Phil Zimmer

Adolf Galland stroked his well- groomed mustache as he strode confidentially toward his distinctive Messerschmitt Me-109E with its brightly painted fuselage art featuring Mickey Mouse smoking a cigar and wielding a hatchet.

“The British are coming,” he muttered to himself as he took off to intercept a force of sturdy, snub-nosed Bristol Blenheim bombers raiding Saint Omer. The bombers were accompanied by some 50 Spitfires and Hurricanes flying escort over northwestern France on that day, June 21, 1941.

Eight minutes after takeoff, Galland sent one Blenheim crashing to earth and a second one down in flames a mere four minutes later. Those were victories 68 and 69 for the dashing pilot who was a near “look-alike” to movie idol Errol Flynn. But then, the accompanying Spitfires caught the 29-year-old pilot in their crosshairs, shooting up his fighter and sending it into a crash landing on the nearby airfield at Calais-Marck.

He escaped unharmed and within a half an hour an Me-108 swooped down and carried him back to his squadron. The day was not done for the fearless pilot, though, because just three hours later, he was back in the air and sending a Spitfire down in flames. That gave him a third victory for the day on the eve of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union at the other side of the European continent.

Lieutenant Galland was exhilarated about his victories that day, but suddenly “all hell broke loose,” as he recalled in his memoirs. Cannon fire from an enemy plane ripped through his wings, and something hit his head and arm. His fuel tank and radiator leaked badly and the right side of his fuselage had been ripped away. The engine cut out, but the plane still somehow flew, and at 18,000 feet he began an attempt to glide back to base.

That was when the worst happened. The plane’s fuel tank exploded and the whole fuselage became engulfed in flames, with burning fuel quickly pouring into his cockpit.

He instinctively grabbed for the cockpit canopy release, but it was jammed tight. Thinking quickly, he snapped his belt free and tried again to force the canopy open, desperately pushing his whole body up against it as the flames licked around him.

The canopy finally gave way to his desperate efforts, but he was not completely thrown free from his burning coffin. Galland’s parachute was caught on the flaming plane, dragging him toward certain death. He found his arm wrapped around the plane’s aerial mast as he tugged and pushed with all his energy before finally breaking free. He tumbled and managed to open his parachute and then slowly floated to earth.

“I should have landed in the Forest of Boulogne like a monkey on a tree,” he recalled, “but the parachute only brushed a poplar and then folded up” as he came down in a soft, boggy meadow. Cautious French peasants collected him up and took him to a farmhouse, where he was retrieved by a German construction crew that drove him back to his base at Audembert. After a brief visit to a nearby naval hospital where he was checked over and patched up, the fortunate flyer was cleared for general ground-based duties for the time being.

Initially, the grounding after being shot down twice in one day did not bother Galland too much because his injuries, after all, had limited his mobility. Once he could get about on a cane, the hobbling officer managed to get two new aircraft and conduct some gun testing. The irrepressible pilot then took the next step in recovery, taking it “for granted that the grounding order only applied to combat flying.”

On a flight on July 2, just days after his near-death experience, he had another nasty encounter with a Spitfire. He was supposedly on a “test flight” when he led with his entire wing against a gaggle of Blenheims, escorted by Spitfires, conducting a raid over Saint Omer. He led the attack on the intruders, diving through the fighters to close in on the leading Blenheim. He fired at a distance of about 200 yards as he closed to ramming distance.

“Pieces of metal and other parts broke away from the [bomber’s] fuselage and the right engine” as it went up in smoke. Then a Spitfire jumped Galland as he was chasing another fighter, shattering the German’s cockpit with his gunfire and causing another head wound. Losing a substantial amount of blood and afraid of blacking out, he succeeded with great effort in shaking off the attacker and landed safely.

His life had been spared that day by his leading rigger, Sergeant Meyer, who had quietly fitted additional armor plating near the top of his cockpit. “Without that armor plating, nothing would have remained” of his head because of the Spitfire’s deadly cannon fire.

The grateful Galland saw to it that Meyer got special leave and 100 Reichsmarks. “I value my head that much,” he aptly noted.

At this point in the war, the British had turned back the Germans in the Battle of Britain and were now escalating their attacks on the Continent just as the Nazis were massing in the East for their fateful lunge into the Soviet Union.

The next few years would be fateful—and bloody—for all involved, especially for men like Galland who took to the skies in ongoing efforts to affect the course of the war through their singular efforts, often thousands of feet above the earth.

The charismatic Galland was one of the fortunate ones in the Luftwaffe. He flew a total of 705 combat missions, survived being shot down four times, and earned 104 aerial victories against the Western Allies, all while surviving several intrigues, many with the head of the Luftwaffe, Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, and a tangle or two with Hitler as well.

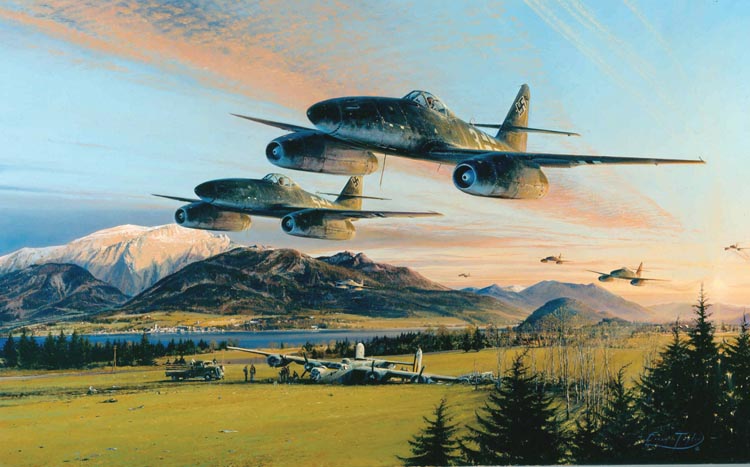

Galland, who had a fondness for cigars and brandy, began the war as a first lieutenant and ended it as a lieutenant general commanding an Me-262 jet fighter unit. In November 1941, he was named General of Fighter Pilots, making him at age 30 the youngest general in the German military. It was a position he held for nearly three turbulent years.

By mid-summer 1944, he had been reassigned from that noncombat position to command the jet fighter unit following a disagreement with Hitler and others over Galland’s outspoken need for more fighter jets—not bombers—to protect the homeland.

“Dolfo” Galland was born on March 19, 1912, in Westphalia, the second of four sons of a land manager. He showed an early interest in aerodynamics, flying hand-built gliders as a youngster. In 1932, he trained at an aviation school run by Lufthansa, the German airline company, and the following year he entered what would become the Luftwaffe.

He survived two training crashes in the early 1930s. One resulted in a three-day coma, a fractured skull, a broken nose, and a damaged left eye that was to plague him throughout his life. The eye injury prompted the determined and resilient Galland to memorize the eye chart to pass the medical exam.

Galland was a member of Germany’s Condor Legion that participated in the Spanish Civil War, where he flew Heinkel He-51 biplanes in ground-attack missions in support of the Nationalists. His 300 missions provided invaluable experience and he was awarded the Spanish Cross in gold and diamonds for his role.

Just prior to World War II, Galland was promoted to captain and he later flew 50 ground-attack missions in a biplane against Polish forces, receiving the Iron Cross Second Class at the end of that campaign. With a wink and a nod, he managed to swing over to the fighter arm of the Luftwaffe in time for the campaign in France, where he rolled up his first 14 victories and became the third fighter pilot to receive the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross medal.

He participated in the Battle of Britain, and by the end of 1940 Galland had notched 58 kills. By the following year, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and made commander of one of only two German fighter wings in France.

His bravery and dynamic leadership made him a standout, and in November 1941 Göring named him General of the Fighter Arm, replacing Werner “Vati” Mölders, who had died in a flight mishap on the way to the funeral of his predecessor, Ernst Udet, who had shot himself presumably because of heavy criticism laid at his doorstep by none other than Göring. To cover up the embarrassing episode, the German people were told that Udet had died in an accident while testing a new plane.

Mölders, who had 115 victories to his credit, died just five days after Udet. The country was shocked by the nearly back-to-back deaths of its two national heroes. Mölders, like Galland, was one of only a few pilots to hold the prestigious Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds.

It was at Mölders’ funeral at the Invaliden Cemetery in Berlin that Göring beckoned Galland over and named him successor to the deceased.

“I was never in my life happy at a desk. My squadron meant everything to me. I hated everything to do with staff. I was now going to be one of those ‘brass hats’ for whom we had also used the most derogatory terms,” admitted Galland, who cavalierly used one of his girlfriend’s garters to hang his Knight’s Cross around his neck.

The outspoken Galland created ripples in the Nazi hierarchy almost immediately. He opposed, for example, the decision to dig into the Luftwaffe’s training reserves to produce the flying fighter units that Hitler deemed necessary for the spring 1942 offensive in the Soviet Union.

Galland argued that the only aerial foe to be taken seriously at that point was in the West, and there was a greater need for fighter pilots there, especially because the vanguard of the U.S. Army Air Forces had started to make its buildup in England. There was also a need to step up aircraft production, especially fighters, he strenuously argued.

Training and increased pilot recruitment were especially needed in addition to increased production. “If you reduce them now instead of forcing them up, you are sawing off the branch on which we are sitting,” he told anyone who would listen.

They did not. Instead, they acquiesced to Hitler’s demands that full efforts be devoted immediately to subduing the Red Bear that had been driven back on its haunches in Germany’s initial thrust. Galland believed Hitler was betting on a quick takedown in the East. Then the Luftwaffe and related Nazi resources could be realigned against the Western Allies.

Although he hated deskwork, the newly reassigned fighter pilot did an admirable job in planning and coordinating fighter cover for the boldly executed “Channel Dash” in early 1942 that enabled the prized battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst—along with the cruiser Prinz Eugen—to safely escape from the French port of Brest, where they were being pelted by British air attacks.

Galland memorably described the German ships in Brest as “flytraps,” diverting British attacking strength away from the Reich. The Brits had made more than 295 attacks on the docked ships and had lost 43 planes and 247 airmen, according to Galland. Their aerial efforts were not without effect: Gneisenau was hit twice and Scharnhorst struck very heavily once, but both were repaired.

The ships needed to be freed for further duty, especially in light of the planned invasion of Norway. Galland demonstrated his cool thinking in working up plans for the Luftwaffe’s role in a daring daytime dash through the Channel right under the eyes of the watchful British. He worked closely and under the tightest security with the German Navy.

Galland, for his part, needed to provide a well-thought-out and rather complicated system of overlapping fighter protection involving more than 300 planes and to make those detailed preparations without arousing British suspicions. Added to the defensive mix were seven covering destroyers and several speedy E-boats.

The dash commenced in the dark hours of February 11, 1942, and when dawn broke, the flotilla was off the Cotentin Peninsula. Strict radio silence was maintained initially by the Navy, as well as by the fighter pilots who skimmed the waves to avoid radar detection.

For two full hours of daylight, the force spun forward through the Channel, where no substantial British enemy force had dared to go since the 17th century. They were then spotted by a British fighter, but it was nearly another hour before the startled Brits took the report seriously and responded. The Germans then kicked in their radar interference and false radar signals that indicated the British homeland faced large numbers of incoming enemy formations.

The deceptions worked, throwing the Brits off their game for a time. But soon, British coastal fire opened up on Prinz Eugen, and torpedo boats from both forces began trading shots. Scharnhorst then began taking damaging artillery fire and developed engine difficulties. Six slow-moving Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes, escorted by Spitfires, entered the fray. Galland’s fighter planes tangled with the attackers, and the torpedo attack planes were knocked out of the sky with assistance from German naval fire.

The action lessened but did not cease as night fell, with British aircraft dropping additional mines. Both Gneisenau and Scharnhorst hit mines during the night, but all three ships managed to reach safety in German waters by morning.

The Germans publicly claimed some 60 British aircraft destroyed and a British destroyer set aflame in the engagement for the loss of only one torpedo boat, a handful of aircraft, and no mention of the relatively light damage to two of its capital ships.

The fact remains that the “Channel Dash,” conducted within range of the Home Fleet and within one of the narrowest straits in the world, was a win for the Germans and it caused consternation among the British. Not since 1690 had England seen a strong enemy force pass through that area. (Read more on the Channel Dash, here.)

The daring daylight dash under heavy and overlapping German fighter cover proved to be a feather in Galland’s cap. He proved he could handle innovative and detailed administrative duties when he set his mind to it, but throughout his career, he often proved unable to hold his tongue when it came to others above him who held differing views.

In August 1940, for example, Göring visited a Luftwaffe airfield during the Battle of Britain and verbally abused his fighter pilots for failing to defeat the British. Turning to Lieutenant Galland, he asked what was needed to finish the job. “I would like Spitfires for my group,” Galland reportedly shot back, leaving the red-faced and flustered Göring speechless.

One of Galland’s biggest issues with Hitler occurred over the Führer’s demand that the successful fast-flying Me-262 jet be hastily reconfigured as a bomber and used in retaliatory raids against the Allies. That was the argument that got the high-scoring ace reassigned from his desk job late in the war to eventually command an Me-262 fighter unit near Munich. He performed admirably, developing new tactics for the jet fighters and putting newly developed air-to-air rockets to good use against seemingly endless armadas of incoming Allied bombers covered by Mustang and Thunderbolt fighters.

Galland’s frustration and antipathy toward his superiors, especially Göring, ran deep. His efforts as early as 1942 to “explain the seriousness of the Luftwaffe’s situation to the High Command miscarried. After the failure of our air offensive on England, they embarked upon a path of criminal carelessness. They did not want to see the danger, because they would have had to admit their many omissions and neglects.”

“Unpleasant reminders,” he added, perhaps referring to himself, “were regarded as a great nuisance.”

Interestingly, it was Galland’s frankness and directness that made him such an asset when captured in May 1945 by American forces. He proved open and helpful, and his interrogation reports provided straightforward insights and assessments of German tactics, strategies, and military capabilities. Even today, more than seven decades after the bitter war, one is taken aback by the objective observations and insights that Galland provided.

The examples are numerous in his postwar comments, including an October 15, 1945, interrogation in which he stated, “Göring often appeared in operational units and made spot promotions of NCOs to officers for little or no reason, thereby burdening the Luftwaffe with some unqualified officers.”

In the same interview, he noted that fighter pilots were not held in high esteem by the upper levels of the Luftwaffe, which was composed largely of bombardment personnel. His assessments of Allied fighters and their strategies also proved insightful, providing new ways to train pilots and arm planes for future conflicts.

Galland also produced German statistics to his captors from early in the war that showed that, when a larger number of attacking planes participated in a raid, the percentage of losses decreased. Interestingly, as Allied raiding strength increased as the war progressed, the percentage of Allied losses indeed decreased.

Taken captive after the war, he was released by the Americans in 1947, after which the energetic Galland went on to a successful career as an aviation consultant, first serving seven years with the Argentine Air Force before returning to Germany. He passed away quietly in Germany on February 9, 1996.