By Al Hemingway

When war with Mexico erupted in 1846, the United States was woefully unprepared. The regular army was well below its authorized numbers and could only field slightly more than 5,000 officers and soldiers. Some of these officers, however, would shine brightly in the ensuing conflict and learn valuable lessons that they would remember all too well when the country was plunged into civil war in 1861.

In his latest offering, The Training Ground: Grant, Lee, Sherman, and Davis in the Mexican War, 1846-48 (Little, Brown, Boston, 2008, 446 pp., notes, index, maps, photos, $29.99, hardcover) historian Martin Dugard examines the roles of these future generals in the Mexican conflict and how some of them would use these hard-earned lessons to gain fame and glory in the Civil War a decade and half later.

Virginia-born Robert E. Lee was an obscure if politically well-connected captain at the outset of hostilities, and he would rise to fame with his daring behind-the-lines exploits. On several occasions, General Winfield Scott would send Lee, an engineer by training, on dangerous scouting missions to find paths or build roads so that Scott’s army could outflank his adversaries. On one such clandestine assignment, Lee was forced to hide behind a log for several hours to avoid being seen by Mexican soldiers filling their canteens at a nearby spring. Lee’s bravery would earn him the respect and admiration not only of Scott, but of many on his staff as well.

A young second lieutenant (later captain) named Ulysses S. Grant, Lee’s counterpart in the next war, would also come under fire and perform heroically, especially during the Battle of Chapultepec. Grant penned numerous letters to his soon-to-be wife Julia describing the battles, personalities, countryside, and attitudes of the American soldiers participating in the fighting. These letters, plus Grant’s insightful memoirs, provided Dugard with valuable information to give readers an accurate accounting of the unfolding events. “The men engaged in the Mexican War were brave, and the officers of the regular army, from highest to lowest, were educated in their profession,” wrote Grant in his memoirs. “A more efficient army for its number and armament I do not believe ever fought in a battle.”

Another officer present at the fighting in Mexico who would play a prominent role as a general officer in the Confederate Army was the eccentric Thomas J. Jackson of Virginia. Assigned to the “flying artillery,” Jackson was everywhere on the battlefield, providing outstanding artillery support to the advancing infantrymen. In the next war, he would win an immortal nickname—“Stonewall” Jackson—before being mortally wounded by friendly fire at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863.

Many other future Civil War leaders also served during the Mexican War and distinguished themselves under fire. Among those seeing action were George Pickett, Joseph Hooker, George B. McClellan, George Meade, Richard Ewell, Abner Doubleday, Ambrose P. Hill, Lewis Armistead, and Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy, to name a few. Braxton Bragg, who would command the major Confederate army in the western theater of operations from Perryville to Chattanooga, was particularly cool under fire. On the flip side, he was detested by his subordinates, who tried to kill him on several occasions. Dugard describes Bragg as “a tyrant, despised by his troops for his fanaticism about discipline and protocol”—traits that would carry over to the Civil War and do much to alienate him from the men he led into battle and, all too frequently, to defeat.

When the Mexican War ended with an improbable American victory in 1848, many of the ranking officers resigned their commissions to enter civilian life. Low pay, slow promotion, and unrewarding duty on the bleak western outposts were underlying factors in their mass exodus. When the nation split asunder after Fort Sumter in April 1861, many of these former officers again donned their respective uniforms and took up arms against each other. When the Civil War ended in 1865, these same officers remained friends. Even a bloody war that nearly tore the country apart could not entirely destroy the esprit de corps instilled into these “band of brothers” on the parade grounds at West Point and the killing fields of Mexico. “The Mexican War was our romance,” Grant remembered.

Tanker War: America’s First Conflict with Iran, 1987-1988 by Lee Allen Zatarain, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2008, 448 pp, illustrations, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Tanker War: America’s First Conflict with Iran, 1987-1988 by Lee Allen Zatarain, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2008, 448 pp, illustrations, index, $32.95, hardcover.

With the current saber-rattling toward Iran, the present administration would do well to take a long, hard look at the first undeclared war between the United States and Iran during the late 1980s. Hostilities with the large Middle Eastern nation likely would be quite different from the often bungled efforts in Iraq. Instead of cowering in their bunkers during the conflict like the Iraqi army in the first Gulf War, the Iranians swiftly retaliated with air attacks against American warships.

In writing Tanker War, author Lee Allen Zatarain used recently released Pentagon documents and numerous firsthand accounts from veterans who had served in the Gulf at that time. The impetus for hostilities between the United States and Iran had started, ironically enough, seven years earlier when Iraq declared war on Iran. Ecstatic with his overthrow of the Shah’s regime, the fanatical Iranian ruler Ayatollah Khomeini called upon his Iraqi neighbors to oust their secular dictator, Saddam Hussein, whom he termed a “puppet of Satan.” Hussein retaliated by launching a massive preemptive invasion of Iran, initiating the greatest bloodbath since World War II.

In 1984, Iran began a series of operations in the Persian Gulf. In retaliation, the Ayatollah’s forces seized Al-Faw, Iraq’s only port on the gulf and threatened Basra, Iraq’s second largest city. Iran’s banzai-style assaults were repelled with horrendous casualties. The cost of the war, in terms of human life and money, was devastating to both countries.

The United States became actively involved when the belligerents began attacking neutral vessels transporting oil from the region. In March 1987, 11 Kuwaiti ships were reflagged under the Stars and Stripes to provide protection from air attack by Iraqi or Iranian planes. That May, the USS Stark was struck by a pair of French Exocet missiles, fired from an Iraqi jet, killing 37 crew members and wounding 21 others. The “Tanker War” soon escalated, with covert operations and the largest naval convoy since World War II. It was dubbed Operation Earnest Will. Tensions in the Gulf increased as each side poised for action.

In April 1988, after one American ship was disabled by a mine, the U.S. Navy planned retaliatory strikes against Iranian oil platforms. In Operation Praying Mantis, a naval force sank two Iranian vessels and three speedboats. It was the largest naval action since the end of World War II and the first surface-to-surface missile engagement in the Navy’s history.

Zatarain has certainly done his homework, producing a compelling account of the military action in the region as well as the behind-the-scenes political intrigue. In doing so, he delves into a tragic incident involving the USS Vincennes. In July 1988, Vincennes erroneously shot down an Iranian civilian airliner thinking it was an F-14 fighter jet. Although the United States government never apologized publicly, it did eventually pay millions of dollars in benefits to the families of the 290 Iranians killed aboard the aircraft.

By 1989, the “Tanker War” was over. The long and bloody Iran-Iraq conflict had ended as well. Within a few years, coalition forces would again see action in the gulf after Hussein invaded Kuwait in the summer of 1990. Following the conclusion of the first Gulf War in 1991, the American public demonstrated little interest in the region. It was not until the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that the American people took notice once again.

Although America’s focus since then has been on Iraq and Afghanistan, Iran is dangerously close to becoming an active participant in the fighting. Self-described “war president” George W. Bush would be well advised to heed the words of one Iranian official, who pointed out: “It is easier entering the Gulf than leaving it.”

The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: U.S. Marines in World War I by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 128 pp., illustration, index, $19.95, softcover.

The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: U.S. Marines in World War I by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 128 pp., illustration, index, $19.95, softcover.

In his new book, retired Marine Colonel Dick Camp pays homage to the leathernecks who fought and died at the Battle of Belleau Wood in 1918. The book is accompanied by 100 photographs depicting the savage fighting encountered by the American forces in the hellish terrain located just outside Paris. There the Marines, attached to the U.S. Army 2nd Infantry Division, were given the arduous assignment of halting the German advance toward the French capital. It would be their first combat in the war. The Germans were amazed at the excellent marksmanship ability of the “youngsters in the forest green uniforms.” This shooting ability would play a pivotal role during the operation.

The taking of Belleau Wood cost the Marines dearly. Thousands would die and countless others would sustain serious wounds. The cost would be worth it; young Marine officers would learn valuable lessons that they would utilize during the next conflict. Future Corps commandants such as Lemuel Shepherd, Clifton Cates, and Thomas Holcomb would forever remember the firsthand experience they received at Belleau Wood and apply that experience ably when they faced the Japanese in World War II.

On Their Own: Women Journalists and the American Experience in Vietnam by Joyce Hoffman, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 448 pp., illustrations, index, $26.00, hardcover.

On Their Own: Women Journalists and the American Experience in Vietnam by Joyce Hoffman, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 448 pp., illustrations, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Vietnam was a war of many firsts. It was America’s first truly integrated war, where African Americans fought alongside whites on a large scale. It introduced the nation to numerous terms and strategies, some good and some bad, that have became a part of the American psyche. The conflict also witnessed a large corps of female journalists accompanying soldiers into combat. Many of them played an instrumental part in reporting the war and then wrote books recounting their experiences while serving in Southeast Asia.

Perhaps the best-known of the women journalists in Vietnam was the legendary Dickie Chapelle. She became a favorite of the Marines and traveled with them on some of their combat operations. Sadly, Ms. Chapelle was killed when she stepped on a land mine in 1965. She remains the only female correspondent killed in action during an American conflict.

The author has done a superb job of telling the tale of a large group of relatively unknown women who braved the gender barrier and ventured into a war zone to cover the fighting.

Duffy’s War: Fr. Francis Duffy, Wild Bill Donovan, and the Irish Fighting 69th in World War I by Stephen L. Harris, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2008, 434 pp., illustrations, index, $19.95, softcover.

Duffy’s War: Fr. Francis Duffy, Wild Bill Donovan, and the Irish Fighting 69th in World War I by Stephen L. Harris, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2008, 434 pp., illustrations, index, $19.95, softcover.

No other chaplain in World War I gained more notoriety than Father Francis Duffy, chaplain for the famed Irish-American regiment the “Fighting 69th,” later redesignated the 165th Infantry. Duffy, a professor of psychology and ethics at St. Joseph’s Seminary in New York, joined the regiment when it headed overseas. Aboard the troopship, he would have doughboys lined up “as long as the mess-line” to hear confessions, and would say Mass at an altar constructed from a long plank sitting atop two nail kegs.

Father Duffy’s presence on the battlefield was nothing short of inspirational. He consoled the wounded and knelt over the bodies of the dead to give them their final rites. For his heroism, Dufy would be presented with the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest military award. The book is a remarkable tribute to the memory of Duffy and the unit’s equally legendary commander, William “Wild Bill” Donovan.” Harris has tracked down old diaries, gleaned period newspapers, and found letters from those who served in the regiment to tell the Fighting 69th’s illustrious history.

Destroyer Captain: Lessons of a First Command by Admiral James Stavridis, USN, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 202 pp., photos, $22.95, hardcover.

Destroyer Captain: Lessons of a First Command by Admiral James Stavridis, USN, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 202 pp., photos, $22.95, hardcover.

It takes a special individual to successfully command a warship in the U.S. Navy. Running the vessel in the most efficient manner and keeping her in top condition in the event of war are constantly on the mind of the captain. Equally important is gaining the respect of the men who serve under the commanding officer. Without that respect, morale will disintegrate and the efficiency of the ship will ultimately suffer.

Admiral James Stavridis, current head on the U.S. Naval Southern Command, has written an intriguing book dealing with his tenure as commanding officer of the USS Barry, at that time a brand new Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer. From 1993 to 1995, Stravridis and his 340-man crew logged more than 150,000 nautical miles and participated in United Nations operations off Haiti in the fall of 1993, the embargo in the Balkans in the summer of 1994, and combat duty in the Persian Gulf.

Due to naval downsizing in the 1990s, surface vessels such as the Barry saw more and more sea duty as the number of ships being constructed by the Navy declined. During his 27 months at the ship’s helm, Stavridis estimates that he and his men were away from their home port an incredible 75 percent of the time.

Stavridis’s book is an insightful read for those who enjoy tales of the sea and want to get a close look at what it was like for a young officer sailing the seas in the turbulent days of the late 20th century.

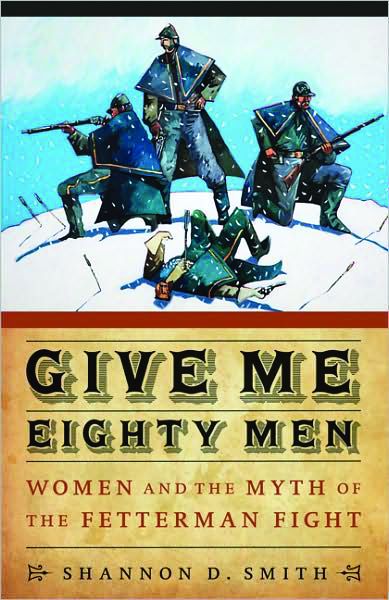

Give Me Eighty Men: Women and the Myth of the Fetterman Fight by Shannon D. Smith, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, 2008, 237 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Give Me Eighty Men: Women and the Myth of the Fetterman Fight by Shannon D. Smith, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, 2008, 237 pp., photos, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Myths have a way of becoming reality. Such is the case in the Fetterman Massacre in December 1866, when U.S. Army Captain William J. Fetterman rode into a “perfectly executed” ambush by Ogala Sioux not far from Fort Phil Kearney in present-day Wyoming. The Indians, upset because white settlers were traveling through their lands after the discovery of gold in Montana, attacked wagons, working parties and trappers in retribution.

Colonel Henry B. Carrington, a political appointee with no prior combat experience, was in command at the fort. Fetterman, by contrast, was a seasoned veteran of the Civil War. The men disagreed and did not get along. Fetterman, described as arrogant in nature, allegedly told Carrington: “Give me eighty men and I could ride through the entire Sioux nation.”

When a wood train was attacked, Carrington quickly dispatched Fetterman. Instead, he was ambushed and his entire command was wiped out. In the ensuing investigation, Carrington’s wife and ex-wife came to his defense, saying it was Fetterman’s arrogance that caused the massacre. He disobeyed direct orders from Carrington not to cross Lodge Trail Ridge, which would dangerously expose his men to attack, they charged. Due to the convincing testimony of the two ladies, Carrington was eventually exonerated of all blame in the tragic incident.

Smith’s research has led her to a different conclusion in the case. She discovered that Fetterman, a bachelor with no family, actually respected the Sioux and their superb fighting abilities. She claims the women “carefully manipulated the public perception of this event and left a permanent and inaccurate imprint on the historical record.” Had Fetterman had a wife or mother to step forward to defend his honor, Smith says his name might have been cleared. Instead, he has become linked to another officer who was killed and his entire command obliterated—George Armstrong Custer—but whose spouse, Libby, carefully protected his image for years after his death.

Empty Casing: A Soldier’s Memoir of Sarajevo Under Siege by Fred Doucette, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, Canada, 2008, 228 pp., photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Empty Casing: A Soldier’s Memoir of Sarajevo Under Siege by Fred Doucette, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, Canada, 2008, 228 pp., photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can strike even the most hardened soldier. After three decades of honorable service in the Canadian Army, Fred Doucette retired. Although now a civilian, the horrific events he witnessed in Bosnia would haunt him forever.

PTSD is not new to war veterans. It has been called soldier’s sickness, shell shock, and battle fatigue. It can be triggered by the most innocent of things. In Doucette’s case, he was sipping a cup of coffee in a mall when he observed a small boy looking for his mother. The vulnerable expression on the child’s face mentally transported Doucette back to Bosnia, where he had served in the mid-1990s as a member of a Canadian peacekeeping force. It reminded him of the countless refugee children left homeless by the bloody conflict. The needless genocidal killings and mass graves left an indelible mark on Doucette’s psyche. His book is a plea for returning soldiers not to be “discarded like an empty casing and left on the battlefield to disappear into dust.”

How the Barbarian Invasions Shaped the Modern World: The Vikings, Vandals, Huns, Mongols, Goths, and Tartars Who Razed the Old World and Formed the New by Thomas J. Craughwell, Fair Winds, Beverly, MA, 2008, 320 pp., photos, index, $19.99, softcover.

How the Barbarian Invasions Shaped the Modern World: The Vikings, Vandals, Huns, Mongols, Goths, and Tartars Who Razed the Old World and Formed the New by Thomas J. Craughwell, Fair Winds, Beverly, MA, 2008, 320 pp., photos, index, $19.99, softcover.

It is unfathomable how someone like Attila the Hun, an untamed, barbarous individual, could possibly be responsible for positively altering the history of the world. But that is exactly what author Thomas J. Craughwell maintains. Out of the burning rubble of countless villages and cities ravaged by Attila emerged modern Europe. One event logically followed the other, even if Attila certainly had no intention of bettering the lives of his victims.

Genghis Khan, another example cited by Craughwell, captured European engineers, builders, scientists, artists, and other craftsmen and had them teach their skills to the Mongols. He also wisely opened the Silk Road and traded with Asia Minor, North Africa, and Europe. Khan was no ordinary barbarian who looted and plundered for the fun of it. His far-reaching ideas included nation building and he sorely desired his people to be educated. Craughwell writes convincingly about the barbarians’ exploits and “how they set off a string of events that resulted in the world we know today.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments