By Christopher Miskimon

John “Chick” Donohue stood in the chaos of the American embassy in Saigon in early 1968 as the Tet Offensive raged around it. He needed a ride to a hotel near the Presidential Palace and asked two men who seemed on their way out. “That’s exactly where we’re going,” they told him. “Jump in.” Donohue got into the back of jeep, where one of the men handed him a gun belt with a .45 automatic. He strapped it on as the jeep tore through the streets, going straight past the street where Donohue’s hotel sat. As they neared the Presidential Palace, a rocket struck a jeep ahead of them. The vehicle and everyone in it flew into the air.

The two men in Donohue’s jeep jumped out and ran off with the jeep still rolling forward. Donohue jumped out, head down, and ran behind a palm tree. He watched a South Korean soldier grab a wounded man from the first jeep, dragging him to cover. (Donohue learned later the South Korean Ambassador’s house was nearby.) He looked around and found the Viet Cong position, a five-story building under construction, a mass of exposed concrete and steel rebar. Machine-gun fire and rockets poured from the skeletal structure.

Thirty yards away, a military policeman lay on the ground. Donohue felt he had to check on the man and began crawling to him. A hissing whisper startled Donohue. “Get back! Forget it. He’s dead. I checked him.” It was another man in plain clothes, wounded and lying in the street, clutching a .45. “I’m okay, stay back,” the man told him. Donohue looked around and could see inside the gates of the palace, where South Vietnamese policemen and soldiers seemed to be arguing with some Army officers. He got behind a wall and stayed there.

The ground trembled as several U.S. Army tanks rumbled along the street. American soldiers ran out to grab the wounded in the street. The American officers continued arguing with the South Vietnamese. The American wanted to blast the wall Donohue hid behind so they could go after the Viet Cong. The South Vietnamese wanted the Americans to leave; protecting the Palace was their job and they wanted to do it. The angry American officers told them if they did not want their help, they would find someone who did. With that, the tanks roared off down the street.

Next, an American police advisor appeared with a group of South Vietnamese police with him. Donohue listened as he tried to get the Vietnamese to go after the Viet Cong, but they were reluctant. In a Midwestern accent, the advisor told them he would lead them, so they agreed. As the advisor scrambled over a wall, an explosion blew him back over it. The Vietnamese grabbed his unconscious form, threw him into a pickup truck and raced away.

Next, an American police advisor appeared with a group of South Vietnamese police with him. Donohue listened as he tried to get the Vietnamese to go after the Viet Cong, but they were reluctant. In a Midwestern accent, the advisor told them he would lead them, so they agreed. As the advisor scrambled over a wall, an explosion blew him back over it. The Vietnamese grabbed his unconscious form, threw him into a pickup truck and raced away.

Donohue was now alone in the midst of a bloody, urban battle. He was a man with a mission, but he was not a soldier. Donohue was not affiliated with the CIA nor any military organization. However, he had served four years in the Marine Corps. At the time, he was a civilian and merchant marine who had disembarked from his ship with a mission to find his friends amidst the Vietnam War and give them messages of support from home and share a can of beer with them. Donohue’s gripping story is told in his own words in The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A Memoir of Friendship, Loyalty and War (John “Chick” Donohue and J.T. Molloy, William Morrow Publishers, New York NY, 2020, 256 pp., photographs, $34.99, hardcover).

One night in 1967, Donohue sat drinking with friends in a bar in New York City. All of them had lost friends in South Vietnam and were bothered by the antiwar protesters and the turmoil of their country. One of them came up with the idea of going to Vietnam, tracking down their friends, and giving them beer and support. It was a bizarre, albeit altruistic, idea, and only Donohue was crazy enough to do it.

Donohue tells his story in plain, straightforward prose. The tone alternates between laughter-inspiring events and melancholy-evoking ones. A number of photographs accompany the text, showing his dangerous adventure through a nation at war. Most Vietnam memoirs focus on Special Forces, infantrymen, or aircraft pilots. This is the tale of a civilian who should never have been there, but went anyway out of love for his friends.

The Russian Who Saved the World: A Novel of the Cuban Missile Crisis (Capt. Steven E. Maffeo, USN, Ret., Focsle LLC, Annapolis MD, 2020, 269 pp., photographs, $15.00, softcover)

The Russian Who Saved the World: A Novel of the Cuban Missile Crisis (Capt. Steven E. Maffeo, USN, Ret., Focsle LLC, Annapolis MD, 2020, 269 pp., photographs, $15.00, softcover)

In October 1962, the world was on the verge of World War III as the United States and the Soviet Union were at odds over the placement of Soviet missiles on the island of Cuba. U.S. warships blockaded the island to keep the Soviets from reinforcing its defenses. Near Cuba, cruising beneath the surface of the sea, was the Soviet Projekt 641-class submarine B-59. Its captain was overwhelmed by stress and fatigue as hostile ships roamed the surface hunting his vessel. He finally decided to launch a nuclear-armed torpedo at the aircraft carrier USS Randolph, an attack that would almost certainly start a full-scale nuclear war between the two nations. Only one man, a passenger aboard B-59, had a chance to avert the situation and prevent a global conflict.

This thrilling new novel is a fictionalized account of perhaps the most critical moment of the 20th century. The author is a retired naval intelligence officer with prior non-fiction work to his credit. His expertise and in-depth research make this work authentic and suspenseful, revealing much about the Soviet submarine service of the Cold War. This book elevates the author into the ranks of a select few skilled in the genre of historical naval fiction.

The Warriors of Anbar: The Marines who Crushed Al-Qaeda—The Greatest Untold Story of the Iraq War (Ed Darack, Da Capo Press, New York NY, 2019, 246 pp., maps, photographs, index, $28.00, hardcover)

The Warriors of Anbar: The Marines who Crushed Al-Qaeda—The Greatest Untold Story of the Iraq War (Ed Darack, Da Capo Press, New York NY, 2019, 246 pp., maps, photographs, index, $28.00, hardcover)

Lance Corporal Mike Scholl sat in the turret of an up-armored Humvee, peering over the sights of his M240B machine gun. It was November 14, 2006. The vehicle was deployed 50 meters from the west bank of the Euphrates River in Haditha, Iraq. Scholl was part of a patrol moving through the town, alert for an attack by Al Qaeda fighters, who attacked the local Marines almost every day. He looked for signs of those fighters, for any telltale hint of an improvised explosive device or for the sound of a rocket-propelled grenade. Neither Scholl nor his fellow Marines could afford to let their guard down for even a moment.

As the young Marine scanned the area beyond the barrel of his weapon, a grenade flew out of an alley and exploded near two Marines on foot. As the two men checked each other for injuries, other Marines looked for the grenade-thrower, but found no one. The attacker had simply melted back into the city. And none of the Marines could see another enemy fighter about to use a six-volt battery to set off a hidden bomb nearby.

The Marines sent to Anbar Province, Iraq, fought with perseverance and courage against an elusive and deadly foe. This new book tells the story of 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, as they struggled to restore peace to one of the country’s most violent regions. It is a well-written, descriptive, and highly readable work revealing what American troops in Iraq experienced.

The Cornfield: Antietam’s Turning Point (David A. Welker, Casemate Publishers, Havertown PA, 2020, 384 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

The Cornfield: Antietam’s Turning Point (David A. Welker, Casemate Publishers, Havertown PA, 2020, 384 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

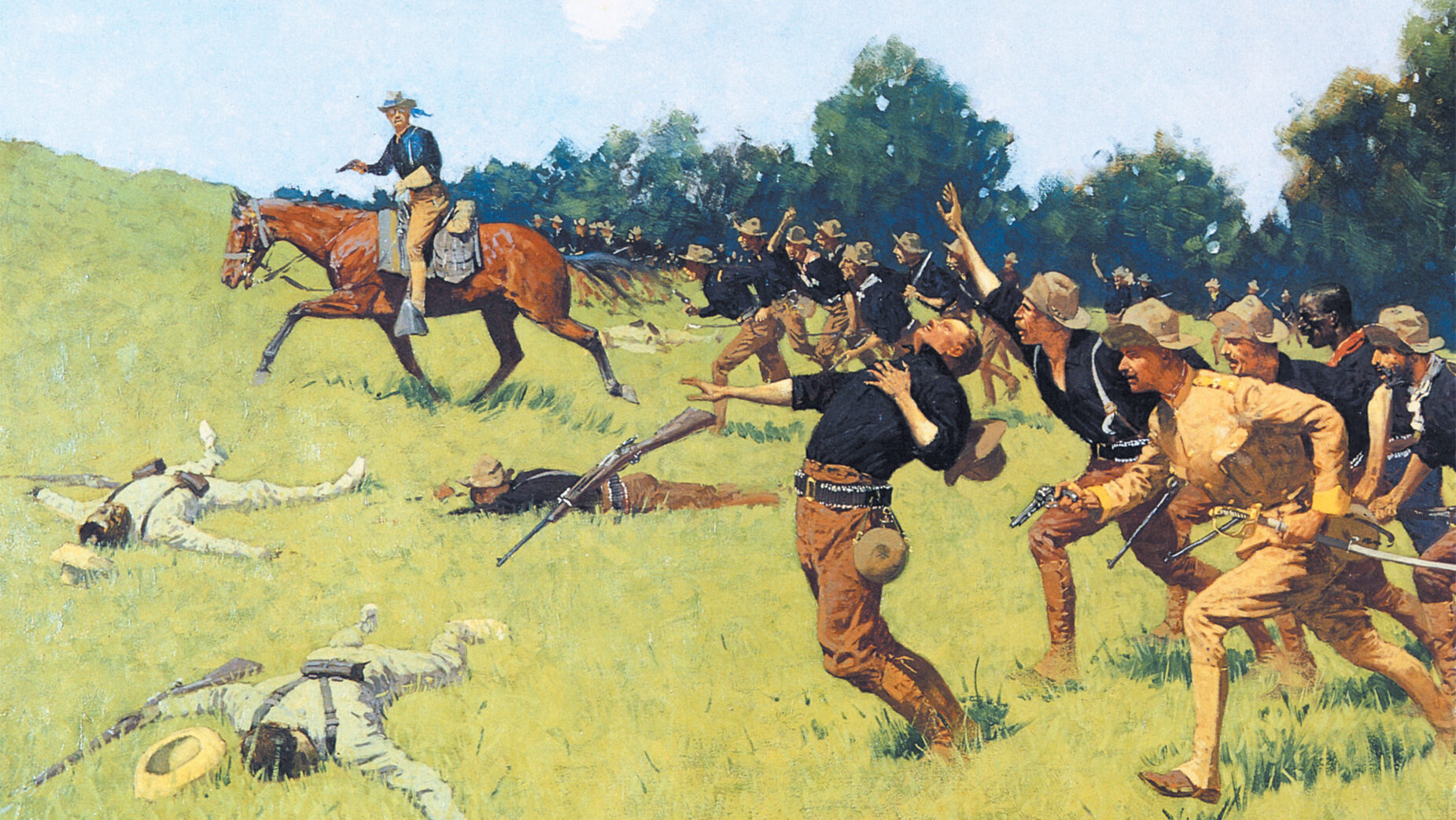

The morning phase of the epic clash at Sharpsburg turned on control of an area forever known as the Cornfield. The 30-acre Cornfield changed hands repeatedly as both sides attacked and counterattacked. Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan demanded that the position on the Confederate left flank be taken. The Union I and XII corps, as well as a division of the Union II Corps, were wrecked trying to obtain the objective. Approximately 5,000 Confederates faced 8,700 Federals in the Cornfield-Dunker Church sector. Of the 13,700 men engaged, 4,368 became casualties.

The author of this new work argues McClellan’s faulty tactics led to the bloodbath in the Cornfield. The morning action is described through a combination of gripping personal accounts, many of which are published for the first time. The work is a tantalizing narrative that sheds new light on the famous battle that became known as the single bloodiest day in the American Civil War.

The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History (Alexander Mikaberidze, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, 2020, 960 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History (Alexander Mikaberidze, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, 2020, 960 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

The series of conflicts known as the Napoleonic Wars were, for all intents and purposes, a world war. They began with the revolution in France and continued until Napoleon Bonaparte was finally defeated in 1815. The Napoleonic Wars constituted empire-building on a global scale. While the fighting in Europe seemed the main event, the combatants also struggled in the Americas, Asia and Africa. Napoleon’s success forced disparate states to form various alliances to oppose him. It took years of military and political maneuvering to bring about his end. Like other world wars, the Napoleonic Wars had long-lasting effects across the globe. The wars resulted in the Louisiana Purchase in North America, beginning the rise of the United States to world-power status. The wars’ end also cemented the Pax Britannica that would last for the rest of the century.

A worldwide perspective makes this new book stand out from most histories of the Napoleonic period. The author argues that the wars affected subsequent events outside Europe more so than within it. He lays out the work in three parts: First, he shows how the French Revolution paved the way for the wars. Next, those conflicts are explored in a chronological, global perspective. Then, he chronicles the fall of the empire and the wars’ aftermath, along with its lasting influences on modern times. It is a work of expansive breadth and great depth.

Army of the Roman Emperors: Archaeology and History (Thomas Fischer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown PA, 2019, 464 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover)

Army of the Roman Emperors: Archaeology and History (Thomas Fischer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown PA, 2019, 464 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover)

The army of Imperial Rome was actually quite small by modern standards. Many estimates place its strength at no more than 500,000 troops. Nevertheless, this force carried out myriad tasks out of all proportion to their numbers. They not only fought external enemies and internal threats, but also performed taxation, customs and policing roles across the empire. When not engaged in these functions, they built roads, ships, and buildings. Roman soldiers also acted as marines. Roman fleets are rarely discussed today, but they formed an important part of the empire’s military power.

It is a difficult task to pull so much information about the Imperial Roman military into one volume, but the author has succeeded in this new work. He combines archeological findings with historical data to present the uniforms, weapons and equipment of Roman troops in great detail. The author pays great attention to the changes the army went through over the centuries, showing how it evolved to face new threats and opponents. He describes in great detail the various fortifications the legions constructed and how they defended them. The book includes more than 500 illustrations and maps.

The Battleships of the Iowa Class: A Design and Operational History (Philippe Caresse, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2019, 522 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $120.00, hardcover)

The Battleships of the Iowa Class: A Design and Operational History (Philippe Caresse, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2019, 522 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $120.00, hardcover)

The four Iowa-class battleships—the Iowa, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Missouri—were the pinnacle of American battleship design. Built in the early years of World War II, they entered service just as the battleship was being eclipsed by the aircraft carrier as the chief warship of major navies. Despite this relegation from primacy, battleships still had useful roles to play.

The battleships escorted the carriers, bombarded shore targets in advance of amphibious assaults, and acted as command ships for fleets and task forces. The sheer firepower these ships possessed meant they were retained after the war. They saw service in the Korean conflict, and New Jersey was taken out of reserve to serve in Vietnam. In the 1980s, all four ships were modernized and reactivated in the growing competition with the Soviet Union during the late Cold War. Their final service occurred during the Gulf War.

This attractive coffee-table book is full of photographs, many in color, mixed with line drawings, charts, and informative text. The imagery is well-chosen, drawing the reader to keep turning pages to see what comes next. Extensive data is also provided on the ships’ Cold War upgrades and actions. All four ships ended their careers as floating museums around the United States, and space is devoted to each vessel’s final destination.

Short Bursts

‘Horses Worn Down to Mere Shadows’ The Victorio Campaign 1880 (Robert N. Watt, Helion and Co., 2019, $49.95, hardcover) Apache chief Victorio battled U.S. and Mexican forces in 1880. After initial successes, the tide of war turned against the Apaches and Victorio died in a last stand.

‘Horses Worn Down to Mere Shadows’ The Victorio Campaign 1880 (Robert N. Watt, Helion and Co., 2019, $49.95, hardcover) Apache chief Victorio battled U.S. and Mexican forces in 1880. After initial successes, the tide of war turned against the Apaches and Victorio died in a last stand.

Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (Kevin M. Levin, University of North Carolina Press, 2019, $30.00, hardcover) The author reveals the falsehoods behind the myth that thousands of African Americans fought voluntarily in the Confederate army during the American Civil War.

Demystifying the American Military: Institutions, Evolution, and Challenges Since 1789 (Paula G. Thornhill, Naval Institute Press, 2019, $26.00, softcover) At its beginning, the U.S. military was a distrusted and peripheral arm of government, yet now it is central to American global power. This book explains how and why this change occurred.

The French Army in the Great War (David Bilton, Pen and Sword Books, 2019, $22.95, softcover) This latest volume in the Images of War series contains numerous photographs of French troops in and out of the trenches during World War I. Many of these images have rarely been seen in the English-speaking world.

Roman Conquests: The Danube Frontier (Michael Schmitz, Pen and Sword Books, 2019, $39.95, hardcover) It took Rome more than a century to conquer the Dacians. This work covers those campaigns in detail.

Inchon Landing: MacArthur’s Korean War Masterstroke September 1950 (Gery Von Tonder, Pen and Sword Books, 2019, $24.95, softcover) The Inchon landings reversed the course of the Korean War in one stroke. This book covers that action with numerous photographs, excellent maps, and a detailed narrative.

Inchon Landing: MacArthur’s Korean War Masterstroke September 1950 (Gery Von Tonder, Pen and Sword Books, 2019, $24.95, softcover) The Inchon landings reversed the course of the Korean War in one stroke. This book covers that action with numerous photographs, excellent maps, and a detailed narrative.

Operation Starlite: The Beginning of the Blood Debt in Vietnam, August 1965 (Otto J. Lehrack, Casemate Publishers, 2019, $19.95, softcover) The Marine Corps’ Operation Starlite was the first major combat action for American troops in Vietnam. Its success caused misplaced optimism about the war effort.

Wellington’s History of the Peninsular War: Battling Napoleon in Iberia 1808-1814 (Stuart Reid, Frontline Books, 2019, $39.95, hardcover) Wellington wrote several lengthy dispatches about the war as it happened. These are combined together for the first time in this volume.

Napoleon’s Admirals: Flag Officers of the Arc de Triomphe, 1789-1815 (Richard Humble, Casemate Publishers, 2019, $45.00, hardcover) The names of 26 admirals are inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. This book tells the story of each, along with a new appraisal of the Anglo-French Naval War.