By John W. Osborn, Jr.

Compared to its sprawling British counterpart, the French colonial empire produced few notable heroes. One of these was Henri Laperrine, a talented but troubled officer who would help tame his part of the wilderness but, ultimately, would be destroyed by it. Laperrine, born in 1860, was burdened by a wastrel officer-father who bankrupted the family and became notorious throughout the army for his incompetence and dissoluteness. A marshal of France, inspecting Laperrine and other cadets at the St. Cyr military academy, asked him pointedly: “Didn’t I know your father? Well, tell him I’ve never forgiven him.”

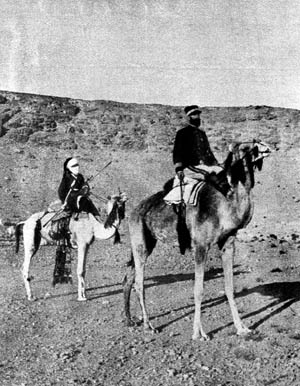

After graduating from St. Cyr, Laperrine was initially posted to France’s North African colonies of Algeria and Tunisia. Bored with garrison life and inherently unsociable (he would never marry or show any interest in women, unlike his friend and fellow St. Cyr cadet Charles de Foucauld), Laperrine volunteered in March 1889 for service considered so dismal that even the Foreign Legion avoided it. He moved south into the sprawling Sahara with Senegalese spahis.

The Scorpion and the Tuareg

France had laid claim to territory comprising modern-day Chad, Mali, and Mauritania, with visions (which would prove to be nothing more than sun-baked mirages) of vast mineral wealth and a modern railroad to carry that newfound wealth across the blazing sands. Blocking the way were the various indigenous tribes of the region, none of whom was exactly welcoming to foreigners. Most dangerous of all were the fierce Berbers of the Ahaggar and Tassili-n-Ajjer Mountains, who effectively controlled the oases and caravan routes. They called themselves the People of the Veil, but they were better known by the name their Arab enemies gave them, the Tuareg—or “abandoned by God.” As an old Arab saying had it, “The scorpion and the Tuareg are the only enemies you meet in the desert.”

The French would find that out the hard way, after several exploring and military expeditions had been wiped out by the Tuaregs. Laperrine and the future victor of the Marne and marshal of France, Joseph Joffre, came upon one such annihilated group in early 1894. “In a clearing, at the foot of a thick bush, was a mass of corpses, probably those of the tirailleurs, while in the middle and south, other bodies lay in various postures,” Joffre wrote years later. “We left the place with a sense of quiet and powerless rage which is extremely trying.”

Laperrine took out his anger by leading counter-raids with his spahis. In one punitive raid that attracted much attention back in France, he tirelessly tracked a Taureg raiding party and led a nighttime assault against their encampment on horseback, jumping the barricade, emptying his pistol, and thrusting his sword into a mass of scrambling tribesmen. Frenchmen safely at home in their comfortable bourgeois beds were enraptured by the romance of Laperrine’s strike: the brave French captain riding through the cold desert night at the head of his tiny force, the brilliant African stars overhead, the measured, spongy thud of the camels’ hooves contrasting with the rhythm of the spahis’ horses as they raced forward on a mission of fire and retribution.

Pacifying the Sahara

After two years in the desert, Laperrine was posted back to France by the Army. He returned to Africa in June 1901 as a major and first commander of the oases, whose mission it was to organize a new force to pacify the Sahara once and for all. Previous efforts had cost the nation more than 50 million francs.

The idea of recruiting the Tuaregs’ traditional desert enemies—the Chaamba, Tuat, Tidilkeit, and Gourara tribes—did not originate with Laperrine, but he was undoubtedly the officer best suited to carry it out. It took a special kind of officer to command a mixed-native unit. Mastering the various languages and the art of camel riding were the easiest requirements. The men themselves had to be treated with as much tact as the truculent animals they rode. One had to be sensitive to the subtle tribal and racial hierarchies, which determined social relationships in the desert. Arabs would not serve with Tuaregs, and no one would serve with blacks or slaves. One also had to be prepared to put up with a certain amount of insolence and lack of respect—every man who carried a rifle considered himself a lord. There were no salutes, parades, or military discipline. If a trooper was unhappy, he simply took his camels and departed. It was a system adapted to the special needs of the desert, and as Laperrine instinctively recognized, it was the only one that worked.

Laperrine drew recruits mainly from the Chaamba, organizing and supplying them into three 300-man camel companies led by French officers. He typically sent them out on long-range patrols of 20 men each. “Unless one has led one of these trips, or taken part in a similar policing operation, one cannot imagine the excellent character of our Saharians,” wrote Laperrine. “Their resilience in the face of fatigue, hunger and thirst is a matter of amour-propre. There is never a complaint, even when circumstances are such as the chief is obliged to repeat the miracle of the loaves and fishes. When reading them their evening orders I have often had to include instructions of the following kind: for such-and-such reason we cannot get fresh supplies until this time instead of that time; I’ve given you provisions to last from April 15 to 30; you’ll have to make them last to May 8. I’ve given you three days’ water; but from the latest information, it seems that we will not reach another well until noon on the fifth day; you will have to be sparing with your water. I wonder how these orders would be received by any other company in the Sahara?”

Though he looked more like a mild-mannered postal clerk than a hard-riding cavalryman or a skilled diplomat, Laperrine quickly showed that he could match his desert recruits in endurance, spending 10 hours a day on camelback in 120-degree heat and letting scorpions crawl all over him at night in the dark. His strenuous training efforts were to bear fruit on May 7, 1903, in the decisive action in the French pacification of the Sahara, the battle at Tit oasis.

Battle at Tit Oasis

Lieutenant Gaston Cottenest had camped southwest of the Ahaggar Mountains with 100 men and sent another 30 out scouting the countryside. At 4 pm he suddenly came under attack by at least 300 Tuaregs. The Tuaregs charged on camelback, threw their lances, then dropped off their camels, sword in one hand, rifle in the other, to rush hacking into the Saharians. “Before this human wave which continued to advance without stopping and without firing, we withdrew little by little behind our convoy,” Cottenest recalled. “We were outflanked and they were going to surround us completely, when I ordered my men to rally at the top of a small hill of boulders and sand.”

Cottenest held the summit while the Tuaregs crawled around the boulders, some to within 25 yards of the Saharians, keeping up a steady fire. “We would see behind the rocks which protected them a head, a puff of smoke and then everything disappeared,” wrote Cottenest. After an hour of fighting, Cottenest was running low on ammunition when some of the Tuaregs abruptly decided to abandon the fight to loot the Saharians’ camels. At the same time, the patrols Cottenest had sent out earlier suddenly returned. Seeing the surprise they caused on the enemy, the Saharians suddenly charged down the hill into the Tuaregs. What followed was described by Cottenest as a “violent hand-to-hand fight, the butts of rifles broke over skulls.” The Tuaregs fled in disorder.

Cottenest brought back from Tit three dead and 10 wounded, but he left behind some 94 enemy dead. Another French officer visited the scene months later and described the battle site as “a real charnel house. The ground is littered with the bodies of camels and horses, above all in the depression where the convoy was located. The Tuaregs have not buried their dead: they have left them where they fell, almost all on the rock itself, and have raised only small pyramids of stones. Through the chinks of these primitive tombs, one can clearly distinguish the Tuaregs stretched out fully clothed, just as they were on the day of the combat. Decomposition has done its work, and the corpses are literally spread out on the ground. It has been six months since the battle, but this cemetery still reeks of an insupportable stench.”

“Initiative Does Not Mean Indiscipline”

The Battle of Tit effectively broke the back of tribal resistance to the French in the Sahara. After the battle, Laperrine’s patrols seldom had to fire a shot; one patrol crossed the desert four times during the hottest period of the year without losing a man or a camel. Formerly shunned, Sahara service under Laperrine suddenly became one of the most sought-after postings for colonial officers. “I am free to follow my ambitions in a country where healthy adventure is still possible,” wrote one officer. “I command and I organize. I do not have to make any reports until the end of the expedition. Post is rare—thank God! I don’t want to hear anything about Europe, where I would be a tiny stick in the current. Here I am one of the first in an epoch where everyone is starting off under a new administration.”

One by one, the desert tribes came in to make their formal submission to Laperrine. On August 25, 1905, the conquest of the Sahara was completed when Laperrine ceremonially draped the leader of the Ahaggar Tuaregs with a red burnoose to symbolize the honorary position given to him by France. Some Tuaregs even joined Laperrine’s camel corps.

But Laperrine himself would soon have to submit to French authority. He had once written, “Initiative does not mean indiscipline.” Paris did not see it that way when he sent patrols probing into Turkish-held Libya, provoking a diplomatic contretemps. One step ahead of being relieved, he requested a transfer back to France on November 8, 1909. The next five years passed quietly for the old desert warrior. Then came World War I.

Avenging Foucauld: 103 Names

Reentering active service, Laperrine was serving as a colonel on the Western Front when the Turks encouraged unrest among the Tuaregs. The situation became a crisis in December 1916, when a Tuareg raiding party murdered Laperrine’s old St. Cyr classmate and friend, Charles de Foucauld. The irrepressible Foucauld had given up his playboy-officer’s lifestyle to become a monk, living an ascetic existence among the Tuaregs. To his admirers, Foucauld was a modern-day St. Francis of Assisi. To skeptics—and there were many—he was an impractical, if well-meaning, fanatic. Apparently, some of the Tuaregs inclined to the latter opinion.

Laperrine returned to the Sahara to reassert French control and seek revenge, carrying with him a notebook containing 103 names of the raiding party that had attacked his friend, vowing to hunt them down and cross off the names as he did. He found his once-proud camel corps had become a shambles, its officers demoralized. He whipped the corps back into shape, got them back out on patrol, and by January 1918, he had the situation in the Sahara once more under control.

He largely failed in his other mission, however. Laperrine managed to locate and kill seven raiders in a surprise attack on their camp; some of Foucauld’s few meager possessions were found with them. But it was not until 1922 that the Tuareg who had actually fired the fatal shot into Foucauld was hunted down and executed.

Lost to the Desert

By then, the Sahara, twice conquered by Laperrine, had its final victory over him. In February 1920, recently promoted to brigadier general, Laperrine boarded a flight to pioneer an air route from Algiers to Dakar. The aircraft became lost, ran out of fuel, and crashed. A search party of Laperrine’s camel corps found two survivors 21 days later.

Laperrine was not one of them. Badly injured in the crash, he had suffered terribly for two weeks in the more than 100-degree heat. Five days before the rescue party arrived, he had tried to crawl away to die—it was the desert tradition.

Brought back to camp by his companions, Laperrine’s last words before sinking into a final coma were: “People think they know the desert. People think I know it. Nobody really knows it. I have crossed the Sahara ten times and this time I will stay here. I am sorry. I have failed you.” He made his last journey on camelback, wrapped in airplane cloth, to the hermitage of Tamanrasset, where he was buried next to his old friend Charles de Foucauld. The two had come a long way from St. Cyr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments