary. Unfortunately, nobody took him up on the offer, and he was obliged to fall back on his nautical experience, serving a brief stint on a coastal steamer before returning home to man a desk in his father’s office. Soon after arriving stateside, however, Ward’s wanderlust took hold again. Before long, the young shipping agent was tucking away his paychecks, secretly scheming for another go at the mercenary game.

Somehow, Ward managed to convince his father that opening a trading office in the Far East would be an easy way to line his pockets. In 1860, accompanied by his brother, Ward disembarked at Shanghai. Almost immediately he deserted his sibling, who was left to set up the family business by himself, and began searching around for a more exciting way to make a living. This time Ward had better luck, securing a position as first mate aboard Confucius, an armed riverboat whose captain was a fellow American. Confucius was engaged by the elaborately named Shanghai Pirate Suppression Bureau and charged with protecting commerce along the Yangtse River and the waters off Shanghai. One of the bureau’s chief organizers was the mayor of Shanghai, Wu Hsu.

Ward reveled in the chance to put his seafaring skills and military experience into action. He quickly began making a name for himself, battling river pirates for the bureau. Word of the American newcomer’s fearlessness and ability to work well with his Asian crew members reached Wu at the same time that the Anglo-European delegation began complaining about the uncomfortably close proximity of the Taiping rebels. Ward was openly advertising himself as a gun for hire, prompting Wu to seek out the mysterious mercenary from Massachusetts. Having no faith in the miserable track record of the Chinese army, the wily taotai offered Ward the chance to recruit, train, and command a private militia composed entirely of westerners to defend his city against the Taipings.

Like many Chinese, Wu was dazzled by western technology and military might and believed that the westerners were innately superior to the more backward Asians. Westerners in China naturally did everything they could to encourage this view. Wu’s scheme specifically depended on raising an army of Europeans that would fight and defeat the dreaded Taipings. Ward jumped at the chance but also drove a hard bargain. He demanded a king’s ransom of $500 a month for himself, $200 for his officers, and $50 for each private, plus a negotiated bounty in cash for any towns he might liberate. Risking the wrath of the emperor, who was loath to admit that he might need foreigners to fight his battles for him, Wu discreetly agreed to Ward’s terms. The bargain was sealed.

Backed by large amounts of Chinese silver generously supplied by the deep pockets of Wu’s patrons, the bankers of Shanghai, Ward spent the spring of 1860 stockpiling the best weapons money could buy. He was a shrewd judge of firepower. When the time came to fight, Ward’s men would be armed with 1851 U.S. Navy Colt revolvers and Sharp’s famed breechloaders, the most advanced rifle of the day. He combed the city, searching for Americans or Europeans with any military experience. Even with the kind of wages he was offering, it was difficult for Ward to find anyone willing to face the fearsome Taipings.

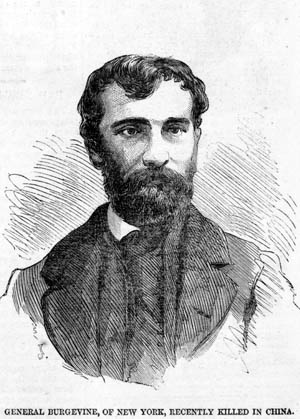

Ward was reduced to dredging the bars and docks of Shanghai for any human flotsam he could find. He recruited 100 men, Americans mostly, including a South Carolinian named Henry Burgevine, but there were also Britons, Germans, Frenchmen, and a host of others from the various European states. Officially, they were known as the Shanghai Foreign Arms Corps. Their leader, characteristically, preferred to call them the Ward Corps. The men themselves, a motley collection of cashiered seamen, wharf rats, and drunken derelicts, did not care what they were called as long as they were paid.

In the summer of 1860, Ward’s boot camp was barely in operation before Wu and the other financial backers of the enterprise became apprehensive. They demanded that Ward accompany the Imperial forces on a scouting mission to see how close the Taipings were getting to Shanghai. They were quite close, indeed, as it turned out, and the Ward Corps helped to liberate two nearby towns from the Taiping yoke.

Wu was so delighted with this initial success that he got carried away, tasking Ward with expelling the Taipings from the nearby city of Sung-chiang as a follow-up. Ward carefully explained to the taotai that his embryonic force had been extremely lucky and that his men, although armed to the teeth, were still scarcely half trained. Moreover, the Taipings had turned Sung-chiang into a veritable fortress. Ward knew from his experiences in the Crimea that assaulting fortifications without artillery was suicidal. Wu, however, remained sanguine in the face of Ward’s apparent modesty and would not be dissuaded. Against his better judgment, Ward, all too aware that he was in his paymaster’s silken pocket, reluctantly agreed to give it a try.

The Ward Corps, still drunk with victory, set off in the dead of night for Sung-chiang. Unfortunately, they were literally drunk as well. Ward had hoped to rely on the element of surprise to carry the day, but many of the troops were as overconfident of their martial prowess as the taotai himself. The sound of their impending approach alerted the Taipings, who were wide awake and waiting for them when they got there. As soon as Ward’s men staggered into range, the Taipings opened up, routing the column, which broke and ran all the way back to Shanghai. Ward had been in China long enough to know the importance of not losing face.

Back in Shanghai, he paid off most of the drunken survivors, weeding out the incorrigible and immediately beginning a new recruiting drive. This time, his seafaring experience provided an inspired idea. Ward began canvassing for recruits in the small Filipino community in the city. As a former seaman, Ward knew that the “Manilamen,” as they were called, were highly prized by American captains, who had been employing them on their merchant ships and whalers for years. To a man, the Filipinos were industrious, hard-working, loyal, and quick to learn. They were also fluent in Spanish, a language Ward had mastered during his time with Walker. Ward was convinced that he could teach them to be proper soldiers.

Over the next few weeks, Ward added 80 Manilamen to his reconstituted corps and managed to keep Wu at bay until he was satisfied that his soldiers’ training was complete. He also bought some artillery, adding several field pieces to his arsenal. To teach his men how to use the new cannons, he enticed deserters from the British Army and Navy to instruct them, paying them handsomely for the benefit of their expertise. By the middle of July, Ward felt that his forces were ready to make a second run at Sung-chiang. This time, he left nearly all the Americans and Europeans behind.

He boarded a coastal steamer with about 200 of his Manilamen and sailed well past Sung-chiang. They disembarked and stealthily made their way back over land, manhandling a couple of cannons to a rendezvous point, where they were to lead the attack in a coordinated effort with the Emperor’s army. As the Imperial troops watched, Ward’s men, bringing their cannons under the noses of the enemy, crept unnoticed all the way to a moat surrounding the city. The Taipings had no idea they were there until Ward’s gunners blew the city’s eastern gate to smithereens and rushed in, only to be confronted by a second, interior gate.

With the Taipings firing down at them from above, Ward and his Manilamen braved a murderous fusillade to place several kegs of gunpowder against the interior gate. Meanwhile, Ward’s artillery began blasting away at the Taipings on the wall with canister, decimating them with hot shrapnel. Ward, still under fire and armed only with the rattan walking stick he had recently begun sporting, personally set off the huge gunpowder charge against the gate. The explosion rocked the earth, knocking attackers and defenders alike to the ground, but it only managed to blast a hole large enough for a single man to squeeze through. Ward clambered to his feet, waving his stick wildly, and ran forward, shouting at the top of his lungs, “Come on boys, we’re going through!” Hurling himself forward, he disappeared through the hole. Burgevine, the South Carolinian, and Vincente Macanaya, one of the first of the Manilamen to join the Ward Corps, did likewise. One by one, the rest of the Filipinos surged through the tiny gap.

Ward, now wounded, led his men to the top of the walls, where they poured lead into the Taipings with their breechloaders. After a vicious struggle, they succeeded in capturing the enemy’s cannons. Moments later, the Taipings below the walls found themselves being bombarded by their own artillery. Ward set off a rocket to signal the Imperial troops beyond the walls, but they stayed where they were, safely out of harm’s way, leaving Ward and his men, outnumbered 5-to-1, to fight for their lives against the maniacal Taipings. When it was over, the city looked like a butcher’s yard. Against all odds, Ward and his Manilamen had prevailed, but their victory cost them dearly. Out of 200 men, 62 were killed and another 100 were wounded. As they convalesced, they consoled themselves with the fact that the fortune in gold, silver, and precious jewels that they seized at Sung-chiang had made them all wealthy men.

Wu was delighted by the turn of events. The white merchants and businessmen of Shanghai, however, were beside themselves with worry. While they had pressured Wu to do something about the Taipings’ steady advance toward the city, they had expected merely a truce or a more vigorous response from the Chinese Army. Wu’s solution to the problem gave them fits. Although the Taipings had made life miserable for the Chinese, they had always taken pains never to act with hostility against the westerners. This unspoken neutrality had continued in force for years. As a westerner fighting for the Chinese, Ward had upset the delicate balance between the foreigners in China and the Taipings. If the rebels associated the upstart American with the western merchants and retaliated against them, the entire China trade might go up in smoke.

Wu was delighted by the turn of events. The white merchants and businessmen of Shanghai, however, were beside themselves with worry. While they had pressured Wu to do something about the Taipings’ steady advance toward the city, they had expected merely a truce or a more vigorous response from the Chinese Army. Wu’s solution to the problem gave them fits. Although the Taipings had made life miserable for the Chinese, they had always taken pains never to act with hostility against the westerners. This unspoken neutrality had continued in force for years. As a westerner fighting for the Chinese, Ward had upset the delicate balance between the foreigners in China and the Taipings. If the rebels associated the upstart American with the western merchants and retaliated against them, the entire China trade might go up in smoke.

For the Chinese population of Shanghai, however, the Ward Corps had become heroes. Hundreds of new recruits flocked to join them. As for the Taipings, their leaders reluctantly realized that a new and deadly enemy had been sent against them. Hong Xiuquan, who as the Taiping’s “Heavenly King” was exempt from the strictures of his own faith, was content to sit things out in his palace at Nanking, fortified by drugs, alcohol, and a steady diet of teenaged girls. The brigands leading his faithful into battle were another story. The Taipings had been organized to function as a regular army of storm troopers, and their generals had picked up a thing or two from Genghis Khan. They knew, even before Ward did, that the next logical place for Wu to send the Ward Corps would be Ch’ing p’u, another glorified blockhouse on the road to Shanghai. On August 2, 1860, when the duly dispatched Foreign Devil and his band slipped silently up to the walls of Ch’ing p’u with their scaling ladders, some of the best fighters in the Taiping army were lying in wait.

As soon as Ward and his Manilamen made it up to the top of the wall, a hail of bullets from every direction swept them off the walls like flies. In a matter of minutes, half the corps was shot to pieces; Ward was hit five times. One of the bullets smashed into his jaw, exiting through his right cheek. Unable to speak, Ward coolly wrote out his instructions, which the young Filipino Macanaya, now his most indispensable subordinate, followed to the letter. Carrying their wounded with them, the corps conducted a fighting retreat, somehow managing to escape the death trap that had been prepared and sprung on them. The ground behind was littered with their dead. The Taiping marksmen had personally targeted the strange white warrior with the walking stick. He would bear the scars from this action for the rest of his life, and his speech was permanently affected. He was lucky to be alive.

The Ward Corps limped back to Shanghai, where Ward and the other wounded received medical treatment for their injuries. While they were in the hospital, the Taipings besieged Shanghai. They had succeeded in penetrating the city’s precincts when they received word from their Heavenly King to halt their siege and proceed immediately in the opposite direction, to join battle with Imperial forces coming down from Hunan in the north.

Wu, who had grown quite fond of Ward (as had Wu’s daughter), arranged to have him secretly invalided out of Shanghai for further medical treatment by western doctors. Ward returned to the city in the spring of 1861, intent on rebuilding his beloved corps. The moment he set foot in port, however, the British arrested him and prepared to hand him over to American authorities for deportation. To their surprise, they discovered that Ward had obtained Chinese citizenship. Unsure of what to do, the British took him aboard one of their warships in the harbor and kept him there. Fortunately for Ward, he managed to get word to the ever-faithful Macanaya, waiting in port. Under cover of darkness, Ward somehow squeezed through a porthole, slipped unseen into the water, and swam a short distance to Macanaya, who was waiting in a skiff.

Once back on land, Ward gave the British a wide berth and began building up his forces in earnest. After taking another unsuccessful crack at Ch’ing p’u, he approached Wu with a bold new scheme. To the delight of the taotai, Ward proposed to equip, train, and mobilize an enormous military machine, a true western-style army composed almost entirely of Chinese troops. Ward was confident the Chinese would flock to his banner.

Ward had become ever richer through a number of sweetheart business deals with Wu. He poured the money into more artillery, high-end arms such as Dreyse “needle guns” from Prussia, vast quantities of ammunition, and other military matériel. By this time, Wu had used his connections to get Ward commissioned a full colonel in the Imperial Army. Keeping a personal bodyguard of 200 Manilamen commanded by Macanaya, Ward outfitted his new recruits in European-style uniforms topped with turbans inspired by Great Britain’s Indian forces. In a matter of months, Ward’s forces grew to some 7, 000 men. They carried their own colors, an elegantly simple banner upon which was inscribed the Chinese character, Hua. This was the closest the men could come to pronouncing their commander’s name.

As the new year of 1862 dawned, Ward announced that his army was ready for action. It was none too soon. With the winter snows, the dreaded Taipings had returned with a vengeance. At Wu-sung, about 25 miles from the approaches to Shanghai’s harbor, they began digging trenches and revetments with the aim of cutting off trade and isolating and taking the city. Suddenly, the sound of bugles was heard in the distance. The Taipings looked up to see what appeared to be a huge European army marching toward them. Then they saw Ward’s banner fluttering in the wind.

The air was rent by rifle fire. Moments later, mortar rounds and artillery shells began slamming into the Taiping trench works. The rebels who survived the encounter ran for the hills. Barely a week later, Ward and a small strike force of 500 handpicked men took the city of Kwang-fu-lin from a Taiping force of several thousand, who again broke and ran. Ward was promoted to general—even the British were won over. Ward became a full-fledged mandarin and returned to Shanghai to marry Wu’s daughter.

Shortly afterward, Ward took his men back to the scene of their earliest victory. In the vicinity of Sung-chiang, they went toe to toe with the entire Taiping army, which was hell-bent on retaking the city and the surrounding towns. Ward’s men blasted the Taipings to pieces. Even Ch’ing p’u, the prize that had eluded them for so long, fell at last to the man from Massachusetts. As for Ward, he was wounded five more times during the bloody engagements; one of his fingers was shot off. Despite his wounds, he must have thought he would live forever.

In March 1862, the Ward Corps was officially rechristened the “Ever-Victorious Army” by the grateful Manchu government. Ward received a further honor when he was created a Mandarin Third Rank by Imperial decree. His reputation and string of victories continued to grow, and by the summer of 1862, it was clear that the Taipings, while not yet completely defeated, were fast becoming a spent force.

Ward began making plans for an assault on Nanking, the Taiping rebel capital, augmenting his army with armed riverboats to ferry his men wherever they were needed and enough mobile field pieces to create a complete artillery corps. But the Manchu emperor, no longer living in fear of the Taiping threat that had plagued him for years, began to worry that Hua might be becoming too powerful a figure on the Chinese landscape. The fact that Ward resolutely refused to shave his forehead and sport a long braided queue, and continued to favor western clothing over the opulent Mandarin robes he was privileged to wear, irritated many at the court.

On September 20, 1862, Ward was characteristically at the head of his beloved troops, leading a coordinated attack that pitted British, French, and Imperial Chinese forces against one of the last Taiping strongholds, the city of Cixi. At the base of the city’s walls, Ward suffered his 15th and final wound. Shot through the stomach, he refused to leave the battlefield until he collapsed and was carried from the field by his weeping soldiers. He lingered for two days on a British gunboat, calmly dictating his will. After making provisions for his brother, his sister back in Massachusetts, and his adored Chinese wife, Ward succumbed in the early morning hours of September 22, two months shy of his 31st birthday.

After Ward’s death, the Chinese gave command of the Ever-Victorious Army not to Macanaya, as he had wished, but to Ward’s erstwhile second in command, Henry Burgevine. The South Carolinian immediately betrayed Wu’s trust by attempting to rob him, and he had to quit China under pain of death. To replace Burgevine, the British offered up a lackluster officer named John Holland, whose chief qualifications seemed to be that he was British and hated Americans. Eventually, they settled on a reasonably efficient plodder named Charles George Gordon.

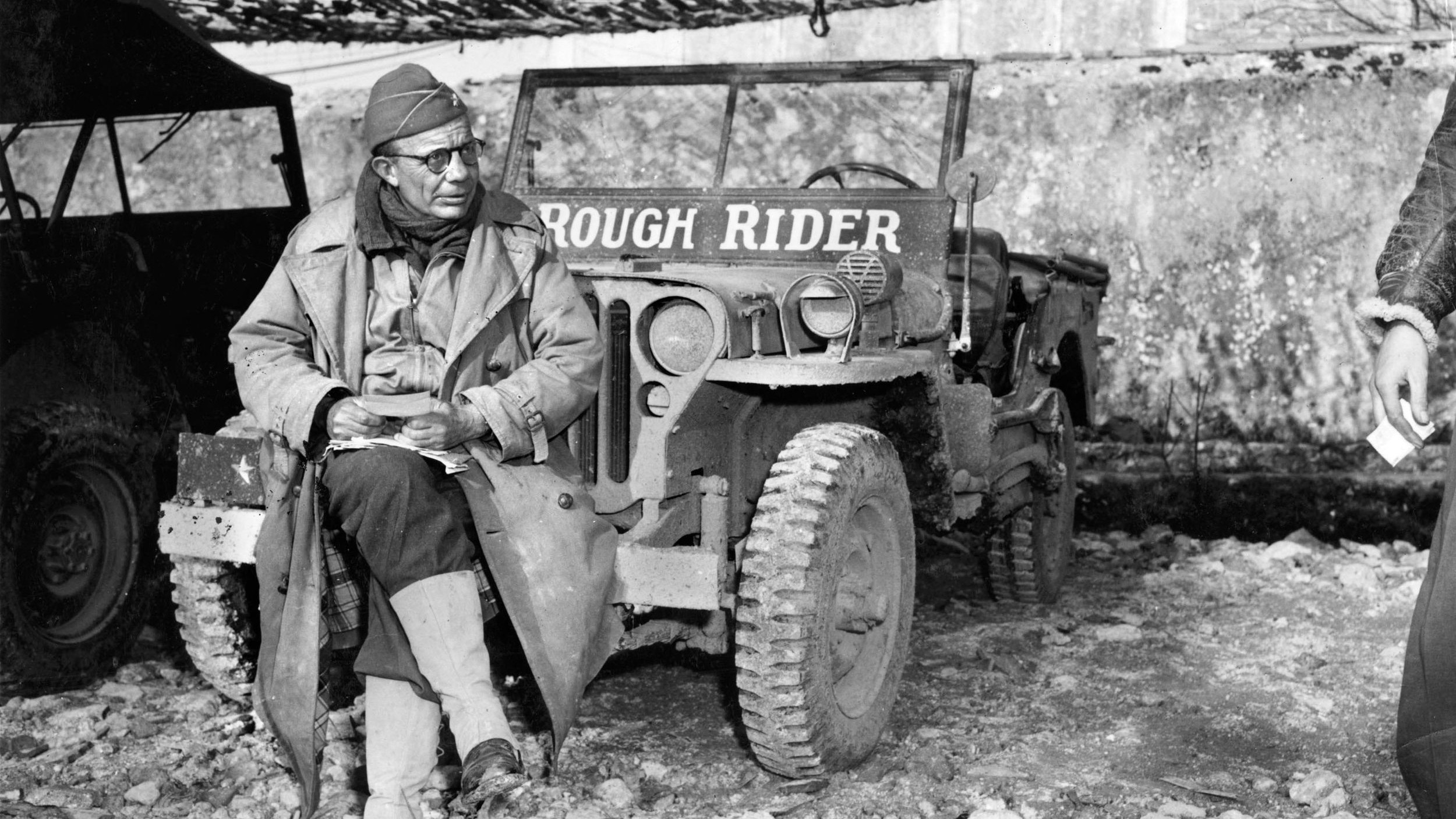

By then, most of the heavy lifting had already been done. The Chinese government officially disbanded the Ever-Victorious Army 18 months before the Taiping rebellion finally came to an end. That did not stop the British from crediting Gordon with nearly all of Ward’s victories, heaping upon Gordon the laurels that rightfully belonged to a dead man. Indeed, he would be hailed as “Chinese” Gordon for the rest of his life, which ended in the Sudan 20 years later when Gordon was spectacularly beheaded by Muslim followers of another would-be son of God, the so-called Mahdi.

As for Ward, he was quickly and almost completely forgotten in the West. In China, however, he was still remembered, prayed to, and revered as Hua, the Confucian demigod who had redeemed their lost honor and showed the Chinese people how to fight. Ironically, it was an admirer of the Taipings, Mao Zedong, who effaced Ward’s memory. After leading the Chinese Communists to power in 1949, Mao had Ward’s remains dug up and his gravesite bulldozed and paved over. Ward’s bones—and memory—have been missing ever since.

A bit of anti British prejudice, I fear. No one could EVER describe Gordon as a plodder. His motives and actions in China were utterly honourable (honestly, Ward’s might in some lights be described as decidedly questionable) so I don’t really think it at all helpful for you to try and decry his time in China. Gordon, after all, himself gave Ward the honours and accolades that he believed were due to him.

Thank you. Rant over.

Duncan