By David H. Lippman

The director flicked his finger, and General Charles de Gaulle began reading his address into the British Broadcasting Corporation’s microphone, speaking from London to his defeated countrymen across the English Channel, calling upon them to continue resistance in the face of overwhelming German supremacy.

The date was June 18, 1940, and Charles de Gaulle, tall, confident to the point of arrogance, one of the few French generals who saw the value of armor and mobility, was defying his head of state, Marshal of France Henri Philippe Pétain, challenging Pétain’s announcement the day before that France would seek armistice with Germany and accept crushing defeat.

“Nothing is lost,” De Gaulle told his listeners, “because this war is a world war. In the free world, immense forces have not been brought into play. Some day these forces will defeat our enemies. On that day, France must be present at the victory. She will then regain her liberty and greatness. That is my goal, my only goal! This is why I ask all Frenchmen, wherever they may be, to unite with me in action, in sacrifice, and in hope. Our country is in danger of death. Let us fight to save it.”

Charles d Gaulle: “Une Peste”

Few Frenchmen heard de Gaulle’s speech. Most were not listening to BBC radio in the third week of June 1940. Hitler’s panzers had crushed the mighty French Army, first by exploding through the Ardennes, destroying three armored divisions, and forcing the British to evacuate from Dunkirk. Shorn of much of their industrial region and armor, the French had mounted a determined but doomed defense of their heartland, which ended days after the Nazis strutted into an intact Paris. Defeatist and pro-Fascist French leaders like the shifty Pierre Laval, the aged and senile Pétain, and Premier Paul Reynaud’s scheming mistress, Helene des Portes, forced Reynaud out, pushed Pétain in, and he immediately called for an armistice.

The victorious Germans were happy to grant it—handing over harsh but honorable terms to the French delegation on June 22, 1940, in the same railway car that Marshal Ferdinand Foch had used back in 1918 to extract the armistice from Germany that had ended World War I, on the same site at Compiegne.

At the ceremony, Adolf Hitler sat quietly while his top military manager, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, read out Germany’s grievances against France and the armistice terms. France would keep a version of its independence in a new state, based out of the southern spa town of Vichy. The Third Republic and its values of “liberty, equality, fraternity,” would be replaced by the “French state,” under Marshal Pétain, and its core (stamped on thin aluminum coins) of “work, family, fatherland.” Northern France would be occupied. Most of the French military would be disarmed, the troops held as prisoners of war, and France’s economic assets yielded up to the invader.

Yet there was still some honor. The new Vichy government would enjoy a measure of independence and neutrality in the continuing world war. It would control the formidable French Navy and the large French empire, which included such proud holdings as Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Indochina, and Senegal, down to small territories like Martinique, St. Pierre and Miquelon, and Reunion.

But these seemingly honorable armistice terms meant little to Charles de Gaulle, who had just been fired from his position as undersecretary of state for defense. De Gaulle, unlike his aged and perfidious colleagues, proposed to continue fighting the “Boche” from the empire. The colleagues regarded de Gaulle as “une peste,” a jumped-up colonel holding a wartime brigadier general’s rank, whose ideas of continued fighting would only mean a final and dishonorable defeat.

With 100,000 francs and a promise of British support, de Gaulle fled Bordeaux for England on June 17 and made his broadcast from London the following day.

Condemned to Death For “an Excess of Patriotism”

There was no reaction at first. So de Gaulle went back in the BBC studio the following day and tried again. This time, there was an answer—from the Vichy government, which ordered de Gaulle back to France and warned that his statements were not those of the government and should be ignored. De Gaulle ignored his nominal Vichy bosses. The Vichy government promptly put de Gaulle on trial in absentia, charging him with high treason, and on August 2 condemned him to death.

The court-martial was pointless, though. Pétain himself wrote in the margin of the paperwork, “The sentence in absence can only be academic. It never entered my mind to put it into effect.” Laval added, “You can’t condemn someone to death for an excess of patriotism.”

But by now the battle lines between de Gaulle and Vichy were drawn. More importantly, Vichy had served de Gaulle by publicizing his call to arms, and it was now filtering through France and its empire. Four Vichy newspapers reprinted it, French proconsuls across the empire read it, and de Gaulle himself tramped across England, speaking to interned French troops and warship crews, seeking recruits. He got some: most of the 13th Demi-Brigade of Foreign Legionnaires; some French Marines in Cyprus and Egypt; airmen and sailors who had fled France at Dunkirk; some 133 fishermen from the island of Sein who sailed across the Channel rather than submit to Hitler; Lt. Cmdr. Thierry d’Argenlieu, a monk-turned-sailor, who headed the French Navy in its Pacific holdings; Admiral Emile Muselier, who had been sacked by Admiral Francois Darlan at the war’s outbreak. By August, de Gaulle had about 7,000 men in his embryonic army, split between England and Egypt.

By August, however, relations between the average Frenchman and Briton had broken down because of an astonishing act by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Royal Navy, which led to British ships firing on and sinking Vichy warships.

Sinking the French Fleet

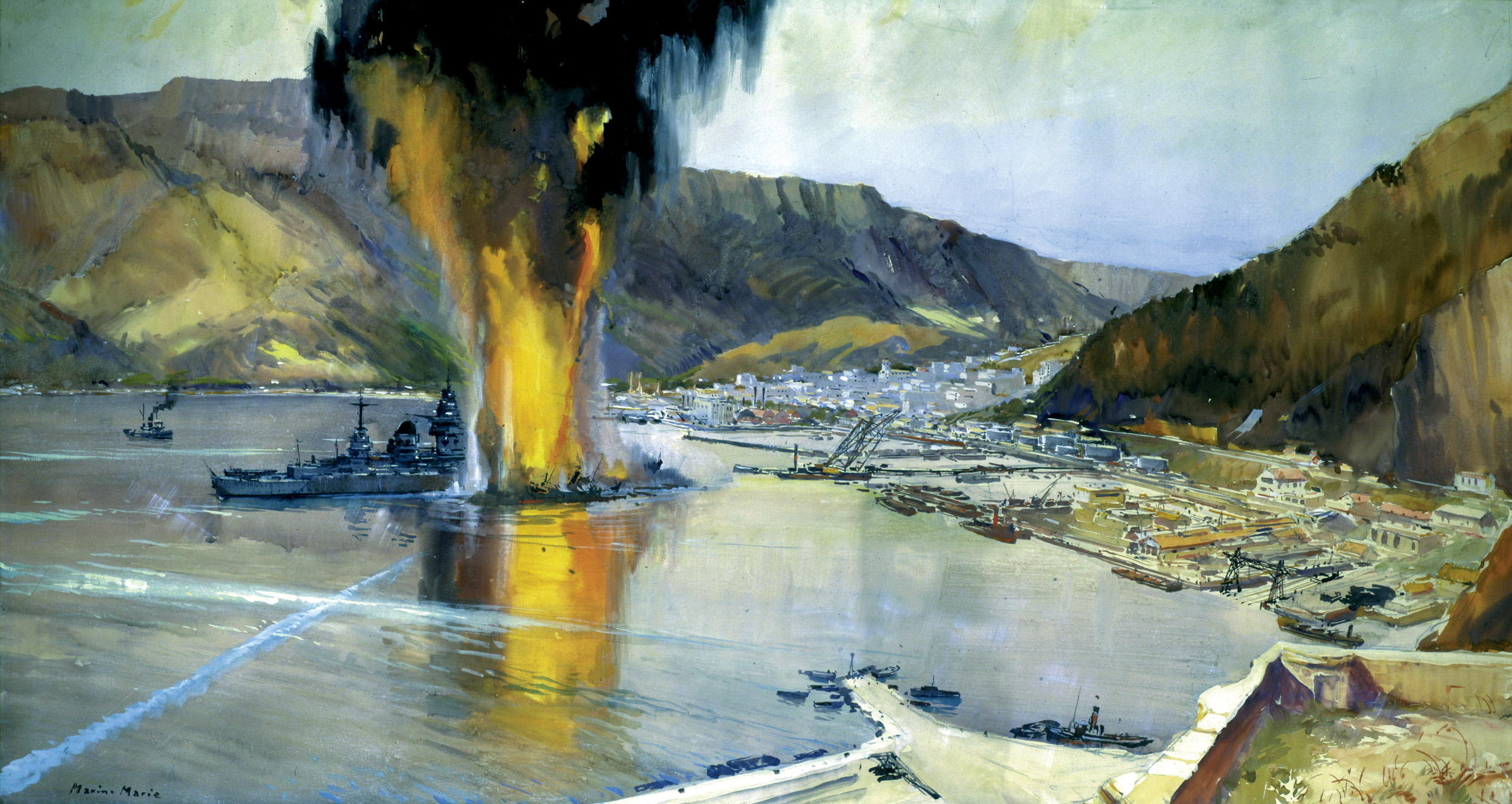

Hanging in the balance of the German-French armistice was the modern and powerful French Navy, which included two battle cruisers, seven battleships, and a large number of cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and support ships. In German hands, they could tip the scale of naval power in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. The British had to prevent the Germans from taking over these fast warships. Two battleships, Lorraine and Courbet, were in British ports and were at least out of the game. But the new battle cruisers Dunkerque and Strasbourg and the older battleships Provence and Bretagne were at Mers-el-Kebir, near Oran in Algeria, and the even newer battleship Richelieu, packing eight 15-inch guns, was at Dakar on the Senegal coast. The British could not let Germany seize them.

On July 3, 1940, the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean squadron appeared off Oran and issued an ultimatum to the French fleet, giving three choices: disarm on site, join up with Britain, or face destruction at the hands of British guns. Admiral Gensoul, commanding the French ships, refused the options, so the British opened fire. Dunkerque and Strasbourg were seriously damaged, Provence beached, and Bretagne sunk.

The Vichy French were furious and fumed bitterly over the insulting and apparently treacherous behavior of their former ally, but British morale and American politicians were impressed—if nothing else, the British would fight on for survival.

Four days later, the British struck again at the Vichy fleet, this time at Dakar, where the brand new battleship Richelieu was at anchor to avoid seizure by either side. Richelieu was a formidable ship. Displacing 38,500 tons, she could cut the waves at more than 30 knots and packed eight 15-inch guns and nine 6-inchers. A match for anything afloat, she could provide either Hitler with a shortcut to sea power or de Gaulle’s Free French with a prodigious amount of gunnery.

The British, with sang-froid, hit Richelieu first, sending in a motor boat by night that dropped depth charges under the battleship’s stern. The depth was too shallow for them to get off. At dawn, the British sent in six antique Fairey Swordfish biplanes from the old carrier HMS Hermes, and despite the seeming mismatch of biplanes and battleship guns the old aircraft did their job, punching a hole in the battleship’s stem. Dakar’s limited dockyard facilities could not repair Richelieu, so she was immobilized but still able to fire her main battery.

The French broke off diplomatic relations with Britain on July 5 to retaliate for the attacks—they could do little more—and Britain’s diplomats in Dakar reported to London on their return that the French colonists and military there were ripe to split from Vichy. The information was inaccurate—the French troops in Dakar were actually merely angry over German demobilization orders, which cut their numbers and paychecks—but the reports fueled ideas in Britain’s War Office and, more importantly, with de Gaulle.

The Strategic Port of Dakar

The French general, having assembled an embryonic army, now sought a physical base. So far, France’s proconsuls were sticking with Vichy. But if he could establish himself on French colonial soil, he might set off a string of colonial dominoes and gain the support of France’s far-flung holdings and their manpower and resources. Dakar, sitting at the center of French West Africa, a major seaport standing astride the Atlantic sea-lanes, hosting a prestigious if immobile battleship, could be that place.

Another factor in favor of Dakar: the French, Belgians, and Poles had shifted their gold reserves there before conquest, and the stacks of bullion would be critical Allied economic assets.

At the same time, de Gaulle finally got some real backing. Felix Eboué, the black governor of Chad, overthrew the Vichy military, put Colonel Philippe Hautecloque (known to history as Jacques LeClerc) in command, and rallied to de Gaulle. Eboué’s gutsy move set off a chain reaction in French Equatorial Africa, and Gabon, the Cameroons, and the French Pacific territories joined up with Free France. De Gaulle now had a base of support. But Dakar stood between him and Brazzaville, the capital of the Congo.

Operation Menace

The Free French began planning a descent on Dakar with 2,700 men drawn from de Gaulle’s small army, embarked in two Dutch liners, Pennland and Westernland. De Gaulle himself made his headquarters on the Westernland. On August 8, the day after the Germans began the Battle of Britain, the British agreed to support the invasion with the Royal Navy and 4,000 Royal Marines in four battalions. The Marines were preparing for a possible assault on the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands and the Azores to gain bases to use against U-boats, but the British War Committee was unsure about the idea of invading territory held by “Britain’s oldest ally.” So the British would back Operation Menace, the code-name for the attack on Dakar.

The Royal Marines were packed into four mechanical transport ships, and Maj. Gen. Noel Irwin was appointed boss of the land force. Admiral John Cunningham was chosen to head the naval force, which consisted of the tough aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the old battleship Resolution, the slightly faster battleship Barham, the cruisers Devonshire and Fiji, 16 destroyers, and two sloops. Free France provided three sloops, a patrol vessel, and two Luciole touring aircraft for Ark Royal.

The Allied plan was to sail to Dakar and launch the Luciole touring planes, loaded with emissaries from de Gaulle. They would bring a message urging the Vichy leadership to join with de Gaulle. If all went well, Dakar could be taken without firing a shot.

“To Dakar!”

As usual before an amphibious assault, all was confusion. French officers ignored security by toasting, “To Dakar!” in Liverpool pubs before embarking. Loading of the ships was chaotic: motor transport, miscellaneous stores, and four tons of ammunition were not loaded, even though the ships were packed to capacity. Nobody made a plan of storage for the equipment on board, and nobody told the Liverpool and Greenock port authorities what supplies had the highest priority for unloading, so nobody knew where the supplies were loaded on each ship. The ships were barely seaworthy. Irwin’s headquarters had problems, too. His staff had only one typewriter upon which to make the required 200 copies of the 140-page command directions.

Once at sea, the ships could communicate only with signal lamp because of a shortage of trained expert wireless operators. Irwin himself lacked a headquarters ship and had to embark on the battleship Barham. The result was that at one point he was heading north at 25 knots while his forces were heading south at 12 knots. On another occasion, he was heading at five knots to the advance base while his ships sailed ahead of him at 12 knots.

Nor were the invaders well prepared. The French troops were completely untrained in amphibious warfare. The invaders had only 18 landing craft for the entire operation. Their air cover consisted of Ark Royal’s 25 Swordfish biplane torpedo-bombers and 20 Blackburn Skua fighters, neither of which were the equal of the American-made Hawk 75 fighters and A-22 bombers the French fielded.

The French defenders would be tough, too. Admiral Landriau had been sent down from Vichy to put them into shape, and he had imposed order and efficiency. In addition to Richelieu’s guns, the French fielded about two understrength brigades and a number of coastal artillery pieces, some of them at Fort Gorée, an island bastion infamous as the transshipment point for generations of slaves to the Western Hemisphere for three centuries. But they were far from home, and their nation had just been defeated by a major power. British determination and Free French ferocity could overcome these obstacles.

Force Y Complicates the Expedition

But Vichy was not idle. They greeted the secession of Equatorial Africa with firmness, dispatching Force Y, consisting of three light cruisers, the Georges Leygues, Montcalm, and Gloire, from France to deal with the insurrection. Also en route to the Congo from Casablanca was the light cruiser Primauguet and an escorting tanker, to fuel Force Y.

To reduce tension, the British had chosen a policy of not interfering with Vichy ships on purely French missions. So when the three cruisers headed for Gibraltar, there were no plans in hand to stop them. Worse, the British boss at Gibraltar, Admiral Sir Dudley North, had no knowledge of the plans to invade Dakar. When the three cruisers sailed past Gibraltar in the early hours of September 11, he took no action to stop them. By 4:30 pm, however, London and Vice Admiral Sir James F. Somerville, who commanded Force H based at Gibraltar, reacted. The battle cruiser HMS Renown went to sea to try to prevent the French ships from at least reaching Dakar. Too late. That evening, the French ships were refueling in Casablanca. They left before daylight, heading south.

Meanwhile, the Dakar expedition weighed anchor on August 31, sailing from the Clyde, Liverpool, and Scapa Flow. Cunningham flew his flag on the cruiser Devonshire and moved to Barham. Along with the force were six destroyers from Force H and the boom defense vessel Quannet from the South Atlantic squadron. The heavy cruiser Cumberland was already on station off Dakar.

On the first day, the German submarine U-32 put a torpedo into the side of HMS Fiji just west of the Hebrides, making her a dockyard case. The British, now short a cruiser, sent Fiji back to the Clyde and replaced her with HMAS Australia, attached to the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow, and she sailed from the Clyde for Sierra Leone on September 6, to relieve Cumberland on patrol off Dakar, reaching it at 8:20 am on September 19.

Twenty minutes later, Australia spotted the three French cruisers coming toward it, heading southeast. Australia followed the trio all day, until she lost them that evening. Australia’s captain, R.R. Stewart, figured the French were headed for Dakar and plotted an intercept course. Sure enough, Stewart came up on a darkened ship, which turned out to be Gloire, moving slowly due to an engine breakdown.

A game of signal-lamp diplomacy ensued, with those on the Australia convincing the Vichy French to sail back to Casablanca, signaling, “I know how difficult the situation is.”

But Admiral Bourragué, commanding the French cruisers, turned his other two ships about, cranked up to a snappy 30 knots, and sailed in to Dakar on September 20.

The two additional cruisers at Dakar tipped the balance for M. Boisson, the Vichy governor. He would fight anyone who attacked his colony. It also irritated Darlan, boss of what was left of the Vichy Navy, who hated Britain. He fired Bourragué for not fighting back against the British or heading on to the Congo.

It turned out that Borragué could not get to the Congo. The lead ship, cruiser Primauguet, ran into the light cruiser HMS Neptune in the Gulf of Guinea. Neptune convinced the French to head back to Dakar, and that ended Darlan’s porous plans to overawe the Congo into ending its secession.

Executing Plan B

The Vichy French moves unnerved London, which suggested de Gaulle’s force return and Operation Menace be called off. De Gaulle argued to his British seaborne colleagues, Cunningham and Irwin, that to withdraw would only hand Vichy a propaganda victory. Churchill agreed. Operation Menace went on.

But while Primauguet and her tanker turned about, the British fleet arrived off Dakar on September 23, to find the French colony fogged in. That shot down Churchill’s plans of massing a huge (by local standards) fleet off Dakar to overawe the French leadership. Instead, it was time for Plan B, which consisted of Ark Royal launching the two Luciole aircraft off her flight deck with four Free French airmen aboard to make a surprise landing at the airfield at Ouakam, three miles from the town. Meanwhile, a Free French motor launch with Lt. Cmdr. d’Argenlieu aboard would sail into Dakar to deliver a personal message from de Gaulle to Boisson. While this went on, British planes would drop leaflets on the town. De Gaulle would also broadcast on radio. With luck, the Vichy French would give in.

The first part went fine. The airmen landed at Ouakam and found the commanding officer waiting to greet them. The airmen promptly took the commanding officer prisoner and laid out a “success” signal for Ark Royal’s planes. But the Vichy guard was not impressed and took the intruders prisoner in short order.

Next up, d’Argenlieu. He and three other officers, Major Gotscho, Captains Bécourt-Foch and Perrin, and Sub-Lieutenant Porgés sailed into the port in a motorboat from one of the two Free French sloops in the attack force and stepped ashore, asking to meet with Boisson. Instead, Admiral Landriau, the top French officer on the scene, showed up, having heard de Gaulle’s speech. He ordered d’Argenlieu and his cronies arrested. The Free Frenchmen jumped back in their motor boats as the Vichy guard opened up with their machine guns. D’Argenlieu and Perrin were seriously wounded, but the two boats made off into the fog and met up with their sloop at the harbor entrance, bringing the bad news as Richelieu’s secondary guns hurled parting shots at them.

De Gaulle’s speech had told his countrymen that if they gave in the Royal Navy would not open fire, but with the failure of diplomacy, de Gaulle made another broadcast, warning that the Royal Navy would train its guns on Dakar if the defenders did not surrender. The Vichy response was gunfire from the coastal batteries, now manned by naval gunners instead of colonial soldiers of questionable reliability. Tugs maneuvered the Richelieu to an angle where it could more effectively fire its two forward-mounted 15-inch turrets. Clearly, neither Vichy’s rulers at Dakar nor their rank and file had any love for de Gaulle or the British.

The Battle at Sea

At the same time, two of the four Vichy submarines at Dakar, Persée and Ajax, put to sea to wreak havoc among the attackers. The British destroyers Foresight and Inglefield spotted them and gave pursuit. Both tin cans came under shore battery fire and took hits. The Persée showed foolhardy courage, trying to make a surface torpedo attack on the huge Barham. British gunfire sent the submarine to the bottom.

Cunningham signaled the Vichyites: “Why are you firing on me? I am not firing on you.” The Vichy men answered, “Retire to 20 miles distance.” The British responded with gunfire of their own.

At a range of less than 6,000 yards, the Barham opened fire on the French forts with her 15-inch guns, but some of the “overs” hit the town, killing civilians, which added to the bad Vichy temper. The Vichyites fired back, hitting Foresight and putting a 9.4-inch shell into Cumberland’s hull, seriously damaging the cruiser. At 11:15, Cunningham pulled his ships out of range. From the desultory fighting so far, de Gaulle did not believe the Vichy men intended to do anything but put up a brief fight to protect honor, then surrender. But clearly there was no way to storm the harbor without a greater battle, which could inflame passions in Dakar or worse, Vichy, and bring the otherwise inert and semineutral nation back into the war as a German ally. The British were ready to assault the port but knew the casualties on both sides would be terrific.

“Up to now, we have not made an all-out attack on Dakar,” de Gaulle said. “The attempt to enter the harbor peaceably has failed. Bombardment will decide nothing. Lastly, a landing against opposition and an assault on the fortifications would lead to a pitched battle, which for my part, I desire to avoid and of which, as you yourselves indicate, the issue would be very doubtful. We must, therefore, for the moment, give up the idea of taking Dakar. I propose to Admiral Cunningham that he should announce that he is stopping the bombardment at the request of General de Gaulle. But the blockade must be maintained in order not to allow the ships now at Dakar their liberty of action. Next, we shall have to prepare a fresh attempt by marching against the place by land, after disembarking at undefended or lightly defended points, for instance at St. Louis. In any case, and whatever happens, Free France will continue.” The British agreed.

While Cunningham and de Gaulle plotted their next move, all hands ate lunch, bully beef stew on HMAS Australia, which a sailor pronounced “Rotten!” At the same time, Boisson signaled the British, saying that all landings would be opposed.

The British and the Gaullists decided to try again, this time landing Free French Marines at Rufisque, a small port on the far side of the bay, 10 miles east of Dakar. The port was too shallow to allow the British to unload their Royal Marines and their heavy equipment from transports, so the two French sloops would land 180 Fusiliers Marins. Perhaps their appearance would convince the Vichyites to surrender.

To do so, the British and Free French ships had to regroup—they were getting lost in the mist.

But at 4 pm, the French destroyer L’Audacieux steamed out, battle flags flying, near Gorée Island. The British destroyers Fury and Greyhound steamed in to attack her, joined by HMAS Australia, which spotted the Frenchman at 4:26 and opened fire with three-gun 8-inch salvos a minute later. The third salvo dismasted the enemy, and the fourth set L’Audacieux on fire forward. Blazing fore and aft, the French destroyer was clearly disabled, and Australia withdrew while the blazing French ship drifted ashore, more than 80 of her crew dead.

At 5:30 pm, the two Free French sloops sailed into Rufisque harbor and put a few men ashore. The Vichyites replied with 4-inch gunfire from a shore battery, while Senegalese troops treated the Marines to machine-gun fire. The Marines had to be reembarked and withdrawn—sharp eyes on the Westernland saw the Georges Leygues and Montcalm heading for Rufisque.

The British steamed into the mist and out of range for the night to treat their wounds and plot their next move. Clearly the Vichy French were fighting, and another bloody battle between British and French forces was developing. Somehow, Dakar had to be taken without heating the battle up further.

“We Must Go On to the End. Stop at Nothing!”

The commanders could call off the operation, but at 9 pm Cunningham received a message from Winston Churchill himself, saying, “Having begun, we must go on to the end. Stop at nothing!” Fine rhetoric, but what to do? Cunningham, Irwin, and de Gaulle conferred again, and at 11:45 pm they sent another message to Boisson, Landriau, and the inhabitants of Dakar.

This time the British told them that the Allies had to seize Dakar at all costs and demanded an acceptance of their terms by 6 am on the 24th. Then everybody waited for the Vichy answer. It came at 4 am: Boisson rejected the British demand. He would defend Dakar to the end.

At dawn, Cunningham’s two battleships and two cruisers opened fire on Dakar from eight miles out, joined by Ark Royal’s aircraft, which tried to plaster the forts and Richelieu, as well as the two Force Y cruisers.

The British had no luck. The French cruisers maneuvered behind their booms and avoided the torpedoes. The British lost three Swordfish. At 8:30 am, the French submarine Ajax tried to attack the British battleships on the surface, and the destroyer Fortune sank the Ajax. Barham and Resolution traded salvos with the forts and Richelieu for 40 minutes, by which point fog and smoke rendered the French fully covered.

At this point, the French Air Force materialized, with Glenn Martin bombers trying to make high-level attacks to no avail. After waiting for the smoke to dissipate, the British tried again, shelling the French for half an hour, with Barham suffering four hits from French fire.

The British fired more than 400 rounds of 15-inch ammunition and completely failed to silence the shore batteries, while causing more civilian casualties in the town. The smaller French batteries, which were damaging the British destroyers, could not be silenced. The Fleet Air Arm was facing more opposition.

Final Withdrawal

There seemed no way to get the troops ashore without a massive battle, which was just the thing the British commanders did not want. Late that afternoon, de Gaulle met with Cunningham and Irwin aboard the Barham. De Gaulle had to admit that he had underestimated both the Vichy defenses and Vichy resolve. A British landing would only expand the war and make things worse. De Gaulle had two ideas: either land his troops at Bathurst for training and take Dakar later by land or disembark the French troops at a lightly held area and march on Dakar. Either way, he could not risk the political liability of British troops fighting a battle against French troops—it would only drive Vichy into Hitler’s arms.

Next morning, the fog lifted and visibility was better. The battleships steamed in, White Ensigns flying, to resume bombarding the port, while the two cruisers headed for Gorée Bay to take on Force Y. At 9 am, the Richelieu opened fire on the Barham at a range of 23,000 yards. The two dreadnoughts traded salvos, and as the British ships turned to the bombardment course the last French submarine, Bévéziers, appeared and fired four torpedoes at Resolution, scoring a hit amidships.

The old battleship suffered serious flooding and slowed to a halt. Cunningham ordered two destroyers to cover Resolution with a smokescreen. Meanwhile, Barham engaged Richelieu, Devonshire fired at Fort Manuel, and Australia took on Force Y. The French shot back accurately, hitting Barham once and Australia twice. The French 6-inch hits on Australia caused no casualties and only slight structural damage in the wardroom and an engine room store. At 9:16, the two cruisers withdrew, and at that moment French antiaircraft guns blasted the Australia’s spotter Walrus seaplane, causing the Australia’s only casualties of the battle, the deaths of the plane’s crew: Flight Lieutenant G. J.I. Clarke of the Royal Australian Air Force and Lt. Cmdr. F.K. Fogarty and Petty Officer Telegraphist C.K. Bunnett, both of the Royal Australian Navy.

At 9:20 am, all British ships ceased fire and withdrew on a southern course, under cover from Ark Royal’s fighters. Resolution was now doing a bare 10 knots with a 12-degree list, which made her a target for French bombers, but she avoided further damage.

On his flag bridge, Cunningham did the sums: all four of his heavy ships had been damaged. Further attacks could lead to unacceptable losses on his side and Vichy French alliance with Hitler on the other. Cunningham decided to withdraw the entire force to Freetown, with Barham towing Resolution home. Dakar remained under Vichy control.

“The Days Which Followed Were Cruel For Me”

De Gaulle was devastated. “The days which followed were cruel for me,” he wrote later. “I went through what a man must feel when an earthquake shakes his house brutally and he receives on his head the rain of tiles falling from the roof.”

Nothing had gone right for the British. Intelligence was lamentable, planning slipshod. British gunnery had accomplished nothing against the defenses, and neither the diplomatic landings nor the Marine assaults had accomplished anything. German propaganda had a field day with British ineptitude, and the Australian government complained to Churchill about learning of the use of their heavy cruiser only after the battle was over.

It was left to Churchill to smooth over ruffled Australian feelings, and he did so with a letter that blamed the French cruisers, the fog, and the shortage of British ships and men at a time of great peril at home and abroad. The Australians showed sympathy and support for Churchill’s position.

Meanwhile, officers on the spot and historians after the fact—Churchill among them—assessed blame. Part of the failure was a systemic issue. The assault was Britain’s second amphibious operation of the war (the Norwegian disaster being the first), and little had changed for the Royal Navy since its last big amphibious campaign at Gallipoli in World War I—another disaster. Had the British force gone in, it may have well been undone by poor logistical loading as much as by the determined French defense.

But there was a good reason for the British ineptitude. Most of the paraphernalia of the later Allied invasions had not even been invented yet. Amphibious landing craft, coordinated air observation techniques, fire control, even weather forecasting, were all marvels yet to come. While the British fumbled about at Dakar, the Germans, by way of comparison, were planning their invasion of England, which called for thousands of horses in the first wave. Amphibious operations needed a lot more planning and expertise before they could achieve success.

Other problems came from the difficult political situation. The British were eager to make Dakar a key base of operations, both to fight U-boats and to rally the Free French cause, but were reluctant to fight hard with Vichy, fearing that Pétain and his cronies would join Hitler in the invasion of England that was a real and hourly fear in London. Nor did de Gaulle have anywhere near enough weaponry and men to impose his will on the Dakar leaders.

“Miscalculation, Confusion, Timidity, and Muddle”

In his memoirs, Churchill noted that the weather for the time of year at Dakar usually called for sunny skies, but the heavy fog was a surprise. Other Admiralty officials claimed that was not so. Churchill also noted that the British and Gaullists had underestimated Vichy resolve to hold Dakar and overestimated their small force’s ability to compel the Vichy defenses to surrender. The British would not make that mistake again in dealing with Vichy, using heavy forces to overwhelm Vichy defenses in Syria and Madagascar later in the war.

“No blame attached to the British naval and military commanders,” Churchill also wrote, and he pointed out that Vichy did not follow up by declaring war on Britain; it merely launched a pair of air raids from Morocco on the British base at Gibraltar. “The French aviators did not seem to have their hearts in the business, and most of the bombs fell in the sea,” Churchill wrote of the two strikes. “Some damage was done, but there were very few casualties. Our AA batteries shot down three aircraft. Fighting at Dakar having ended in a Vichy success, the incident was tacitly treated as ‘quits.’”

To the world, Churchill wrote, the affairs “seemed a glaring example of miscalculation, confusion, timidity, and muddle.” He was right. American military attaché General Raymond Lee wrote acidly, “Dakar does not sound like any resoundingly successful feat of arms.”

The Free French Movement Stays Alive

Still, some things were gained. The British loss of prestige was minor compared to their heroic defense of the British Isles that summer. Three French submarines and a destroyer were punched out. The damage to the British ships was all reparable, and the Free French colonies stayed loyal to de Gaulle. Richelieu remained immobile at Dakar, and the two cruisers stayed with her in a similar plight. Indeed, a barrel explosion wrecked one of Richelieu’s guns during the battle.

Ultimately, Dakar would go over to the Allied side in November 1942, after Operation Torch and the German occupation of Vichy France. With American assistance, Richelieu would get under way and sail to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to gain a new 15-inch gun, a complete modern electronics suite, and additional antiaircraft guns, while having hundreds of barnacles removed from her bottom. Richelieu would serve in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, shelling German and Japanese defenders, while the two light cruisers steamed into battle against Hitler on D-Day in Normandy and again in the invasion of southern France.

De Gaulle’s determination to fight kept him at the head of the Free French movement. Within two weeks, he went ashore at Libreville, the capital of Gabon, and by November, through his own personality and local resources, won control of the whole of French Equatorial Africa.

Still, the battle had been a close-run thing. Supposedly, when Cunningham withdrew his ships for the last time, Boisson had been writing out a message of surrender as his forts were nearly out of ammunition. However, that story is questioned by historians.

These thoughts were far from the minds of the Allied ships as they turned for Greenock, the Clyde, or the Congo. On the damaged ships, crewmen repaired shell holes. On a troopship, Royal Marine Lieutenant Evelyn Waugh started batting out a rough draft of what would become his novel, Put Out More Flags. De Gaulle plotted his next moves.

When HMAS Australia returned to Greenock, the crew got some leave, and Captain Stewart wrote in his log the only piece of good news from the whole affair: that the conduct of his officers and men under fire had been outstanding, and “a most noticeable ship spirit has now been born which gives me every confidence for the future of HMAS Australia.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments