By Michael Haskew

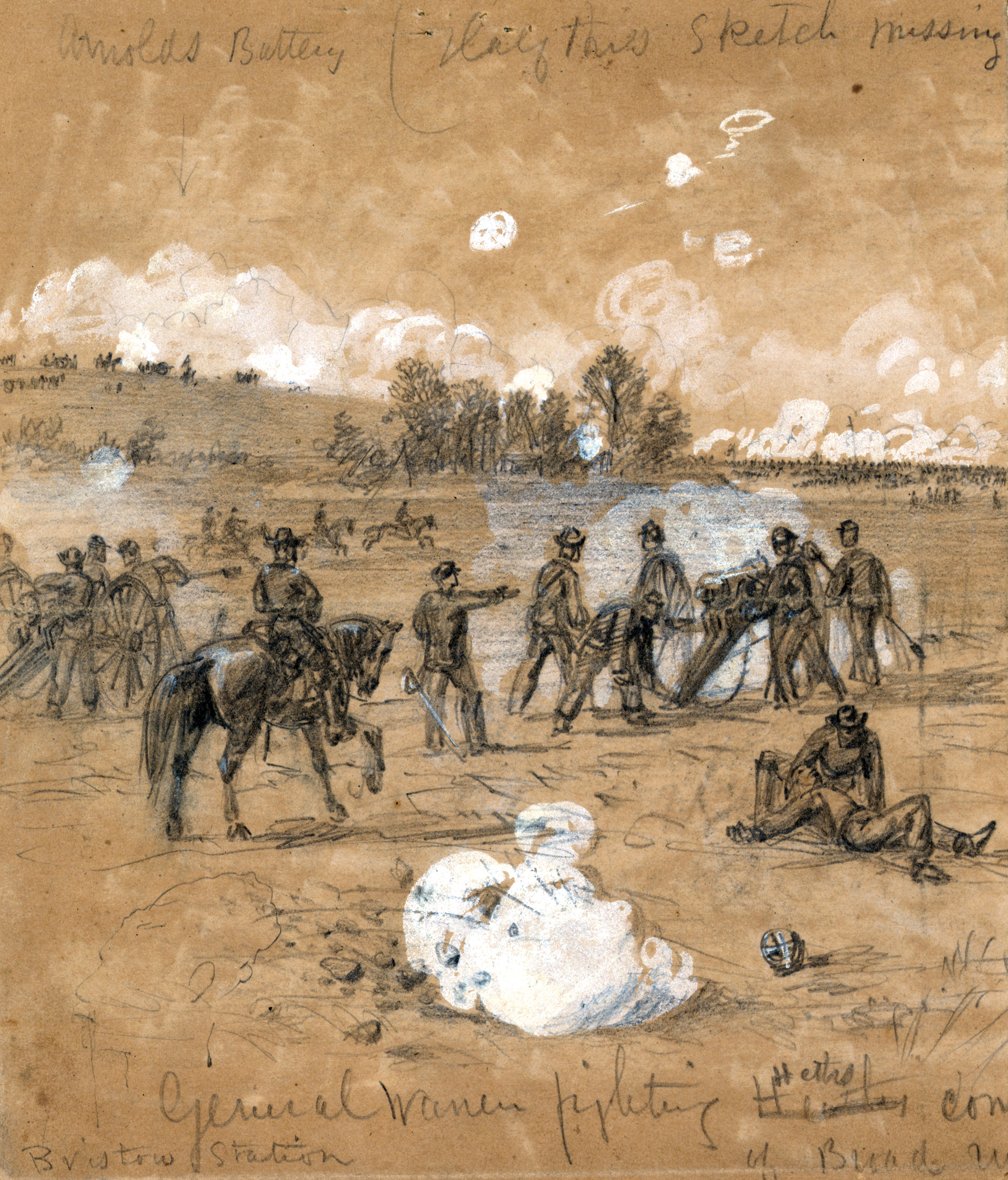

An artillery officer early in his military career, Napoleon Bonaparte understood the potential for big guns to influence the outcome of a major battle. He deployed his 84-gun Grand Battery at the Battle of Waterloo, and just after 1 PM on June 18, 1815, gave the order to bombard the center of the Duke of Wellington’s line on the ridge of Mont-Sainte-Jean.

Wellington had deployed the bulk of his army on the reverse slope of the ridge, and rainy weather had left the ground soggy. These factors combined to minimize the effectiveness of the thunderous French barrage. Therefore, the advance of the French I Corps, under the command of Marshal Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Comte d’Erlon, would encounter stiff resistance as it ascended the slope of the Allied-held ridge. Most of the Allied troops d’Erlon faced were veterans of the earlier Peninsula War under the command of Lt. Gen. Sir Thomas Picton. These disciplined troops offered stiff resistance. Meanwhile, the farmstead of La Haye Sainte anchored Wellington’s center, and its British and German garrison poured effective fire into the advancing French infantry as artillery shells tore great gaps in their ranks.

Undaunted, the French pressed forward and reached the crest of Mont-Sainte-Jean. For a brief time it appeared that they were on the brink of victory. Swift reorganization and a rapid advance might actually rupture the Allied center. However, at the critical moment Picton ordered his available soldiers, including a brigade of Scottish Highlanders, to rise from the cover of the reverse slope and loose a deadly volley. The French were staggered, but still they came on with cuirassiers, cavalrymen wearing breastplates of armor, charging into the fray. Picton was shot dead with a bullet in his temple.

At the critical moment, Wellington countered. While the relative handful of British soldiers and men from the King’s German Legion stood firm at La Haye Sainte, the Iron Duke ordered the Household Brigade and the Union Brigade, fresh heavy cavalry units, to charge the exposed French flanks. The British horsemen, including the now famous Life Guards, Royal Regiment of Horse Guards, King’s Dragoon Guards, 1st Royal Dragoons, 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, and the Scots Greys, thundered forward in an avalanche of man and beast. The charge broke the back of the French assault, and three of the four divisions under d’Erlon’s command fell back in disarray. About 3,000 French prisoners were taken. Still, for the gallant British horsemen there was a price to be paid.

Once their blood was up, the British cavalry swept on toward French artillery emplacements, slashing at the gunners. However, the furious charge had spent the energy of the their horses. In their haste they had overextended their advance. The French regrouped and began to close in on the exposed cavalry brigades from all sides. During their fighting retreat, the British horsemen were ravaged by rifle fire and a coordinated countercharge by French lancers. Roughly half their number were killed or wounded. Wellington had spent his cavalry reserve, but despite the heavy losses the gallant charge had temporarily stabilized the situation in his center. The action also bought more precious time for the Prussian Army to reach the field at Waterloo.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments