By Patrick J. Chaisson

Corporal Thomas B. Tucker stood shivering in the bitterly cold night air as he looked down on a ribbon of water that separated his unit from the enemy’s front-line positions. This was the Sauer River, a fast-flowing stream that Tucker—a combat engineer with the 5th Infantry Division—would soon attempt to row his assault boat across while under fire from German machine guns and nebelwerfer rocket artillery.

The Sauer River crossing, which took place in eastern Luxembourg on January 18, 1945, was the 15th such operation conducted by Corporal Tucker’s outfit since it entered combat the previous July. Part of Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third U.S. Army, the 5th Infantry Division, nicknamed “Red Diamond” for its distinctive shoulder insignia, would eventually vault 25 rivers, including the mighty Rhine, before war’s end. Patton even joked that its troops all had webbed feet from so much time spent in the water. Yet Tom Tucker and his fellow Red Diamond soldiers knew their reputation as river-crossing experts meant they would be chosen first for the most hazardous assignments.

This particular mission would require extraordinary courage and stamina from everyone involved. Those G.I.s preparing to leap the Sauer faced both a determined foe and some of the most brutal winter weather ever experienced by American fighting men. Their nighttime assault, conducted in subzero temperatures, thigh-deep snow, and biting winds, nevertheless had to be made. While few who were there understood its significance at the time, the Allies’ final offensive against Hitler’s Third Reich started on the Sauer River.

When Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s panzers struck surprised U.S. forces in the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg on December 16, 1944, the 5th Infantry Division was fighting far to the south in Germany’s Saar River valley. Four days later, as part of General Patton’s audacious counterthrust into Rundstedt’s southern flank, the unit abruptly pulled up stakes and moved into Luxembourg.

Conducted during a blinding snowstorm, this tactical motor march severely taxed the endurance of all those who participated in it. Then the Red Diamond’s riflemen, half-frozen, poorly fed, and exhausted from their difficult journey, immediately launched an attack against overextended German forces. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall marveled at their performance, later writing how “elements of the 5th Inf. Div. which were fighting in the Saar bridgehead on the morning of 20 December moved 69 miles, and were in contact with the enemy … by nightfall.”

By December 29, the Red Diamond Division had fought its way to the Sauer River, a natural barrier separating Patton’s Third U.S. Army from the German Seventh Army. Here, on a line of hills overlooking the river’s south shore, its troops paused to rest, reorganize, and prepare for their next mission.

Led by Maj. Gen. S. LeRoy Irwin, the 5th Infantry Division consisted of some 14,600 fighting men. Its primary maneuver elements, the 2nd, 10th, and 11th Infantry Regiments, were all combat-tested but had recently suffered heavy losses while attempting to take the French fortress city of Metz. Despite an influx of replacements, most rifle companies remained well below their authorized strength.

Backing Irwin’s infantrymen were four battalions of howitzers—the 19th, 46th, and 50th Field Artillery Battalions (FABs) (105mm towed), plus the 26th Field Artillery Battalion (155mm towed). Support commands included the 449th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion, 5th Medical Battalion, and 7th Engineer Combat Battalion (ECB). Smaller-sized ordnance, signal, cavalry, quartermaster, and military-police detachments completed the Red Diamond Division’s organizational structure.

When the 5th Infantry Division moved north during the last days of December 1944, it picked up two armored units—the 737th Tank Battalion (TB) and 803rd Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion—meant to replace other outfits left back at the Saar. It also received a transfer to Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy’s XII Corps.

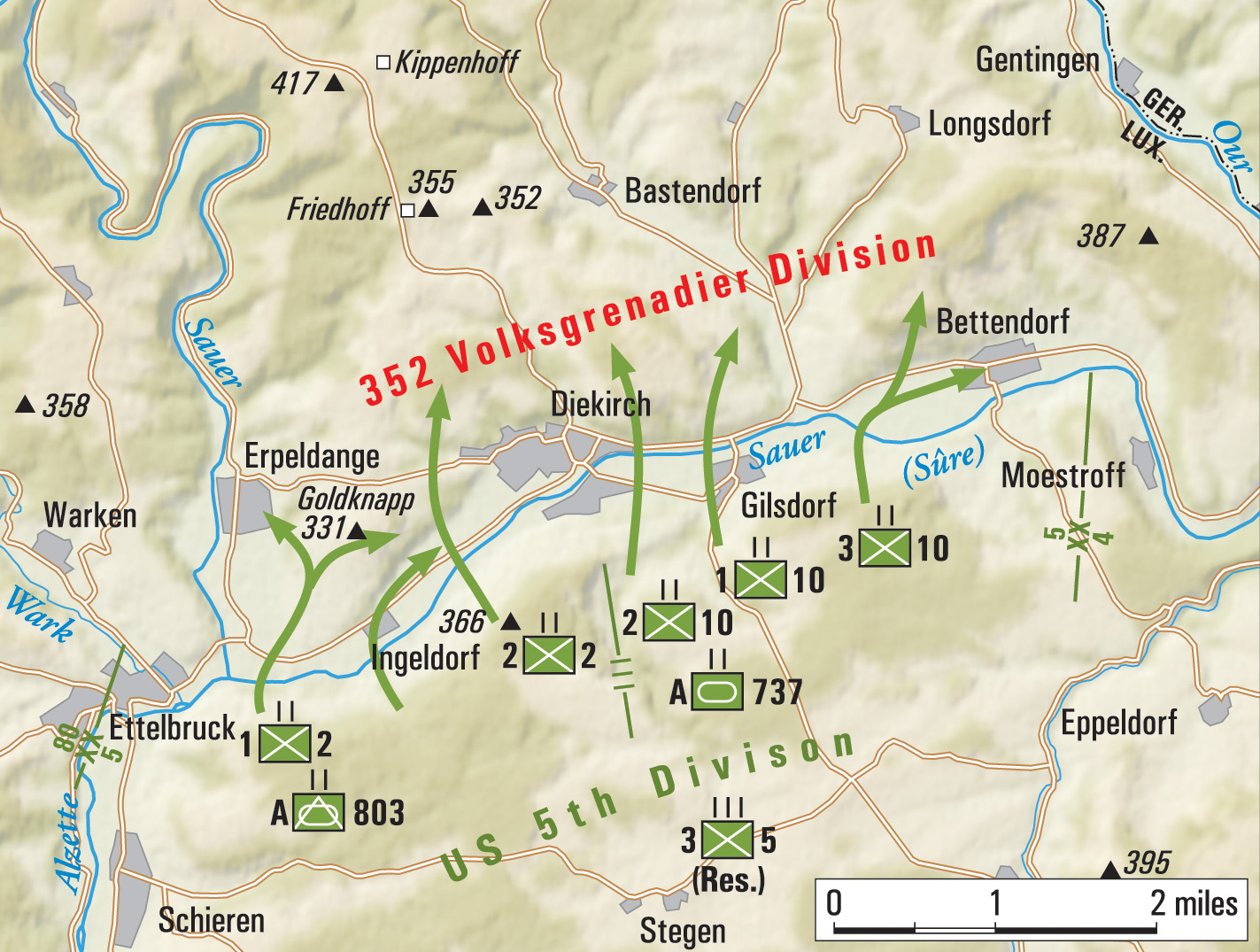

In mid-January 1945, XII Corps (one of three corps making up Third Army) held an L-shaped sector along the southern shoulder of the Ardennes front. Off on the right, orienting east along the Moselle River, the 2nd Cavalry Group and 87th “Golden Acorn” Infantry Division screened the Luxembourg-Germany border. The 4th “Ivy” Infantry Division, badly mauled by Rundstedt’s forces in December, faced north to secure a critical position at the border town of Echternach. On XII Corps’ left flank, the experienced but battle-weary 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division tied in with other Third Army forces then fighting across western Luxembourg and Belgium. In the center, occupying strong positions over the narrow Sauer River, stood Maj. Gen. Irwin’s Red Diamond Division.

The XII Corps remained in a largely defensive posture along this line from New Year’s Day until January 18, 1945. Patton had other priorities. His focus was on reducing the “tip” of the Bulge many miles to the west. The XII Corps’ orders were to build combat power, conduct aggressive patrolling, and prepare for continued offensive operations.

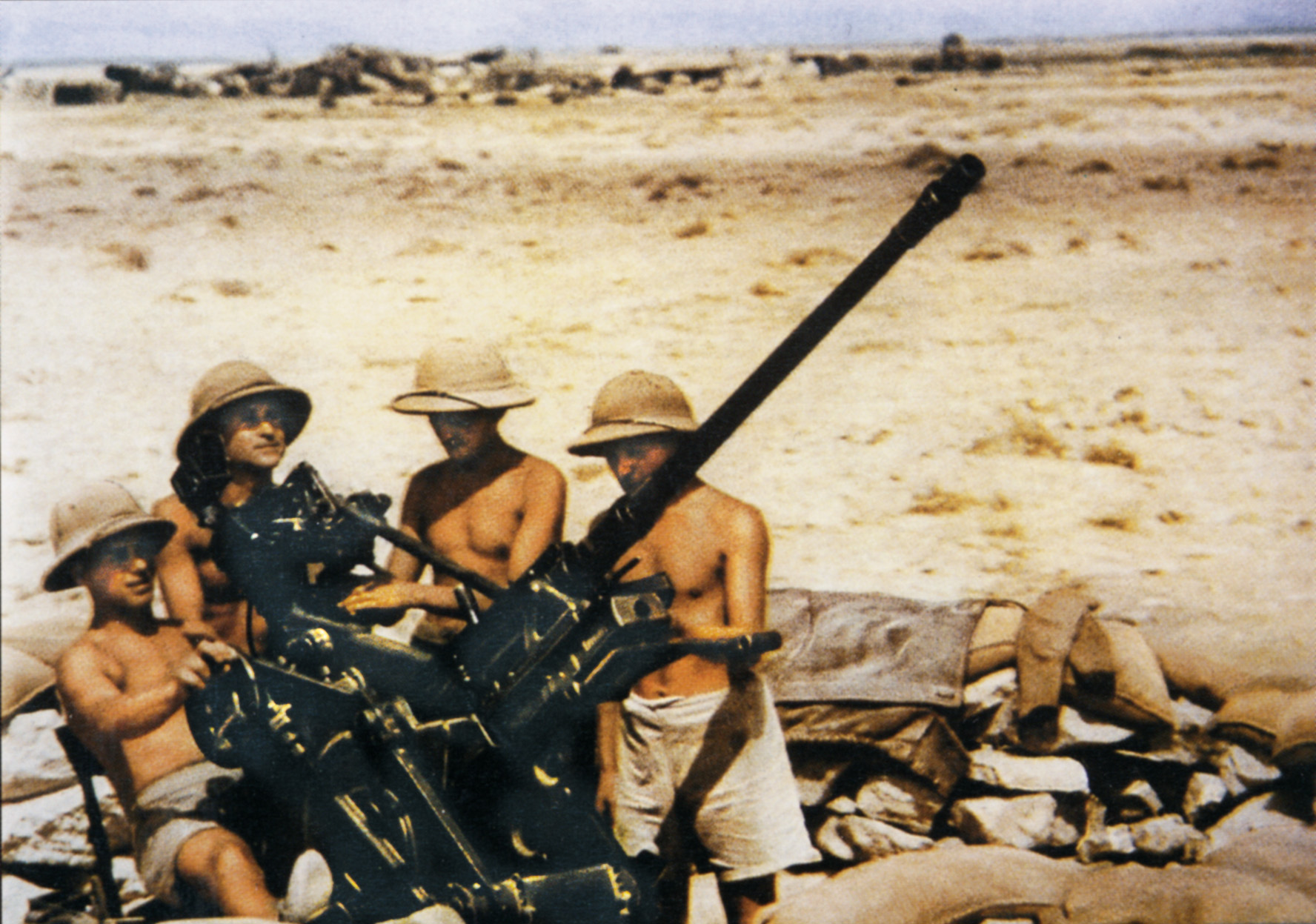

Meanwhile, those G.I.s dug in along the Sauer were fighting two cruel enemies—the German Army and the weather. At present, dealing with Luxembourg’s unnaturally harsh winter took precedence over the human foe.

Meteorologists had not recorded conditions this severe in 100 years. Thermometers barely reached 32 degrees Fahrenheit during the day, and nighttime temperatures often plummeted to 10 degrees below zero. Frequent storms blanketed the region in up to two feet of snow, while overcast skies and an almost constant wind only compounded the misery.

Frontline soldiers did (and wore) whatever they could to stay warm. Private First Class Jack Davis, a medic in the 10th Infantry Regiment, remembered his uniform included “three pairs of woolen underwear, olive drab pants, shirt and sweater, and a driver’s coat.” Davis also had on thin gloves and two pairs of socks, one he kept dry under his clothes while wearing the other pair.

The elements took a heavy toll on soldiers’ health. Cold-weather ailments—frostbite, trench foot, and the flu—left most rifle companies extremely undermanned, while aidmen were forced to manufacture improvised sleds using captured snow skis so they could evacuate the wounded.

Combat engineers, specially trained to build bridges and handle assault boats, were instead kept busy plowing and sanding roadways so ammunition, rations, and supplies could continue to reach the front. General Irwin considered his engineers as absolutely essential to any successful river crossing operation, but knew he did not possess enough of them. The 5th Infantry Division’s 7th ECB lacked both the personnel and bridge-building equipment required to properly span the Sauer.

More engineers were needed. Fortunately, Maj. Gen. Eddy had assigned to his command the 1135th Engineer Combat Group (ECG), headed by Colonel Alfred Dodd Starbird. It became Starbird’s task to coordinate all bridging activity in the XII Corps zone.

Available engineer assets included the Red Diamonds’ own 7th ECB, the corps-level 133rd and 150th ECBs, and the smaller 509th Treadway Bridge Company. These units would ferry infantry across in wooden assault boats, emplace footbridges, and—depending on conditions—install either metal-framed Bailey or floating “treadway” bridges capable of accommodating armored vehicle traffic. Engineer service troops were also made available to take over certain non-combat duties in the rear area such as snow removal and road repair.

The XII Corps also planned to employ a variety of specialized combat support organizations for this assignment. Companies C and D of the 91st Chemical Mortar Battalion (CMB) fired heavy 4.2-inch mortars capable of laying white phosphorous smoke on the objective, while the 81st Smoke Generator Company could blind enemy observers with smoke pots or fog oil. Military policemen kept traffic moving, medical personnel prepared for the expected influx of combat casualties, and members of a shadowy organization named the 3132nd Signal Service Company readied their “sound cars” for a highly-classified deception mission.

Altogether, Maj. Gen. Eddy gathered thousands of XII Corps soldiers to buttress the 5th Infantry Division’s advance, along with smaller flanking attacks conducted by the adjacent 4th and 80th Divisions. Plans were finalized, recon patrols conducted, and bridging materials brought forward to the crossing sites. H-hour was set for 0300 hours [3:00 am] on Thursday, January 18, 1945.

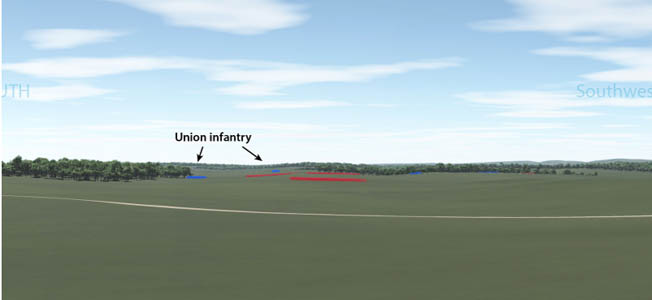

Watching all this activity from observation posts along the Sauer’s northern bank were several thousand riflemen belonging to the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division (VGD). The 352nd VGD, commanded by Generalmajor Richard Bazing, had a critical assignment—hold the “Bulge” penetration’s southern shoulder open so other German formations could withdraw to safety. Its three understrength infantry regiments, the 914th, 915th, and 916th grenadiers, would need to defend an impossibly long sector in rough terrain while enduring the same wintry conditions as did the foe.

General Bazing was additionally hampered by a shortage of ammunition for the hodgepodge of Italian, Russian, and German field pieces with which his 1352nd Artillery Regiment was equipped. Furthermore, most of these guns were horse-drawn and slow to maneuver in snow-covered terrain. More mobile were several batteries of trailer-mounted nebelwerfer rocket launchers, able to launch volleys of high-explosive projectiles and relocate before U.S. guns could respond.

The Germans did have plenty of landmines, though. Their deadly S-mine, or “Bouncing Betty,” propelled itself three feet into the air when tripped, then sprayed a shower of shrapnel in all directions. The wooden “Schü” mine was immune to Allied mine detectors, while improvised booby traps were left anywhere an unwary G.I. might trigger them.

The terrain was well suited for defensive operations. The Sauer (or Sûre in French) River flowed generally eastward for 150 miles through France, Luxembourg, and Germany before emptying into the Moselle. Normally placid and shallow, the Sauer had been transformed by recent winter runoff into a roiling, ice-choked torrent. At the crossing sites, it measured 8-10 feet deep and from 100 to 120 feet across. Steep banks cut the southern edge.

A number of hill masses dominated the northern, German-held, side. Some prominences, like Goldknapp Hill, had a name on military maps, while other peaks such as Hill 383 were identified solely by their height in meters. The region was generally semi-mountainous in nature and heavily forested. A poor road network connected scattered farm communities with the more densely populated Sauer River valley.

Several riverside villages stood within the 5th Infantry Division’s zone, the largest of which was the district capital, Diekirch. Smaller built-up areas included Ettelbruck, along the Red Diamond’s western flank, and Bettendorf on its eastern boundary. The hamlets of Ingeldorf and Gilsdorf offered potential crossing sites partially shielded from direct observation.

General Irwin’s infantrymen also needed to capture several hilltop strongpoints that dominated the valley. German artillery spotters had taken over a number of sturdy dwellings, including the Friedhof and Kippenhof farmsteads, that provided a clear view of the river. Ousting the foe from these ready-made stone fortresses would be no easy chore.

The 5th Infantry Division plan called for two regiments to cross the Sauer in a night attack, then continue their advance north to drive a 12-mile-deep wedge into the German lines. General Irwin believed this scheme, if properly executed, would help trap those enemy forces caught trying to retreat from the now collapsing Bulge. He further instructed, “Maximum use will be made of maneuver to bypass and pinch off fortified heights and towns,” but understood the region’s rugged terrain and deep snow would greatly restrict cross-country movement.

Irwin task-organized his command into three combat teams, each centered on an infantry regiment. The 2nd Combat Team (CT) consisted of the 2nd Infantry Regiment, as well as the 50th FAB, Company C of the 91st CMB, the 737th TB’s Company A, and Company A of the 803rd TD Bn. Company C, 7th ECB, was to put across the first waves using footbridges and assault boats.

The 10th CT had at its core the 10th Infantry Regiment, supported by the 46th FAB, D/91 CMB, B/737 TB, and B/803 TD. Company B of the 7th ECB would get 10th CT’s lead elements onto the far shore. In reserve was the 11th CT, which contained Maj. Gen. Irwin’s remaining infantry regiment as well as the rest of his artillery and armor.

General Irwin divided his area of operations into two regimental zones. To the west, the 2nd CT would cross the Sauer via footbridge and assault boat near Ingeldorf, spreading out to seize Erpeldange, Goldknapp Hill, and Diekirch. The 10th CT was to jump the river four miles eastward at Gilsdorf, its objectives the village of Bettendorf and Hill 383, plus several other hill masses in the north. To preserve surprise, division artillery was prohibited from firing a preparatory bombardment.

Also working to mislead the foe was a top-secret sonic-deception unit. This outfit, the 3132nd Signal Service Company, employed powerful vehicle-mounted loudspeakers that replicated the sounds made by an approaching armored column. Operating under the 2nd Cavalry Group, these tricksters started broadcasting shortly after midnight on January 18 from positions along the Moselle River near Flaxweiler, Luxembourg—19 miles southeast of the actual crossing site. The ruse worked, as German gunners expended a significant amount of precious artillery ammunition against their phantom tanks.

Meanwhile, along the Sauer freezing temperatures and snow clouds combined to create an eerie, whitish fog that helped conceal the American combat engineers and riflemen then moving into position. At 0300 hours, the river crossing commenced.

In the 2nd CT’s zone, Company C of the 7th ECB launched two footbridges, one on either side of Ingeldorf. The crossing east of town did not go well. Combat engineers twice attempted to put in a bridge, but both times were driven off by vigilant grenadiers. In response, infantrymen from the 2nd Battalion “marched down to the river with every gun firing and literally blasted the enemy from his far shore defenses,” as described by the regimental historian. Then they boarded a flotilla of flimsy wooden boats and shoved off.

One of those G.I.s was Pfc. Michael C. Bilder of Company G. “Our boats had just left the riverbank,” Bilder wrote, “when the Germans lit up the area with flares. The opposite bank cleared enough to reveal a full complement of Germans, dug in and well armed. Screams of pain, shouted orders, and noises of every kind filled the air as the enemy poured down fire on us during our journey across.”

Other troops posted nearby began to shoot back, but their reckless fusillades terrified those men in the assault boats. “Crossing with German fire to our front and American fire from our rear was as frightening as all hell,” Bilder recalled, later wondering how anyone could have survived that attack.

With their foe’s attention focused on the eastern crossing, another group of combat engineers successfully emplaced a footbridge over the Sauer on Ingeldorf’s west side. The 1st Battalion raced across it and headed north through thick snowdrifts toward the village of Erpeldange.

In the meantime, 2nd Battalion struggled to expand its tiny foothold on the north shore. Private Charles H. Schroder, a BAR gunner in Company F, had been wounded earlier that day but repeatedly refused medical attention. Continuing to fight despite several painful injuries, Schroeder dueled with enemy machine gunners posted on Goldknapp Hill who had caught his platoon out in the open. From a greatly exposed position, he laid down suppressive fire until a mortar shell struck and killed him.

On another part of the Goldknapp, T/5 Calvin J. Randolph observed three men go down with serious wounds. Unhesitatingly, Randolph, a medic, ran forward to evacuate them. He successfully carried two casualties off the field but fell to enemy bullets while aiding the third soldier.

Schroeder and Randolph were each posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their valor on January 18, 1945.

Dug in on the German-held heights overlooking Diekirch, Private Ulrich Jonath of the 2nd Bn., 914th Grenadiers, witnessed it all. “Under cover of darkness and without artillery preparation,” he wrote, “the Americans were crossing the Sauer in boats to begin the attack.” Jonath observed their progress using his MG42 machine gun’s optical sight. “Through the glass I saw numerous white-camouflaged figures … In no time [we] were ordered to fire, and I shot at the rows of attacking Americans. The group to our left also fired like mad.”

Jonath’s account continued: “Shortly afterward, some of our mortars also fired across the Sauer. Screams were heard. There were many dead men on the slope.”

After daybreak, German howitzers and nebelwerfers roared into action. Projectiles fused to detonate at treetop level plastered the bridgeheads despite all attempts to obscure them with chemical smoke. The 7th ECB’s Corporal Tom Tucker watched in horror as his friend Pfc. Leroy R. Thomas was struck and killed by shell fragments during one of these barrages.

In response, U.S. field artillery began pounding known and suspected German positions north of the river. Although all attempts to install a footbridge on Ingeldorf’s eastern side had failed, infantrymen from 1st and 3rd Battalions, 2nd CT, were able to safely cross west of town. By noon, the Americans had enveloped Goldknapp Hill, isolated the villages of Ingeldorf and Erpeldange, and positioned themselves for an advance on Diekirch.

Four miles downstream, the 10th CT leaped the Sauer at Gilsdorf. First to go over was 3rd Battalion, which started off by “loading men into the assault boats at the top of the slope and shoving the boats downhill like toboggans,” as an official Army historian related. Engineers also tied 150-foot lengths of rope to their watercraft so they could be safely pulled back across for the next wave.

Thanks to a thorough pre-mission reconnaissance, 3rd Battalion’s crossing achieved total surprise. In the pre-dawn murk, American infantrymen moved surely and silently to occupy key terrain on high ground overlooking the village of Bettendorf. By 0600 hours they had reached the objective without a shot being fired.

One sergeant summed up their accomplishment thusly: “To sneak several hundred men across a river right in the teeth of prepared enemy positions, to infiltrate the men through enemy lines carrying heavy machine guns and other noisy equipment and to reach an objective hundreds of yards behind the enemy front line—to do all that isn’t hard, it isn’t clever, it isn’t soldiering, it’s just downright impossible. But we did it.”

Distracted by 2nd CT’s noisy bridgehead to the west, German forces reacted slowly to the Gilsdorf operation. Unteroffizier (Junior NCO) Wilhelm Stetter of 1st Battalion, 915th Grenadier Regiment, manned an observation post covering Bettendorf. Through his binoculars, Stetter saw “eight rubber boats at a bend in the Sauer” and concluded this was no small-scale raid but rather “a genuine attack”.

Later that morning, Stetter observed “a long row of men” in camouflage snow suits nearing his position. “Pointing my assault rifle at the column,” he recollected, “I pulled the trigger; my MP 44 rattled.” Stetter and his fellow grenadiers fought a delaying action at Bettendorf all day, inflicting numerous casualties on the American forces, then surging forward all around them.

Back at the crossing sites, Colonel Starbird’s troops began the task of constructing heavy-duty vehicle bridges. At 0400 hours, Lieutenant George Stejskal and six combat engineers from the 133rd ECB traversed the Sauer near Gilsdorf to lay guide cables for a treadway bridge. German MG42 crews hidden along the riverbank fired on them, wounding one G.I. and scattering the rest. Stejskal led his men to cover, then went back with two volunteers to rescue the injured soldier and treat his wounds.

After some nearby riflemen silenced the enemy guns, Lieutenant Stejskal’s team got back to work. Three and a half hours later, the first treadway bridge at Gilsdorf opened for business. It came at a cost, though—nine members of the 133rd ECB were wounded and three killed by hostile fire that morning.

On the Red Diamond’s western flank, Company C of the 150th ECB erected an 80-foot Bailey Bridge over the Sauer at Ettelbruck. Tank destroyers from A/803 TD then dashed over it to assist the infantry. One 3rd Platoon crew earned mention in the battalion’s after-action report when they poked the barrel of their M10’s main gun through the window of a house in Erpeldange to flush out 27 German prisoners of war without firing a round.

This bridging effort succeeded brilliantly, according to the division’s historian: “The Fifth’s own 7th Engineer Battalion and the Third Army’s [133rd Engineer Battalion,] 150th Engineer Battalion and 509th Treadway Bridge Company threw across one treadway bridge, two Class 40 Bailey bridges, two assault boat and two foot bridges in less than 18 hours, despite the intermittent artillery fire that fell along the river two hours after troops forced the crossing.”

“By nightfall on the 18th,” the division history continued, “the Second and Tenth Regiments had won a bridgehead across the Sauer that was 2,000 yards deep and covered an irregular 8,000 yard front.” Ettelbruck, Erpeldange, Ingeldorf, Gilsdorf, and Bettendorf were all in U.S. hands, while the heavily defended village of Diekirch had been surrounded. The 5th Infantry Division historian went on to claim that “whole platoons of Germans were taken prisoner who claimed they never had a chance to fire a shot.” Officially, 150 grenadiers went into prisoner-of-war cages that day.

Yet the foe demonstrated he still had plenty of fight left in him. At dawn on January 19, marauding German riflemen struck Company A, 2nd Infantry, near the Friedhof Farm north of Erpeldange. Cut off by enemy infiltrators, company commander Captain Lennis Jones singlehandedly killed 11 of them with his pistol and carbine before leading a charge that finally repulsed the grenadiers’ attack. This action earned Jones a Distinguished Service Cross.

Aided by field artillery, 4.2-inch mortars, and five M4 Sherman tanks from A/737 TB, infantrymen of the 2nd CT’s 3rd Battalion finished clearing Diekirch by 1200 hours. There they found evidence of war crimes in the form of several recently executed civilians. At Bastendorf, members of the 2nd Battalion, 10th CT, discovered a number of dead American soldiers left piled up inside the village church. These unfortunates, all members of the 28th “Keystone” Infantry Division, had apparently been captured in the December offensive, then stripped of their shoes and shot in the back of the head.

The Red Diamond’s combat teams continued pressing northward while maintaining constant contact with the 4th and 80th Infantry Divisions advancing on their flanks. It was slow going; hilly terrain, thick snow, and ferocious German resistance made each step a struggle. Land mines and booby traps also took their toll on those G.I.s unlucky enough to trip one. The 150th ECB’s Bruce Reagan testified to this hazard when he recalled a respected lieutenant losing his foot to a Schü mine near Diekirch.

January 20 started as another day of cold rations, no air cover, swirling snow, and freezing cold. Private William H. Thomas, machine gunner with Co. M, 10th CT, was standing guard on a hillside near Tandel when he saw some 30 grenadiers moving into his field of view. The column advanced to within 25 yards of Thomas’ position before its officer spotted him. Both men then spent several minutes in a bizarre pantomime debate, each madly gesturing for the other to surrender before Private Thomas—tiring of this game—fired into the German patrol and wiped it out.

Several miles to the west, another group of grenadiers allowed Co. F of the 2nd CT to get within 100 yards of their strongpoint on the Kippenhof Farm before opening up with well-sited automatic weapons. Grabbing his company radio, Staff Sergeant Clemens G. Noldau crawled forward over bare, exposed terrain to locate the enemy position and transmit a call for artillery support. Although German gunners killed Noldau, his sacrifice, which earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, led to Kippenhof’s capture that afternoon.

By January 21, Generalmajor Bazing’s division could no longer be considered combat capable. One by one his line of infantry strongpoints such as the ones at Friedhof and Kippenhof farms had been crushed by relentless American attacks, while the 352nd VGD’s artillery was of little help, its howitzers and rocket artillery either obliterated by counterbattery fire or unable to shoot due to ammunition shortages.

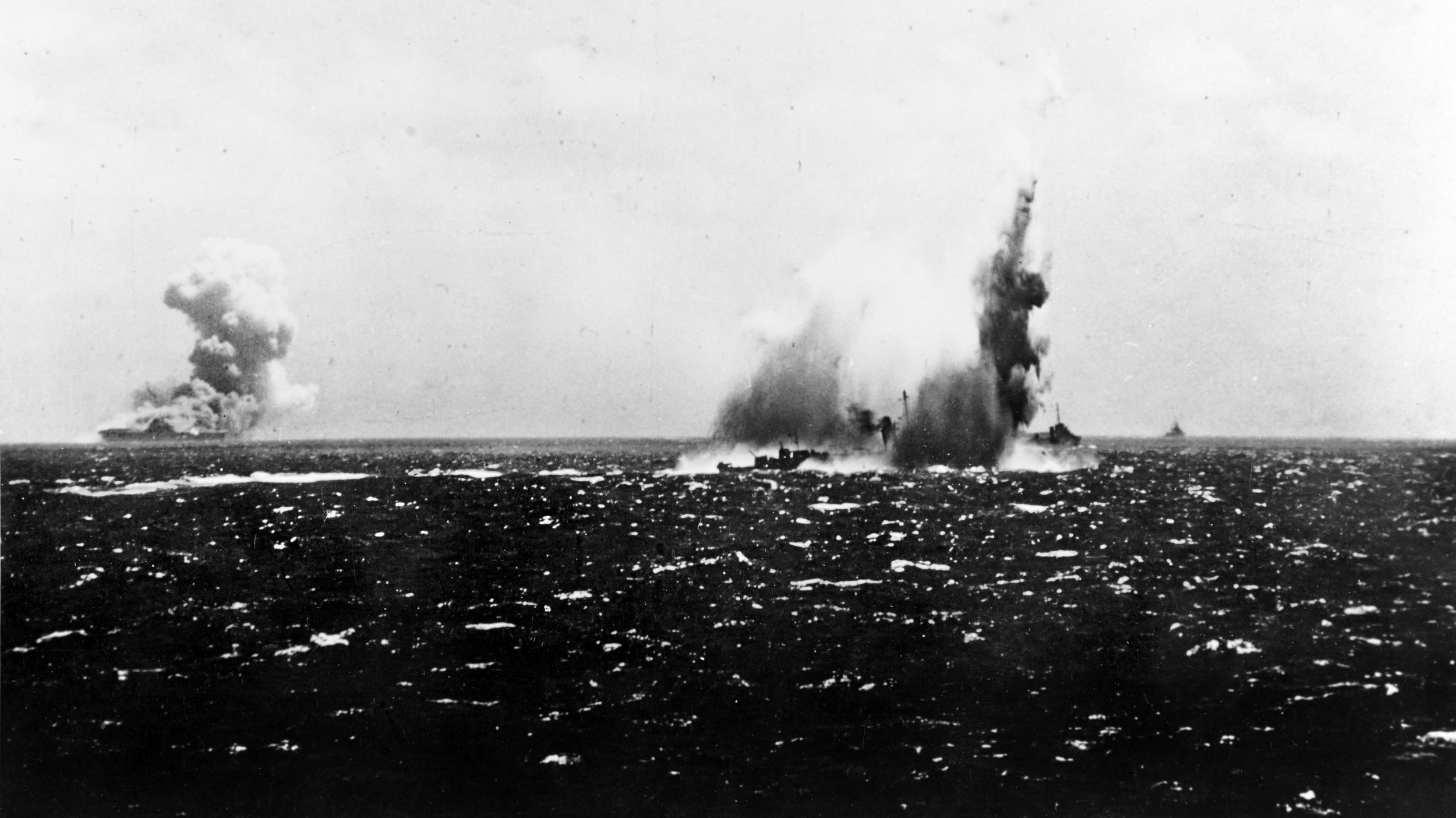

Bazing’s situation caused high command to rush forward reinforcements, as well as to hasten the withdrawal of all Wehrmacht forces still in Luxembourg. Those units needed to reach Vianden and the last bridge under German control that spanned the Our River before American forces wrecked or captured it. Unfortunately for them, the skies cleared just enough for low-flying spotter planes from the 5th Infantry Division’s 46th FAB to discover their march columns. Following close behind were several squadrons of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers belonging to Patton’s XIX Tactical Air Command (TAC).

Red Diamond Division G.I.s got to watch the Thunderbolts at work. “Those Krauts had hundreds of vehicles of all descriptions jammed on those roads bumper to bumper,” one Pfc. remembered, “when that fog lifted and our planes came down on them.” His account continued: “All day the air shook with the violence of our artillery barrages and the concussion of the aerial bombs.” Ultimately, XIX TAC received credit for destroying or damaging 1,700 enemy vehicles that day.

On January 22, the fresh 11th CT relieved an exhausted 2nd CT in the western part of General Irwin’s attack zone. This day also marked the division’s first encounter with German armor—Co. B of the 737th TB tangled with three Mk IV panzers while supporting 10th CT’s push on the Puhl farmstead.

A dangerous new threat was now entering the battlefield. This force, the Panzer Lehr Division, operated a number of Mk V Panther and Mk VI Tiger tanks deemed far superior in firepower and armor protection to the Americans’ M4 Shermans. While far below its authorized strength due to battle losses and mechanical breakdowns, Panzer Lehr still represented an exceptionally formidable foe.

The Red Diamonds had a few tricks of their own, however. For the first time, division artillery was allowed to utilize proximity-fused projectiles that greatly enhanced the effectiveness of its coordinated “time-on-target” fire missions. And the 737th TB now fielded several M4A3E2 assault tanks, which they nicknamed “Jumbos.” Outfitted with an extra inch and a half of armor welded to the turret and hull, these Jumbos could better withstand a hit from German high-velocity tank guns.

On January 22, the 11th CT’s advance on Hoscheid quickly stalled due to unfavorable terrain. Unit historians claimed that “the steep grades, nature of the ground and deep snow proved to be a great obstacle, causing general fatigue among the foot elements and prohibiting movement of vehicles.” A tenacious defense further complicated matters; it took two full days to capture this small village.

The 10th CT spent four days—January 24-28—battering itself against Putscheid, the last urban town in its operational area still held by German forces. Three times 1st Battalion went in with tank and TD support, only to see each attempt blunted by the aggressive, battle-wise Panzer Lehr. On January 28, after a massive bombardment that involved the entire 5th Division Artillery and most of XII Corps’ big guns, 10th CT’s riflemen finally seized what remained of Putscheid. That afternoon they easily defeated a local counterattack, concluding the Red Diamonds’ 11-day winter campaign.

This victory came at a high cost. General Patton himself acknowledged the sacrifice of every American soldier who served along the Sauer that January when he exclaimed, “How human beings could endure this continuous fighting in sub-zero temperatures is still beyond my comprehension!”

Yet there was little respite for those G.I.s who had just helped flatten the Bulge in Luxembourg. After taking five days to rest and reconstitute their ranks, the men of the Red Diamond moved on to an assembly area near Echternach. On February 7, they again leaped the Sauer River, only this time the 5th Infantry Division’s axis of advance faced east toward the Siegfried Line.

No one knew it then, but the war in Europe would end with Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender in just 90 days.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired military officer and historian based in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Sgt. Maj. John Conley (U.S. Army Ret.) for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments