By Peter Kross

The night of April 14, 1865, was one of celebration in Washington, D.C. Just a few days earlier, on April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the small crossroads town of Appomattox, Virginia. The event effectively ended the American Civil War, which had torn the country asunder for nearly five years.

The bloodiest war in American history had finally come to an end, and the Union had been preserved.

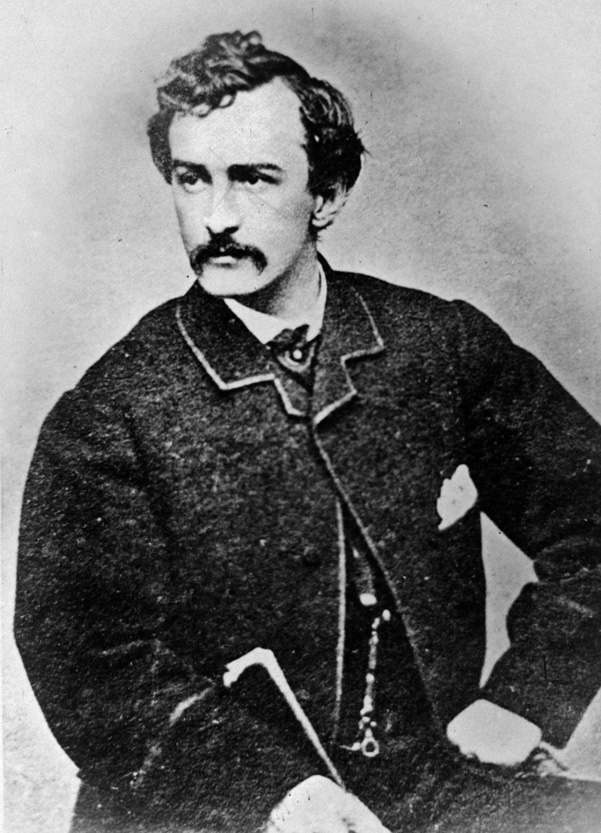

On that fateful April 14, John Wilkes Booth, the son of one of the most famous theatrical families in the nation and an accomplished actor in his own right, walked into a tavern next to Ford’s Theater in Washington. Booth made small talk with the bar owner, discussing the end of the war. Booth, an ardent Southern sympathizer, was a small-time agent for the Confederacy, taking medicine and other goods from the North to the South without anyone being the wiser.

After leaving the tavern, Booth made his way to Ford’s Theater where a play called Our American Cousin was being performed. Booth knew the layout of the theater well, having performed many times at the establishment owned by John Ford. Having spied the layout and seating of the theater beforehand, Booth quietly slipped into the box where President Abraham Lincoln, first lady Mary Todd Lincoln, and their guests were watching the play. Booth silently opened the unguarded door and in a moment’s horror shot Lincoln in the back of the head, mortally wounding him.

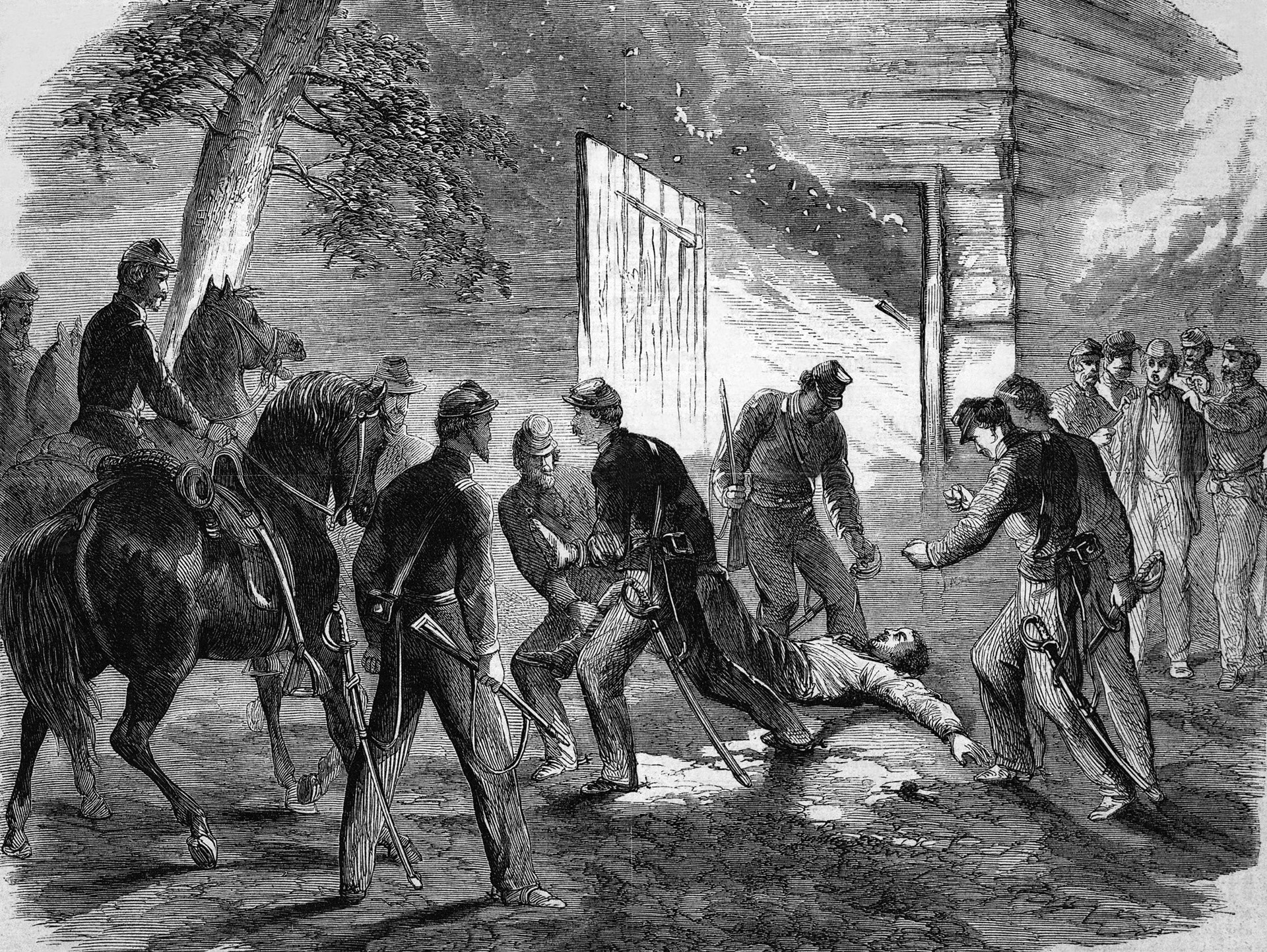

In the chaos that followed, Booth and accomplice David Herold made their way into Maryland, winding up at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, a local physician. Mudd, who had previously met Booth on two occasions, treated his leg, famously broken when Booth jumped from Lincoln’s box to the stage below. The next day, both men left Mudd’s home and began their 12-day flight from the massive manhunt that was in progress. Booth was later shot and killed buy federal troops at the farm of Richard Garrett.

It is not widely known that Booth was associated with many people who belonged, in one way or another, to the Confederate Secret Service and the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, headed by President Jefferson Davis. New information unearthed in recent years paints an elaborate picture of just how far the Confederate government went to ensure Booth’s escape from Washington after the assassination of Lincoln.

