By Richard Rule

By mid-1942, the towering German battleship Tirpitz stood alone as the largest, most powerful warship in the world. Despite rarely venturing from her lair deep within the Norwegian fjords, her mere presence in the region forced the British Royal Navy to keep a large number of capital ships in home waters to watch over Allied convoy routes to the Soviet Union.

The fact that the menacing shadow of one ship could hold so many others virtually captive in the North Atlantic at a time when they were desperately needed elsewhere was an intolerable situation in the eyes of Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. “The greatest single act to restore the balance of naval power would be the destruction or even crippling of the Tirpitz,” he wrote. “No other target is comparable to it.” His obsession with the massive dreadnought was the driving force behind numerous Royal Air Force and Royal Navy attempts to sink her, but all had met with failure.

The harsh reality was that inside Norwegian waters the Tirpitz enjoyed the protection of an ice-clad fortress bounded by sheer walls of solid rock and enhanced by German ingenuity. The natural defenses had been substantially bolstered by the deployment of countless artillery batteries and antiaircraft guns in the surrounding mountains while close-quarter protection for the 42,000-ton battleship was provided by layers of heavy antitorpedo nets that were closed around her like a second skin. Nothing had been left to chance, and within these all-encompassing defenses, the Germans confidently believed the “Lonely Queen of the North,” as the Tirpitz was known, was untouchable. To the Royal Navy looking on from afar, it was not an idle boast.

Churchill wanted action, but the British Admiralty could see no way to strike at its nemesis. Naval bombardment was impossible due to the configuration of the intervening land, the fjords were mostly beyond the range of land-based bombers, and a raid by conventional submarines would be suicidal.

The X-Craft Program

However, from within the deepening gloom that beset the Royal Navy, a ray of light emerged. For a number of years, Navy engineers had been working on the prototype for a 51-foot, 30-ton, four-man midget submarine specifically designed to attack naval targets in strongly defended anchorages. They had developed, in effect, a complete submarine in miniature, but in lieu of torpedoes, the midgets were fitted with two crescent-shaped detachable explosive charges fitted externally on either side of the pressure hull. These mines, each containing two tons of Amatex explosive, were to be planted on the seabed directly under the target ship then detonated with a variable time fuse.

It was deemed unlikely that the German command ever envisaged a raid by midget submarines or X-craft, as the British vessels were known, giving rise to optimism that at last an attack on the Tirpitz might stand a fighting chance of success. It was a tantalizing prospect.

Winston Churchill, a renowned enthusiast of covert operations, had been greatly impressed by an earlier raid launched by Italian divers against British ships in Alexandria harbor and was eager for the X-craft to replicate a similar feat against the Tirpitz. His impatience to strike, however, was tempered by a Royal Navy that would not be rushed. While operational considerations dictated that these vessels would require many unique features, Navy experts were determined to develop the X-craft prototype along principles firmly grounded in reality and based on sound submarine practice. Within the halls of the Admiralty there was little enthusiasm for the unconventional, outlandish approach typical of the Special Operations branch.

Even at this early stage of X-craft development, the sheer volume of pipes, dials, gauges, levers, and other vital equipment crammed inside the tiny hull left very little space for crew comfort. Navy planners recognized only that men possessing extraordinary self-control could cope with the claustrophobic conditions, and they sought volunteers “for special and hazardous duty” from among newly commissioned Royal Navy officers. The candidates, including many from Australia and South Africa, were not told what the mission entailed, but over the next few months, they were filtered through rigorous selection criteria. The physically unsuitable, the timid, or men with a “death or glory” outlook were steadily weeded out. Those who made the grade quickly found themselves undergoing intense training and theoretical courses on the X-craft.

Training and weapon development proceeded simultaneously, as further modifications, tests, and sea trials were conducted until the final construction design was approved. With the aid of civilian firms, the first six vessels, designated X-5 through X-10, rolled off the line to form the fledgling 12th Submarine Flotilla.

The Plan to Sink the Tirpitz

As the momentum of the operation gathered speed, bold theory predictably collided head-on with practical application. Before any attack could be launched, a number of significant roadblocks would need to be cleared, not the least of which involved getting the X-craft to Norway. Experts agreed that German patrols and air reconnaissance ruled out launching the vessels from a depot ship near the Norwegian coast, and a weeklong journey across the North Sea was considered beyond the endurance of the four-man crew. They would be completely exhausted before they ever reached the target. It was a vexing problem, but after much deliberation it was decided that the midgets would be towed to the operational area behind patrol submarines using 200-yard manila or nylon cables.

Even under tow, however, the 1,200-mile journey would still take eight days, so “passage crews” would be trained to ferry the craft to the target area. Then these men would be swapped with the “operational crews” who would make the voyage in the towing submarines.

These transit crews would play a vital, yet largely unsung role in the operation. Theirs would be an exacting, demanding duty in which they were to remain virtually submerged throughout the entire journey, only coming to the surface every six hours for 15 minutes to ventilate their hulls. It promised to be a voyage of incredible hardship, and few envied them.

Another critical factor in the planning was the timing of the raid. By early 1943, the Norwegian Battle Group of Tirpitz, the battlecruiser Scharnhorst, and the pocket battleship Lutzow had relocated to new berths within the small landlocked basin of Kaafjord, northern Norway. The German ships were now anchored five degrees north of the Arctic Circle where there was no darkness in summer and no light in winter.

Summer was unsuitable for a British attack because the X-craft needed the cover of darkness to recharge their batteries; winter deprived them of daylight to make visual contact with the target. The most favorable times for an attack occurred during the two occasions each year when daylight and darkness were equal, the equinoxes in March and late September. March was too soon, so the Admiralty settled on late September with the attack to go in on September 22. Navy planners had been swayed by intelligence reports from Norwegian agents indicating that on this date the Tirpitz’s 15-inch guns would be stripped and cleaned, and her sound detection equipment would be down for routine servicing.

Operation Source

In June 1943, specialized training for what came to be called Operation Source started in earnest when men and machines moved to the secret wartime base known as Port HHZ in Loch Cairnbawn, northern Scotland. Amid tight security, the Navy had designed a course that replicated the fjord up which the men would travel to attack the Tirpitz and her escorts, Scharnhorst and Lutzow. Now putting their new X-craft through trials, the men vying for selection carried out simulated attacks, rehearsed towing procedures behind larger submarines, and perfected techniques for cutting through antisubmarine nets. The men grew accustomed to the squalid, cramped interior of the vessels, but they never learned to enjoy it.

Throughout their arduous training, the strengths and weaknesses of the volunteers were constantly evaluated; everything they did and said during these interminable months played a role in determining who would go and who would be left behind. If the mission were to stand any chance of succeeding, the personnel conducting it would need to be the very best, both mentally and physically. The Navy recognized that a midget submarine would get the men to within striking distance of the Tirpitz, but it would take cold-blooded courage and fierce determination to breach the defenses and sink her.

Finally, after nearly 18 months of training, planning, and construction, Operation Source was ready for the ultimate test. The crews had been finalized, and among those selected was a 26-year-old Scotsman, Lieutenant Duncan Cameron, Royal Naval Reserve, whose natural leadership qualities and stout character saw him awarded the command of X-6. Another successful candidate was a 22-year-old veteran of the submarine service, Lieutenant Godfrey Place RN DSC, who took command of X-7. These remarkable men were destined to play pivotal roles in what was to be one of the most daring exploits of the entire war.

An Experimental Mission

The Admiralty’s operational plan called for each pair of submarines to make their way independently to a position west of the Shetland Islands. From this point, they would sail on parallel courses approximately 20 miles apart to the jumping-off point at Soroy Sound, some 11 miles off the Norwegian coast and almost 100 miles from Kaafjord.

From this location, the X-craft would negotiate their way independently up Altafjord via Sternsund, cut their way through the nets at the entrance to Kaafjord, and then slip under the enclosures surrounding each of the ships to lay their charges. X-5, X-6, and X-7 would strike at the Tirpitz; X-8 at the Lutzow; and X-9 and X-10 at the Scharnhorst. It was an extraordinary undertaking, but these were extraordinary times and the stakes were high.

Shrouded in secrecy, the boats sailed from Loch Cairnbawn behind their parent submarines on the night of September 11-12, 1943. Ahead lay 1,200 long, gray sea miles to Norway. As a select few watched the motley fleet disappear into the gathering darkness they knew that nothing like this had ever been attempted before. They wondered how many, if any, would make it home.

Operation Source was, in so many ways, an experimental undertaking. There had been little practical experience to draw upon, and planning staff anticipated the likelihood of mishaps en route—they seemed inevitable.

One of the many unknowns involved the reliability of the manila towlines. Nylon was the superior material, but only three were available in time for the mission, and it was hoped that the manila lines would work—but nobody knew for sure. As events transpired, the doubts surrounding their suitability would soon be tragically borne out.

A Hazardous Journey to the Target

After four uneventful days of passage, the weather began to rapidly deteriorate on September 15. As the larger vessels pounded through the mounting seas, life for the passage crews soon became unbearable. Wretched with debilitating seasickness, the men could neither stand properly nor lie down comfortably as they wrestled around the clock with their charges, which, on the end of their towlines, where being tossed and pitched about like kites in a storm.

The stress loads on the cables increased dramatically as the vessels surged as much as 100 feet through the water, and eventually the manila lines to X-8 and X-7 succumbed to the strain and parted. The passage crews in both the X-craft realized almost immediately what had happened and surfaced. It was no easy task to bring them both back under tow with auxiliary lines, and many hours were lost before the journey could continue. The troubles for X-8, however, were far from over as a water leak in the starboard mine gave the vessel a pronounced list.

The crew struggled hard to maintain control, but it soon became clear that they would need to jettison the charge and continue with only one. The faulty explosive was put on “safe” and released to the depths, but a short time later the port mine also developed a leak. With little alternative, it too had to be jettisoned. It exploded prematurely, causing substantial shock damage to the submarine’s internal systems.

With the battered X-8 now unable to dive and close to foundering, the decision was made to scuttle her. The manila tows soon claimed another casualty when the cable to X-9 suddenly snapped. Unlike the previous line failures, this break occurred near the mother ship leaving the full weight of the waterlogged towline hanging off X-9’s nose. Already trimmed bow heavy to counteract the upward pull of the parent vessel, X-9 dived out of control to the bottom of the North Sea, taking her transit crew with her.

Not only defective equipment threatened to derail the mission. At 0105 on the morning of September 20, Lieutenant Place, who was now aboard X-7, brought the vessel up to ventilate. The towing submarine had also surfaced to find itself on a collision course with a drifting mine. Following evasive action, the crew watched the mine pass by only to see their wake drag the mine’s mooring line onto the tow cable to X-7. In a few seconds, the lethal charge slid down the hawser and wedged itself in the bow of the X-craft where it bounced up and down with the pitching seas.

Lieutenant Place immediately scrambled along the deck casing and, as the wind and spray tore at his clothes, calmly untangled the mooring line from the bow, then deftly kicked the mine clear with his boot. The unwelcome stowaway soon disappeared from view and the voyage resumed.

Mechanical Failures and Leaks in the X-Craft

By approximately 1800 on September 20, the four remaining X-craft had finally made their landfalls seaward of Soroy Sound as scheduled. Last minute reconnaissance over the target area, however, indicated that neither the Scharnhorst nor Lutzow were in their berths. With X-8 and X-9 already lost, the Admiralty decided that the four remaining submarines were to attack the Tirpitz. By 2000, the X-craft had successfully slipped their tows and set a course for the declared minefield at the entrance to Sternsund. There was no turning back now; they were on their own.

With X-6 running on the surface, Lieutenant Cameron took up lookout duty on deck as his craft steadily motored through the short arctic night toward the coast. Skirting the outer rim of the minefield, X-6 passed safely through the first of many obstacles, and soon Cameron could make out the rugged peaks towering on either side of the entrance to Stjernsund, a narrow passage of water leading to Altafjord. The mouth of Stjernsund was protected by shore batteries and torpedo tubes, and with the onset of dawn Cameron submerged to 60 feet and quickly slipped through with the incoming tide. He waited until he was about a mile inside the fjord then cautiously brought X-6 up to periscope depth and scanned the glassy water for any signs of trouble.

It was such a beautifully tranquil place that it was hard to believe that violent death could be only a matter of moments away; it was a sobering thought, and Cameron dived and continued his journey concealed in the gloom of the shaded northern shore. So far, everything had gone smoothly, but they all knew the real test was yet to come.

The other three X-craft had also passed through the entrance at Stjernsund without difficulty, but water seeping into X-10 caused an electrical short circuit that disabled both her periscope and gyrocompass. Despite valiant efforts to repair the defects, the bitterly disappointed crew realized that, with their craft hopelessly crippled, they were out of the running. To avoid compromising the mission, they would spend the daylight hours of September 22 on the bottom before eventually retracing their steps out of the fjord.

The original attacking force of six had now been whittled down to just three, and there were still many hard miles to travel. The crew of X-6 expected to reach the inner end of the waterway near Altaford by last light and planned to spend the night among the Bratholme group of islands to recharge the batteries and prepare for the attack the following morning, September 22.

They were making good progress, and despite the rigors of the 1,200-mile journey, X-6 had been handed over in near faultless condition. But, as the day progressed, things started to go awry. A water leak in one of the side charges had steadily worsened, giving the vessel a severe list to starboard, and her automatic helmsmen had broken down, but of most concern was her periscope lens, which had begun to continually flood. The leak was discovered to be outside the hull and unrepairable. The periscope would therefore have to be tediously stripped down and emptied of water after nearly every use.

In isolation, the mechanical failures did not present insurmountable problems, but a reliable periscope was essential for Cameron to safely conn the craft up the fjord. Its slender shape had been specially designed to minimize water disturbance, but such a feature counted for nothing if he could not see anything through it. When the action started the following day, he prayed that it would not let him down.

Sitting in Enemy Waters

With the onset of darkness, X-6 maneuvered into a small, desolate brushwood cove, and while his crew was below preparing for the trials ahead, Cameron climbed out on the deck casing to look around. In the distance, he could see the lights of the large German destroyer base at Lieffsbotun and the town of Alta beyond, but secreted away in their small hideaway it was dark, bitterly cold, and silent—or so he thought. Suddenly, not more than 30 yards away, the door to a cabin burst open, bathing the area in bright light. Cameron froze, barely able to breathe, as male voices trailed out over the water.

Were they German?

Within a few seconds, the door was closed and Cameron was once again swallowed up in the darkness. Quickly recovering from the shock, he decided to find somewhere else to lay up for the night. However, upon leaving the small harbor, X-6 was nearly run down by a fishing boat only to then narrowly avoid another vessel coming from the opposite direction. It was a nerve-wracking experience, and Cameron ensured that their next stopping place was remote and uninhabited.

While keeping watch topside in the still arctic night, he reflected on what had been a very eventful 24 hours. It was both surreal and exhilarating to realize that in the midst of the most destructive war the world had ever known, four Royal Navy seamen could actually be sitting squirreled away deep inside an enemy fleet anchorage listening to the BBC and drinking cocoa. The wonder of the moment was shattered at 2100 when a volley of star shells and searchlights erupted from the destroyer base across the water.

Had the Germans detected one of their comrades? They waited anxiously for something to happen, but to their relief no alarms were sounded, no engines were heard to start, and soon all was quiet again. Cameron had no idea what the commotion had been about, but he did know that he would be happier once they were on their way.

Duncan Cameron’s Bold Maneuver

At 0130 on the morning of September 22, Cameron went over his attack orders once more, then destroyed them. Prior to leaving Scotland, the X-craft commanders had taken precautionary measures to avoid blowing each other up by agreeing to drop their cargoes between 0500 and 0800 with charges set to explode between 0800 and 0900. Cameron planned to unload his bombs at 0630, then retreat out of the fjord, but when he tried to preset the timers he found the fuses on the port side explosive continually shorted out. There was no way of knowing when it would explode.

By now the mechanical attrition was sapping the crew’s confidence, but the young officer was determined to press on. With little discussion, he gave his orders, and at 0145 they set a course for the Tirpitz. The final stage of the attack was underway.

The nets covering the mouth of Kaafjord were 158 feet deep and included a 437-yard-wide boom gate fitted near the shallow southern shore. By 0400, X-6 had maneuvered to within half a mile of these formidable defenses, and her diver was suiting up in readiness to cut a hole through the antisubmarine netting. As they closed to within 30 feet of the mesh, the sound of propellers became audible overhead as a Norwegian trawler headed for the boom gate.

Cameron realized it must have been open and without hesitation brought X-6 to the surface. The crew could scarcely believe what he was going to do as he maneuvered into the wake of the coaster and with incredible audacity proceeded through the gate in broad daylight. It was a torturous passage as they waited for an alarm to be sounded, but, incredibly, they made it through without detection and immediately dived.

They could hardly fathom their luck. Perhaps in the choppy water the Germans mistook the low silhouette of the X-craft for a towed barge or raft. In any case, Cameron’s bold maneuver had paid off and by guess and by God the small submarine began groping its way up the fjord toward the Tirpitz, which was now only three miles away.

Fire on the X-6

Through the faulty periscope, Cameron spied a waterway crammed with German warships of every size, and it was chilling to realize that to reach the Tirpitz he would have to slip right through the middle of them. A tanker sitting at anchor refueling two destroyers lay directly between X-6 and the Tirpitz, and by dead reckoning he set a course that would, in approximately two hours, take them past the tanker’s stern. It was always going to be a harrowing journey, but the source of most anxiety for the crew arose from the noise generated by the submarine’s trim pumps. They would have to remain in constant use to maintain the craft’s buoyancy in the differing water density, but the sound they emitted was precisely what a hydrophone operator would be listening for.

Progress up the fjord was agonizingly slow, but after two hours Cameron expected to be somewhere near the tanker’s stern and returned to periscope depth to steal a quick look. The hazy image in the lens was enough to send him reeling back in horror; X-6 had surfaced midway between the bow of a destroyer and her mooring buoy. He immediately crash dived to 60 feet, the crew shut down the craft, and they waited. How could they not have been seen or detected by a listening post? These lengthy spells of inactivity punctuated by moments of sheer terror were as taxing on a man’s strength as a grueling marathon, but as the minutes ticked by with no German response, Cameron cautiously pressed on again.

By 0700, X-6 had come within reach of the battleship’s antitorpedo netting, but since passing into Kaafjord the submarine had begun to labor severely. She was in fact barely seaworthy. Cameron once again had to come up to periscope depth to gain his bearings. It was an incredible risk in such a small waterway, but at this vital stage it would have been impossible to navigate their way to the Tirpitz by guesswork alone. Through the faulty lens, he could make out the ship, but as he began scanning the water around her, the periscope motor burned out, filling the submarine with choking smoke

As X-6 submerged to contain the fire, Cameron sensed the despondencyof the men. They had given their all in unimaginable discomfort for 35 hours straight, but faulty workmanship and defective equipment were undermining their every move. However, the predetermined attack period was fast approaching. Time was now critical.

Inside the stifling hot control compartment, heavy with fumes and condensation, stony faces with bloodshot eyes stared at one another in the gloom. They were clearly showing the strain, but nobody could bring themselves to say what they all were thinking. They had no idea how the other X-craft had fared, but if the mechanical defects of X-6 were any indication, they had to assume they were the only ones who had made it this far.

Spotted by the Tirpitz

Little was said, but clearly no one wanted to admit defeat 46 yards from the ship they had come to destroy; an opportunity like this might never come again. The decision was made to press on, but the crew had no illusions about its chances. Even if they remained undetected, X-6 was in no condition to make good an escape. None of them expected to be leaving Kaafjord.

Hugging the north shore, X-6 dived to pass under the nets, which were believed to have been no deeper than 60 feet. But after several attempts at various depths, it was realized that the mesh went all the way to the bottom. The Admiralty intelligence was wrong, and now, at this critical moment, there was no way through. The latest setback came as a body blow, but Cameron, dizzy with fatigue, would not let the mission end like this. His blood was now boiling, and he was determined to find another way in. He brought the vessel to periscope depth once again to check the boat gate located close to the shore and spied a picket launch about to pass through.

With a reckless disregard for the danger, Cameron surfaced into the wash of the small boat. The ploy had succeeded at the entrance to Kaafjord, and maybe it would work again. Quickly juggling the pump controls, the crewmen motored through the gate in broad daylight right behind the picket boat, bumping and scraping the bottom as they did. Surely, this time their boldness would be their undoing, but, remarkably, they made it through unnoticed. As the boom gate closed behind them, Cameron took X-6 down into deeper water and set a course that would take them under the stern of the Tirpitz.

Like silent assassins sliding through the shadows, they inched their way through the frigid waters to within striking distance of their target. Suddenly the X-6 ran aground and momentarily broke the surface less than 200 yards from the battleship. The disturbance was seen by a lookout, but British luck continued to hold when the sighting was dismissed as being merely a porpoise and no alert was raised. The German sailors on Tirpitz had endured many false alarms over the years and now avoided instigating them for fear of ridicule.

Inevitably, though, Cameron’s run of luck finally ended a few minutes later when X-6 careered into a submerged rock that wrecked the gyrocompass and thrust the vessel to the surface 80 yards abeam of the ship. There was no mistaking what she was this time, but the sighting of X-6 caused considerable confusion aboard the Tirpitz. An incorrect alarm sent men scurrying to secure watertight doors instead of their action stations, and vital minutes were lost before the correct submarine alert was sounded. Even then, few senior officers believed a submarine could have gotten through. The X-craft was too close for the ship’s big guns to depress sufficiently to engage her, so crewmembers opened fire with small arms and threw grenades.

Now the crew of X-6 knew that the Germans were aware of their presence. They no longer had to worry about what might happen; it was now a matter of completing their mission before it did happen. Being in the line of fire threw off the fatigue that had enveloped Cameron’s men and rekindled their determination to hit back. They too had powerful weapons, and they were now intent on using them.

Placing the Charges

As bullets churned up the water around the vessel, Cameron quickly dived, but with the periscope now almost completely inoperable and the gyrocompass out of action, he had no idea which way he was heading. Oblivious to the chaos unfolding above him, he blindly groped his way toward what looked like the shadow of the ship but fouled a wire hanging over the side and was stuck fast. After desperate maneuvering, the submarine broke free of the snag only to shoot to the surface again close to the port bow. Undaunted by the hail of bullets once again striking the hull, Cameron took the submarine down and backed her under the Tirpitz where he quickly released the charges beside B Turret.

With no hope of escape, the exhausted crew destroyed its secret documents and equipment. As the sailors brought X-6 to the surface to surrender, Cameron ordered her sea cocks opened and her motor left running full astern with the hydroplanes to dive. As they opened the hatch, the firing immediately stopped and the men scrambled onto the deck. A launch from the ship was soon alongside to pick them up, and a German officer tried to secure a tow to the X-craft but the line was hastily cut as the submarine began to sink, almost taking the launch down with her.

The four prisoners were taken to the ship, and to the surprise of the Germans, smartly saluted the colors as they stepped onto the deck. Under guard, they stood huddled together looking bedraggled and physically spent, wondering what the future held for them as the minutes ticked by. On the express orders of the Tirpitz’s commander, Captain Hans Meyer, the men were immediately given coffee and schnapps.

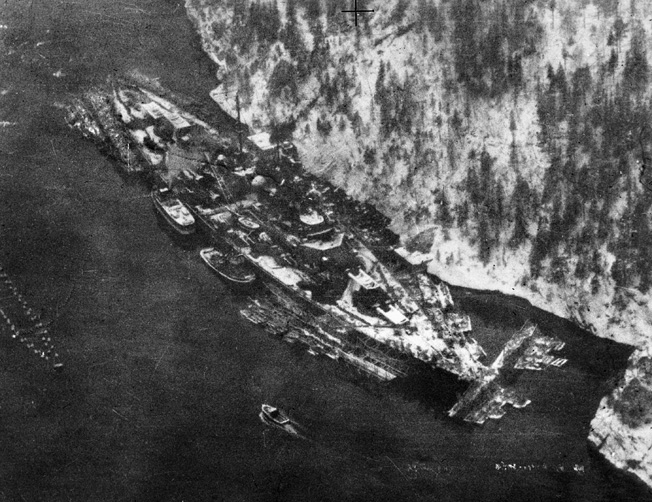

battleship is apparent in this photograph.

Meanwhile, at almost the same instant Cameron and his crew were scuttling their vessel, Lieutenant Place in X-7 was sitting astern of the Tirpitz, preparing to offload his deadly cargo. Earlier in the morning, he had literally climbed over the nets at Kaafjord but had soon become entangled in the netting around Lutzow’s empty birth. After struggling desperately for an hour, Place finally broke free only to become entangled in Tirpitz’s netting. The violent effort undertaken to break loose had damaged his gyrocompass, and the craft broke the surface at 0710.

With the Germans at that moment occupied with X-6, Place was not seen. Diving once again, Place, like Cameron before him, found that the nets went all the way to the bottom, but without realizing it he had fortuitously slipped through an opening on the seabed. By this time he had completely lost his bearings and had come up to periscope depth to discover the Tirpitz only 98 feet away. He immediately submerged and made his run to the target at a depth of 40 feet.

Hitting the ship on the port side, the X-7 slipped under her keel. At this point, Place could hear the detonation of grenades around Cameron’s X-6 but assumed they were meant for him. Sidling along the hull, he placed one charge beneath the bridge and the other near the stern under the aft turrets. Each was set to explode in approximately one hour’s time.

It was now 0720, and Place attempted to escape, but without a compass he would have to guess his way back to the opening on the seabed. Sliding over the top of the first net, he was spotted by the Germans but disappeared from view. After an hour trying to find the opening, he only succeeded in getting himself entangled again. This time he was stuck fast, fully realizing he was about to be destroyed by his own charges.

Explosions Under the Tirpitz

Aboard the Tirpitz, the Germans had at first refused to accept that Cameron and his crew were British. They suspected them of being Russians and were unwilling to believe they could possibly have come all the way from England to Kaafjord in such a small submarine. Passing crewmembers mocked the prisoners for not having used their torpedoes when they had the chance, but Captain Meyer, who had been studying his captives from the bridge, had grown suspicious. Privately, he greatly admired their courage and daring, but in his mind, they lacked the demeanor of men who had failed.

Meyer was soon convinced that they had not been armed with torpedoes but had instead used mines either on the ship or on the seabed. Divers were immediately ordered over the side to check the hull, and attempts were made to move the ship by heaving on the starboard cable and veering on her port to swing the bows away from the likely position of the charges. Meyer had earlier considered taking the ship into the deeper water beyond its enclosure, but the sighting of X-7 outside the nets changed his mind. In any case, it would have taken over an hour to get the ship underway.

The prospect of another submarine loose in Kaafjord had caused absolute pandemonium. Cameron and his men had also seen X-7 slide over the top of the nets earlier and had noticed that her mine clamps were empty. As guards herded them below, they could not let on that with eight tons of explosives beneath the ship, this was the last place they wanted to be!

A short time later, at 0812, a series of colossal explosions violently heaved Tirpitz’s stern six feet out of the water. A German sailor who had also served on the Scharnhorst recalled the moment. “We’ve had torpedo hits, we’ve had bomb hits. We hit two mines in the channel, but there’s never been an explosion like that.” Lights failed, equipment was strewn in every direction, and men were hurled through the air like rag dolls. The four prisoners were dragged back onto the deck to be confronted with utter chaos and panic.

“The German gun-crew(s),” one British sailor later recalled, “shot up a number of their own tankers and small boats and also wiped out a gun position inboard with uncontrolled fire.” Orders were issued, then countermanded, as officers tried to regain control of the men who were running in all directions. With tensions running high, the mood of the Germans had turned very ugly, and the British seamen were lined up against a bulkhead where an outraged officer, brandishing his pistol, demanded to know how many more submarines there were.

When they refused to answer, Cameron was convinced they were about to be shot. It was not until Admiral Oskar Kummetz, the senior naval officer in the region, came aboard to find out what had happened that the situation was defused. He stopped on his way to the bridge, looked over the four bedraggled Englishmen, then curtly told his subordinate to put the pistol away.

Trapped in the X-7

Below the water’s surface, meanwhile, X-7, instead of being destroyed by the explosion, had been wrenched clear of the netting. Place took her to the bottom to assess the damage but quickly realized that although the pressure hull was intact much of X-7’s mechanical controls and internal systems were beyond repair.

Place tried to bring her up again but found X-7 was almost uncontrollable as she repeatedly broke the surface and was hit by gunfire from the Tirpitz. With little prospect of escape, Place decided to abandon ship, but he did not expect a warm reception.

Surfacing near a moored gunnery target, the small submarine was immediately raked by intense small-arms fire. Place gingerly opened the fore hatch and began waving a white sweater, signaling his intention to surrender, and the firing stopped. As he leaped into the water and swam to the gunnery target, X-7 dipped her bow, allowing water to pour through the open hatch. The vessel quickly sank beneath the surface with three crew members trapped inside. One managed to escape later, but tragically, the other two drowned. Their bodies were later recovered by the Germans and reportedly buried with full military honors.

The two survivors of X-7 joined their comrades aboard the Tirpitz but were bitterly disappointed see her still afloat. Following their transfer to the naval prisoner of war camp at Marlag-O, near Bremen, Germany, Cameron and Place, unaware of the damage they had caused, would spend a great deal of time discussing what they could have done to improve the outcome. On the other side of the Atlantic in London, Norwegian agents and Énigma decrypts provided detailed reports on the status of the wounded battleship, and Churchill was delighted.

Tirpitz Out of Operation

Although Tirpitz had not been eliminated, it was clear that she would be out of action for at least six months. Her four main turrets had been thrown from their roller-bearing mountings, her hull gashed and distorted, all three engines were inoperable, and the port rudder and all three propeller shafts were out of action. Five hundred tons of water had poured into her hull and, although her water integrity held, a number of hull frames were damaged beyond repair. She would in fact remain laid up in Kaafjord until April 1944 and was never to regain complete operational efficiency.

So ended the first attack by British midget submarines and the first successful blow against the mighty Tirpitz, but it had come at a cost. All six craft were lost along with nine men killed and six taken prisoner. For their roles in this remarkable operation, described by Rear Admiral C. B. Barry, DSO, as “one of the most courageous acts of all time,” both Lieutenant Cameron and Lieutenant Place were awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military decoration.

Both men remained in the Royal Navy after the war, and Duncan Cameron attained the rank of commander before suddenly dying on active duty in April 1961. He was 44 years old. Godfrey Place retired a rear admiral in 1971 and died peacefully in 1994 at the age of 73.

Mystery still surrounds the fate of X-5, commanded by Lieutenant H. Henty-Creer. His vessel was sighted near Kaafjord after the explosion, at 0843, but was raked with heavy fire from Tirpitz and claimed as sunk with all hands. Authorities believed that she had perhaps missed the first specified attack period and laid up in the fjord to plant her charges to follow the initial attack, then make her escape.

There are many, however, including the young officer’s family, who believe that Henty-Creer and his crew had in fact planted their charges before being sunk. They speculate that the sheer force of the detonation beneath the stern of the Tirpitz indicated the presence of considerably more explosive than was deposited by X-6 and X-7 and that the 21-year-old Henty-Creer should have been awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously for his role. The controversy, which has continued since 1945, was reignited in 2003 when local Norwegian divers discovered what appears to be the wreck of X-5 in Kaafjord—minus her charges. Were they planted beneath the ship in 1943? Investigators are continuing the search for answers.

The fate of the Tirpitz, however, is not in dispute. Her ill-starred career came to an abrupt end in Tromso Fjord on November 12, 1944, when she was attacked by stripped-down British Avro Lancaster bombers using the new 13,000-pound “Tallboy” bombs. A direct hit triggered a massive explosion in one of her magazines, capsizing the ship and killing over 900 officers and men.

After the war, the wreck of what had once been the most powerful battleship in the world was declared the property of the Norwegian government and ingloriously cut up for scrap between 1948 and 1957.

Your article is wrong. The TIRPITZ was not the single, largest most powerful warship in the world in mid-1942. Japan had the two biggest battleships ever built, Yamato and Musashi, both weighing about 72,000 tons and both having 9–18 inch guns. The United States had several North Carolina and South Dakota class battleships with 16-inch guns with the latest radar and automatic finding direction on their guns. Tirpitz’s eight 15-inch guns ranked her below eight battleships with nine 16-inch guns (Nelson, Rodney, Washington, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Indiana, South Dakota, and Alabama), five battleships with eight 16-inch guns (Mutsu, Nagato, Maryland, Colorado, and West Virginia, although West Virginia was still being repaired from Pearl Harbor damage in mid-1942).

If anyone’s interested, there is a fictionalized movie about this mission, “Submarine X-1”.

Not a great movie, but enough to give anyone with claustrophobia (like me) the creeps.