By Al Hemingway

Many who remember the 1968 Tet Offensive in South Vietnam still believe that the U.S. military suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the North Vietnamese Army. In America’s first television war, people watched as the media reported communist insurgents seizing the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, defeating the Marines at Khe Sanh, and overrunning nearly every major village in the country. Although there is an element of truth to all the above, the larger truth is that American forces handily defeated Ho Chi Minh’s army. In fact, the South Vietnamese communist cadre, the Viet Cong, sustained horrific losses from which they did not recover for the remainder of the war.

Why then, if the United States and her South Vietnamese allies smashed the insurrection on the battlefield, was the Tet Offensive portrayed as a humiliating defeat? In his new book, This Time We Win: Revisiting the Tet Offensive (Encounter Books, New York, 2010, 364 pp., index, notes, photos, $25.95, hardcover), author James S. Robbins gives us some of the reasons why this happened—and why it is still continuing today.

Although the enemy wanted to send a message to get the Americans to the bargaining table, Robbins says, it was also a frantic attempt by Hanoi to attack the cities and major hamlets in the country and have the South Vietnamese rise up and overthrow the Saigon government the communists viewed as a bunch of “American puppets.” However, despite the extreme severity of the attacks, the South Vietnamese did not join the enemy’s ranks. Although battles such as Khe Sanh and Hue City lasted for some time, the majority of the uprising was quickly squashed.

The media played a major role in reporting to the American public that the Tet Offensive was a serious defeat, the author maintains. “The Tet story line is always lurking when U.S. forces are engaged against weak, unconventional enemies that lash out under limited and exceptional circumstances and briefly capture the attention of the media,” writes Robbins. “Tet is then fought in these new guises, amplified in the media-political echo chamber.”

The media played a major role in reporting to the American public that the Tet Offensive was a serious defeat, the author maintains. “The Tet story line is always lurking when U.S. forces are engaged against weak, unconventional enemies that lash out under limited and exceptional circumstances and briefly capture the attention of the media,” writes Robbins. “Tet is then fought in these new guises, amplified in the media-political echo chamber.”

Then-President Lyndon Baines Johnson, who with the help of the “best and the brightest,” formulated America’s flawed strategy during the war, was so shaken by Tet that he did not seek the Democratic Party’s nod for reelection. Johnson, the consummate politician, could have used his Washington insider skills to diffuse the situation and vigorously pursue the enemy, who were literally on the ropes, says Robbins. Disillusioned and paralyzed by the turn of events, Johnson instead continued the strategy of limited war that had gotten him and his administration into the quagmire from the outset.

The events that followed the Tet Offensive doomed any chance for an American victory in Southeast Asia. After the Watergate scandal, resurgent Democrats passed the Foreign Assistance Act in 1974 that severed military aid to South Vietnam. The Paris peace talks deadlocked, and the communists watched with delight as America’s political will dissolved. Emboldened, they began their master plan to seize the country, which finally succeeded in April 1975.

Today, with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the legacy of the Tet Offensive of 1968 is still fresh in politicians’ minds—for all the wrong reasons. The debate of whether or not we should have become involved in these countries is now a moot point. American leaders must stand firm and craft a successful policy of containment and disengagement, or else the country might endure another Tet Offensive and the humiliation of watching American personnel being airlifted off rooftops.

Give Me Tomorrow: The Korean War’s Greatest Untold Story—The Epic Stand of the Marines of George Company by Patrick O’Donnell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010, 261 pp., index, notes, photos, $26, hardcover.

Give Me Tomorrow: The Korean War’s Greatest Untold Story—The Epic Stand of the Marines of George Company by Patrick O’Donnell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010, 261 pp., index, notes, photos, $26, hardcover.

It is always a pleasure to see another book published on the Korean War, especially one depicting heroic achievements that have long been forgotten. Such is the case of George Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division, which fought off hordes of Chinese during the rout of the Eighth Army at the Chosin Reservoir in November and December 1950. Led by the indomitable General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, the leathernecks endured a harrowing march, constantly engaging the enemy, until they reached the safety of the coastal city of Hungnam.

Author O’Donnell’s book is not just about the epic struggle; it is also a testament to the bravery and fortitude of the American fighting man. George Company, like many others, was filled with numerous green recruits who had never seen combat. With a sprinkling of battle-hardened veterans of World War II, the unit gelled into one of the premier frontline companies in the division. Men from all walks of life, with absolutely nothing in common, were thrown together in one of the most famous campaigns in Marine Corps history. In all, 149 paid the supreme sacrifice during the war,

O’Donnell has followed the survivors of George Company after they left the Marines at war’s end. He attended their reunions and was able to gather their personal observations and experiences at Chosin. O’Donnell used a similar format in his previous bestseller, We Were One, about the Marines of 3/1 who fought house-to-house in Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004.

Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign by Peter Hammond, Pen & Sword Military, South Yorkshire, UK, 2010, 166 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $32, hardcover.

Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign by Peter Hammond, Pen & Sword Military, South Yorkshire, UK, 2010, 166 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $32, hardcover.

For 30 years, England fought a bloody civil war to decide who would rule the island kingdom. The conflict is referred to as the War of the Roses because of the badges worn by the opposing sides, the White Rose of York and the Red Rose of Lancaster, the two rival branches of the House of Plantagenet.

The author, a medieval historian, traces the origins of the final campaign of the 30-year war, the Battle of Bosworth Field. King Richard III of the House of York, who had gained the throne from Edward V in 1483, met his Lancastrian opponent Henry Tudor at Redemore Field, near Bosworth, in August 1485. To this day, the location of the actual battlefield is still under question.

In the end, Richard was slain in the fighting. There are varying accounts of how he met his death, one holding that he tried to flee but was surrounded and slain after his horse bogged down in a nearby marsh. However, most say that Richard fought valiantly beside his troops, urging them onward and giving them support and encouragement. “However Richard met his end,” writes Hammond, “he was the only English king to die in battle.”

Although sporadic fighting continued, the campaign at Bosworth marked the end of the civil war that had lasted for three decades. The author not only describes the battle in great detail, he gives the reader a glimpse into the reign of Richard III, who, although only holding the crown for two years, has remained prominent—if not always praised—in English literature to this day. Indeed, one might argue that Richard’s greatest defeat came at the hands of one William Shakespeare, 100 years after the king’s death.

Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg, the Campaigns That Changed the Civil War by Edwin C. Bearss with J. Parker Hills, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., 2010, 400 pgs., notes, maps, $28, hardcover.

Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg, the Campaigns That Changed the Civil War by Edwin C. Bearss with J. Parker Hills, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., 2010, 400 pgs., notes, maps, $28, hardcover.

Much has been written about the pivotal battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg in the Civil War. However, when noted historian Ed Bearss writes a book on the subject, one must take notice. A wounded U.S. Marine veteran of World War II, Bearss in his own unique style has written an exceptional account of two of the conflict’s battles that had a major impact on historical events.

As 1863 was dawning, the North was in a terrible way. With few exceptions, the Confederacy had whipped the Union forces on the battlefield. The northern newspapers were calling for peace talks to end the war and let the South go its own way. However, thanks to events in the western theater of operation and at a sleepy farming community in southern Pennsylvania, all that would change.

In late June 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee commenced his second invasion of the North (the first was turned back at Antietam nine months earlier) and crossed over into Pennsylvania. At the village of Gettysburg, Union and Confederate forces clashed in a bloody three-day struggle that saw Lee’s army vacate the battlefield on July 3. In Mississippi, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had laid siege to the city of Vicksburg, the last major stumbling block to controlling the Mississippi River. Ironically, the following day, Vicksburg surrendered. “The Vicksburg Campaign didn’t cause Gettysburg, but Gettysburg was Lee’s and the Confederate government’s response to the Vicksburg dilemma,” writes Bearss. “It was a response that failed.”

Custer: Lessons in Leadership by Duane Schultz, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010, 206 pp., index, photos, $23, hardcover.

Custer: Lessons in Leadership by Duane Schultz, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010, 206 pp., index, photos, $23, hardcover.

He was called the “boy general with the golden locks” by one admiring newspaper. His exploits were no less than amazing during the Civil War, but George Armstrong Custer’s shining star soon became tarnished at war’s end when the battlefield shifted from the East to the endless expanses of the American West, fighting a foe that had considerable expertise in guerrilla warfare.

Although he had finished last in his class at West Point, Custer, through influence and political connections, made the rank of brigadier general at the tender age of 23. His bravery and daring while a cavalry officer in the Union Army are the stuff of legends. Bravery aside, Custer was a reckless man who never got over his little boy instincts throughout his adult life. He would end his letters to his wife Libby, “Your little boy, Autie.” It was this rash behavior that would finally prove to be his demise at the Battle of the Little Big Horn when Custer and 225 of his troopers were slain by Sioux and Cheyenne warriors in Montana on June 25, 1876.

The author examines Custer’s actions in both conflicts, as well as his leadership skills, his strategy and his interactions with his troops. While one can argue whether or not the boy general’s actions on that fateful day in June 1876 were valid, no one can dispute one fact—Custer was born to be a soldier. And he died as one.

Brute: The Life of Victor Krulak, U.S. Marine by Robert Coram, Little, Brown, New York, 2010, 384 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.99, hardcover.

Brute: The Life of Victor Krulak, U.S. Marine by Robert Coram, Little, Brown, New York, 2010, 384 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.99, hardcover.

Although small in stature, Lt. Gen. Victor H. “Brute” Krulak was a giant in the Marine Corps. He received his nickname while attending the United States Naval Academy and it remained with him throughout his career. Born in Denver, Colorado, to Jewish immigrants, Krulak’s early life is shrouded in mystery. He seems to have downplayed his Jewish faith, no doubt because of the rampant anti-Semitism of the period. His brief interval in Coronado, California, two different high school diplomas, and a short-lived marriage at the age of 16 still remain unexplained.

Despite his mysterious background, Krulak graduated from the Naval Academy in 1934. Again under mysterious conditions, he was granted a waiver because of his height and weight. When he pinned on the eagle, globe, and anchor, Krulak’s dream of becoming a Marine was realized. Throughout his illustrious career, Krulak seemed to be always in the forefront. Krulak undertook secret missions to China, served as a paratrooper in World War II, and was a staunch advocate of the helicopter in the Korean Conflict and of counterinsurgency in Vietnam.

However, it would be a battle in the halls of Congress that would probably be Krulak’s greatest contribution to his beloved Corps. After World War II, many high-ranking Army officers and politicians, including President Harry S. Truman, wanted to drastically reduce the role of the Marine Corps. Krulak and other Marine officers formed a loose-knit group called the Chowder Society and eventually, through political connections, were able to prevent such a reduction from happening.

Coram’s book is an intriguing account of a charismatic individual who, although he hides much of his personal life, is still a hero. As the author writes, “He was a hard man, who could make hard decisions.”

War Party in Blue: Pawnee Scouts in the U.S. Army by Mark Van De Logt, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2010, 350 pp., notes, index, photos, $34.95, hardcover.

War Party in Blue: Pawnee Scouts in the U.S. Army by Mark Van De Logt, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2010, 350 pp., notes, index, photos, $34.95, hardcover.

Although the Pawnee Battalion, as it was unofficially called, contributed much to the success of the U.S. Army’s efforts to subdue Native Americans after the Civil War, very little is really known about this unique band. Their role in the Plains Indian Wars was much more than the standard scouting and tracking, although they excelled in both areas. They were in the forefront of major cavalry campaigns against their longstanding enemies the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Comanche.

For years, the belief was that cavalry officers taught the Plains Indians how to fight. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Pawnees, called “Wolf Men” by their adversaries, were already extremely adept at combat. It was often a bloody affair, and one that the Pawnee scouts fought on their own terms.

With the assistance of the modern Pawnee community, the author poured over numerous accounts and traveled to the various battle sites with descendants of the original Pawnee scouts. He has written a fascinating book about a mobile strike force that fought bravely and provided immeasurable assistance to the U.S. Army against Native American opponents in the West.

Double Death: The True Story of Pryce Lewis, The Civil War’s Most Daring Spy by Gavin Mortimer, Walker & Company, New York, 2010, 304 pp., notes, photos, $26, hardcover.

Double Death: The True Story of Pryce Lewis, The Civil War’s Most Daring Spy by Gavin Mortimer, Walker & Company, New York, 2010, 304 pp., notes, photos, $26, hardcover.

Spying was still in its infancy at the outbreak of the Civil War. Both sides relied upon not only military spies, but also a motley collection of daring and resourceful civilians. One such individual was Pryce Lewis, a Welshman who immigrated to America in 1856 and was employed by private detective Allan Pinkerton when Pinkerton volunteered his services to President Abraham Lincoln.

Lewis first posed as an English lord traveling through West Virginia to assess the situation and report back his findings to Washington. His detailed findings led to one of the Union’s earliest victories in the conflict. Lewis was eventually captured in Richmond by Confederate authorities, but escaped hanging because he was a British citizen. Another noted Union spy, Timothy Webster, was not so lucky. Betrayed by Lewis’s traveling partner, Webster was hanged.

Throughout the years, many believed that it was Lewis who had informed on Webster. And because he was a British citizen, Lewis’s attempts to gain a pension from the federal government were repeatedly denied. On a cold December day in 1911, a distraught Lewis climbed to the top of the Pulitzer Building in New York City and plunged to his death.

Gavin Mortimer has penned a wonderful, absorbing narrative o the life of Lewis. He also examines the early role of the Pinkerton Agency and the impact Great Britain had on the American conflict. It is an absorbing account for Civil War enthusiasts.

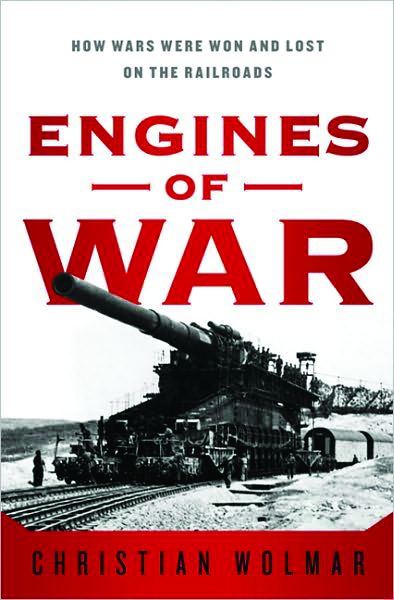

Engines of War: How Wars Were Won and Lost on the Railways by Christian Wolmar, Public Affairs, New York, 2010, 336 pp., notes, $28.95, hardcover.

Engines of War: How Wars Were Won and Lost on the Railways by Christian Wolmar, Public Affairs, New York, 2010, 336 pp., notes, $28.95, hardcover.

During the initial phase of the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, Union forces under Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell had the Confederates outnumbered. As the Union Army pressured the southerners, Brig. Gen. Joseph Johnston ordered a retreat. However, when additional reinforcements arrived, the southern troops counterattacked, driving Federal forces from the battlefield in a panic.

Although this happens many times in war, it was the method in which Johnston’s men arrived that turned the tide of battle—for the first time in American warfare it was via railroad. The author delves into the railroads and their huge impact during the conflict. With the help of railroads, armies could transport both men and matériel much more quickly than ever before. For more than a century, the military and railroads were inseparable.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments