By Eric Niderost

On November 9, 1775, a British resident of Quebec wrote a letter back home, a missive that he knew might not even reach England, because the Canadian fortress city would soon be under a state of siege. A bedraggled band of Americans under Colonel Benedict Arnold had recently arrived outside the gates, he said, determined to make both the city and Quebec province the so-called 14th colony in their fledgling rebellion against the British crown.

The writer had little sympathy with the patriot cause, but the sheer magnitude of their feat won them a grudging admiration. “There are about 500 provincials arrived on Pointe Levi opposite the town,” he began, referring to the American revolutionaries, “by way of the Chaudière [River], across the woods.” The author still could not believe that they were there, and the rest of the passage is filled with a genuine sense of awe. “Surely a miracle must have been wrought in their favor…. They travelled through woods and bogs, over precipices for the space of 120 miles, attended with every inconvenience and difficulty.”

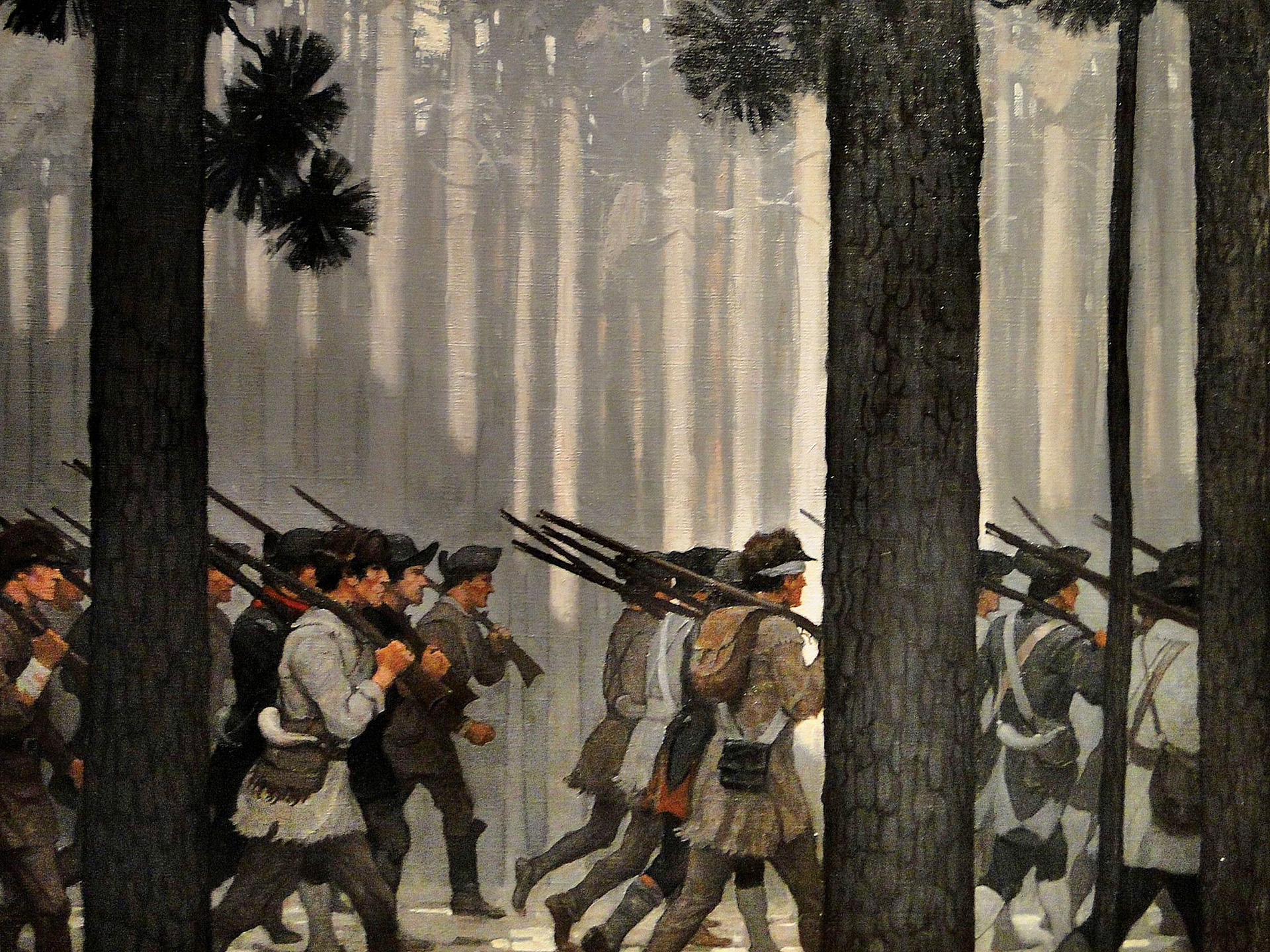

The description is accurate, but barely scratches the surface of the trials and tribulations that attended the long and agonizing march to Quebec. Arnold and his men had been soaked by torrential downpours of rain, half-blinded by raging snowstorms, frozen by plummeting temperatures, and exhausted by the hard physical labor of carrying heavy bateaux on portages that were little better than viscous bogs.

Sickness and starvation also assailed them, and some lacked the proper clothing for the onset of winter-like weather. By the time they reached Quebec, ragged and reduced in numbers, they were little better than emaciated scarecrows. The Americans had reached their objective and had overcome countless obstacles and hardships on their grueling wilderness trek. The completion of such a perilous journey was in and of itself a kind of victory, but it was just the prologue of a drama that was about to unfold in the coming months.

The idea of making Canada an ally against the British was not a quixotic as it might have seemed at the time. Canada had once been a colony of France, part of a Gallic empire based in large part on the fur trade. The French were decisively defeated in the Seven Years’ War of 1756-1763 and had ceded Canada to Great Britain, but 80,000 Quebecois, Gallic in culture and speech, remained in Canada.

The British crown did its best to reconcile the Quebecois, even granting them the right to continue to practice their Roman Catholic religion. Nevertheless, French Canadian resentment was never too far below the surface. It was a smoldering ember that might be fanned into open rebellion. But would they make common cause with the predominantly Protestant 13 colonies to the south, which often expressed distaste for Quebec’s ethnic identity and religion?

Many Americans hoped that the old adage, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” might hold true. Perhaps the French Canadians would let bygones be bygones and let old animosities be forgotten as they took up common cause against the British foe. One of the main obstacles was going to be Brig. Gen. Guy Carleton, the governor of Quebec province. Energetic and resourceful, the 50-year-old British officer was uncommonly sympathetic to the concerns of the Quebecois. Whether that was enough to ensure their loyalty during a determined American invasion was anyone’s guess.

After the clashes at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, an ad-hoc army of Massachusetts farmers hastily gathered together and placed British-occupied Boston under siege. Delegates assembled in Philadelphia to form the Second Continental Congress, and one of its first acts was to adopt the Boston army as the official fighting force of the united 13 colonies. The Second Continental Congress unanimously selected Virginian George Washington as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.

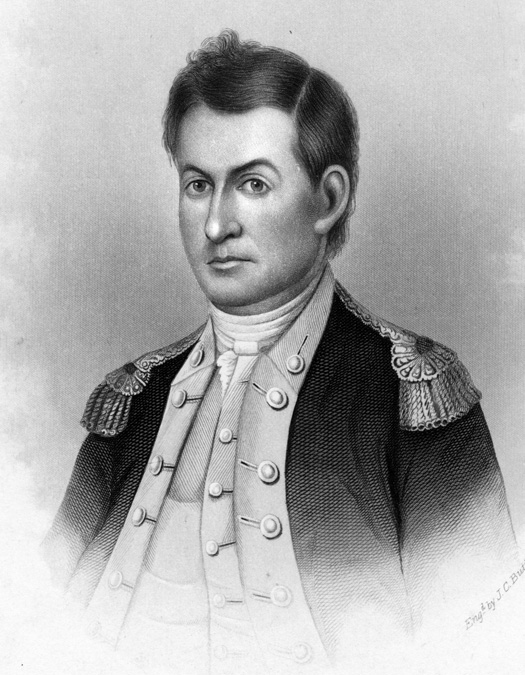

A commanding personality on the scene at the time was Benedict Arnold. A successful businessman who hailed from New Haven, Connecticut, his far-flung trading connections included ports such as New York, Boston, Montreal, and Quebec. By 1775 he was a wealthy man, but as the American Revolution unfolded, he became a fierce partisan of the Patriot cause. Once Arnold committed to the growing revolution, he gave it a dedication so single-minded in purpose it bordered on mania. A human dynamo, Arnold was full of ideas to advance Patriot fortunes.

Canada was a British stronghold, a strategic base from which redcoats could launch invasions to the south. In an age when roads were bad or non-existent, rivers and lakes were natural highways of travel and commerce. Arnold was particularly concerned with the Lake Champlain corridor from Canada, a veritable dagger pointed at the heart of the 13 colonies. Starting from Montreal, a British invasion force conceivably could sail up the Richelieu River and continue on to strategic Lake Champlain. Once the Lake Champlain forts were in their possession, the British could proceed further south to the Hudson River and, ultimately, New York.

Arnold was determined to prevent this nightmare scenario by any and all means at his disposal. Once the British were firmly in control of the Lake Champlain and Hudson corridor, the New England colonies would be cut off from their compatriots further south. Divide-and-conquer would be a winning British strategy. The embryonic United States would never have a chance to be born and prosper.

Arnold acted with customary alacrity, raising a few companies of militia to augment his plans. The initial goal was to seize Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point, which were the two key Lake Champlain strongholds. When he found out that Colonel Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys also intended to take Fort Ticonderoga, Arnold had no problem joining forces with the Vermont militiamen. Ticonderoga quickly surrendered with little resistance, and Crown Point fell into American hands soon after.

Emboldened by these successes, Arnold conducted yet another expedition. In May 1775, he led a raid on Saint-Jean, a Canadian outpost 20 miles southwest of Montreal. One of the prizes of the raid was a 70-ton sloop-of-war that the Americans captured, which deprived the British of a vessel they might have used to ferry their troops across Lake Champlain.

Arnold seemed to be charmed. His successes laid the groundwork for the greatest venture of them all. He hoped to capture Montreal, Quebec, and the rest of British Canada. The capture of Ticonderoga and Crown Point were roadblocks to any British invasion. In Patriot hands, they would delay any southward thrusts by the British, if not entirely thwart them. And taking Canada would eliminate any chance of a landward invasion from the north.

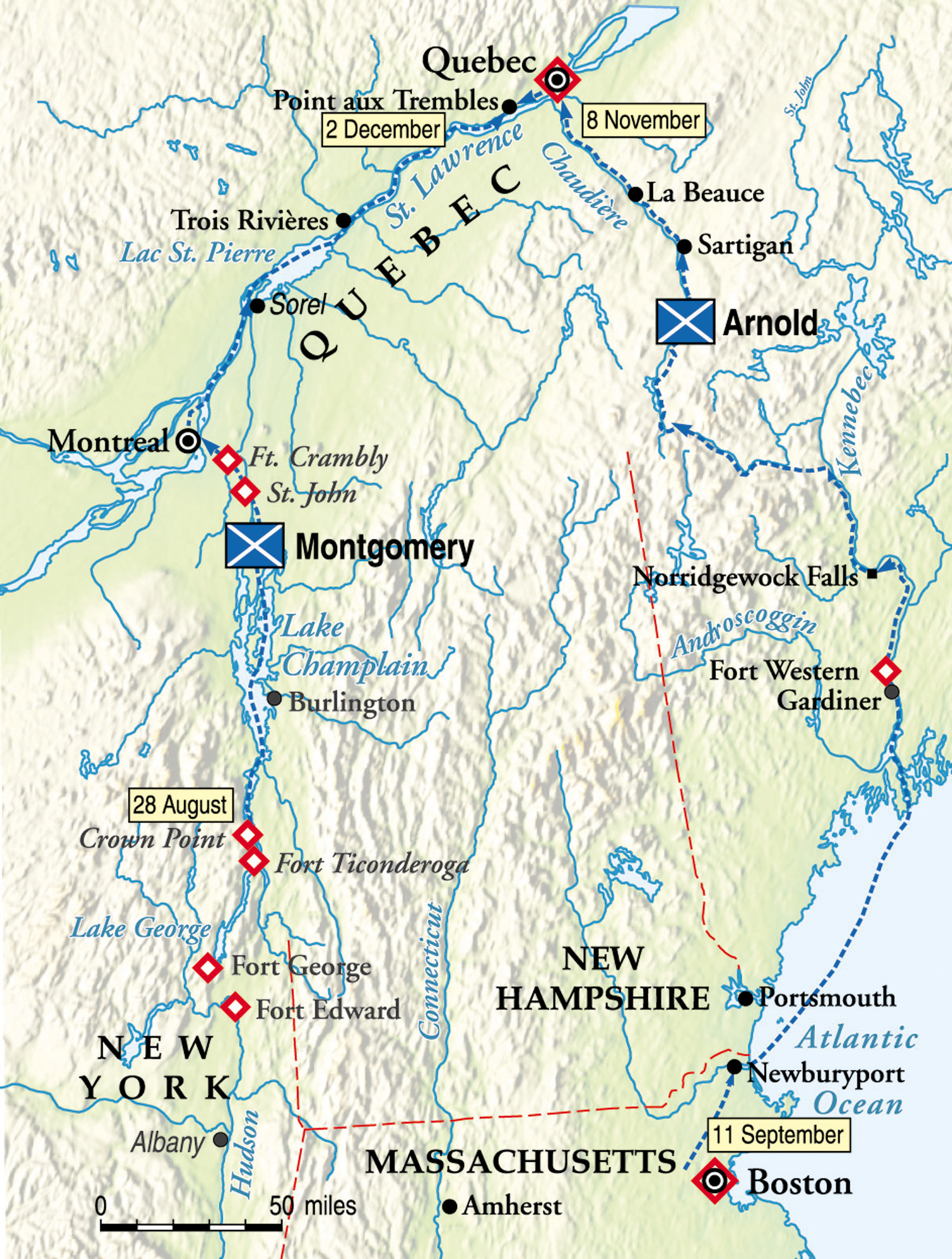

Arnold travelled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to get Washington’s approval for a Quebec campaign. Upon his arrival, Arnold discovered that Quebec was already much on the general’s mind. Indeed, Washington had already ordered Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler to advance up Lake Champlain to seize Montreal and Quebec. His enthusiasm must have been dampened by this news, but Arnold rebounded with a counterproposal. He proposed to Washington two simultaneous campaigns against the province of Quebec that would be mutually supportive.

The proposal would be for a second expedition to sail to Maine and travel north on the Kennebec River. At the time, the province of Maine was part of the Massachusetts colony. The proposed expedition would leave the Kennebec, heading west through a 12-mile section of forest, bog, and lake known to the Indians for hundreds of years as the Great Carrying Place. In this case “carrying” was the operative word because the soldiers would literally have to carry their boats using human muscle, the arduous task being only slightly relieved by brief water passages across three small lakes.

At the end of the Great Carrying Place, the expedition would then travel down the Dead River, so named by the natives for its slow current. Eventually the Dead River would lead them to the Chaudière River and Quebec. It was a simple plan, not without risk, but Arnold was confident of success. The Connecticut colonel was a meticulous planner, seemingly leaving nothing to chance, but his calculations contained errors that almost proved fatal to the entire enterprise.

The wilderness area that the expedition would have to cross was very poorly documented. In 1761, a military engineer named John Montressor had conducted a survey of the Kennebec Valley region, but later events proved his map dangerously flawed. Based on the Montressor documents and other data, Arnold calculated it was 180 miles from Fort Western, which is now the site of the Maine state capital of Augusta, on the Kennebec River to Quebec. In reality, the distance was 350 miles.

Although Arnold did not suspect a thing, a little bit of sabotage might have been thrown in the mix. He had also been given maps drawn by Kennebec area surveyor Samuel Goodwin, but Goodwin was known to have loyalist sympathies. As events unfolded, the Goodwin maps were to prove riddled with inaccuracies and largely worthless. Was this deliberate sabotage? It is hard to say after the passage of more than 200 years. The Maine wilderness was covered with thick and seemingly endless stands of birch and pine, and not all areas had been explored by the white man.

Based on these flawed projections, Arnold figured it would take the Quebec expedition about 20 days to reach their goal. Though he did not know what was to come, Arnold did hedge his bets enough to allow for 45 days of rations for the men. He also was well aware that it was August, and that the summer was quickly slipping away. In those northern climes, winter often arrived early, defying any estimates based solely on the calendar.

Washington had his hands full at the time, because when he arrived at Cambridge, he was appalled at what he found. The Continental army, which had been founded on June 14, was not a real army of trained soldiers but an unorganized, often slovenly, ill-disciplined mob. The commander-in-chief had to do everything, including tasks normally relegated to junior officers. Even sanitation was beyond many of these men, and the general had to make sure proper latrines were dug.

He also was faced with the task of making the men under his command accept that they were Americans united under a common cause. Colonists considered themselves as New Yorkers, Georgians, or Virginians first, and regional rivalries sometimes erupted into serious altercations. Yet these men had the potential to be good soldiers, and most of them were eager to strike a blow against the British.

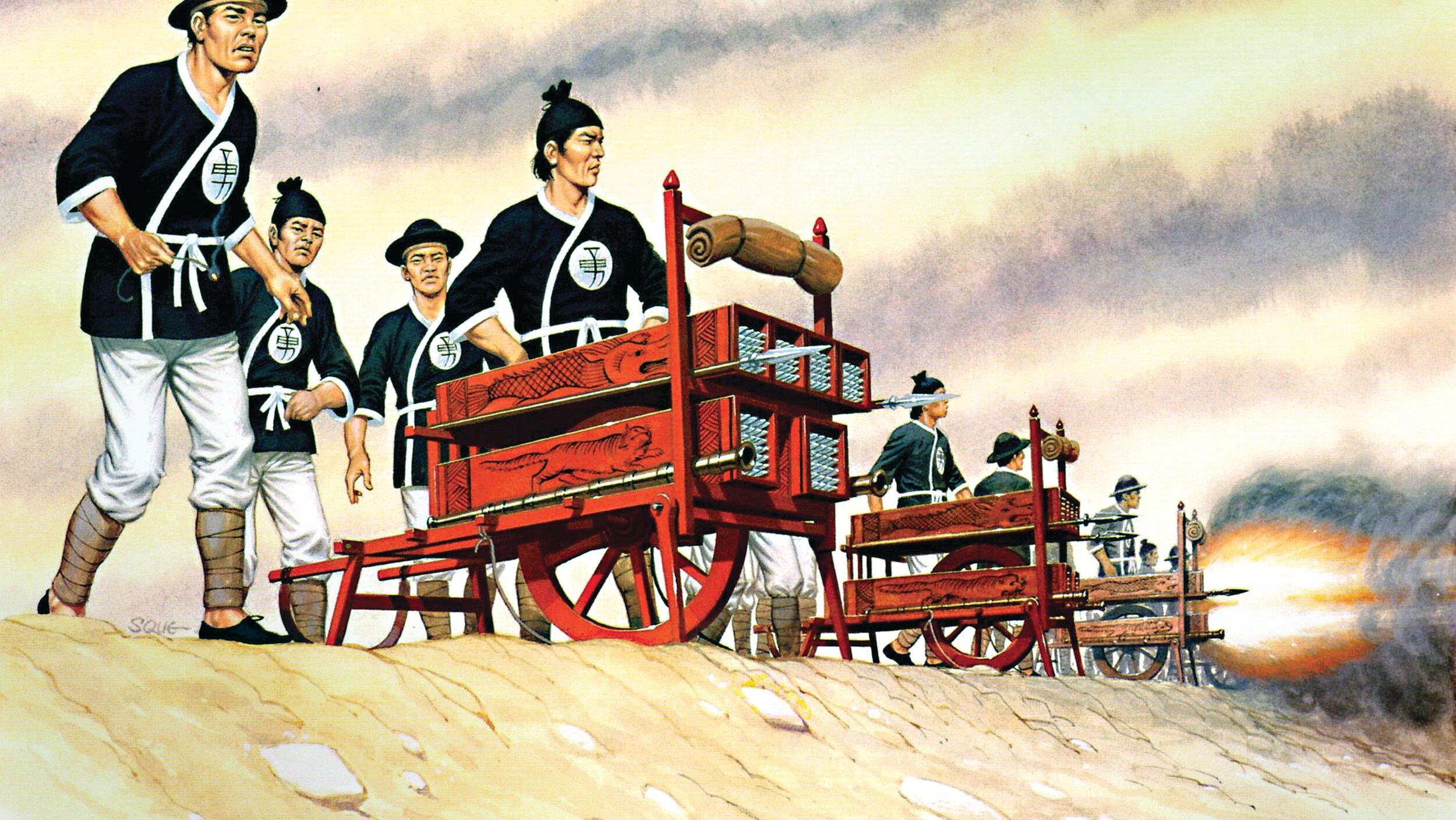

The next step in forming a Quebec expedition was to call for volunteers for the mission. Washington decided 676 privates would suffice, along with their officers. But 275 riflemen organized into three companies also would also be attached to the effort. Most Americans were armed with smoothbore muskets that had an effective range of 100 yards at best, and usually a lot less. In contrast, the rifle, which had grooves in the barrel that put a spin on the bullet and created greater accuracy, when put in the hands of a trained marksman could reach 300 yards.

Washington stipulated that any volunteers must be “woodsmen, and well acquainted with bateaux [flat-bottomed boats]; so it is recommended that none but such will offer themselves for this service.” The general was well acquainted with the hazards of wilderness travel. In 1753, when he was just 21 years old, Washington had trekked through the Ohio country woods in the depth of winter.

But Washington’s sage advice was largely ignored. There simply were not enough genuine woodsmen to fill the ranks. The volunteers that came forward were mostly farmers, tough and hearty enough, but entirely ignorant of the skills needed for wilderness survival.

The expedition began to coalesce under Arnold’s watchful eye. Most of the men were going to be in two battalions, one commanded by Lt. Col. Roger Enos and the other by Lt. Col. Christopher Greene. Greene was a cousin of Brig. Gen. Nathanael Greene, who would later prove himself as one of Washington’s best subordinate generals.

Yet there also was a third battalion, which had three companies of riflemen at its core. The riflemen were led by Captain Daniel Morgan, a man who was something of a legend. Affectionately nicknamed the “Old Wagoner,” Morgan had driven supply wagons for the British Army during the French and Indian War. When a British officer hit him for some alleged offense, Morgan punched the redcoat with such force he knocked him down. Striking an officer was a cardinal offense in the British army, and Morgan was sentenced to 500 lashes. Usually this was a death sentence, but incredibly, Morgan survived the ordeal.

Washington facilitated the construction of the bateaux on September 3 with boat builder Reuben Colburn of Gardinerston, Maine, who was in Cambridge at the time on another matter, and instructed Arnold to correspond with him regarding any specifications he might have in mind. Meanwhile, a furor erupted when some of the soldiers demanded a month’s pay in advance; when the money was forthcoming, things settled down.

The designated point of departure for the expedition was Newburyport, Massachusetts. Morgan’s riflemen led the way, leaving Cambridge on September 11, with the last companies departing two days later. Sea travel was uncommon for the average American at the time, and many of these farm boys must have looked at this short voyage with some trepidation.

Some of the men were disappointed by the 11 vessels that waited them in Newburyport harbor. They were little better than “dirty coasters and fish boats,” said one man. Yet they were seaworthy. In some respects, Arnold experienced his greatest anxiety during the passage of the ships from Newburyport to Maine. The British ruled coastal American waters, and one never knew if a British frigate might make a sudden and unwelcome appearance. Once spotted, the little American fleet might be sunk or captured in short order.

But Arnold’s luck held, and the three-day voyage passed without incident. That is not to say the Arnold fleet emerged completely unscathed. The seas were rough—so stormy that many of the soldiers became seasick. “Such a sickness, making me feel so lifeless, so indifferent whether I lived or died!” said one man. Dr. Isaac Senter, one of the expedition’s physicians, laconically noted the storm-tossed vomiting as soldiers “disgorging themselves.”

Arnold arrived in Gardinerston, six miles south of Fort Western, on September 22 and inspected the bateaux. Two days later, he sent two reconnaissance parties to scout the route north. In the succeeding days, the rest of the expedition departed Fort Western. Morgan and his riflemen constituted the vanguard, followed on successive days by Greene with three companies and Major Return Jonathan Meigs with four companies. Arnold left the fort with two companies on September 29, followed by Enos with one company. The going was slow and difficult, with the stretched-out column taking two days to travel the first 18 miles.

Takonic Falls provided the first real inkling of the hardships to come, a portage of half a mile around the cascading, foaming waters. It was not just the boats that were the issue; the men had to transport some 65 tons of supplies past the falls, as well. But they also discovered that rowing was largely a thing of the past, because the steady succession of shoals, rapids and shallows made their paddles all but useless.

Many times, the men had to wade chest-deep in the frigid waters as they hauled the boats upstream by rope. It was a general method known by the French Canadians as cordelling. It was a dangerous proposition, given that most colonists did not know how to swim. The current was swift, and if a soldier slipped, there was a strong likelihood he would drown.

The boiling rapids of Five Miles Falls came next. What followed was a treacherous half-mile approach to Skowhegan Falls. Despite the hardship entailed in going upriver with the bateaux, the members of the expedition were still in good spirits, partly because their rations were augmented by the fish and game that were very abundant in this region. The mighty Kennebec was full of fish. “[I ate] broiled salmon for supper and slept comfortably about 13 hours,” wrote one member of the expedition in his diary.

There were still settlements in the area, though they became fewer and fewer as the journey progressed. These sturdy pioneers, living on the fringes of colonial civilization, were usually generous and ready to help, but also charged high prices for goods when they could. Most seemed to be on the side of the Patriots and endorsed the expedition’s goals wholeheartedly. There were a few pro-British loyalists in the region, but even they cooperated to a point. For the most part, they were not held in contempt by the Patriots. For example, local settler Ephraim Ballard was described as a rank Tory, but also an honest man.

It was not long before rain began to fall, but by that time the men had grown accustomed to being constantly wet from the arduous task of hauling the boats in the river. Temperatures plummeted, and the first frosts appeared in late September. The bateaux had been constructed rapidly and were shoddily built, and conditions made them deteriorate rapidly. Some sprang leaks, which spoiled the supplies being transported in the bateaux, and others were simply falling apart. To their credit, Colburn’s artificers did their best to plug holes and caulk leaky seams in the battered craft.

The growing litany of woes grew with every passing hour. “The bread casks not being water-proof, admitted the water in plenty, swelled the bread, burst the casks, as well as soured the whole bread,” recalled on soldier. “The same fate attended a number of fine casks of peas.” Most of the salted beef was also bad, and the first cases of dysentery and diarrhea began to appear among them.

By early October, the expedition had reached Norridgewock Falls, which was actually a series of rapids. Arnold managed to secure the services of oxen teams, which temporarily took the place of the exhausted men and dragged the boats and supplies the mile or so past the falls. The sure-footed beasts did their best, but oxen are incredibly slow, and the boggy soil and heavy rain did not help matters.

When the expedition left Norridgewock, they entered a rougher, more mountainous and desolate land. They were also bidding adieu to civilization; they were on their own now, with no one to help them. It was also dawning on Arnold that his maps charts and other data were seriously flawed. The expedition was running out of food, partly due to spoilage and partly due to Arnold’s miscalculation of the travel distance.

At last, the various divisions of the long-suffering army arrived at the beginning of the Great Carrying Place, a 12-mile portage that is essentially a land bridge connecting the Kennebec River and the Dead River, which is the western branch of the Kennebec. The Great Carrying Place is important, because by using it travelers avoided the Kennebec’s most dangerous stretch of boiling rapids.

The Great Carrying Place had challenges of its own. For most of the route, the soldiers travelled on three lakes, with long stretches of land in between. The trail had eight miles of land portage, as well as four miles of rowing across the three ponds. The soldiers’ shoulders were rubbed raw from carrying their bateaux. The damp soil made the task all the more difficult. Weighed down by carrying their heavy bateaux, soldiers found that their legs sunk deep into the muck. The process of walking through the vicious muck drained their last reserves of energy.

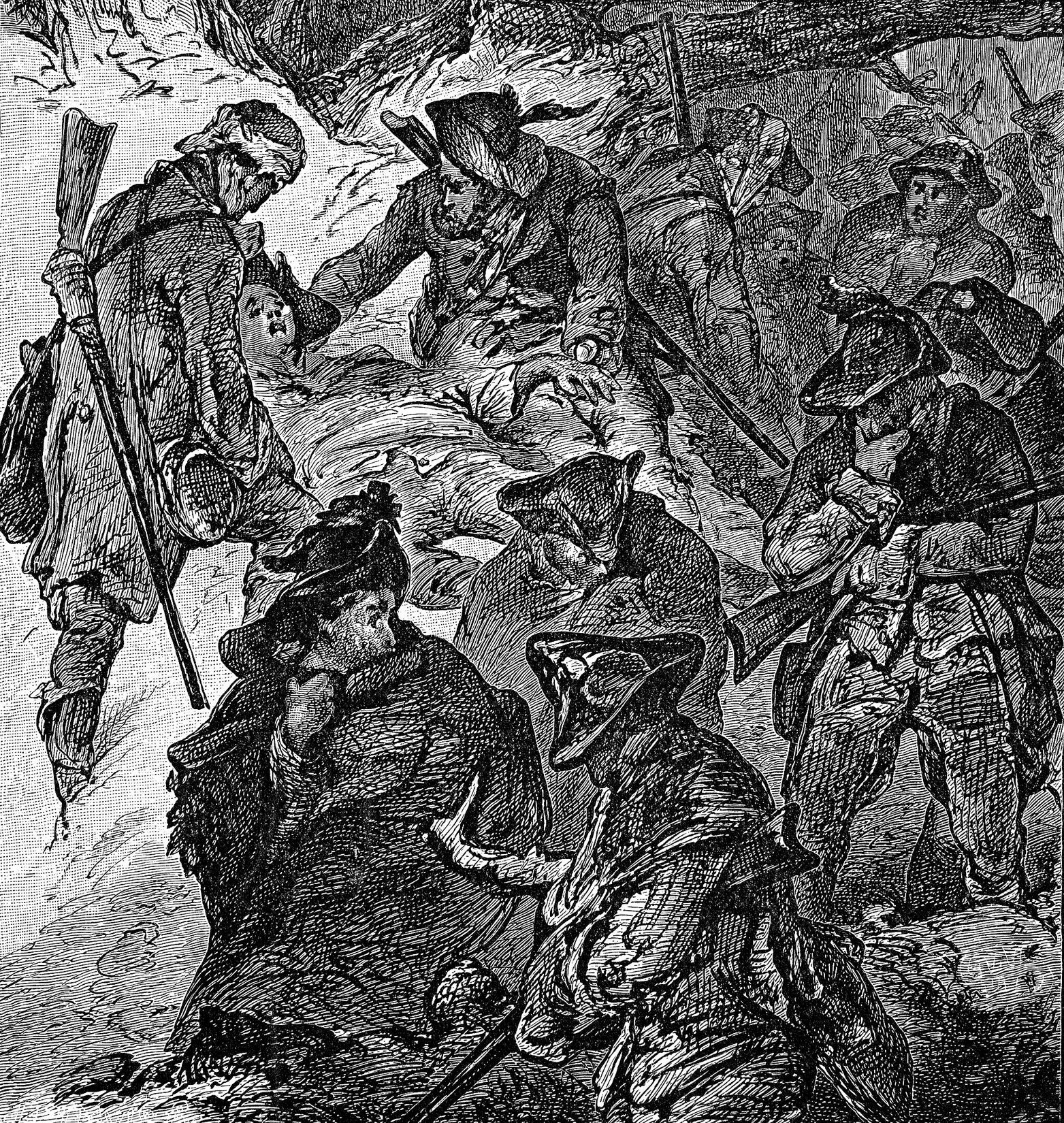

When they reached a pond, the men’s raw shoulders and aching muscles received little rest, for they then had to row their heavy bateaux. If that were not bad enough, the men had to retrace their steps time and again as they shuttled supplies forward between lakes. Rations were scanty at best, and occasionally the men were able to bag a wild animal. At one point, a party of soldiers succeeded in killing a 200-pound moose, which was scrawny by moose standards given that an adult male moose can weigh 1,400 pounds, but even so the meat afforded the men some much-needed protein. Such feasts were few and far between, though.

The two battalions finally reached the Dead River on October 13, but their trials were only just beginning. Progress was slow but steady, even though the men were lashed by an incessant, drenching rain. Eight days later, the rain fell even harder and was accompanied by howling winds of unusual strength. To the weary soldiers, it seemed as if the floodgates of heaven had been torn asunder.

The troops cast about for higher ground to camp for the night, but their efforts were in vain. They found that the river had caught up with them. The deluge had been so great that the river had risen eight feet in as many hours. Even worse, the river had widened from 20 yards to 200 yards. The riverbanks were now obliterated, making navigation difficult if not impossible. It was said that flood waters reached a mile in width in some places. The increased volume had brought to life the Dead River with currents so swift they swamped and sank six bateaux.

The sinking of those bateaux must have seemed a particularly cruel development because the food and provisions stored in the bateaux were lost. At that point, Arnold had some serious doubts about the expedition, even though he wanted to continue. But he decided to seek the counsel of his officers on the matter. He told them he wanted to continue, and to his surprise they agreed with him.

There was one glimmer of hope at that point, which was that they were relatively close to the Chaudière River, an area known to have French Canadian settlements. Arnold intended to send an advance party ahead to try to make contact with these people in the hope of obtaining badly needed food and other provisions that could be brought back to the main column. In addition, it was decided that the sick and infirm would be sent back to the American settlements on the upper Kennebec.

But not all of the troops supported Arnold’s decision to press on to Quebec. Some elements of the expedition were further behind, and these men were in a very bad way. Lt. Col. Enos held his own council of war, and after much wrangling it was decided that he would take 300 men and return home. Lt. Col. Greene would take the remainder and continue forward in the hope of reuniting with Arnold further up the trail.

The threat of starvation loomed over the entire enterprise at that point. For the most part, they had only flour to mix with water for sustenance. Starving soldiers dined on such diverse items as shaving soap, pomatum, lip salve, shoe leather, and even cartridge boxes. Perhaps it was inevitable that one officer’s dog, which had somehow survived the ordeal to that point, wound up as a welcome addition to the communal cooking pot.

The unfortunate canine was a Newfoundland, a large breed known for its massive paws. He was owned by Captain Henry Dearborn. The men “ate every part of him, not excepting the entrails, and after finishing their meal they collected the bones and carried them to be pounded up, and to make broth for another meal,” wrote Dearborn. The soldiers killed two other dogs, too. One time, the soldiers boiled a potpourri that included broth made of dog’s head, a squirrel’s head, and candlewicks.

The food crisis eased somewhat when the advance party sent forward by Arnold reached some of the French-Canadian settlements. The locals proved friendly, sympathetic, and generous, sending a large amount of food back to the main column. On November 9, the advance party of Americans arrived at the St. Lawrence River opposite Quebec City.

But the expedition was still strung out along the trail, and it was going to take some time for it to assemble on the south bank of the St. Lawrence. This did not stop Arnold from contemplating the assault on Quebec. He organized work parties that felled trees and began crafting ladders with which to scale Quebec’s high stone walls.

While the troops in the main column continued to slog their way through the inhospitable wilderness, Carlton was preparing Quebec for the inevitable American onslaught. No one knew the exact timing of the invasion, but everyone knew it was coming, from Carlton to the poorest Quebecois farmer. Arnold’s earlier raid at Saint-Jean may have been a masterstroke, but it had also alerted the British the Americans had possible designs on Canada. After all, they’d managed to get within 20 miles of Montreal with near impunity, exposing both the weaknesses of the British defenses and the dangers of complacency.

The raid had sent shock waves throughout Quebec province, and Carlton was particularly concerned. A year earlier he had sent two regiments of redcoats to reinforce General Thomas Gage in his troubled occupation of Boston. Carleton now realized he would be desperately short of professional soldiers. Winter would soon be upon them, and the St. Lawrence River, their main pipeline of men and supplies from England, would soon be clogged with ice. That meant that Carlton could not expect help from the mother country until the following spring.

When the Americans first appeared on the banks of the St. Lawrence, Carlton was absent. The general was in Montreal, because he knew Canada’s second major town was also threatened with American occupation. For the moment, the defense of the walled city would be in the hands of the Lieutenant Governor Hector Theophilus Cramahé. The lieutenant governor did not have much to work with: just some French Canadian and British resident militiamen. The French were of dubious loyalty, and Cramahé was not even sure the British residents would fight.

Arnold could pause for a brief moment to take stock of his achievement leading his troops through the Maine wilderness. Eleven hundred men had left Cambridge almost two months earlier, and he had with him 675 troops on the south bank of the St. Lawrence. Three hundred had retreated with Enos, and to that number could be added 70 men whom Arnold had evacuated because they were too sick to go on. The remainder were either dead or had likely deserted.

The difficult trek had taken 45 days, not the estimated 20, and covered 350 miles, not 180 miles. Because of the generosity of the French Canadians, his troops now had enough to eat. By the end of their trek many of the men were shoeless, or had shoes so worn and ridden with holes they scarcely covered their blistered feet. Proving that necessity is indeed the mother of invention, the men used raw beef hides from freshly slaughtered cattle and fashioned crude moccasins from them.

Their clothes were in tatters, too. They were “torn to pieces by the bushes and hung in strings,” recalled one soldier. “Few of us had any shoes, but moccasins made of raw strings. Many of us [were] without hats, and our beards long and visages thin and meager.” They had little or no powder and lacked artillery. They still might have triumphed, if only they had arrived a few days earlier.

Time is often the deciding element in warfare, and the Quebec campaign provides ample proof of the notion. The American vanguard arrived at the St. Lawrence River opposite Quebec City on November 9. But Arnold chose to wait for stragglers to catch up to the main army. He also decided to try to gather enough local boats to cross the swift-flowing St. Lawrence River, which was a mile wide at Quebec City. Arnold lost no time in contacting Indians to obtain their birch bark canoes. Local Quebecois also agreed to build some new ones.

Some things were beyond Arnold’s control. The weather turned bad, with three consecutive days of snow squalls. What is more, he wanted to wait to cross on a moonless night to avoid detection by British boat patrols. These delays in crossing tipped the odds substantially in favor of the British.

Arnold crossed successfully, but he was outnumbered two to one. The notion of undertaking an attack on a walled city without artillery posed its own daunting challenges. He had to wait for reinforcements and basically bluff the British into thinking he had far more men than he actually had. On the whole, his bluff seems to have worked, though the British rejected his call to surrender out of hand.

However, the other parts of the invasion of Canada seemed to be proceeding without a hitch. The second wing of the invasion advanced successfully up Lake Champlain, and all was going according to plan. Schuyler had fallen ill, and therefore command of the second prong of the invasion fell to Maj. Gen. Richard Montgomery. The Montgomery expedition seemed to have a relatively easy passage north, and it took Montreal with little difficulty. Governor Carlton narrowly escaped capture.

In a move that was to determine the course of the campaign, Carlton sent Colonel Alan MacLean downriver with 60 redcoat regulars and 120 men of his own Highland Emigrant Regiment. The Highland Emigrants were Scotsmen mainly from Canada but also hailing from as far away as the Carolinas. They were good soldiers and formed a backbone that would be a vital element to the overall defense of Quebec City.

McLean became the de facto leader of Quebec, and a very relieved Cramahé retreated into obscurity for the rest of the campaign. Colonel McLean wasted no time in organizing a proper defense. There were two British warships anchored at Quebec, HMS Lizard and HMS Hunter, and their crews were pressed into service as a marine division. Carlton himself arrived in Quebec on November 19 and took over command from McLean but found his subordinate had done a commendable job.

Besides the Royal Emigrants, some fusilier regulars, and the Royal Navy seamen, there were British and French-Canadian militia. The Quebecois were still unreliable, but Carlton had no choice but include them in the ranks. To bolster confidence and put up a brave show, the governor occasionally ordered an artillery bombardment.

In the meantime, Arnold could do nothing until Montgomery arrived from Montreal with supplies, clothes, and above all reinforcements for a possible assault on the Quebec’s very formidable battlements. When Montgomery appeared, Arnold’s long-suffering command felt victory was in their grasp. The attack would be at two separate parts of the city. Arnold would attack the defenses at the north end of the city, while Montgomery would storm the barricades on the south end of the lower town. The date chosen for the attempt was December 31, 1775.

The Americans hoped to cloak their advance by attacking at night and in the midst of a raging blizzard. Buffeted by the frigid gale, Montgomery’s men clambered over great clunks of river ice to creep close to their goal, a wooden palisade that fronted a two-story blockhouse.

Montgomery, who was leading from the front, supervised his men as they sawed a gap though the wooden palisade stakes. They succeeded in opening a gap in the barricade, and their work apparently was undetected, since the soldiers in the blockhouse up ahead were silent. Montgomery led a small party of soldiers through the gap. The blockhouse loomed before them amidst wind-whipped snow flurries.

Suddenly, three of the blockhouse’s gun ports came to life with a deafening roar, each aperture erupting with gouts of smoke and flame. Montgomery and his party were just 40 feet away when the cannon fired, instantly killing the general and many others. Montgomery’s men, their commander dead and under heavy fire, beat a hasty retreat.

Arnold was not having much better luck. He bravely led his men toward a log palisade, but as he was going over the wall, he felt his leg go numb. The lead ball had missed his boot top, but ricocheted from his shin to his inner leg, finally lodging in his Achilles’ tendon. Bleeding and unable to walk, Arnold was dragged to the rear to see a surgeon. Captain Morgan took command, and he managed to get a foothold in the lower town.

The fighting raged for another three hours, with Morgan and his men often fighting house-to-house. But in the end the effort, while heroic, was doomed to failure. The British got the upper hand, and Morgan and 426 Americans were forced to surrender. The American suffered about 84 killed and wounded compared to British losses of five dead and 14 wounded.

With the aid of reinforcements, Arnold managed to keep up a partial siege for another few months. “I have no thoughts of leaving this proud town until I first enter it in triumph,” wrote Arnold. But when the ice melted on the St. Lawrence that spring, a British fleet appeared, carrying 10,000 reinforcements. The Americans had no choice but to raise the siege and retreat south.

Benedict Arnold’s attempt to take Quebec and Canada came within an ace of succeeding. Bad timing, bad weather, bad maps, and bad luck all played a part in its failure. Arnold would go on to win glory at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, and afterwards everlasting infamy three years later as a traitor to the American cause.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments