By David Alan Johnson

As soon as he arrived on the bridge of the submarine USS Dace, Lt. Cmdr. Rafael C. Benitez, the vessel’s executive officer, was handed a dispatch from USS Darter, Dace’s sister: “Fast ships on northeasterly course.” Benitez knew exactly what it meant. “Fast ships” was shorthand for enemy warships, as opposed to the marus, the slow and bulky Japanese cargo vessels. Dace had already torpedoed two marus in a Japanese convoy on October 12, 1944, but now would be pursuing a much larger prey.

“A Beautiful Picture” of the Enemy Fleet

At 12:16 am on October 23, the enemy fleet made its presence known as a huge blip on Darter’s radar screen. At first, the radar operator thought the contact was a rain storm at the southern entrance to the Palawan Passage near the Philippine Islands, but he very quickly realized what the radar had actually picked up. As soon as he read Darter’s dispatch, Commander Bladen D. Claggett, Dace’s captain, ordered a change of course to intercept at full speed.

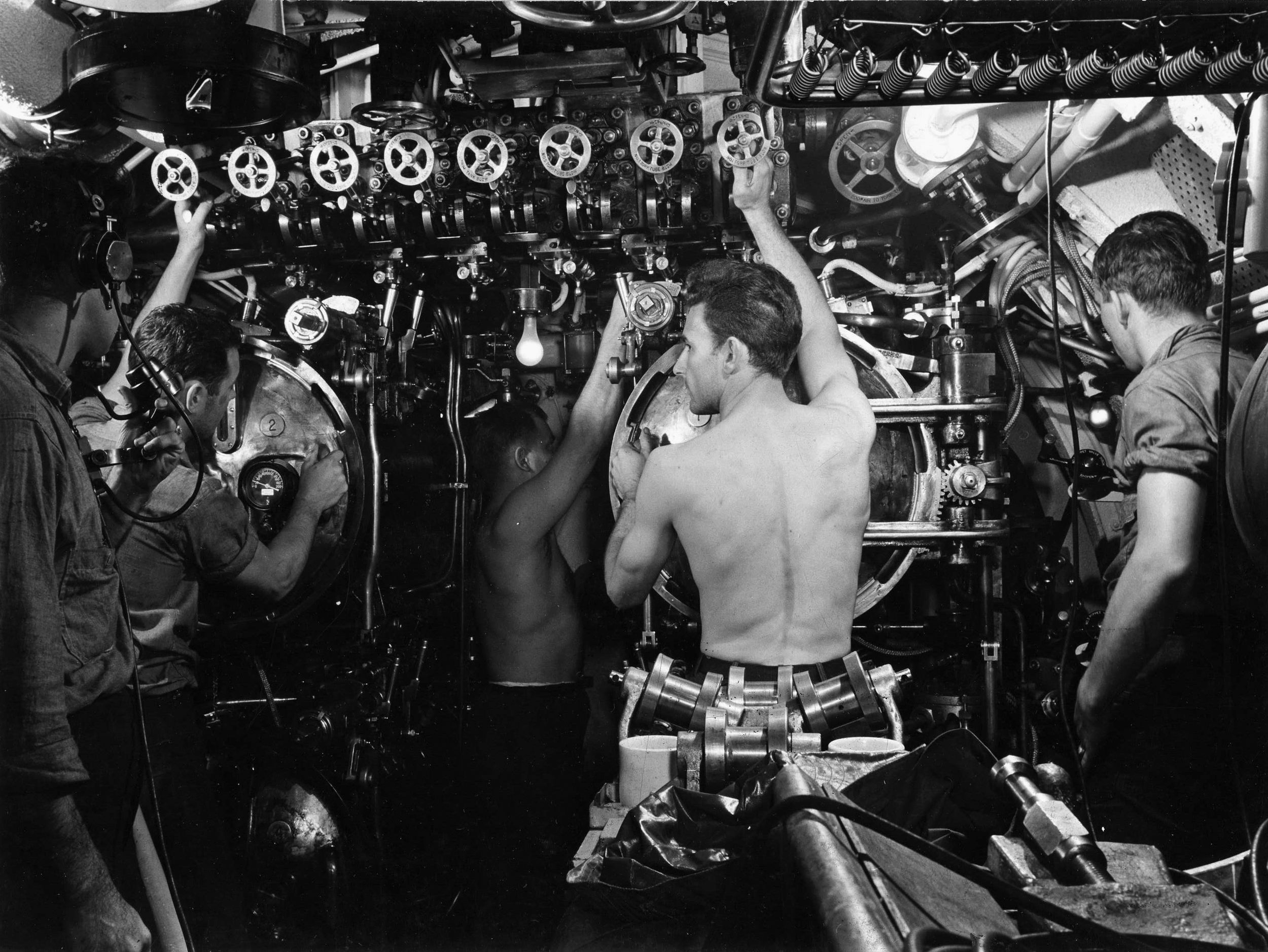

Both submarines closed with the enemy at maximum speed on the surface, using diesel fuel at a prodigious rate. A U.S. Navy fleet submarine was actually a surface vessel that had the ability to run submerged for limited periods of time. “Minutes later,” Benitez recalled, “the radar scope gave us a beautiful picture of many ships, and once again we knew that this was no ordinary convoy.”

Dace’s radar “conked out,” in the words of the boat’s radar operator, for about half an hour. But Darter remained in contact with the enemy, as well as with Dace. The two submarines were close enough that the bridge watches were able to talk to each other by megaphone. Darter also began sending reports of the enemy contact to Rear Adm. Ralph. W. Christie at Submarines Southwest Pacific. Admiral Christie relayed this information to Admiral William F. Halsey, commander of the U.S. Third Fleet at sea off the Philippines. When Dace’s radar was repaired, the operator could make out two columns of enemy warships—11 heavy ships and six destroyers. The task force was steaming northeast at about 16 knots with no picket destroyers running ahead of the main force.

All through the early morning hours, Darter continued sending updated reports of the enemy’s course and speed. Commander David H. McClintock, Darter’s captain, even supplied the enemy’s zigzag pattern. The Japanese obviously suspected that American submarines were in the area, which made the absence of picket destroyers a curious omission. The plan was for the two submarines to track the enemy through the Palawan Passage, in the 25-mile-wide channel formed by uncharted reefs aptly called the Dangerous Ground. At dawn, after making visual contact, they would attack with torpedoes.

“The Most Significant Reports of the Pacific War”

Darter and Dace had intercepted the main body of the Japanese Navy’s First Striking Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Takao Kurita. Admiral Kurita’s task force was entering Palawan Passage on its way to Leyte Gulf to attack General Douglas MacArthur’s landings on the island of Leyte. A massive American flotilla of 420 transports escorted by 157 warships had put MacArthur’s U.S. Sixth Army ashore at Leyte on October 20. MacArthur had been given the assignment of “liberating” the Philippines from two and a half years of Japanese domination. Kurita and a smaller force under Vice Adm. Teiji Nishimura were sent to execute a pincer movement against the American amphibious forces and destroy them.

Admiral Kurita decided to pass north of Palawan, go around the island of Mindoro and through the San Bernardino Strait, and approach Leyte from the north. Nishimura’s force would steam south of Palawan and enter Leyte Gulf from the south, through Surigao Strait. A force of three cruisers and four destroyers under Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima would come down from the north to reinforce Nishimura. If all went according to plan, these groups would converge on the American forces in Leyte Gulf at dawn on October 25.

This was to be the decisive battle—a phrase that often turns up in Japanese reports and dispatches—that would give the Americans a setback from which they would never recover. It would also allow Japanese troops in the Philippines to maintain contact with their bases in Malaysia and Indonesia, including Singapore. The plan was given the name SHO-1, phase one of SHO-GO, Operation Victory.

American naval intelligence was greatly relieved to receive Darter’s reports. Intelligence knew that Kurita’s fleet had sailed from its base at Lingga Roads, a little over 100 miles south of Singapore off the east coast of Sumatra, but had no idea of its whereabouts. American forces could not afford to have an enemy fleet of that size at large and undetected. One reason that Kurita decided to bring his task group north of Palawan and through San Bernardino Strait was to keep beyond the range of enemy reconnaissance aircraft for as long as possible. Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison said that Darter’s radio messages proved to be “the most significant reports of the Pacific war.”

Actually, the information Darter had sent was incorrect. In fact, Kurita’s task force consisted of five battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 13 destroyers. Two of the battleships were Yamato and Musashi, the largest warships in the world, larger even than the American Iowa-class battleships. But the exact details of the enemy’s strength were not all that important; the main thing was that Kurita’s force had been located. Lt. Cmdr. Benitez commented that aboard Dace the crewmen “were not too concerned with the overall picture.” Their primary thought was to get into firing position after Darter sent her contact reports.

Sinking Kurita’s Flagship

At 4:30 am on October 23, Darter was about 20,000 yards ahead of Kurita’s port column, which was led by the cruiser Atago, Admiral Kurita’s flagship. Dace would attack the starboard column, while Darter went after the ships in the port column. The crews went to battle stations at about 5:00, at least those who had not gravitated toward their stations already.

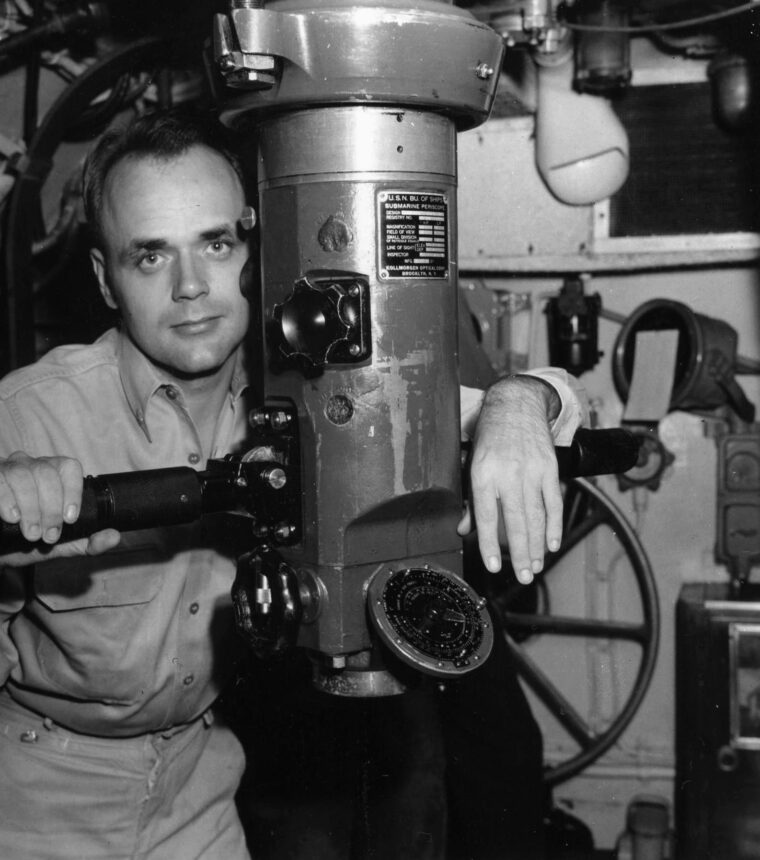

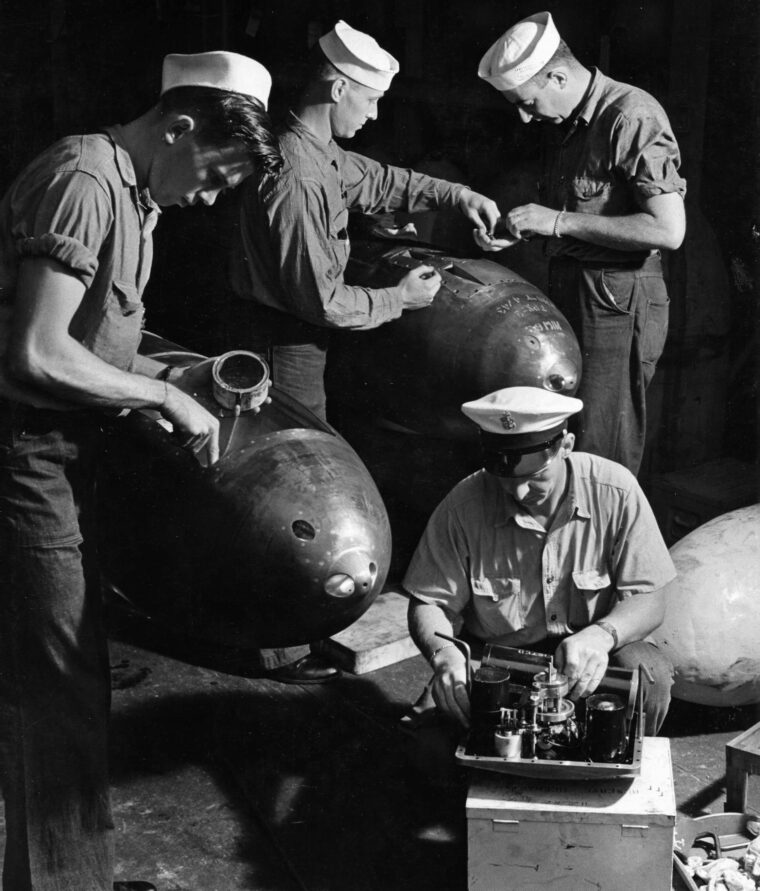

Darter submerged at 5:10, disappearing from Dace’s radar. Dace submerged a few minutes later. The operators of the target data computers (TDC) on both submarines began asking for the range of the target the captain had chosen. When the TDC man was given the range, he entered it into the computer and gave the torpedo settings to the captain.

Darter fired her torpedoes first, at 5:32. Fleet submarines of the Gato class, which included both Dace and Darter, had six bow torpedo tubes and four stern tubes. Commander McClintock fired all six bow torpedoes at the leading cruiser, at a range of only 980 yards. After a very short running time, four of the six hit the target. The explosions were heard by everybody on board both Dace and Darter. McClintock’s curiosity got the better of him; he looked through the periscope before going after the next target.

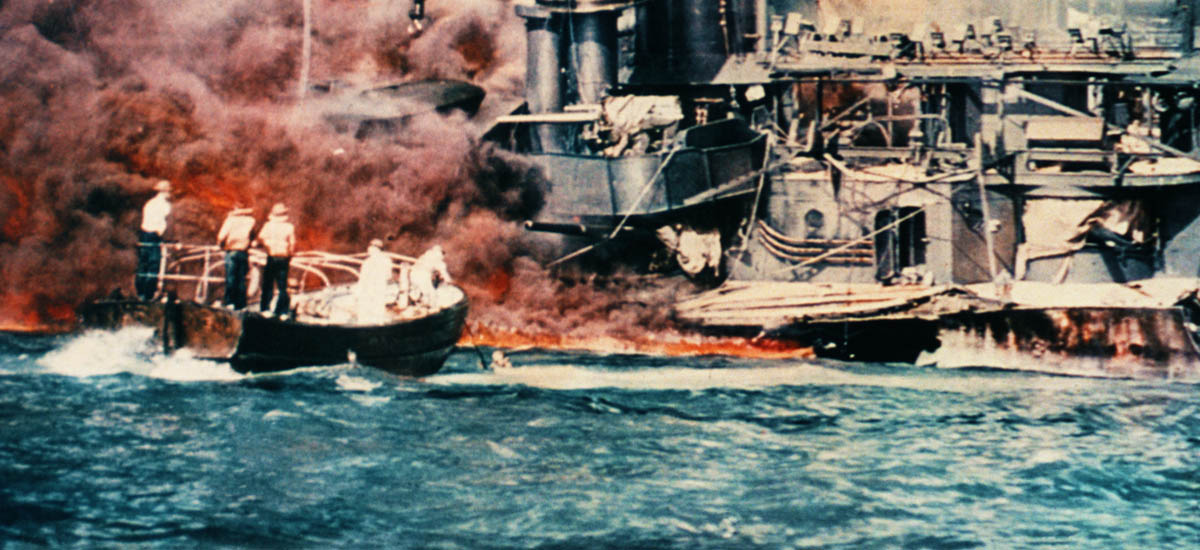

“Whipped periscope back to the first target to see the sight of a lifetime,” McClintock noted in his report. “Cruiser was in so close that all of her could not be seen at once with periscope in high power. She was a mass of billowing black smoke from No. 1 turret to the stern. Cruiser was already going down by the bow.”

The cruiser was Admiral Kurita’s flagship, Atago, which was going down quickly. By 5:40, only eight minutes after being hit by Darter’s torpedoes, the sounds of the ship breaking up could be heard inside Darter’s pressure hull. Thirteen minutes later, Atago sank bow first, taking 360 officers and men with her. Admiral Kurita and his staff survived but had to jump overboard and swim to their rescuers. Rear Adm. Matone Ugaki, aboard the battleship Yamato, assumed command of the task force until Kurita could transfer his flag—meaning until he had the chance to dry off and compose himself.

“It Looks Like the Fourth of July Out There!”

By this time, McClintock had already emptied his stern tubes at the next ship in the column, which was the heavy cruiser Takao. Two of the four hit at 5:34, blowing off the rudder and two propellers and flooding three boiler rooms. Darter’s crew heard the explosions and thought they had sunk Takao as well. But Japanese cruisers of that class had triple hulls and were said to be unsinkable. Takao certainly lived up to that description. She stayed afloat; escorted by destroyers, the badly damaged cruiser limped toward the naval base at Brunei at five knots. She would live, but she was out of the coming battle.

Through his periscope aboard Dace, Commander Claggett watched Atago sinking and Takao listing and badly damaged. “It looks like the fourth of July out there!” he shouted to everyone on the conning tower. “One is sinking and the other is burning. The Japs are firing all over the place. What a show!” Claggett then turned the periscope toward the enemy’s starboard column. “Stand by for a set-up,” he said. He allowed the first two ships to pass by. The third ship appeared to be a Kongo-class battleship; this would be the target. The ship Claggett had chosen as his target was, in fact, the heavy cruiser Maya.

The fire-control officers sounded ranges and bearings and angles on the bow. Benitez relayed everything to the captain. When the target was in position, Claggett ordered all six bow torpedoes fired, just as McClintock had done aboard Darter.

“The offensive phase was over,” Benitez said after all torpedoes had been fired. “Now it was time to start running.” Claggett ordered, “Take her deep.” As Dace began her descent, the boat was shaken by explosions “as if the ocean bottom was blowing up.” Four of her torpedoes had hit the cruiser, each carrying a warhead of more than 600 pounds. The explosions were followed by a noise that Benitez described as “Gruesome. It was akin to the noise made by cellophane when it is crumpled.” The crackling noise was so loud that it sounded like the submarine was breaking up; Claggett had all of Dace’s compartments checked. To everyone’s relief, all compartments reported no damage.

Dace had not been damaged, but Maya had blown up and sunk immediately. On board Yamato, Admiral Ugaki watched as the cruiser blew up “and after the smoke and spray disappeared,” he reported, “nothing of her remained to be seen.” The loud crackling noises that had alarmed Dace’s crew had been Maya’s bulkheads imploding as the ship headed for the bottom.

Evading Depth Charges

While the sounds of Maya’s death throes faded astern and Dace settled down to a running speed, depth charges began exploding close by. Dace’s crew were surprised that the Japanese destroyers had not gone after Darter instead; her sister submarine was running ahead of Darter and would have presented a more convenient target. The sound man gave a running narrative of what was going on above. “Four of them are making a run now, Captain,” was one observation. The Japanese destroyers “sounded like an electric razor at work on a two-day beard.” The crew could hear them coming, but only the sound man could tell how many were coming.

The depth charge attack continued while the two columns of enemy warships left Darter and Dace behind and continued up the Palawan Passage. “They were going off all around us and they were close,” Benitez recalled. The boat rocked; light bulbs shattered; locker doors flew open from the shock. Some of the destroyers made dry runs, dropping no depth charges. Their main intent seemed to be keeping Darter and Dace occupied while the rest of the task force got away.

After about an hour and a half, the destroyers joined the rest of Admiral Kurita’s fleet and headed off to the northeast. The two submarines stayed deep for a while, making certain that the destroyers had gone before coming up to periscope depth. Both saw Takao dead in the water and also noticed two destroyers standing by as well as two aircraft flying cover over the badly damaged cruiser. “We attempted to get in another attack during the day,” Benitez later wrote, but they could not get close because of the destroyers and the aircraft. The joint attempt by Darter and Dace to get into firing position lasted five hours.

Stalking the Takao

It had been a frustrating time, but the crews of both submarines were not all that concerned. They held the cruiser in view at all times and would wait until after dark to finish it off. During the rest of the day, both crews managed to get some much needed rest. After sunset, Darter and Dace both surfaced and steered side by side again. The two captains conferred on how to go about finishing off Takao.

They decided to make a surface attack, but expected that the cruiser would be towed by the two destroyers. To everyone’s surprise, Takao got underway under her own power. She began heading southwest at about six knots. This presented a new situation; torpedoing a moving target presented different conditions from shooting a sitting duck, even if the target was only moving at six knots. The two captains would split their attack—Darter would make her attack from the east while Dace made an end run around from the west. By midnight on October 24, the two submarines were still getting into position for their torpedo attack. Darter was making 17 knots, trying to attack before Takao could pick up more speed.

For the past 24 hours, both submarines had been navigating the Palawan Passage by dead reckoning only. Because they had spent so much time submerged during the daylight hours, navigators were not able to get a fix on the mountains on Palawan, which meant that they were not exactly certain of their position. Clouds obscured the stars after sunset, so they were not able to get a celestial fix, either.

To evade the screening destroyers, Commander McClintock planned to leave a margin of seven miles to Bombay Shoal, which is a coral reef on the western side of Palawan Passage. A quarter-knot error in estimating the current put Darter on a collision course with the reef. At 12:05 am, Darter’s crew found out exactly why that stretch of water was called the Dangerous Ground.

“Like a Ship in Drydock”

Darter ran hard aground on Bombay Shoal with a tremendous crash. The noise registered on the sound gear of one of the enemy destroyers, which immediately began heading toward it. Fortunately for the grounded submarine and its crew, the destroyer was not able to detect what had happened. It closed to within 12,000 yards and turned away. “When the Jap destroyer faded on our radar screen we breathed a little easier,” McClintock understated, “and went to work in hopes of floating her off at high tide.” To lighten the boat, the crew threw everything movable overboard—anchors, food, furniture. The stern torpedoes were also fired, jettisoning several tons of dead weight. In an attempt to raise the bow, the crew gathered on the submarine’s stern. Some of the men also tried to rock the boat free by running from port to starboard and back again. Nothing worked. Darter was stuck, high and dry.

Aboard Dace, Commander Claggett had no choice but to go to Darter’s assistance. Commander Benitez recalled, “It was hard to give up pursuing a ship that we knew would probably sink with one torpedo hit … It would have been doubly hard to abandon our comrades to certain death on the shoals of Palawan Passage.”

Dace moved slowly and cautiously closer to Darter; Claggett had no desire to run his own boat up on a reef in the dark as well. McClintock shared Claggett’s fears. He shouted over to Dace not to come too close, to stay out a bit, and to watch out for the reef. Dace closed to within 50 yards of Darter’s stern, close enough to send over a line. There was no doubt that Darter was in a hopeless situation. Benitez observed, “She was so high that even her screws were out of the water—she seemed like a ship in drydock.”

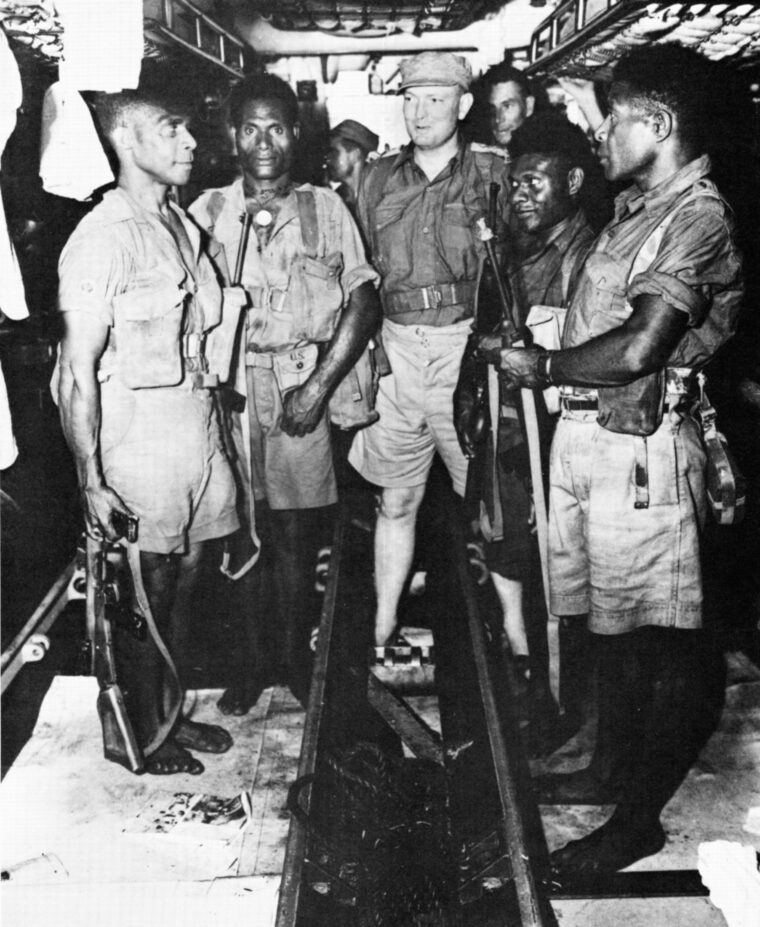

It became evident that Darter would never get off the reef. The crew began burning secret documents and destroying vital equipment, including the radar and radios, with sledgehammers. Both submarines inflated their rubber rafts; Darter’s crew began its slow transfer over to Dace. “In the darkness, gnome-like figures on the deck of Darter were seen to go down her side into rubber boats awaiting them below,” Benitez recalled. “Minutes later, they reappeared at the side of Dace, where willing hands hoisted them aboard.” Each raft held only six men. Two and a half hours were needed to transfer all of Darter’s crew. Benitez noted that McClintock was lifted aboard at 4:39 am. He was the last man to leave the boat.

Blowing up the Darter

McClintock lost no time in reporting that he had set Darter’s demolition charges—50-pound devices that had been installed aboard every submarine for just such a situation. Dace moved away at full speed, not wanting to be damaged by the coming explosion. But only one of the charges went off, with a comical pop. Darter was still very much intact and would be of use to the Japanese if captured. It made no difference why the explosives failed to detonate—Darter still had to be destroyed, or at least be made unusable to the enemy.

Dace had four torpedoes remaining; these would be used against Darter. Two torpedoes were fired at her beam. Both hit the reef. Next, Dace came directly astern and fired her last two torpedoes. These also exploded against the reef—the submarine was too high out of the water. By this time it was about 5:30, and the sun was beginning to come up. The two captains decided to use Dace’s deck gun.

Firing Dace’s gun meant that the gun crew would have to be on deck during the surface action, which would be risky if a Japanese destroyer or aircraft appeared, but it was a risk that both Claggett and McClintock thought was worth taking. The gun crew opened fire and began scoring telling hits on Darter, according to Benitez. To be exact, Dace’s gunners hit Darter 21 times. The superstructure and the hull were holed repeatedly. Dace’s supply of ammunition was being quickly used up as Darter was systematically destroyed. The 25 or 26 men on deck were concentrating on the gunnery display when the radar operator shouted, “Plane contact—six miles.” Claggett immediately ordered, “Clear the deck!”

The activity aboard Dace instantly went from the orderly firing of the boat’s deck gun to a scene out of a Keystone Cops film. The only open hatch—which was about two feet wide—was on the conning tower. Everybody on deck made a frenzied dash for the hatch as Dace began to submerge. Some managed to climb down the hatchway, but others fell down sideways, dove down head first, or were pushed down in a heap. The Officer of the Deck closed the hatch just a few seconds before the boat went under. There were more than a few bruised shins and mashed fingers, but everyone got below safely. In the course of both the rescue operation and the gun action, not a man from either Darter’s or Dace’s crew was lost.

The approaching plane spotted the two submarines—one dead in the water, the other submerging and making rapid headway. The pilot elected to attack the easier target. He did not realize that Darter was aground and had been abandoned. All he saw was a sitting target and went after an easy kill. He dropped his bomb on Darter and flew off, much to the relief of everybody aboard Dace.

The Japanese Fleet Intercepted

Having done everything possible to make Darter useless to the enemy, Dace was set on course for Fremantle, Australia. On board were 81 officers and men from Darter along with Dace’s own compliment of 74. The boat was overcrowded. Life aboard a submarine was cramped and confined under normal conditions; now it was twice as crowded. The trip to Fremantle took 11 days but probably seemed a lot longer for the 155 men on board. Men slept on the empty torpedo skids and any place else that was not already occupied. During the last few days of the journey, the only food remaining was peanut butter and cream of mushroom soup. But the trip itself was uneventful, and Dace arrived at Fremantle on November 6. Everyone on board was relieved to get ashore, but also realized they were lucky to be alive.

Around noon on October 24, Admiral Kurita received a dispatch from Combined Fleet in Tokyo. It began: “It is very possible that the enemy is aware of the fact that we have concentrated our forces …” Kurita did not need any message from some staff officer in Tokyo to tell him that. He had lost three cruisers, including his own flagship, and could guess that the same American submarines that torpedoed his flagship out from under him had also radioed his position.

Tokyo was right. Admiral Halsey certainly was aware of Kurita’s presence, thanks to Darter’s warnings. Kurita’s force steamed through the Palawan Passage into the Sibuyan Sea. Alerted by Darter’s contact reports, Halsey ordered his aircraft carriers to launch air strikes against Kurita in the opening phase of the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. The carrier-based planes sank the giant battleship Musashi with 19 torpedoes and 17 bomb hits. Also, the heavy cruiser Myoko was damaged and steamed for Brunei for repairs where she would join the torpedoed Takao. As the battle went against him, Kurita turned back toward San Bernardino Strait. By this time, he was seven hours behind schedule, and the Japanese timetable was in serious trouble.

Kurita’s diminished but still powerful fleet encountered six escort carriers of Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague on October 25 off Cape Engano. The six carriers, escorted by three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, were ridiculously outgunned by Kurita’s battleships and cruisers. Sprague made smoke, launched his aircraft, and tried to get his escort carriers away from Kurita. The escorts attacked with torpedoes, damaging one cruiser and sinking another. Admiral Sprague lost one carrier, two destroyers, and two destroyer escorts to the overwhelming gunfire of the enemy. However, instead of continuing his advance, wiping out Sprague’s undergunned fleet, and attacking the support vessels lying off the Leyte invasion beaches, Kurita chose to withdraw. Still shaken by the attack by Darter and Dace, he believed that Sprague’s escort carriers and destroyers were part of a much larger task force. Kurita decided to play it safe and turned away.

A Catastrophic Defeat for Japan

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was decisive, but it had not gone the way Combined Fleet commanders had hoped. The fighting in and around Leyte Gulf, which lasted three days, was a catastrophic defeat for Japan. The losses suffered by the Japanese Navy left it unable to support Japanese land forces in the Philippines, or even to defend Japan itself. Darter and Dace played a vital role in that defeat.

One week after Darter ran aground, the submarine USS Nautilus bombarded Darter with 55 rounds from her deck gun. According to the captain’s report, “It is doubtful that any equipment on Darter … would be of any value to Japan except as scrap.” That evaluation proved to be correct. Darter remained high and dry on Bombay Shoal, where the wind and weather took its toll over the years. To this day, sailors that travel along the Palawan Passage can see Darter’s hulk, ravaged by both gunfire and the elements.

David Alan Johnson is the author of the book The City Ablaze, which is an hour-by-hour eyewitness account of the December 29, 1940, fire blitz on London. His most recent book, BETRAYAL: The True Story of J. Edgar Hoover and the Nazi Saboteurs Captured During World War II, was published in November 2007. He resides in Union, New Jersey.

Dave McClintcock was a resident of Upper Michigan and a soft spoken gentleman who was a real hero to members of our community. A life sized replica of the Dasher’s conning tower sits next to the Coast Guard Station and the Maritime Museum in Marquette, MI. In recognition of these heroes of Leyte Gulf. They changed the battle and left no one behind.

My father was a crew member of the USS DACE during this battle. He told me the story of what the crew did. He was on his way to the dedication when 911 hit and was not able to go there. I am planning on a visit there this summer.

Never understood why Admiral Kurita turned and ran. I always thought they were on a final or suicide mission to take on and destroy the American landing forces and the supporting American battle fleet. This was supposed to be the final assault against the Americans and the Japanese knew it. Why they turned and ran, instead of chasing down the enemy and fighting to the last ship is a contradiction.