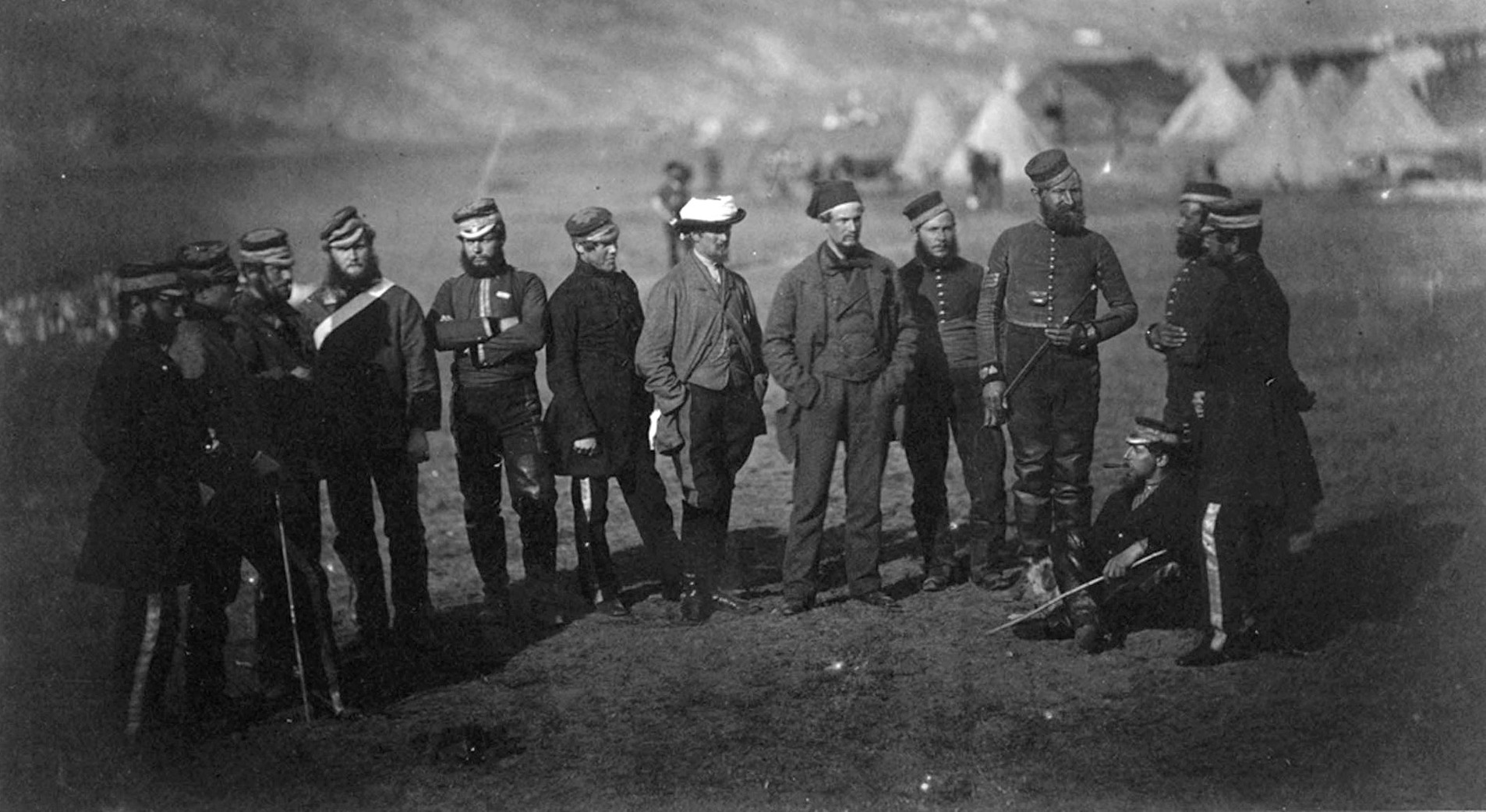

As the trial of the Booth conspirators began in Washington, a military tribunal set out to prove that the assassination of the president was funded and carried out by the Confederate government in Richmond. The crime was one so monstrous that it could not have been carried out solely by Booth and his band of lowly miscreants. The military tribunal wanted desperately to connect the deed to anyone behind Booth, and the government in Richmond was the perfect foil.

One of the first prosecution witnesses was Charles Dunham, who went by the aliases Sanford Conover and James Watson. Dunham said that he had concrete information that the assassination had been ordered by Davis and the plot had been hatched in Canada. Dunham coerced two other witnesses, Richard Montgomery and James Merritt, to back up his absurd claims. All of them said that they saw Booth and fellow conspirator John Surratt in Canada talking with Jacob Thompson, the head of the Confederate Secret Service, who was operating openly north of the border.

Dunham’s testimony was headline news, but soon it began to fall apart. Seeing the writing on the wall, Dunham recanted his story, but the damage had been done.

Not all of what Conover said was false regarding Booth and his association with the Richmond government. Booth had contact with various individuals who were linked with the Confederate Secret Service, although that fact was not brought out in the trial of the conspirators.

Booth was an ardent Southern sympathizer, but did not join the Confederate Army once the war started. He decided to use his fame as one of the nation’s premier actors to further the Confederate cause in his own way. During the war, Booth was a low-level courier for the Confederates and smuggled medicine to the South, doing a little spying along the way. Booth’s sister, Asia Booth Clarke, in a book that she wrote titled The Unlocked Book, said, “I now knew that my hero was a spy, a blockade-runner, a rebel! I set these terrible words before my eyes, and knew that each one meant death.”

During the war, Booth traveled to such places as Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Montreal, Canada, meeting with Confederate agents. Booth confided to his actor friend Samuel Chester in New York that he was planning to kidnap or kill Lincoln and asked Chester if he would like to join in, but he refused. Booth further told Chester that he had at least 50 persons allied with him.

Another link connecting Booth to the Confederate government is his trip to Montreal on October 18, 1864. In the spring of 1864, the Confederate government decided to send agents to Canada, where they would plot against the Union. Davis chose Thompson of Mississippi to head the operation and sent Clement Clay as Thompson’s assistant. One million dollars in gold was authorized to fund the operation. It was drawn from a special Secret Service account authorized by Davis and Confederate Secretary of State Judah Benjamin.

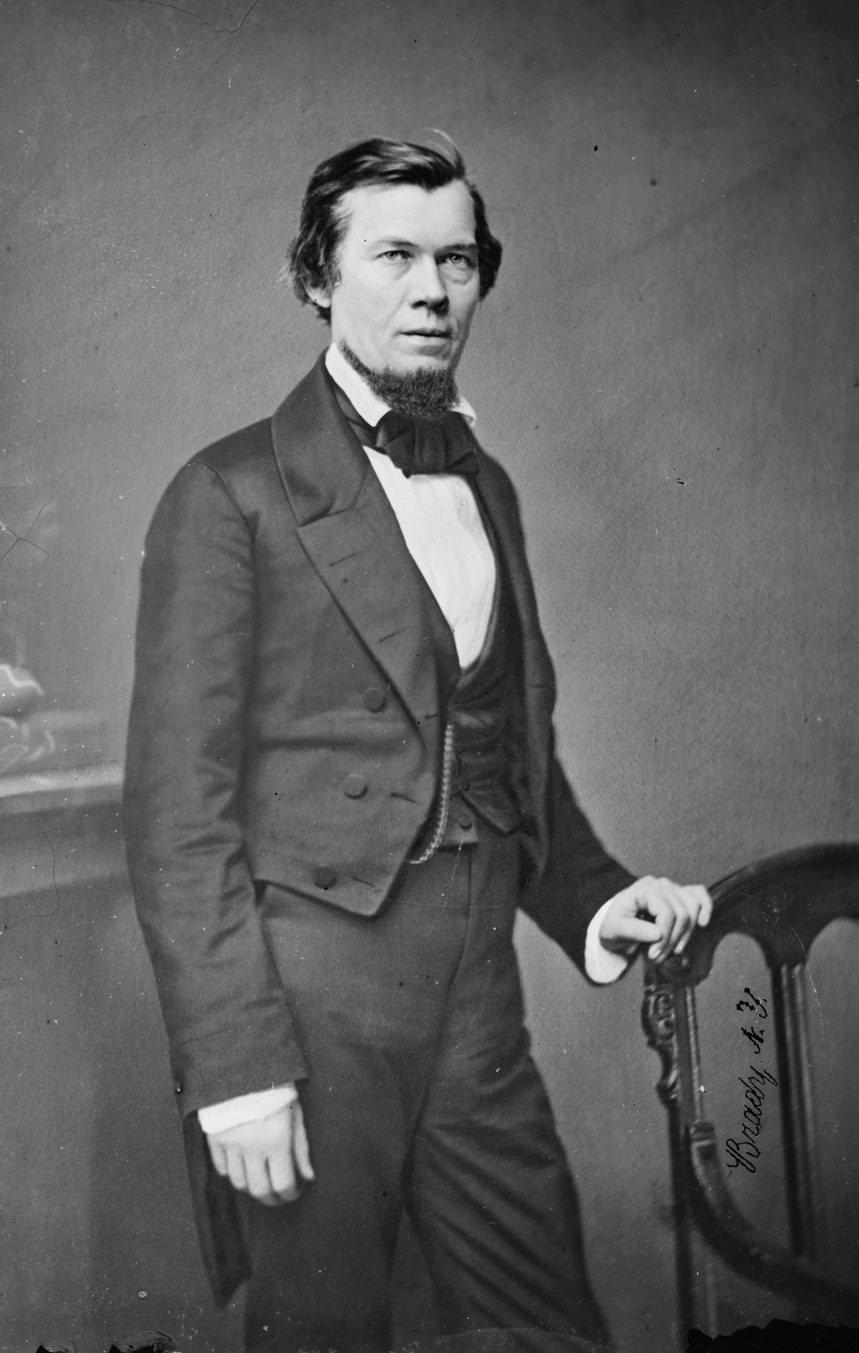

Benjamin was one of the few Jews to rise to prominence in the United States at that time. He was born on August 6, 1811, in St. Croix, which at the time was part of the Danish West Indies occupied by the British crown. In 1813, his parents immigrated to the United States. The family resided at first in Wilmington, North Carolina, but eventually moved to Charleston, South Carolina. After briefly attending Yale University, Benjamin moved to New Orleans in 1832 and became a lawyer.

Benjamin served in the Louisiana state legislature, and in 1852 he became the second Jew to be elected to the U.S. Senate. He was an ardent Southern sympathizer, and during the war he served as the Confederate States’ attorney general, secretary of war, and secretary of state. Benjamin was responsible for the distribution of money from the Secret Service fund, and he handed some over to one of Booth’s accomplices in the plot to kidnap or kill Lincoln. John Surratt’s mother, Mary, owned a home in Washington, where the Booth conspirators met to plan the president’s abduction or assassination.

The conspirators set up shop in Toronto, as well as other cities in Canada. The man in charge of the Montreal office was Patrick Martin, who gave Booth letters of introduction to Mudd in Bryantown, Maryland. Another person who aided the Confederates in Canada was George Sanders, an advocate of political assassination and a Lincoln hater.

Among the plots hatched in Montreal were plans to raid Union towns in New York and New England, free prisoners held in Union jails across the border, poison the water supply in New York City, and spread yellow fever in certain Union states to cause panic among the population.

Booth arrived in Canada on October 18, 1864, and registered at the St. Lawrence Hall Hotel, a hotbed of Confederate operations in Canada. For the next 10 days, Booth had various meetings with Martin and Sanders, and it is possible that the Confederate plot to either abduct or kill the president was discussed.

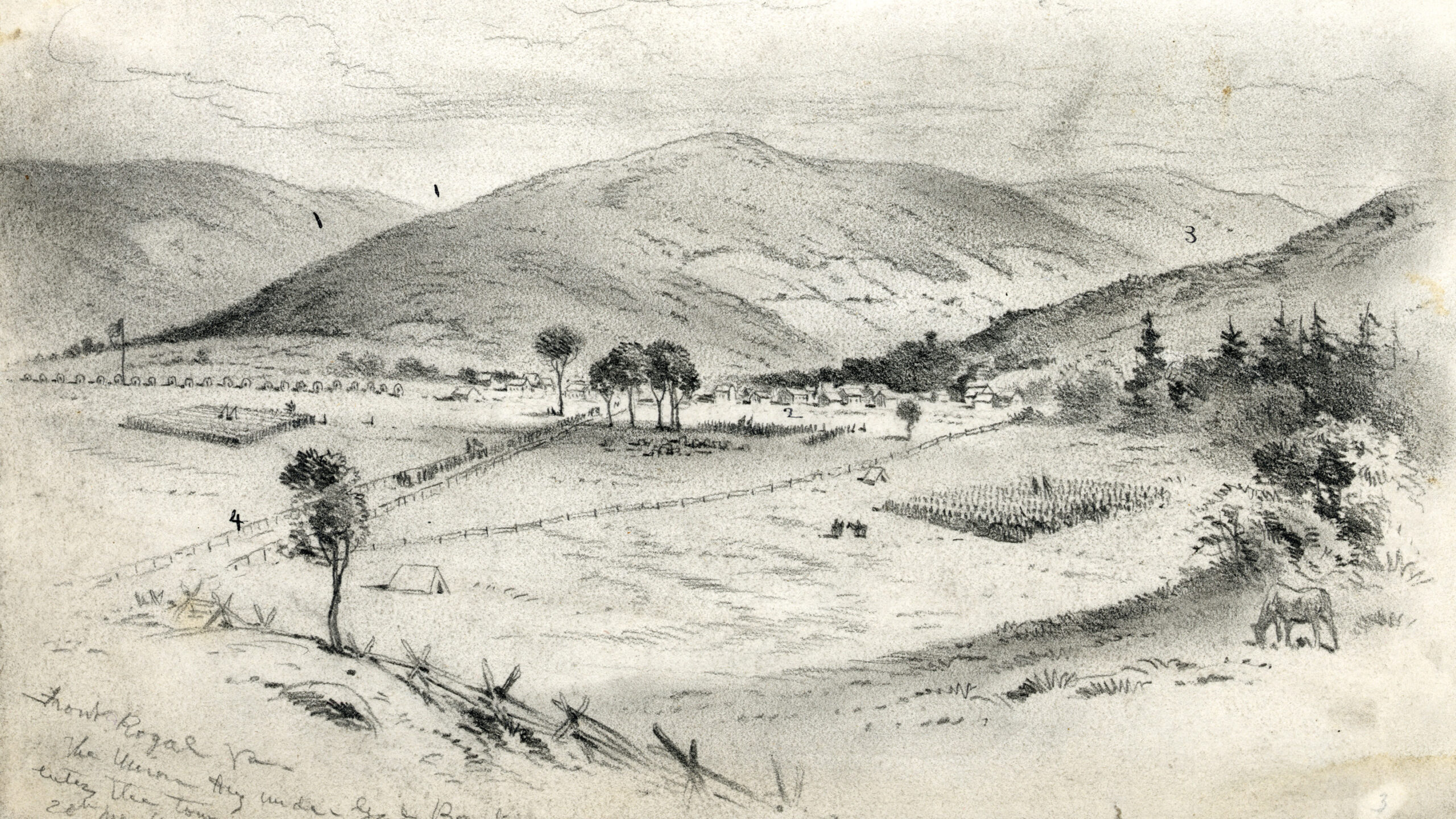

Another link to the Confederate government in Canada was an Episcopal minister by the name of Reverend Doctor Kensey Johns Stewart, who traveled from Canada to the Southern states around the same time that Booth was in Canada. In October 1864, Stewart arrived in southern Maryland and wound up in the place where Lincoln was to be taken if the abduction plot had succeeded.

Stewart eventually arrived in northern Virginia at a secret Confederate Signal Service unit that was headed by Lieutenant Charles Cawood. In September 1864, both Cawood and Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby were given orders by Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon to help Captain Thomas Nelson Conrad, who was given the job of abducting Lincoln and taking him to Richmond. Stewart went to Richmond, where he conferred with Davis and then returned to Canada with $20,000 supplied by the Confederate Secret Service. It is not known if Stewart met with Booth while they were both in Canada, but Stewart was involved in some way with the plot to kidnap Lincoln.

While in Montreal, Booth was able to use money depositied for him in the Ontario Bank in the amount of $455 Canadian. This money was most likely supplied to him by Confederate commissioners then living in the city. Immediately after leaving Canada, Booth came to Washington and made deposits in a bank owned by Jay Cooke.

A check $100 was written on November 16, 1864, on the account of Jay Cooke and Company, at a bank in Washington. It was payable to a Matthew Canning, a long-time friend and theatrical agent of Booth. A total of seven checks were drawn on the account, including the $100 from Canning, a $150 check cashed by Booth on January 7, 1865, and another one for $25 also cashed by Booth on March 16, 1865. Booth made these deposits in Cooke’s bank just after he made his covert trip to Montreal.

When Booth was killed at Garrett’s Farm, soldiers found a Canadian bill of exchange on his body. This paper trail is just one of many things that tie Booth to the covert activities of the Confederate Secret Service and its relationship to the assassination of the president. When federal detectives searched the room of George Atzerodt (he was supposed to have killed Vice President Andrew Johnson but lost his nerve), after the assassination, they found Booth’s bank book with the $455 amount duly noted.

One year after his Canadian sojourn, Booth and his accomplices devised their plan to kidnap Lincoln when he was to attend a performance at the Campbell Military Hospital about two miles from the U.S. Capitol. The date set for the abduction was March 17, 1865, and the performance was moved to the Soldiers Home. The purpose of the show was to benefit wounded Union soldiers.

Booth and his men waited on the road from the hospital. Their plan was to capture Lincoln, spirit him south, and then use Lincoln to ransom the thousands of Confederate troops languishing in Federal prisons. Much to their disappointment, Lincoln’s plans changed, and the opportunity was gone.

Booth’s plan to capture Lincoln mirrors exactly one concocted by the highest officials in the Richmond government in 1864. In that plan, Conrad was to carry out the abduction. Conrad, who had previously served in the Confederate cavalry, had by that time transferred to the Confederate Secret Service and was directed by Benjamin.

Years later, Conrad wrote that he was given letters from Davis to Seddon and Benjamin transferring him to the Confederate Secret Service and was provided funds for the mission. Others involved in the planning were Lieutenant Charles Cawood of the Signal Service and Mosby, who were to provide aid to the fleeing Conrad. Conrad went to Washington and followed Lincoln’s movement for a few days.

After watching Lincoln, Conrad told his superiors that the president was too heavily guarded to make any attempt to capture him, and the plot was terminated. Conrad later wrote, “[Had] Lincoln fallen into the meshes of the silken net we had spread for him, he would never have been the victim of the assassin’s heartless, bloody crime.” The Conrad plot had been approved by the top men of the Confederate government: Davis, Benjamin, and Seddon.

The question that historians have asked is, Did the Confederate government in Richmond actively play a role in the plots to kidnap or assassinate Lincoln? The circumstantial evidence gathered in the past 150 years dictates that it did.

Once Booth fled Washington after the assassination, he was aided and abetted by a number of people who had direct ties or indirect contact with him before and after the assassination. Following is a short list of the people who helped Booth and their roles in the Lincoln assassination plot.

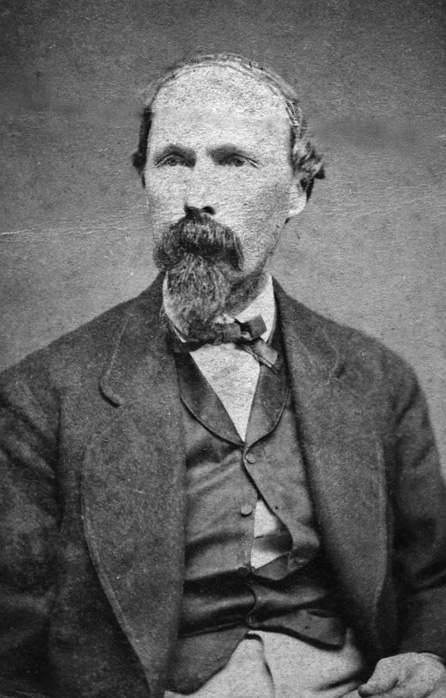

Dr. Samuel Mudd. He set Booth’s broken leg at his farm, had at least three previous meetings with Booth in Washington and at his home, and knew a number of people in the plot to kill the president, including Surratt, Cox, and Harbin.

John Surratt. He was the son of Mary Surratt, who owned the boarding house in Washington where the conspitators met, as well as a tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, which was a way station for Confederate agents and smugglers. He was well acquainted with Booth and was part of the kidnap plot against Lincoln. He was in contact with Roderick Watson, a member of the Confederate spy network in Charles County, Maryland.

In New York, Watson used a mail drop at 178 1/2 Water Street. Booth frequently was in New York plotting strategy, and on March 19, 1865, Watson sent a letter to Surratt asking him to come to New York on urgent business. Surratt was a dispatch rider between Richmond and Confederate agents in Canada. Mary Surratt also had frequent contact with Booth and was with him on the morning of the assassination, taking arms and ammunition to her tavern in Surrattsville.

Thomas Harney. He was a member of the Confederate Torpedo Bureau in Richmond and was an expert in the use of mines and explosives. On April 1, 1865, Harney was sent to join Mosby’s cavalry battalion in Virginia. On April 8, Harney’s unit was captured by Union troops. When Richmond fell on April 3, 1865, Union Colonel Edward Ripley was in the city. He was visited by a Confederate soldier named William Snyder. Snyder said that there was a Confederate plot to blow up the White House during a meeting of the president’s cabinet. Booth’s co-conspirator George Atzerodt stated, “Booth said that he met a party in New York who would get the president certain. They were going to mine the end of the White House next to the War Department.”

Thomas Harbin. Harbin was a Confederate agent who lived in Charles County, Maryland. He was once the postmaster at Bryantown, Maryland, the home of Mudd. When Booth paid a visit to Bryantown to see Mudd, the doctor introduced Harbin to Booth. It was during this meeting, which took place on December 18, 1864, that Booth recruited Harbin into his scheme to kidnap Lincoln. Harbin’s base of operations was on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, and he took his orders directly from Richmond. Harbin in turn enlisted Atzerodt into the kidnap plans. During the 12 days on the run, Harbin procured horses for Booth and Herold.

Thomas Jones. Jones was one of the most important Confederate agents in the region of Charles County and was also with the Confederate Signal Service. He played a pivotal role in the escape of Booth and Herold after the assassination. He was helped by Cox, at whose home Herold and Booth were staying.

Jones brought the pair newspapers, food, and blankets and did everything in his power to see to their safety. Jones moved Booth and Herold to the banks of the Potomac River, where a boat was waiting for them. Jones gave them a compass and candle for navigation assistance. The men got lost and wound up back on the same side of the river where they originally started. The Union authorities never realized how important a role Jones played in the escape of Booth and Herold.

Samuel Cox. Cox was a well-known Southern landowner and sympathizer, as well as a low-level Confederate agent. Following their stay at Mudd’s home, Booth and Herold arrived at Cox’s Rich Hill home. Cox gave them shelter and food until he could make further travel arrangements for them. Cox’s son went to Jones’ home, and a hurried meeting was held between Jones and Cox. The elder Cox agreed to help the two fugitives, and soon Booth and Herold arrived at his home. Cox had his overseer, Franklin Roby, escort the fugitives to the safety of a pine thicket, where they were hidden for the next few days. Cox then passed Booth and Herold to Jones for their trip south.

Cox was arrested but soon released. Again, the Union authorities had no idea just how much Cox had helped Booth and Herold. But he was just one more piece in the puzzle connecting members of the Confederate Secret Service to Booth’s escape. Like many in the drama, Cox was never charged for his role in the assassination plot.

Although there is no smoking gun that links the assassination to the top leaders of the Confederate government, the paper trail linking Booth to the numerous Confederate agents who aided him and were ready to help him escape from Washington after the assassination is undeniable.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments