By Roy Morris, Jr.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the nation’s most famous writer, a man who had built his reputation on gritty and intense novels about wars, soldiers, and “grace under pressure,” was nowhere to be seen—at least not on the home front.

Ernest Hemingway, coasting on the reputation and earnings of his best-selling 1940 novel about the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls, was off living the high life on his hillside farm outside Havana, Cuba. With his third wife, journalist Martha Gellhorn, he enjoyed a never-ending round of hard-partying visitors and a feral menagerie of un-housebroken cats, one of whom he had taught to drink whiskey and milk with him on mornings after a long night of carousing.

In some ways, Hemingway had already foreseen the beginning of the war in For Whom the Bell Tolls. Like other supporters of the doomed Loyalist government of Spain, he had considered that country’s exceedingly vicious civil war the first battle of World War II, a struggle between the heavily armed troops of fascist general Francisco Franco and the poorly equipped but highly motivated forces of the country’s socialist government.

The fact that German pilots from Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler’s regime had taken part in the fighting, including the terror bombing of the Spanish village of Guernica immortalized in Pablo Picasso’s famous painting of the same name, only underscored the feeling that Spain represented the front line in what would become a decade-long struggle between good and evil.

But unlike the novel’s hero, Robert Jordan, an American fighting with the Loyalists who willingly goes to his death in defense of freedom, reasoning that “if we win here we will win everywhere,” Hemingway himself felt no immediate responsibility to observe—much less participate in—World War II. When his ambitious, excitement-loving wife sought to persuade him to join her as a war correspondent in England, the author observed dismissively that “there would be plenty of wars to go to for a long time, and … there was no special hurry.” (Intentionally or not, Hemingway was quoting himself. In his World War I novel A Farewell to Arms, his wounded protagonist, Frederic Henry, muses that “the world … kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure that it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.”) His second son, Patrick, ascribed his father’s curious disinterest in the war to a less lofty philosophical reason: “He felt that he was entitled to stay behind, living in a place that he liked, and enjoying himself.”

Despite his lack of immediate interest in the conflict, Hemingway was too much a congenital adventurer to remain completely disengaged in the war effort, and in May 1942 he approached the American ambassador to Cuba, Spruille Braden, with an intriguing if somewhat offbeat proposal. Having lived in Cuba for the past three years, after more than a decade spent fishing its turquoise-green waters, Hemingway offered to organize a private network of spies to monitor the large pro-Nazi community of Spanish expatriates living on the island.

Hemmingway the Spy?

Hemingway claimed, with some exaggeration, to have run a similar intelligence-gathering network in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. Braden, a Yale-educated patrician from the author’s old hunting grounds around Elkhorn, Mont., readily agreed, and Hemingway quickly put together an eclectic team of six full-time operatives and 20 undercover agents recruited from his wide-ranging contacts in the Havana demimonde. Among the spies in Hemingway’s so-called Crook Factory were professional jai-alai players, waiters from the author’s favorite watering holes, fishermen, prostitutes, exiled aristocrats, wharf rats, beach bums, and even an activist Catholic priest who had served as a machine gunner in the Spanish Civil War. Reports were funneled through the guest house at Hemingway’s farm, Finca Vigia, and were hand delivered by the writer to the American Embassy on a weekly basis.

Later that same month, Hemingway made a second proposal to the ambassador. In return for a supply of government-issued bazookas, hand grenades, .50-caliber machine guns, and sophisticated radio equipment, he would convert his much-loved fishing cruiser, the Pilar, into a seagoing Crook Factory, cruising the deep waters along Cuba’s northern coast in search of the German U-boats that were then wreaking havoc on Allied shipping in the Caribbean. (In August and September of that year, Nazi subs would sink 71 vessels in 61 days.)

Again, Braden agreed to underwrite the author’s unconventional scheme, and Hemingway, much like Theodore Roosevelt assembling his Rough Riders for duty in the Spanish-American War, put together an elite team of Nazi-hunters, including millionaire playboy Winston Guest, godson of no less a personage than Winston Churchill; champion Cuban jai-alai player Francisco Paxtchi Ibarlucia; Pilar first mate Gregorio Fuentes, one of several rumored models for Hemingway’s later novella, The Old Man and the Sea; Basque fisherman Juan Dunabeitia, whose lifelong knowledge of the sea earned him the nickname “Sinbad the Sailor”; and assorted other Havana hangers-on, including a shadowy American soldier of fortune known only as Lucas. Lending the enterprise a much-needed patina of military professionalism was Marine Master Sergeant Don Saxon, who could field-strip and reassemble a machine gun in total darkness in a matter of seconds.

With the help of 122 gallons of tightly rationed gasoline from the embassy’s own allotment, Hemingway and his crew embarked on their quixotic search-and-destroy missions in June 1942. Code-named Friendless after Hemingway’s favorite whiskey-swilling cat, the operation sailed under the guise of a specimen-gathering voyage by the American Museum of Natural History.

Inspired by the World War I maritime exploits of German nobleman Count Felix von Luckner, who had bedeviled Allied supply convoys by disguising his own warship as a Norwegian fishing vessel, Hemingway formulated a plan of attack that made up in simplicity what it lacked in stealth. Once stopped by a U-boat, the crew of the Pilar would wait until a Nazi boarding party assembled on the deck of the sub, then open fire with their machine guns. After the deck had been swept clean, Hemingway’s professional jai-alai players would put their athletic skills to good use, lobbing hand grenades down the conning tower while their compatriots jammed a short-fuse bomb into the sub’s forward hatch.

Marine Colonel John W. Thomason, who recently had helped Hemingway edit an anthology of war stories, Men at War, before assuming his current post as head of naval intelligence in Central America, did not think much of the plan. “Suppose he stands off and blows you and Pilar out of the water?” Thomason wondered. “If he does that, then we’ve had it,” Hemingway admitted. “But there’s a good chance he won’t shoot. Why should a submarine risk attracting attention when the skipper can send sailors aboard and scuttle us by opening the seacocks? He’ll be curious about fishermen in wartime. He’ll want to know what kind of profiteers are trying to tag a marlin in the Gulf Stream with a war on.” In the not-unlikely event that he and the crew were taken captive, Hemingway had used his literary skills to throw together an official-looking letter of marque designating the Pilar and her crew as latter-day privateers. For his skepticism, the colonel earned the scoffing nickname, “Doubting Thomason.”

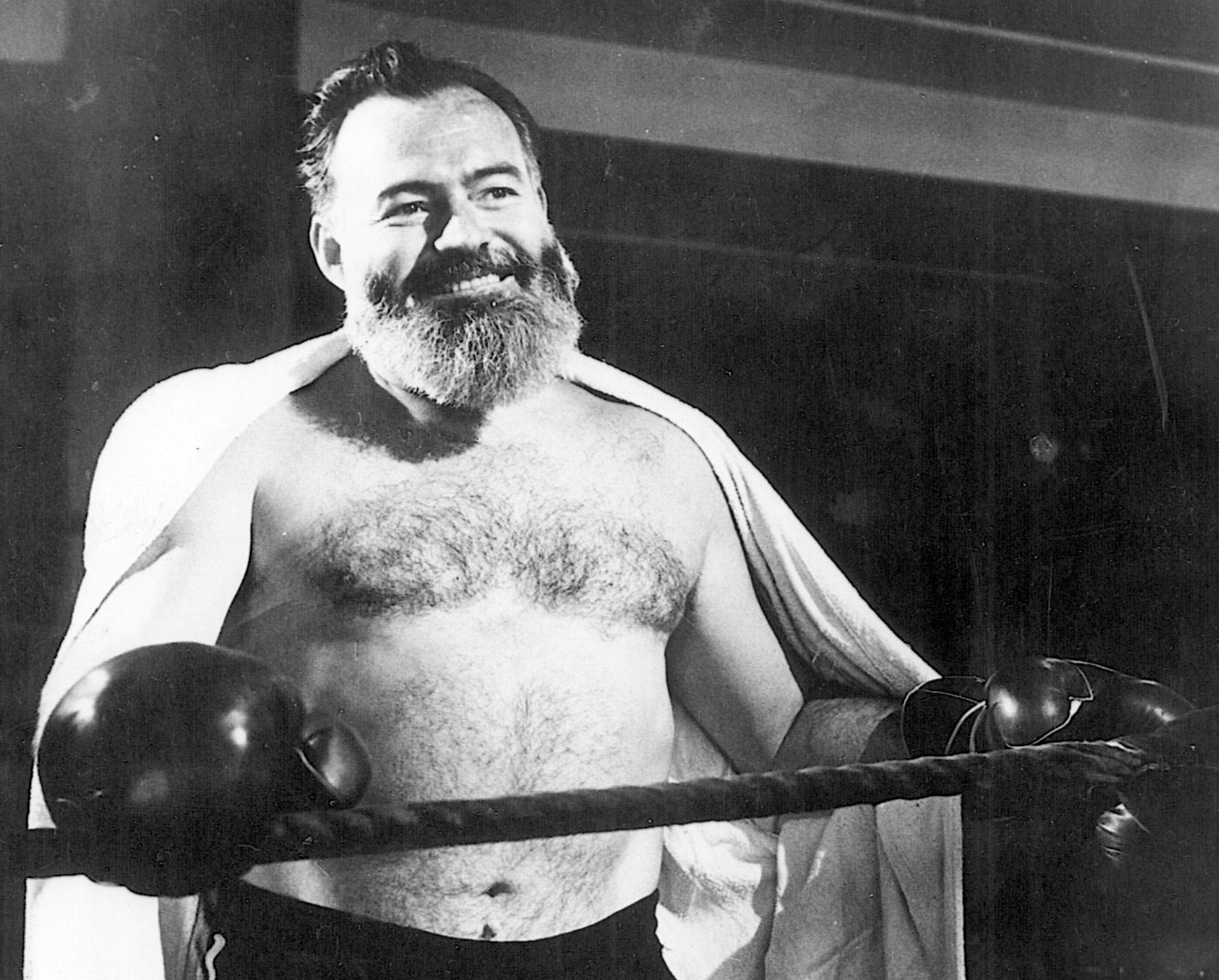

Actually, there was some reason to think the plan might work; Cuban fishermen regularly came into port with stories of being stopped by German submarines whose crews boarded their vessels and confiscated much-needed supplies of fresh water, fish, and vegetables. For days on end, Hemingway piloted the Pilar through the sun-dazzled Cuban waters, growing for the first time his famous beard to protect his fair skin from sunburn. The crew sighted several subs in the distance, but only came within striking distance once, when they observed a U-boat suddenly surface a few hundred yards away while the Pilar was anchored near an atoll at Megano de Casigua. Up close, the German sub seemed as large as an aircraft carrier, and Hemingway’s vessel immediately gave chase, but it was soon outdistanced by the submarine, which disappeared over the horizon in a puff of smoke.

Despite telling his friend A.E. Hotchner years later that “we were able to send in good information on U-boat locations and were credited by Naval Intelligence with locating several Nazi subs which were later bombed by Navy depth charges and presumed sunk,” Hemingway had little to show for his long hours at sea. Martha Gellhorn, who accompanied her husband on one fruitless voyage, considered the enterprise “rot and rubbish,” a transparent excuse for Hemingway and his buddies to co-opt scarce gasoline supplies to fuel their fishing and drinking excursions. On one such occasion, the writer revealed his penchant for drama—and also his courage—when he and his son Gregory were spearfishing near a reef on the edge of the Gulf Stream. Gregory, then 11, had tied a number of fish to his belt, where they attracted the attention of a trio of hammerhead sharks. The sharks began circling the boy, who screamed for help.

“Okay, pal,” Hemingway said calmly, “take it easy, throw something at them to get their attention, and swim toward me.” Hoisting his son onto his shoulders, Hemingway swam sidestroke to the boat while the sharks trailed ominously behind them. It was the closest they came to naval combat.

In the face of often-stated skepticism by FBI agents attached to the American Embassy in Havana, Hemingway disbanded the Crook Factory in April 1943. The author made no secret of his loathing for the well-pressed, buttoned-down agents, many of whom were Catholics, calling them “Franco’s Bastard Irishmen,” and on one occasion introducing an insulted G-man to the crowd at a jai-alai match as a member of the Gestapo. It was the start of a decades-long quarrel between Hemingway and the Bureau, which went out of its way to discredit the Crook Factory’s intelligence reports as totally worthless. Only Martha Gellhorn’s personal friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt prevented the FBI from forcibly closing down the operation months before its scheduled end.

The Pilar’s U-boat patrols also tailed off after the Allies finally managed to curtail much of the Nazis’ submarine success. It could not come soon enough for Martha, who had traveled to London as a war correspondent for Collier’s magazine and continually implored her husband to end his “shaming and silly life” as a submarine hunter and join her in England for the impending invasion of Festung Europa. Through her contacts at the White House, she managed to finagle Hemingway a flight to London aboard a Royal Air Force transport in May 1944, although it meant that she would have to take a perilous two-week cruise across the Atlantic aboard a cargo ship loaded with dynamite.

When the two Hemingways were safely in London, they immediately engaged in a screaming argument at the luxurious Dorchester Hotel. (The fact that Hemingway had usurped his wife as chief war correspondent for Collier’s, for which she had written since 1937, sharpened the fray.)

By then, the accident-prone author had managed to smash his head on a windshield during a drunken, late-night ride through blacked-out London, suffering a serious concussion and a scalp laceration that took 57 stitches to close. Martha, who had first heard of Hemingway’s accident when she debarked at Liverpool, was less than suitably sympathetic, at least in her husband’s eyes. When she saw him stretched out in bed at the hotel, swathed in an enormous bandage that looked like a turban and sporting a long beard that fell onto his chest, she burst out laughing. The reunion degenerated after that, and by the time Martha had left the room and slammed the door, Hemingway’s third marriage was as good as over.

Matrimonial problems aside, the author was more concerned just then with wangling a ringside seat to the D-day invasion. He had already alienated his British hosts through his ill-informed criticism of senior RAF pilots, whose temporary grounding (anyone with knowledge of the official invasion plans was prohibited from flying over enemy territory for fear of capture) he attributed ungraciously to cowardice. English poet John Pudney, his RAF liaison officer, was embarrassed for him. “To me,” said Pudney, “he was a fellow obsessed with playing the part of Ernest Hemingway and ‘hamming’ it to boot: a sentimental nineteenth century actor called upon to act the part of a twentieth-century tough guy. Set beside a crowd of young men who walked so modestly and stylishly with Death, he seemed a bizarre cardboard figure.”

Group Captain Peter Wykeham Barnes, a future British air marshal with five years’ experience fighting Germans in North Africa, the Middle East, and the skies over the English Channel, gracefully dismissed the author’s criticisms. “He impressed me,” said Barnes, “as the sort of man who spends his whole life proving that he is not scared.” By that time, RAF pilots had nothing left to prove.

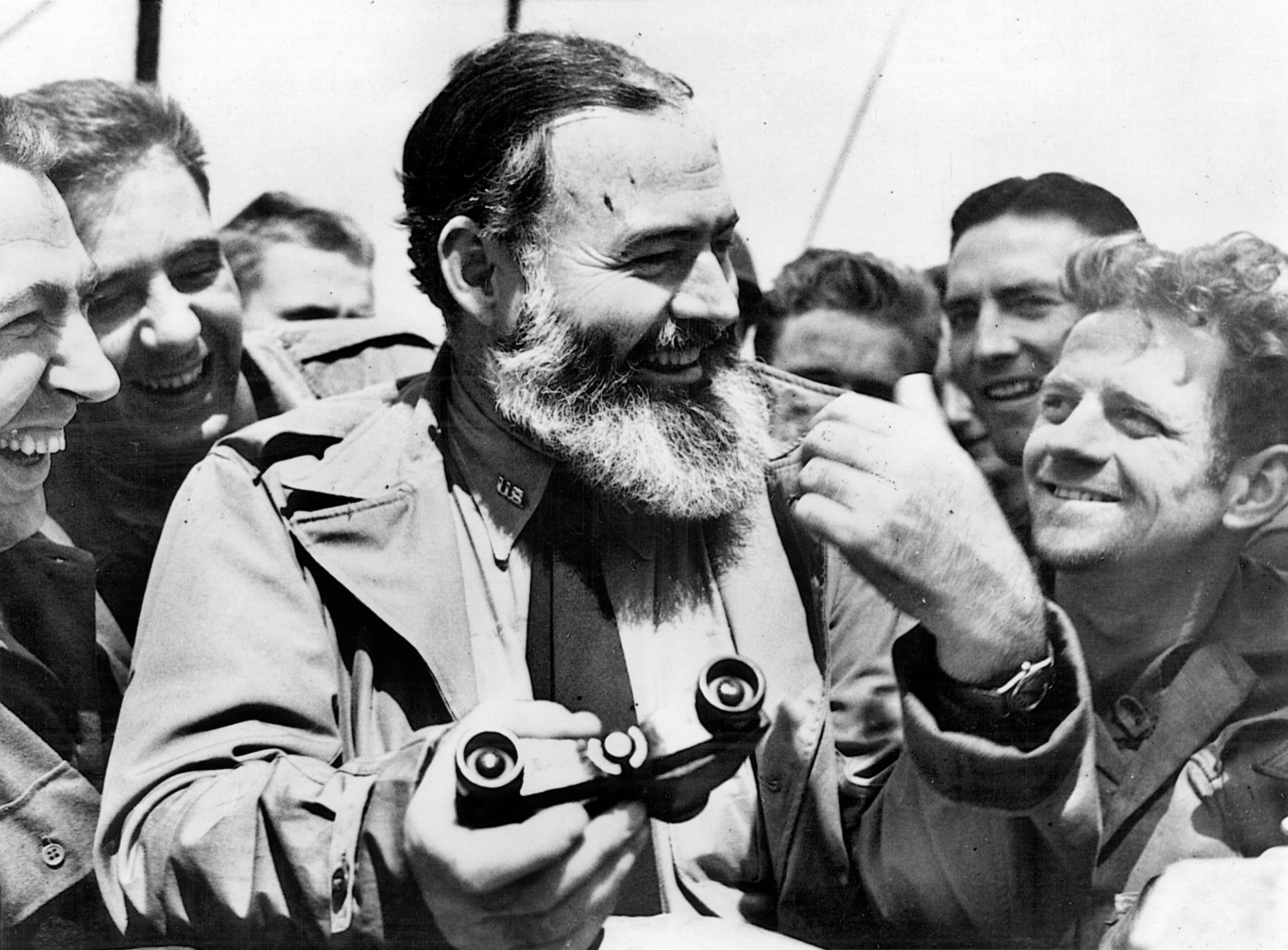

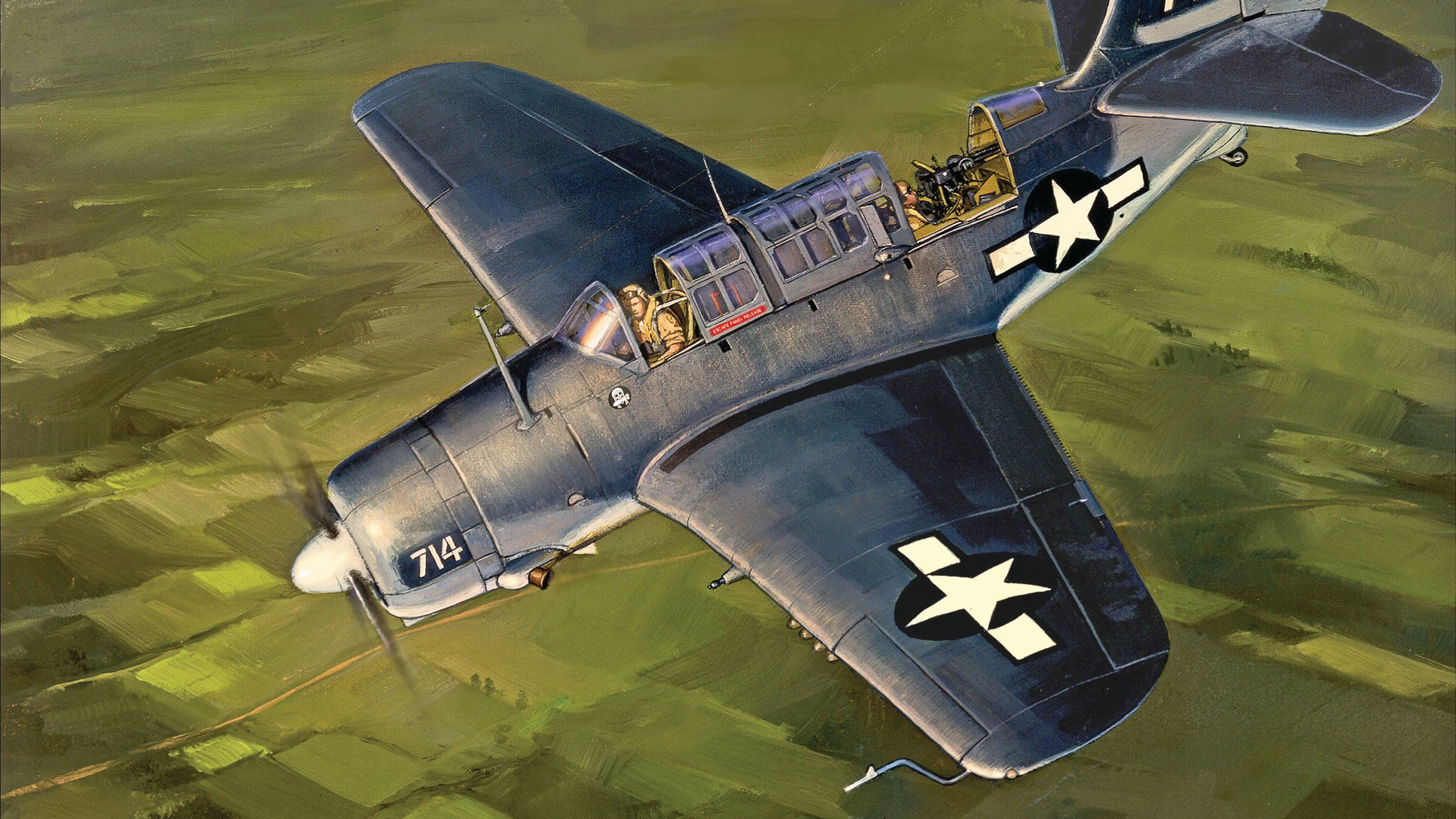

Despite his unmannerly criticism, Hemingway was taken aloft for a number of observation flights across the English Channel by Barnes and other RAF pilots. He was issued a standard blue uniform with shoulder patch marked “Correspondent,” along with a regulation escape kit consisting of a map of France drawn on a silk handkerchief, money, pills, and enough chocolate to last three days in the event he was shot down behind enemy lines. On June 2, he was briefed, along with hundreds of other war correspondents, on the upcoming assault, and then trucked to the southern coast, where three days later he boarded the attack transport Dorothea L. Dix in the predawn darkness to cross the Channel. At first light he transferred onto a landing craft to churn through the choppy waters toward the Fox Green sector of Omaha Beach.

Jammed into the LCVP with hundreds of helmeted soldiers packed shoulder to shoulder “like medieval pikemen,” Hemingway scanned the distant horizon with a pair of miniature Zeiss binoculars. He could make out the shadowy steeple of the ancient church at Colleville, along with the German machine-gun installations above the beach. Behind him the huge battleships Texas and Arkansas hurled 14-inch shells “like railway trains thrown skyward” at the grimly waiting enemy. On the beach itself, Hemingway wrote, “the first, second, third, fourth and fifth waves lay where they had fallen, looking like so many heavily laden bundles on the flat pebbly stretch between the sea and first cover.”

Allied destroyers running in “almost to the beach” blasted the Nazi pillboxes with 5-inch shells, and Hemingway saw with some satisfaction a three-foot piece of a German’s body, with the arm still attached, blown skyward by one such geysering shell.

After the LCVP, commanded by Lieutenant Robert Anderson of Roanoke, Va., dropped off its cargo of soldiers, bazookas, and TNT, it headed out to sea. Hemingway transferred back to the Dorothea L. Dix, where he began composing his highly colored account of the D-day landings, “Voyage to Victory,” which managed to give readers the wholly erroneous impression that the author had gone ashore personally at Omaha Beach. Many years later, True magazine printed an article by a former naval officer, William Van Dusen, that claimed that Hemingway had not only gone ashore on D-day, but had actually taken command of a combat rifle team that was pinned down on the beach by murderous German fire and led it to safety before crawling back across the beach to report his estimates of the battle to the beach commander. Van Dusen had gotten the ridiculous story directly from Hemingway.

The final straw to his marriage came when Hemingway learned that Martha Gellhorn had actually managed to go ashore, on D-day plus one, to help evacuate wounded soldiers to a Red Cross ship upon which she had stowed away by locking herself in the latrine. He never forgave her for it, nor for her tart observation that she, at least, “came to see the war, not live in the Dorchester.” By that time, her estranged husband had met the woman who would become his fourth wife, Mary Welsh, a staff writer for the London bureau of Time magazine, and he spent the next several weeks squiring the also-married Welsh around London, while the Allied forces began their painful and bloody breakout from Normandy into the hedgerow country of western France.

Still suffering from a concussion and a pair of banged-up knees, Hemingway did not make it to the mainland until mid-July, when he attached himself to Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton’s 4th Infantry Division, then preparing to spearhead the Allied breakout at St.-Lo. Through Barton, the writer met a cavalcade of high-ranking officers, in keeping with his own level of celebrity.

Unlike the war’s most famous correspondent, Ernie Pyle, Hemingway did not make it a point to socialize with lowly enlisted men, although he respected their professionalism and courage. As for Pyle, whom he never personally met, he nursed an undisguised loathing. “Ernie Hemorrhoid, the Poor Man’s Pyle,” he sometimes introduced himself to unsuspecting soldiers. Instead, he cultivated the company and friendship of regimental commanders, including Colonel Charles Trueman “Buck” Lanham, head of the 22nd Regiment, who became the writer’s closest wartime ally.

Armed with Grenades, Hemminway Followed

Lanham was an amateur poet himself, and he greatly admired the famous writer, whom he found “simple, direct, gentle and unaffected.” Hemingway accompanied the regiment as it drove south through La Denisiere, Villebaudon, Hambye, Villedieu-les-Poeles, and St.-Pois. He enjoyed what he called “a tough fine time with the infantry,” which engaged the enemy in a number of brief, deadly firefights in the hedgerows and wheat fields of the French countryside.

At Villebaudon, Hemingway acquired a captured German motorcycle and sidecar; General Barton obligingly assigned him a personal driver, Private Archie Pelkey of Potsdam, NY. Together, the two men sped down the dusty French roads toward the sound of machine pistols echoing in the distance “like a kitty-cat purring, but hard and metallic,” Hemingway told Mary Welsh.

On August 3, at Villedieu-les-Poeles, Hemingway, who was fluent in French from his years spent in Paris as a young man, learned from townspeople that a group of German SS men was hiding in the cellar of a nearby house. Hemingway armed himself with grenades and followed his guides to the house in question. Shouting down the stairs in French and German for the men to surrender, the author waited for a few seconds, then tossed three grenades into the darkness. “All right,” he said. “Divide these among yourselves.”

Hemingway did not go down to the basement to investigate, but he later boasted that he had killed “plenty” of Nazis—in direct violation of his status as a noncombatant journalist. The elated mayor of the village presented him with two magnums of champagne in recognition of his feat, and Hemingway gave one to Lanham when he roared through the town a few minutes later.

Two days later, Hemingway narrowly escaped death when he, Pelkey, and famed photographer Robert Capa (who had taken the haunting photograph of a Spanish partisan at the instant of his death in the Spanish Civil War) ran headlong into a German antitank gun on an S-curve outside St.-Pois. The three men scrambled into a ditch as the Germans opened up with machine-gun fire. Hemingway banged his head on a rock, suffering another concussion, and the men spent an uncomfortable two hours as enemy troops prowled through the surrounding hedgerows looking for signs of life.

Eventually, the Germans withdrew, and Hemingway, Pelkey, and Capa limped back to camp, dragging their badly shot-up motorcycle behind them. For the next several weeks Hemingway suffered from headaches, double vision, slurred speech, loss of verbal memory, and a ringing in the ears.

A few days later, Hemingway again escaped serious wounding or death, this time through a near-mystical experience. A German counteroffensive drove through the Mortain gap toward Avranches, heading straight for the 22nd Regiment’s command center at Chateau Lingeard, an old Norman castle. The chateau came under heavy shelling, and several regimental officers were killed or wounded, including Hemingway’s friend Colonel Lanham. Hemingway had been present at the chateau just prior to the attack but had unaccountably declined Lanham’s invitation to stay for dinner. Later, Lanham wanted to know why the author had been so eager to leave. “The place stank of death,” Hemingway said. His premonition had saved his life.

The American Army was now driving on Paris, and Hemingway detached himself from the 4th Infantry Division to join the more advanced 5th Infantry Division near Rambouillet. There he linked up with two truckoads of hardbitten French maquis, or partisans, who were scouting the roads leading into the capital city. American OSS Colonel David Bruce, in charge of intelligence operations in the area, eagerly recruited the French-speaking Hemingway, giving him a handwritten note that said the author was specially permitted to carry firearms and take part in military acitivities—a clear violation of the Geneva Conventions. At the same time, the author ripped the correspondent’s badge off his uniform, leaving only the four green ivy leaves of the 4th Infantry Division’s shoulder patch.

The Free French partisans, stripped to the waist and armed with Sten guns and captured German “potato-masher” grenades, took to the glamorous Hemingway immediately, addressing him as “Le Grande Capitaine” and following his directions without question. In his bedroom at the Hotel du Grand Veneur, Hemingway set up a command post for his “irregular cavalry.” (He later boasted that his scouting operations were “straight out of Mosby,” a reference to the redoubtable Confederate cavalry leader John Singleton Mosby.)

Despite his characteristic self-dramatization, Hemingway did render useful service as an interrogator of German prisoners and French civilians, although his pseudo-military bearing was too much for fellow journalist Bruce Grant of Chicago. When Grant complained loudly that “General” Hemingway and his maquis were hogging space in the hotel, Hemingway stalked over and punched Grant in the mouth.

Ammunition Popped Off Around Them Like Fireworks

The drive to Paris stalled for several days after the Allied High Command decided to give French General Jacques Leclerc, commanding the 2nd French Armored Division, the honor of liberating the city personally. Hemingway was furious at the politically inspired delay, and when Leclerc finally reached the front on August 22, he scornfully told Hemingway, David Bruce, and other intelligence officers to “buzz off” after they attempted to brief him on the situation. “In war, my experience has been that a rude general is a nervous general,” Hemingway advised Collier’s readers, and in private he took to calling the French commander “that jerk Leclerc.”

Hemingway joined the final rush into Paris on August 24, riding sidesaddle in his German motorcycle as his driver, Archie Pelkey, swerved around slower moving vehicles and dodged shellfire from both enemy and friendly artillery. The enemy had set fire to a block-long ammunition dump at Villacoublay, and the exploding ammunition whizzed in every direction. Pelkey, personally fearless and utterly devoted to Hemingway, thought the explosions were like the Fourth of July. “Sure is popping off, Papa,” he shouted happily.

Everywhere along the way the Americans were greeted by deliriously happy French citizens, who loaded down their vehicles with wine, fruit, flowers, whiskey, and pretty girls. Undaunted by an officious French lieutenant who told Hemingway and his “guerrilla rabble” to stay out of the way of General Leclerc’s troops, the writer “took evasive action” and sped down a side road until he caught up with the tanks at the front of Leclerc’s advance. “Paris was going to be taken,” Hemingway wrote in Collier’s. “I had a funny choke in my throat and I had to clean my glasses, because there now, below us, gray and always beautiful, was spread the city I love best in all the world.”

Dodging small-arms fire and answering French artillery, Hemingway, Bruce, and Pelkey drove headlong up the deserted Champs Elysees and pulled up to the door of the Travellers Club. The president of the club solemnly greeted the liberators with a champagne toast, which was quickly curtailed when a German sniper on the roof across the street began taking potshots at the participants. From there, the trio dashed through crowds of ecstatic Parisians to the Café de la Paix, then on to the Ritz Hotel, where they secured lodging for the night and immediately ordered 50 martinis.

After the liberation of Paris, about which Hemingway typically exaggerated his own minor role, the author rejoined Colonel Lanham and the 4th Infantry Division at Pommereuil on September 3. The regiment had played a large role in driving the Germans through France and into Belgium, taking over 2,000 prisoners along the way.

Lanham, hearing that Hemingway was living the high life at the Ritz, sent him a mocking note, not expecting the author to attempt to reach the front lines. But Hemingway, taking the note as a challenge to his masculinity, started immediately for the front. En route, he and his driver, a Free French partisan named Jean Decan, had to dodge pockets of German infantry fighting desperately to get back to the Siegfried Line. One night, camped in a wheat field, Hemingway and Decan witnessed five V-2 rockets arcing across the sky toward London.

Hemingway accompanied the 4th Division as it drove through Belgium and crossed into Germany on September 12, at the town of Hemmeres. At an officers’ mess in a farmhouse at Buchet, Hemingway again displayed his larger-than-life bravado when an enemy 88mm shell came screaming toward them and exploded in the barnyard outside. Everyone but Hemingway hit the floor; he continued eating as though nothing had happened. When Lanham ordered him to take cover, Hemingway refused, saying that “you were as safe in one place as another under artillery fire unless you were being shot at personally.” Besides, he reasoned, if you could hear a shell coming ahead of time, it could not hit you. Hemingway’s behavior, said sketch artist John Groth, who was present at the scene, was both “impressive and insane.”

On October 4, Hemingway received orders to report to Third Army headquarters at Nancy to answer charges that he had violated the rules of war by taking part in the military actions around Rambouillet. The charges, inspired by complaints from disgruntled colleagues such as Bruce Grant, were true. If proved, they would result in Hemingway’s being expelled from France. Attributing the charges to a bunch of “ballroom bananas,” the author denied under oath that he had ever commanded troops or handled weapons during the weeks preceding the liberation of Paris. To buttress his claim, he produced signed testimonials from Colonel David Bruce and Major James Thornton, the ranking American officers at Rambouillet, who praised Hemingway for his “welcome assistance” and denied the accusations that he had violated the Geneva Conventions. The charges were dropped, and Hemingway, after a few weeks in Paris with his new love, Mary Welsh, went back to the front in time for the disastrous American offensive in the Hürtgen Forest.

Fighting Off Attackers with a Thompson

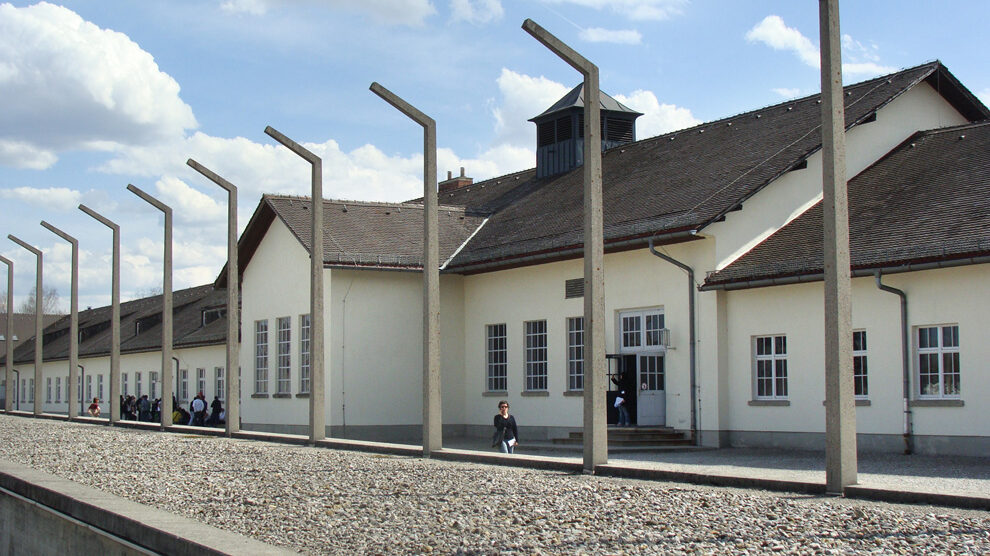

For two and a half weeks, between November 15 and December 4, Hemingway witnessed some of the war’s most ferocious fighting. Commanding General Dwight D. Eisenhower sent American forces plowing eastward in an ill-conceived attempt to drive the German forces back across the Rhine and into their homeland before the end of the year. The 4th Infantry Division was given the task of clearing a path through 50 miles of densely wooded hills west of Düren. It was a haunted landscape, filled with icy streams, rocky ravines, and gloomy forests, and lashed by bitter winds, sleet, and driving rain. The Germans were well dug in, with buried pillboxes, presighted artillery, and deadly minefields.

Colonel Lanham’s regiment was virtually decimated in the close combat, suffering 2,678 casualties in 18 days of fighting. Lanham himself narrowly escaped death, thanks in part to Hemingway. When a German platoon assaulted Lanham’s command post on November 22, Hemingway helped fight off the attackers with a Thompson submachine gun.

The Hürtgen Forest campaign was a dismal failure, and Hemingway returned to Paris in early December, suffering from a severe case of pneumonia. He insisted on rejoining the regiment after the German counteroffensive known as the Battle of the Bulge, but was so ill that Lanham immediately handed him over to the regimental physician, who put his famous patient to bed with a massive dose of sulfa drugs.

On December 22, Hemingway watched a regiment of the 5th Infantry Division, clad in camouflage uniforms made from sheets, attack across a three-mile front. It was the last hostile action he witnessed during the war. After a holiday dinner at General Barton’s headquarters in Luxembourg, Hemingway returned to Paris for the winter, then hitched a ride back to the States aboard an Army Air Force transport in early March 1945.

Hemmingway’s Private War

Unlike his experiences in World War I and the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway’s World War II adventures did not provide him with the makings of a great novel. He never finished a planned, three-part book covering the war at sea (his U-boat hunting along the Cuban coast), in the air (his observation flights with the RAF), and on the ground (the infantry campaign in France and Germany). Instead, in 1950 he published the badly received novel Across the River and into the Trees, which followed the romantic misadventurers of a dying Army colonel in postwar Venice. Many of the colonel’s wartime memories were direct transcriptions of Hemingway’s own experiences with the 22nd Infantry Regiment, clumsily transmogrified into an aging roué’s laments for his youth.

The book received the worst reviews of Hemingway’s career, bringing to a close what had been perhaps the least creditable period of the author’s life. While much of the world had been struggling to survive the deadly ravages of fascism and totalitarianism, Ernest Hemingway had been fighting a battle with his own worst impulses—alcoholism, egotism, and a tendency to see everything, even the greatest war in human history, through the narrow prism of his own self-interest.

The Allies won their war, but in many ways Hemingway lost his own, beginning a downward spiral of drinking, drugs, and depression that would end with his suicide 16 years later. The man who had witnessed firsthand so much of the 20th century’s worst fighting, from the trenches of World War I to the savage guerrilla fighting in the Spanish Civil War to the grinding overland drive to Berlin in World War II, put a shotgun to his forehead in the hallway of his Ketchum, Idaho, hunting lodge on July 2, 1961. The last death he witnessed was his own.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments