By Michael D. Hull

Between September 1939 and November 1941, the German Army inflicted crushing defeats on Polish, Dutch, Belgian, Norwegian, French, British, and Soviet Armies, achieving in a matter of months what had been impossible during four bloody years of attrition on the Western Front in 1914-18.

In the six years of World War II, the Wehrmacht conquered most of Western Europe and the coast of North Africa before being destroyed in the spring of 1945 in the rubble of Adolf Hitler’s “Thousand-Year Reich.” Well trained, equipped, and disciplined, the German Army was one of the most effective and ruthless fighting machines in history, and once unleashed, it swept all before it. Its officer corps and high command were second to none in clear thinking and professionalism.

In the blitzkrieg of the spring and summer of 1940, the Wehrmacht bludgeoned through the Low Countries, pushed the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk, and humiliated the French. It was far ahead of its foes in technology, coordinated ground-air tactics, and aggressive motivation, yet the early victories made Hitler and his army overconfident. They had not expected the Allies to fold so quickly and soon became drunk on success, as British historian Tim Ripley explains in his authoritative and impressive study, The Wehrmacht (Fitzroy-Dearborn-Routledge, New York, 2003, 352 pp., 180 photographs and colored maps, glossary, index, $95, hardcover). It is part of Fitzroy-Dearborn’s series, The Great Armies.

Out of the euphoria came Hitler’s decision to invade Russia on June 22, 1941, and it was a folly of monumental proportions that sealed the fate of both the Wehrmacht and the Führer’s empire. Powerful as it was, Nazi Germany could not sustain a war on two fronts for long.

The Wehrmacht served an evil cause, says the author, and once it had begun to exterminate Russian civilians and Jews on a large scale, there was no turning back. Hitler’s generals and soldiers were willing participants in the murderous enterprise. Soon, Germany was in no position to match the industrial and human resources of her enemies, and the Wehrmacht was forced onto the defensive everywhere.

This handsome, lavishly illustrated volume is a comprehensive overview of Hitler’s army that demands a niche in every World War II library. It is lucid, literate, and immensely detailed, though marred—as are so many books nowadays—by a number of proofreading flaws.

There is no doubt that the Wehrmacht was one of history’s great armies, Ripley writes, and its hard-fought victories and defeats will be studied by soldiers and scholars for years to come. But it was also an army that sold its soul to the most evil regime of the 20th century. The able generals, such as Kesselring, Guderian, Rommel, Manstein, Rundstedt, Model, Manteuffel, Hube, Senger, and Vietinghoff, were guilty of a moral weakness that was a major factor in Germany’s ultimate defeat, the author concludes. As Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence said of them at the 1945-46 Nuremberg Trials, “They have been a disgrace to the honorable profession of arms.”

This is a rewarding work.

Recent and Recommended

Major General Maurice Rose by Steven L. Ossad and Don R. Marsh, Taylor Trade Publishing, Lanham, Md., 2003, 425 pp., photographs, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Major General Maurice Rose by Steven L. Ossad and Don R. Marsh, Taylor Trade Publishing, Lanham, Md., 2003, 425 pp., photographs, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Born in Middletown, Connecticut, and raised in Denver, Colorado, Maurice Rose never attended college, enlisted as a private in the National Guard, and sailed to France in May 1918, as a company commander with the U.S. 89th Infantry Division.

Two and a half decades later, after duty in Panama, brief service as chief of staff to General George S. Patton Jr.’s 2nd Armored Division at Fort Benning, Georgia, and leadership of a combat command in North Africa and Sicily, Rose was back in France commanding the hard-fighting 3rd Armored (“Spearhead”) Division of the U.S. First Army and earning a reputation as a fearless warrior. Leading always from the front, the son and grandson of rabbis was known as “a real soldier’s soldier” and one of the outstanding armor leaders of World War II.

Yet, after his tragic death on March 30, 1945, when his column was chopped up by Waffen SS panzers on a road near Hamborn, Germany, there was little available for the historical record on Major General Rose except for a few reports and memoranda. Letters to his wife did not survive, and his personal effects were reportedly “lost in a flood in Kansas.”

The highest ranking American Jew ever killed in action, he was one of the war’s ablest yet almost forgotten officers. It was a daunting prospect for a biographer, but Steven Ossad and Don Marsh persevered, dug, and wrote this fully documented, meticulously detailed, and absorbing study. It is a rewarding and inspiring portrait.

The authors show that, after attracting attention by negotiating a large-scale German surrender in Tunisia in May 1943, “Mustang” Rose was hand-picked to lead the 3rd Armored Division just after the Normandy breakout. His record during the first two months of the Northwest Europe campaign was a model of battlefield success. During Operation Cobra in late July 1944, Rose served as the catalyst of General Omar N. Bradley’s decision to move on Avranches.

Constantly issuing radio orders to “keep pushing, keep moving,” General Rose acted as his own scout and forward observer as he rode into battle in his jeep alongside his Sherman tankers and infantrymen. Ever the “old cavalryman,” he “rode to the sound of the guns.” Like Patton, he knew how to meld effectively armor and supporting artillery and infantry units, as this narrative makes plain. The authors take the reader along with Rose’s division—the lance tip of Lt. Gen. Joseph Lawton Collins’s VII Corps—as it rolled eastward across France and Belgium, breached the Siegfried Line, endured the static battles in the fall of 1944 and the crucible of the Bulge that winter, and captured Cologne in March 1945.

Tall, handsome, and taciturn, General Rose was always dressed immaculately, even in combat. Collins said that he was “a commanding figure who claimed instant respect from officers and men alike,” and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander in Europe, called him “one of our bravest and best.”

On March 29, 1945, the day before its commander was killed, the Spearhead Division made the longest enemy-opposed armored drive, more than 150 kilometers, in military history. This resulted in the Ruhr Pocket encirclement, in which more than 350,000 German troops were captured. The action was dubbed the “Rose Pocket” and was the only major action in the war to be named for a U.S. general.

This splendid biography brings General Rose and his division to life, affording popular recognition that is long overdue. Ossad is working on a study of General Bradley, and co-author Marsh served under Rose. The foreword is by respected historian Martin Blumenson.

Air War Over Europe by Chaz Bowyer, Casemate, Havertown, Pa., 2003, 229 pp., 50 photographs, $22.95, softcover.

Air War Over Europe by Chaz Bowyer, Casemate, Havertown, Pa., 2003, 229 pp., 50 photographs, $22.95, softcover.

At the height of the world’s first-ever aerial campaign over the Western Front in 1917, General Jan Smuts, the doughty South African warrior-statesman, declared, “It is important that we should not only secure air predominance, but secure it on a very large scale; and, having secured it, we should make every effort to maintain it for the future.”

And that was what happened just over two decades later, as the Allied and Axis air forces struggled to dominate the skies over Europe, the Mediterranean, Russia, and the Far East in 1939-45. World War II saw clashes of winged armadas on a scale that would have seemed impossible to Smuts and his contemporaries.

The broad sweep of World War II fighter and bomber operations, with focus on the European Theater, has been chronicled by Chaz Bowyer, the author of a host of first-rate books on the history of the Royal Air Force. Detailed yet concise and scholarly yet gripping, this is a masterly study. He explains how the German Luftwaffe attempted initially to conquer the skies, and almost succeeded, until it was defeated by Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires in the summer of 1940, preserving Western freedom when Great Britain stood alone. Then, both sides launched raids that inflicted great devastation and human suffering, as German bombers blitzed British cities in 1940-42 while RAF Bomber Command Short Stirlings, Handley-Page Halifaxes, and Avro Lancasters returned the favor with costly vengeance.

By the time U.S. Army Air Forces Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators achieved momentum with their punishing daylight missions, Germany found itself increasingly defenseless. The Battle of the Ruhr (the German industrial heartland) saw more than 18,500 Allied sorties flown, with the loss of almost a thousand aircraft. The author offers lucid descriptions of aerial support for ground and naval offensives; the V-1 and V-2 rocket raids on southern England; the development of aircraft types, and the gallantry and sacrifice of bomber and fighter airmen on both sides.

Threaded with reliable analysis, this is a crackling narrative.

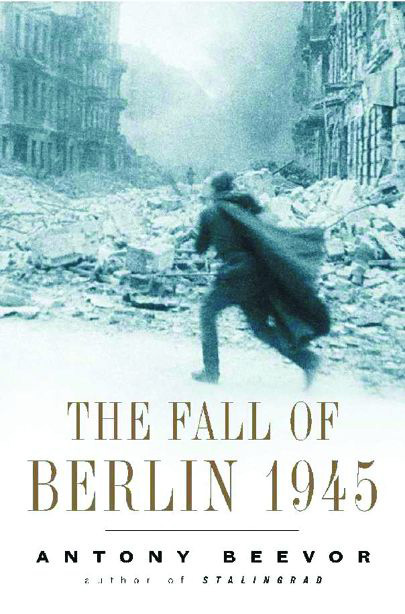

The Fall of Berlin 1945 by Antony Beevor, Penguin Putnam, New York, 2003, 490 pp., 49 photographs, 16 maps, notes, index, $16, softcover.

The Fall of Berlin 1945 by Antony Beevor, Penguin Putnam, New York, 2003, 490 pp., 49 photographs, 16 maps, notes, index, $16, softcover.

When the Red Army finally reached the frontiers of Nazi Germany in January 1945, there was much to avenge.

The guillotine of Soviet retribution would soon fall upon all Germans, soldiers and civilians, women and the elderly, and the organized fury would be unprecedented in history. Frenzied by three and a half bitter years of destruction and suffering at the hands of the Wehrmacht, the SS, and the Luftwaffe, the Russians had dreamed of vengeance two years before. On February 1, 1943, an angry Soviet colonel collared a group of emaciated German prisoners in Stalingrad. Pointing to the ruined buildings and rubble all around, he shouted, “That’s how Berlin is going to look!”

And the Soviet dream came true, with massive armies driving the German invaders from their farthest point of eastward advance all the way back to the heart of the Third Reich. When Marshal Josef Stalin announced a major offensive involving six million troops in January 1945, the Western military commanders, recovering from the Battle of the Bulge, were skeptical, while the manic, twitching German Führer, Adolf Hitler, dismissed reports of the Soviet buildup as “imposture” and continued to overestimate the strength of his own battered forces.

Nevertheless, after a massive bombardment and three assaults on January 12, the Red Army pushed across the River Oder, cleared Silesia and Pomerania, and attacked toward Berlin, the River Elbe, and Czechoslovakia. Marshal Ivan Konev’s army reached the outskirts of the German capital on April 19, 1945, and by month’s end, the Red Army had encircled the city.

Then, suburb by suburb and house by house, Soviet armored, infantry, and artillery units battered their way relentlessly through Berlin, as chronicled by Antony Beevor, a veteran of the British 11th Hussars, in this masterpiece of historical writing. Gracefully crafted and diligently researched, it is the definitive study of one of the most terrible battles in World War II.

Here is harrowing detail

of the havoc wrought by Stalin’s legions, tanks crushing refugee columns, wide-scale pillage, the mass rape and murder of civilians, and awesome destruction as pathetic remnants of the Wehrmacht, SS, Home Guard, and Hitler Youth were overwhelmed by eight Soviet armies. Hundreds of thousands of women and children froze to death or were mutilated, and more than seven million refugees fled west toward the more merciful British and American armies. This is a saga of fanaticism and savagery, of pride and stupidity, and of endurance and sacrifice.

Beevor, whose best-selling study on Stalingrad was published in 23 languages, is a meticulous scholar and born storyteller, and in this book he conveys with thunderclap effect the pity and folly of war.

Hunters in the Shallows by Curtis L. Nelson, Brassey’s, Bangor, Maine, 2003, 243 pp., 30 photographs, 4 maps, notes, index, $16.95, softcover.

Hunters in the Shallows by Curtis L. Nelson, Brassey’s, Bangor, Maine, 2003, 243 pp., 30 photographs, 4 maps, notes, index, $16.95, softcover.

When the four remaining PT boats of Lieutenant (j.g.) John D. Bulkeley’s U.S. Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 3 pushed out into Manila Bay on the black night of March 11, 1942, they were starting a 36-hour voyage that became the stuff of naval legend.

For 560 miles southward from Corregidor to Mindanao, the boats carried a famous passenger, General Douglas A. MacArthur, and his wife and son. With American and Filipino resistance crumbling on the Bataan peninsula, MacArthur had been ordered out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He would fly by B-17 bomber from Mindanao to Australia, where he was to plan an Allied offensive in the Southwest Pacific.

MacArthur’s rescue was the first good news to come out of the Philippines, so the press jumped on it. War correspondent William L. White rushed into print with a book, They Were Expendable, which overdramatized MTB Squadron 3’s gallant but limited role in the futile defense of the Philippines. It became a runaway bestseller, and for the rest of World War II the public associated PT boats with heroic feats of David-and-Goliath derring-do. The image was compounded in 1945 with the release of John Ford’s rousing, sentimental screen version of White’s book, starring Robert Montgomery, John Wayne, Ward Bond, and Donna Reed.

With his lively and informative book, Curtis Nelson examines the history of one of the U.S. Navy’s most famous yet least understood vessels. First published in 1998 and now reissued in paperback, this work of scholarship and critical analysis cuts through wartime hype and romanticism to place the PT boats in true perspective. Nelson pulls no punches, pointing out that the fast, maneuverable, 77-foot PTs—constructed of mahogany, plywood, and much glue—were versatile and technically sound, yet unsuccessful as torpedo boats. The Navy, he writes, conceived and built the PT as a torpedo boat, yet it spent relatively little time serving as one.

Citing official records, the author points out that the 464 PT boats serving with the Navy in 1942-45 fired only about 700 torpedoes during the entire war. Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison described the PTs as “useless,” and called their attacks “futile” and “suicidal.” Yet he praised them as gunboats.

Nelson covers fully their operations in the Pacific, the Mediterranean, the English Channel, and the Aleutians, and has produced a crisp, honest, and absorbing history.

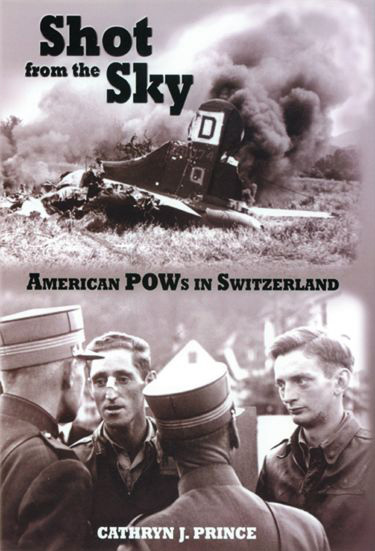

Shot From the Sky by Cathryn J. Prince, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2003, 249 pp., 23 photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Shot From the Sky by Cathryn J. Prince, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2003, 249 pp., 23 photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Men were thrown into filthy, overcrowded barracks where the food was almost inedible and the beds consisted of straw strewn on planking.

Outside, barbed wire surrounded compounds that were patrolled constantly by dogs and guards with submachine guns. The mud was ankle-deep. It sounds like Stalag 17, but it was actually the odious Wauwilermoos internment camp in neutral Switzerland. Out of 1,740 U.S. Army Air Forces personnel interned in Switzerland in 1943-45 after being shot down or forced to crash-land, 947 tried to escape. The 184 who failed to gain their freedom were sent to Wauwilermoos.

Conditions there, and at Les Diablerets and an officers’ camp at Greppen, were almost as harsh as in some German prison camps. Ironically, the airmen could not demand better treatment because the Geneva Accords did not apply to POWs held in neutral countries. But the internment experience of the Americans and some British and Commonwealth airmen in Switzerland differed. Conditions for the majority of internees were adequate and humane, if they obeyed their captors. They were held in vacant hotels in mountain villages and were allowed to interact with the locals.

Hitherto overlooked by historians, the Swiss internment of American fliers is detailed readably in this book by former Christian Science Monitor reporter Cathryn Prince. She does a thorough job of uncovering a sidelight of World War II, although she is unduly critical of the Swiss. The Americans were not starved, beaten, or tortured, despite the fact that a number of them had bombed Swiss cities, including Basel, Schaffhausen, and Zurich, through navigational errors.

Prince claims that the Swiss applied international law in a duplicitous and grossly unfair manner, that no downed German airmen were interned, and that German planes were permitted to refuel at Swiss airfields. But the Swiss were in a difficult position and had more to fear from Germany than from the Allies. For this book to speak of “shocking new evidence” of Switzerland’s “shameful” role is reaching, and smacks of revisionist whining.

The author was apparently aided and abetted by the Veterans Administration, which issued a white paper in 1996 claiming that conditions in Wauwilermoos were “much worse than those in other Swiss confinement camps, and were at least comparable in nature to those of the German and Japanese governments.” Try selling that line to survivors of Wake Island, the Bataan Death March, Singapore, or the Siam Railway.

It was no picnic in some of the Swiss camps, where the diet consisted of potatoes thrice daily or was sometimes so unappetizing that the prisoners vomited at the sight of it, as the author makes clear. But to compare these camps with those of the Germans and Japanese is hard to swallow. Thus, while this book is revealing and well written, it is a bit overstated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments