By Louis Ciotola

As the year 1622 dawned over Germany, things appeared bleak for the refugee “Winter King” of Bohemia, Elector Palatine Frederick V. The entire Protestant cause, in fact, was in its most dire crisis to date in the ongoing struggle against Catholic powers. Just over a year before, the combined might of the Hapsburg-led Imperialists and the Catholic League had smashed the short-lived Protestant rebellion in Bohemia, sending Frederick fleeing into exile. Simultaneously, a Spanish army stormed into Frederick’s native Palatinate and, with the aid of the League, nearly completed the conquest of the entire region, thus making the elector—temporarily at least—homeless. At the start of the new year, the Catholics faced little or no organized opposition.

But as winter melted into spring, Frederick’s prayers for a miracle seemingly were answered when salvation came literally from out of nowhere. Three men, sharing a thirst for war and little else, stepped forward to raise armies and fight in Frederick’s name. The first of these, Count Ernst von Mansfeld, had been a participant in the war since its conception, yet by this time his numerous follies and frequent double-dealing had made him a virtual nonentity. The other two, Christian of Brunswick and George Frederick of Baden-Durlach, were newcomers ready to test their mettle against the seemingly invincible Catholic armies.

With their arrival, Frederick could breathe a sigh of relief, or so it seemed. How long his respite would last was anyone’s guess, for the loyalty, talent, and integrity of the newly arrived Protestant “heroes” were far from unquestionable. Their tale, and the year that it consumed, would prove to be one of wanton brutality and recklessness that stamped an exclamation point on the end of a dying breed of mercenaries.

The “Winter King” in Exile

In November 1619, only one month after Frederick’s coronation as king of the rebellious Bohemians, his new kingdom’s ongoing struggle against the Imperialist Hapsburgs reached its apogee outside the walls of Vienna. A siege of Emperor Ferdinand II’s capital, however, proved impossible after the departure of their Transylvanian allies, and the Bohemian surge slowly began to roll back. During the course of the following spring, the rebel army was able to hold its own, but in July 1620 the Catholic League, led by Bavarian Duke Maximilian II, entered the war by attacking Bohemia’s allies in Austria. Within two months, most of Frederick’s allies were overrun by the Catholic armies, which then invaded Bohemia itself. Frederick had but one remaining army from which to seek help.

That army, commanded by Mansfeld, had been sitting idly in the town of Pilsen since the start of the war. There was little reason for Frederick to expect the lethargic Mansfeld to come to his rescue now, and the king’s apprehensions were quickly justified. Upon the arrival of the Catholic army, Mansfeld offered neutrality to the enemy in exchange for personal indemnity and permission to remain in Pilsen peacefully. The Catholics accepted Manfeld’s offer and turned their might toward Prague, encountering the Bohemian army outside the capital on November 8. The battle, which lasted barely an hour, was a complete disaster for the Bohemians, thanks largely to the skills of a League general, Count Johann Tserclaes von Tilly. Frederick fled Prague just before its capture, earning himself the unflattering nickname “Winter King” for the brevity of his reign.

Making matters worse, Frederick learned that his homeland, the Palatinate, was being overrun by Catholic invaders. Seeking to take advantage of Central Europe’s crisis for its own gain, Hapsburg Spain had allied itself with its Austrian Imperialist cousins during the height of the Bohemian rebellion. Following months of preparation, a Spanish army of 25,000 men under the command of Ambrosio, Marquis de Spinola, crossed the Palatine border from the Spanish Netherlands in August 1620. Spinola moved quickly, driving back the feeble army of the Protestant Union, the coalition of German states created to counter the power of the Catholic League. Within a few days, the Spanish Army completely isolated the Upper Palatinate and blocked reinforcements from the Dutch United Provinces, a traditional enemy of Spain. For the time being, at least, Frederick had no possibility of returning to his electorate.

Mansfeld the Mercenary

There was, however, a bright spot just over the horizon for Frederick and the Protestant cause. The United Provinces, which had already been subsidizing the Bohemian rebels and had flirted with the idea of doing the same for the Protestant Union, was nearing the end of its 12-year truce with Spain. It seemed likely that the Dutch would go to war against Spain at the expiration of the truce. In April 1621 they did just that, declaring war when Spain refused Dutch demands for maintaining the peace.

Frederick’s hopes for a massive influx of reinforcements were dashed when the United Provinces decided not to march to the Union’s relief, opting instead for a defensive strategy. But the wealthy Dutch were willing to continue as paymasters, creating a distraction and keeping Spinola comfortably away from their own homeland. The only problem was that the Union was on its last legs and was not a plausible military diversion. Another force would have to be found. To the great detriment of the Protestant cause, the only candidate for such a diversion was the barbaric and undependable Mansfeld.

Mansfeld was a mercenary in every sense of the term. He initially served the Hapsburgs, both Austrian and Spanish, in Hungary and the Netherlands. His service came to a bitter conclusion when Emperor Rudolf II refused to grant the general what he considered his rightful inheritance upon the death of his father. Snubbed, Mansfeld turned to the Duke of Savoy and also took a simultaneous position in the army of the Protestant Union, thus serving two masters at once. In 1618, Savoy allowed him to march to Bohemia in support of the rebels. Sickly, short, and slightly deformed, Mansfeld was nevertheless a fearless fighter, with an amazing ability to raise armies with great speed. He was also a talented negotiator, a skill that often aided him in his opportunistic tendencies. Still, hiring Mansfeld was always a risk—not only was his utter ruthlessness toward civilians well known, but he had a penchant for abandoning his benefactors at the slightest whim, making him entirely untrustworthy.

Frederick and the Dutch had little choice but to hire Mansfeld. The Protestant Union stood no chance against Spinola, and by spring the Spanish commander had finished off the Protestant army, effectively dissolving the Union. Following this victory, Emperor Ferdinand officially divided the Palatinate between his allies, granting the Lower Palatinate to Spain and the Upper Palatinate to Bavaria.

Fading Hope For the Protestant Cause

Although he now possessed the Upper Palatinate in theory, Maximilian of Bavaria could not dispatch his army into the territory due to a pre-existing treaty with the Protestant Union. Mansfeld would obligingly end Maxmilian’s dilemma. Fueled with Dutch money and back in the service of Frederick, Mansfeld left Pilsen with 15,000 men and crossed into the Upper Palatinate. Maximilian now had an excuse to secure with arms his newest acquisition.

The duke wasted no time sending Tilly and the League army after Mansfeld. Tilly halted an attempt by Mansfeld to re-enter Bohemia and drove the mercenary north into the Lower Palatinate, leaving the Upper Palatinate completely under Maximilian’s control. Despite the check, Mansfeld continued to operate freely in the new theater, marching toward the Spanish army under the command of Spinola’s replacement, Don Gonsalvo Fernandez de Cordoba, and interrupting Cordoba’s siege of Frankenthal.

Wherever Mansfeld went, Tilly followed. The League general raced into the Lower Palatinate and effected a union with Cordoba, but rather than pursue the troublesome mercenary, the Catholic generals chose instead to besiege the electorate’s capital, Heidelberg. By that time, Mansfeld had already settled in Hapsburg Alsace for the winter, beginning an infamous occupation that brought the Alsatians a steady diet of typhus, murder, destruction, and thievery, his soldiers reputedly stealing even Christ figures off local crosses.

As 1621 drew to a close, it was painfully obvious to Protestant leaders that the war was lost. Tilly and Cordoba ran free throughout the Palatinate, and the following spring would surely complete their conquest. Mansfeld’s relatively small army stood no chance—assuming the mercenary would even continue to fight. Meanwhile, the Winter King had taken refuge in The Hague, protected by the only state willing to offer him sanctuary. But the Dutch, unwilling to dispatch an army to rescue his beloved electorate, would do little else for him. Barely two years since being crowned king in Prague, Frederick’s cause was all but lost. Only a miracle could save it.

Rallying Two Protestant Generals to the Cause

Enter not one miracle, but two. The Catholic surge in Germany and Frederick’s vain yet valiant stand finally pulled on the heartstrings of a pair of Protestant generals with the means to turn the tide. The first to step forward and declare for Frederick was the youthful Christian of Brunswick. Brunswick, who possessed an infatuation for Frederick’s wife, Elizabeth, had been a longtime sympathizer of the king, and he now swore an oath to restore the Palatinate to its refugee elector. Brunswick was the current administrator of Halberstadt and a very poor one at that—his true passion was war. As he wrote his mother, “I must confess that I have a taste for war, that I have it because I was born so, and shall have it indeed until my end.”

The second of Frederick’s new heroes was George Frederick, Margrave of Baden-Durlach. A devout 60-year-old Calvinist who was already highly distrusted by the Hapsburgs because of his previous service with the Protestant Union, Baden had decided to assemble his own army shortly after the Union’s dissolution. Brunswick’s declaration made this the best time to do so. Many observers, chief among them Hapsburg Archduke Leopold, suspected Baden’s true intentions, but they were unsuccessful in persuading him to reconsider. On April 25, 1622, the aging Margrave proclaimed his entry into the war and vowed to liberate the Palatinate.

Now Mansfeld had help and Frederick had hope. The combined strength of Mansfeld, Brunswick, and Baden, roughly 40,000 men, was enough to challenge Catholic supremacy in the Palatinate. Should the trio prove successful, others waited in the wings to join the Protestant cause with armies of their own. Frederick was so enthusiastic that he decided to venture from The Hague and personally campaign with one of the three men preparing to fight for his restoration. His first choice was Brunswick, but since Brunswick’s army was the farthest away, Frederick reluctantly chose to accompany Mansfeld, who was still ravaging Alsace.

Decisive Repulse at Mingolsheim

The three Protestant forces remained separated, with Mansfeld and Baden sitting along the Upper Rhine while Brunswick was far off in Westphalia. Despite this, Mansfeld was determined to act offensively, and within days he drew up before the 15,000-strong League army at Mingolsheim, alongside the Kleinbach River. Tilly, who was waiting to unite with his ally Cordoba, kept a wary eye on the enemy. When Mansfeld attempted to cross the bridge at Mingolsheim amid a torrential rainstorm in the face of the Catholic army, a golden opportunity presented itself.

Tilly moved quickly on the morning of April 27, hitting the Protestant rear guard waiting to cross the bridge. Mansfeld could save the rest of his trapped soldiers only by unleashing a brutal covering fire with his cannons from the opposite bank and burning Mingolsheim in order to create a smokescreen. Unfortunately, those same cannons were stuck in a thick mud and could not readily be evacuated. To salvage his artillery, Mansfeld decided to take a stand.

Interpreting the Protestant moves as a full-scale retreat, Tilly ordered 5,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry to storm the bridge and pursue the defeated enemy. It was a cruel surprise to discover Mansfeld’s army, still protected by the smoke, waiting for them. A single cannon shot signaled the start of the counterattack, and within moments a living hell came crashing down upon the Catholics. Only the valiant stand of the Schmidt Infantry Regiment allowed the Catholic survivors to scamper back across the bridge. Tilly attempted to rally them but was wounded for his troubles and compelled to withdraw, leaving behind four cannons and 2,000 men.

“The Salvation of the Empire is at Stake”

Although victorious, Mansfeld was in no mood to pursue the ever-dangerous enemy. He opted to wait for Baden, who joined him three days later. With 30,000 men combined, the Protestants had a tremendous local superiority over the League, but disputes over command erupted at once. Tilly, well aware of his predicament, took the precaution of digging into an excellent position at the Wimpfen bridgehead on the Neckar River. Having only recently been bloodied, Mansfeld refused to assault Tilly directly and chose instead to splinter off from Baden and drive a wedge between Tilly and the fast-approaching Cordoba. Glad to see a hated rival go, Baden stayed put, determined to confront Tilly alone and match Mansfeld’s earlier feat at Mingolsheim.

Marching toward the Spanish outpost of Ladenburg, Mansfeld hoped to lure the Spanish into pursuit, but the ploy failed miserably. It was apparent that Baden was going to give battle, and Tilly sent word to Cordoba, imploring him to race to Wimpfen as fast as possible, adding dramatically, “The salvation of the Empire is at stake.” Early on May 5, Cordoba arrived, boosting the Catholic force to 18,000. Baden, however, was not dissuaded by the shift in power and drew up his forces that same day. Desperate for glory, he had no intention of backing down.

The Protestant army at Wimpfen was experienced, but the conglomeration of officers and men had never trained together, disrupting its coordination. It was also hampered by a lack of provisions. Making up for these shortcomings was an intense Protestant zeal flowing through Baden’s ranks that guaranteed a hard fight. The stage was set for the next major battle in the year-long cavalcade of war.

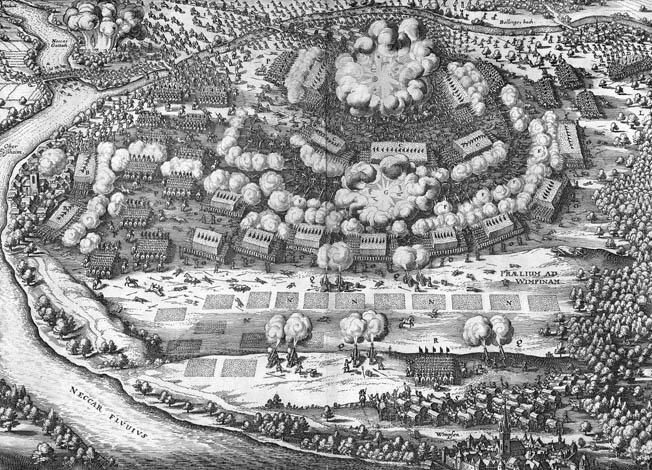

Preparations for the Battle of Wimpfen

The Protestants drew up on a low hill in a semicircle formation. Their left extended to some woods just north of the village of Biberach, while their right sat 600 yards from the Neckar. To the rear was a small stream known as the Rollinger Bach. In front of their formations was a line of 70 battle wagons adorned with spears and armed by guns loaded with grapeshot. Protestants dubbed the line “the Wagonburg.” Immediately behind it were musketeers, strewn out to add greater defensive protection. Artillery was also placed among the wagons. Five infantry battalions arranged in linear style made up the center, with a sixth guarding the right. The mass of the cavalry remained behind the infantry.

The Catholics lined up on the high ground north of the Protestants. The Spanish formed one line of infantry on the right, while the League infantry arranged itself on the left into the traditional square formations known as tercios, four in the front and two in reserve. Cavalry was posted on the flanks and rear. All the Catholic guns were positioned safely behind the army.

May 5 was already quite hot when the opposing armies became fully visible to each other at sunrise. The two sides had been pounding away with cannon fire for the last couple of hours, hoping to draw the others from their position. Tilly and Cordoba remained patient, waiting for an opportunity. At 11 am, Tilly decided the time was right and sent the first four tercios advancing directly on the Wagonburg. Cordoba ordered his front line forward as well. They met an unexpectedly stout defense. Protestant musketeers responded with a hail of fire into the dense Catholic lines from behind their bristling fortifications.

Baden’s Charge

The shaken attackers halted, then retired. By noon, the Catholic forces were back where they had started. The battlefield fell silent as both sides rested their soldiers for the next phase of combat. Then Baden made a terrible mistake. During the temporary respite, he withdrew his troops from the Biberach Woods. Cordoba, eyeing the withdrawal, quickly occupied the advantageous position. When Baden realized his error, he dispatched musketeers to recapture the woods and shield the Protestant assault, which commenced around 2 pm, after he unleashed a second bombardment of the Catholic line.

The Catholics were preparing another attack of their own when Baden unleashed a simultaneous charge of 2,700 Protestant horsemen into the League left, throwing back the Catholic cavalry and threatening to outflank the tercios. In an attempt to relieve the pressure on Tilly, Cordoba continued his share of the offensive, pounding his men against the Wagonburg in another effort to break through. Once again, the Catholics were stopped dead in their tracks.

The Spanish, led by Cordoba personally, prepared to charge Baden’s extended cavalry in an attempt to hit the Protestants while they were exposed. Incredibly, upon its execution, Cordoba was the sole participant in the phantom counterattack. His Walloons timidly refused to follow his lead, and the Spanish commander unknowingly raced through the Protestant horse entirely on his own. Miraculously, he was unharmed. The Spanish had better luck in the Biberach Woods, beating back two assaults by enemy musketeers.

Soon, Baden’s charge ran out of steam. What remained of his cavalry was scattered and disorganized, but the Catholics were in an even more precarious position. Most of their infantry was in utter disarray before the Wagonburg, making them extremely vulnerable to an attack by the Protestant center. Baden, however, declined to press home his advantage. Probably influenced by the remarkable success of his fortifications, he kept his infantry in place, allowing the Catholics time to reorganize and drive off his once-triumphant cavalry, leaving it up to the strength of his defenses to ultimately decide the battle.

Baden’s Army Disintegrates

Around 5 pm, the determined Catholics attacked again, marching straight toward the battle wagons. As before, a deluge of murderous musket fire met the attackers and the advance ground to a halt. Despite the carnage, the Spaniards stood firm, claiming later that a white-robed woman had appeared in the smoke and given them inspiration. But a religious vision was no match for modern weaponry, and it was only a matter of time before the Catholic effort began to collapse.

Then, just as the Spanish seemed ready to crack, a magazine suddenly exploded behind the Protestant lines. Although it did little physical damage, the unexpected blast sent waves of panic through Baden’s ranks, causing the shocked defenders to falter. Smelling blood, the Catholic infantry smashed into the Protestant lines during those crucial few moments of paralysis, driving straight through the Wagonburg and overrunning the cannons. Baden’s infantry attempted to stand, but when their own cannons were turned against them, the exhausted men fled. Only a handful continued to resist, holding out until 9 pm.

The day-long fight cost Baden 2,000 dead, 1,100 captured, and the loss of 10 guns, 70 battle wagons, and 100,000 talers. The Catholics fared much better, suffering only 1,800 casualties, mostly at the Wagonburg. So disparate were the losses that the humiliated Baden hung up his sword. Arriving in Heilbronn, the old Margrave fled to Stuttgart and quit the war. Two-thirds of his remaining force had reformed after the battle, but when their commander announced his retirement, the army disintegrated. A mere 3,000 of them joined Mansfeld, who was fortunate that the victorious Catholics needed a temporary respite after the brutal engagement. He got away with only a minor defeat at the hands of Tilly on June 10, before retreating safely to Mannheim. Barely a month into the campaign, one of Frederick’s three saviors was already eliminated.

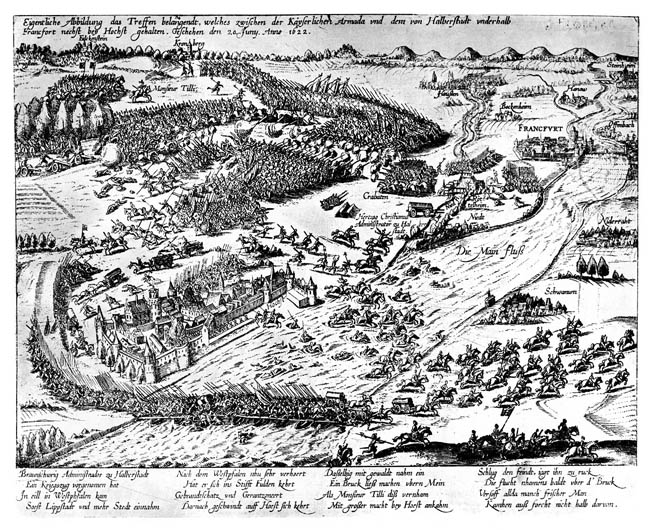

Brunswick’s Army Cornered at Sossenheim

Despite the setback, Mansfeld was soon back on his feet, while Tilly’s focus turned to Christian of Brunswick. Baden’s destruction at Wimpfen and Mansfeld’s momentary check left Brunswick isolated. Mansfeld realized that his last remaining ally was the next Catholic target. If he could reach Brunswick before the enemy, their united force could still turn the tide. As usual, Tilly was one step ahead of his opponents. On June 17, the Catholics won the short race to Brunswick, intercepting him near Hochst, a small town west of Frankfurt-on-the-Main. There they trapped Brunswick, forcing him to fight in order to escape annihilation and initiating the second major confrontation in less than two months.

Brunswick’s army of 15,000 was in no condition to give battle, being outnumbered by 11,000 men and lacking the necessary arms. Fewer than half in his infantry were musketeers, and quality pikemen were in short supply. Furthermore, only one of the three Protestant cannons was operational, while, on the other side, the 26,000-strong Catholic army possessed 19 cannons and recently had been reinforced by a fresh Imperialist division. Given the inadequacies of his army, Brunswick’s only hope was to unite with either Mansfeld or Baden, but the failure of his two allies left him completely alone and hung out to dry.

Brunswick was well aware of his deficiencies. As the Catholics approached, he expected to be attacked and began preparing a position south of the Sulzbach Stream, where he hoped to hold out long enough to allow his baggage to escape. The stream would be his first line of defense. The key point in the line was the village of Sossenheim, specifically its bridge, where Tilly was bound to try to cross the Sulzbach. Brunswick ordered fortifications constructed within Sossenheim and deployed 1,000 men inside the town. To the south, additional redoubts were built and manned by 1,000 infantry. The remaining bulk of the Protestant army ran east to west, with the infantry in front and the cavalry to the rear.

The Catholic army formed to the northeast of the Protestants, just beyond the Sulzbach. The Spanish constituted the right wing, with Cordoba’s infantry massed into two immense tercios and his cavalry on the far right. Three small units of musketeers were posted in the front. Tilly’s infantry consisted of three tercios, one of which was left in reserve. His cavalry manned the extreme left flank and was supported by 500 musketeers.

The opposing armies sat patiently, watching each other closely for nearly three days until, finally, at noon on June 20 the League cannons opened fire. The cannonade had great effect, chiefly because Brunswick was unable to respond in kind. Before long the entire Catholic force was moving forward. The three vanguard Spanish musketeer divisions forded the Sulzbach west of Sossenheim, while League cavalry shot past the town into the Nidda Marsh, and the infantry headed straight for the bridge. The battle for Sossenheim was over within minutes. Brunswick’s men fled without much resistance, ceding the bridge to the enemy. A counterattack succeeded in retaking the town, but the triumph was only temporary. Catholic pressure was irresistible, and the Protestants retired into their redoubts to the south.

As Tilly moved to capture the redoubts, the main Protestant force attempted to cross the Main before the Catholics could complete their encirclement. Upon the reduction of the redoubts, the Leaguers pursued with intense fury. Most of the Protestants managed to make it across the river, but those who did not were slaughtered as the nearing Catholics caused the fear-crazed Protestants to jam the bridge. An untold number of men and horses plunged over the side and drowned in the river.

Following their victory, the Catholics stayed put rather than continuing the pursuit. The consequences of the battle soon became clear to the Protestants. Brunswick had lost roughly 5,000 men, the majority perishing in the Main River, and for a brief time Brunswick was rumored dead. He also lost his precious few cannons. But Brunswick and 8,000 of his men managed to escape to join Mansfeld. Although the Catholics had won the day, they had failed to destroy a relatively weak enemy, allowing it to unite with another Protestant army. It was a mistake they would soon regret.

The Battle of Fleurus

When Brunswick reached his fellow mercenary’s army, he immediately sought out Frederick to complain about Mansfeld’s lack of support, placing the two commanders at odds from the start. Mansfeld was particularly annoyed, knowing that Frederick favored Brunswick. Neither warlord wished to stay together, but under such dangerous circumstances they had no choice. They retreated to Alsace, blaming each other for the year’s disasters and increasing Frederick’s frustration and acute distrust of both men. What upset their patron most was the ghastly way in which they conducted the retreat. Protestant soldiers set fire to nearly every village in their path. Brunswick became known throughout the countryside as the “Mad Halberstadter,” and his cruelty rivaled that of the already infamous Mansfeld. Said an incensed Frederick: “There ought to be some difference made between friend and enemy, but these people ruin both alike. I think these men are possessed of the devil and take pleasure in setting fire to everything. I should be very glad to leave them.”

When he could tolerate no more, the miserable Winter King did leave his disgraceful allies, returning to exile in The Hague. Mansfeld and Brunswick, for their part, thought nothing of abandoning Frederick once he had abandoned them. On July 13, they officially declared their neutrality, but because they refused to disband their armies they were still considered very much the enemy by the Catholics. With safety in numbers, the erstwhile Protestant heroes opted to momentarily set aside their differences and remain united. They had to find a new benefactor to sustain their armies, and since they were close to the French border, they first offered their services to King Louis XIII. The offer, however, was unenthusiastic and the currently neutral French were uninterested anyway, so the pair turned to their old paymaster, the United Provinces.

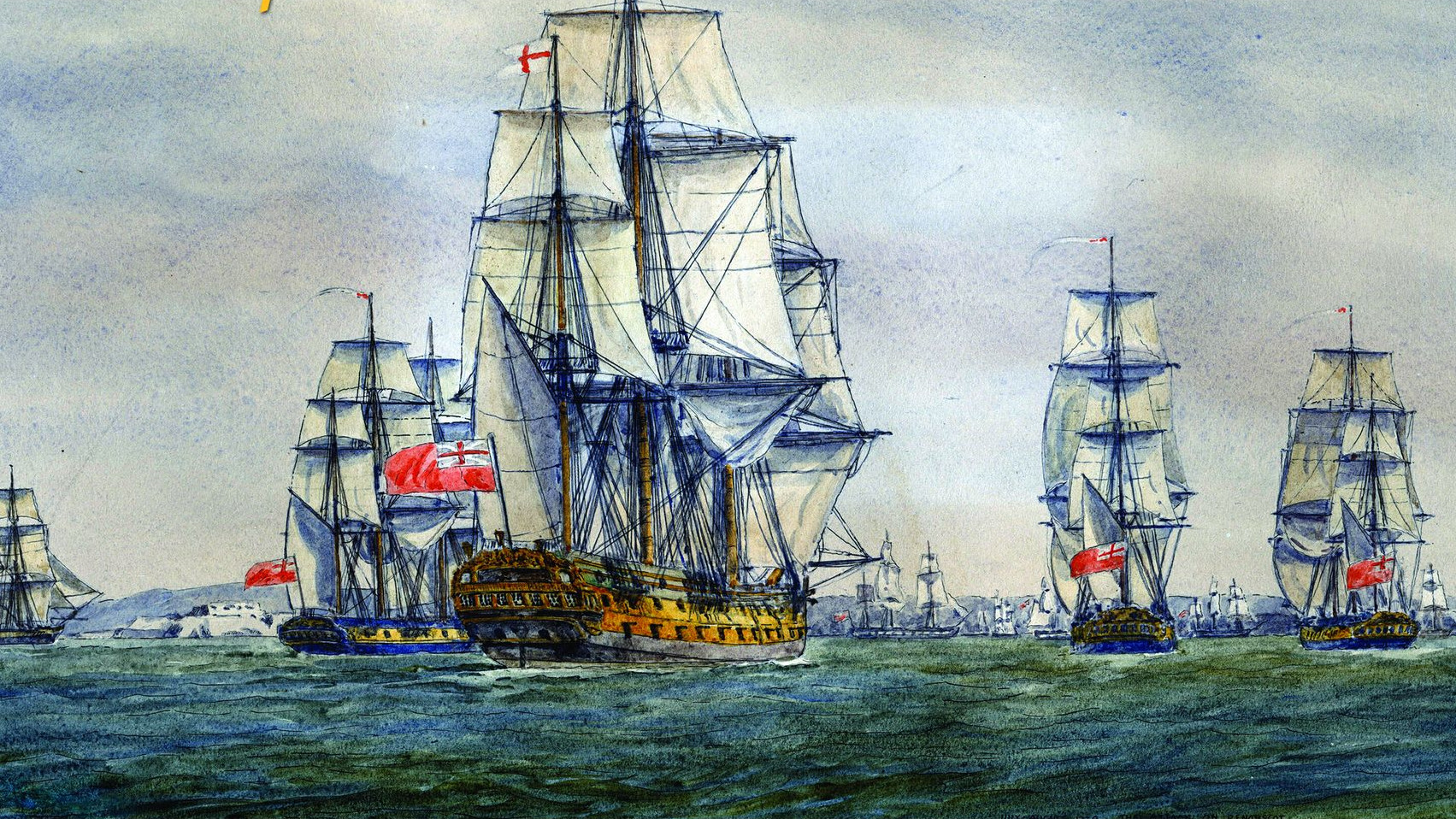

Here they were in luck. With the Spanish enjoying repeated successes in the Netherlands and Spinola currently besieging and close to capturing Bergen-op-Zoom, the Dutch were more than willing to re-employ the two notorious mercenaries, at least until the situation was back under control. The United Provinces promised Mansfeld and Brunswick the necessary subsidies and the Protestant army turned north, excited about the rich lands and plentiful “contributions” it could loot along the way.

Cordoba was unwilling to let his opponents sneak out of Germany that easily, especially since they threatened to impede the progress of his fellow Spaniard, Spinola. Separating from Tilly, Cordoba raced to block their path. On August 26, he caught up with the Protestants at Fleurus and created a blockade with 6,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Mansfeld and Brunswick, with almost 8,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry, along with 10 guns, were determined to break through regardless of the cost. There was no display of tactical brilliance, only the use of brute force. Brunswick led the cavalry forward four times against the Spanish line. All four assaults failed. Finally, five hours into the battle, a fifth charge broke the Spanish line and the remainder of the Protestant army stampeded wildly through the gap.

Mansfeld and Brunswick survived the battle, but Protestant losses were horrendous. More than 5,000 were killed, compared to a minuscule number of Spaniards. Among the casualties was Brunswick, wounded in the arm during one of his bloody charges. When he learned that his arm had to be amputated in excruciatingly painful and primitive surgery, he proudly replied, “Then order the drums to be beaten and trumpets blown, for I advocate doing everything in life in as pleasant a way as possible.” In all, the entire 47-day campaign had cost the Protestants 11,000 men. Mansfeld and Brunswick led a mere 6,000 miserable troops into Bergen-op-Zoom on October 4, but it was enough to compel Spinola to lift the siege.

The Plunder of Heidelberg and the Fall of the Mercenaries

Thus ended Frederick’s year of hope. In one brief campaigning season, all three of his supposed saviors had been vanquished. On numerous occasions, their own inflated egos had caused disaster as they dangerously chose to go it alone rather than serve in close conjunction with one another. Only when all other options had run out did Mansfeld and Brunswick cooperate fully, but by that time it was already too late. Costly military blunders played their part as well, most notably Baden’s failure to clinch his near victory at Wimpfen. The end had come for Frederick’s last possession.

The League, left unopposed in the Palatinate, took full advantage of the opportunity. After quickly reestablishing control over Alsace, Tilly moved on Frederick’s capital, Heidelberg, taking it on September 19 after an 11-week siege. The Catholic soldiers ravaged the city, which Tilly sanctioned as punishment for the obstinacy of the citizens. On November 2, the garrison of Mannheim surrendered. The victorious Catholics shut down Protestant churches and closed Heidelberg University. Since his crowning in Prague three years earlier, Frederick had lost everything. That January, Emperor Ferdinand publicly transferred the Palatine electorate to Maximilian of Bavaria.

As for the three mercenaries, the war was not quite through with them. The following spring, amid a sudden mood for peace, the exasperated Dutch encouraged Mansfeld and Brunswick to exit their territory to seek other lands to plunder. Needing to supply their army with promised loot, the two generals obliged. Mansfeld halted after a short while to pillage the Protestant town of Emden. Brunswick used the occasion to part from his reluctant ally and head for the Lower Saxon Circle, where he hoped to find more legitimate allies and supplies. When Tilly menacingly approached the border, the states of the Circle repudiated their ties with Brunswick and pressured him to depart. Tilly gave chase, catching Brunswick outside the town of Stadtlohn. There, the Catholic champion inflicted a horrific thrashing upon his Protestant victims, killing more than 7,000 men.

By now Mansfeld was in the area, but nothing more than light skirmishing took place. Most of his efforts went toward pillaging East Friesland. As usual, the behavior of his army was nothing short of barbaric. In the meantime, his back against a wall, Mansfeld tried to open negotiations with Tilly, but the Catholics prudently refused to bargain with the unscrupulous mercenary. Mansfeld again offered his services to the French, but again Paris turned him down. With no more moves left to make, Mansfeld handed Emden over to the Dutch and abandoned his army. On April 24, 1624, amid totally unwarranted celebration, he arrived in London, hoping to raise another army with English money.

The Death of Mansfeld

The following year, Protestant hopes underwent another revival, this time due to the intervention of King Christian IV of Denmark, and the three mercenaries again found themselves employed against the Catholics. Just as in 1622, however, each soon met with disaster. Brunswick, a favorite of King Christian, took up arms for the Danish cause in early 1626. Charged with invading Hesse in support of a peasant rebellion, Brunswick failed to incite the state to join him in the war. Instead, the League army pushed into Hesse, crushed the revolt, and forced Brunswick to withdraw to Wolfenbuttel. Depressed, ill, and aged far beyond his 28 years by the torments of war, the “Mad Halberstadter” died on June 16.

Mansfeld, fresh from England, also reappeared in early 1626. Unlike Brunswick, Mansfeld was no friend of King Christian and campaigned independently of the Danes. On April 25, he met his match at Dessau Bridge in the form of Albrecht von Wallenstein, commander of the Imperialist army. In the battle that followed, Wallenstein crushed the mercenary and sent him fleeing. Unperturbed, Mansfeld led his 20,000 men south in a vain attempt to link up with the army of Transylvania, which was threatening to join the Protestant side. When the Transylvanians opted for neutrality, Mansfeld sat alone in Hungary, dead in the water. He resolved to head for the sanctuary of Venice, a march that would take his army deep into the dangerous and disease-ridden Balkans.

The mercenary had survived many battles and countless risks, but this time his luck ran out. While moving through Bosnia, Mansfeld fell ill and died on November 30 in the town of Zara, near the Dalmatian border. Maintaining his martial dignity to the bitter end, the erstwhile scourge of Europe held himself upright between the shoulders of two of his men, determined to die on his feet.

The End of Europe’s Mercenary Era

The last of the three great mercenary commanders made his encore appearance a year later when Wallenstein’s army stormed into Holstein. Baden could not resist rejoining the anti-Catholic crusade, but Wallenstein left little doubt that the old man should have chosen to remain on the sidelines. The Danish navy ferried Baden and his men to Holstein to bolster its defenses, only to have to return soon afterward to retrieve the defeated remnants after the Imperialists easily trounced the expeditionary force at Heilgenhafen on September 26. Baden escaped with his life, but his military career was at an end.

The passing of Mansfeld, Brunswick, and Baden from the scene saw the twilight of the great mercenary tradition. Europe no longer had any place for war-mongering men who raised their own armies and fought for any patron so long as their dues were paid. In the end, the three leaders played a large role in the change. Frederick had put his faith in them during a time of extreme peril, and that faith had been sorely abused. Not only were the three mercenaries sorely lacking in talent and loyalty, but their unchecked brutality proved an unending embarrassment. Frederick’s “heroes,” with their constant blunders and barbaric tendencies, turned out to be more of a liability than a help. In the end, some heroes are just too good to be true.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments