By Michael D. Hull

A host of famous fighters and bombers in the Allied arsenal spearheaded the aerial offensives that helped secure victory against the Axis powers in World War II.

They included Great Britain’s Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Hurricane, Vickers Wellington, De Havilland Mosquito, and Avro Lancaster of Dambusters fame; and America’s North American B-25 Mitchell, Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk, Douglas A-20 Havoc, North American P-51 Mustang, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, immortalized by the best-selling novel and classic film Twelve O’Clock High.

Overshadowed by all was an aerial workhorse that served almost everywhere and did almost everything. Produced in greater numbers than any other American military aircraft, the four-engine, high-wing Consolidated B-24 Liberator was the only bomber to be used in all theaters of operation.

Big, ungainly, and disparaged as an underpowered, hard-to-fly “widow-maker,” the “Lumbering Lib” was not fully developed when World War II broke out and was essentially obsolete by the time it ended. But it proved rugged, had great endurance, and outdid the graceful, legendary B-17 in its speed, range, and operational ceiling. It carried more bombs than the Fortress, yet some Army Air Forces wags joked that it was “the packing box the B-17 came in.”

From early in the war until its end, and from England to the Atlantic and the Mediterranean to the Far East, Liberators were assigned to the longest, toughest missions. The durable B-24 was the most versatile American bomber. Before the advent of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, the Liberator was one of the few land-based heavy bombers used in the Pacific Theater because it could handle the long flights where no emergency landing fields were available.

Like that of the B-17 and many other U.S. wartime aircraft, the Liberator’s origin dated back to the mid-1930s and experiments with such “big bombers” as the Boeing XB-15 and Douglas XB-19. The necessity of a heavy bomber with superior performance grew critical in view of the tense political situation in Europe and Japanese militancy in the Far East. In January 1939, Maj. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Corps, foresaw the need for a bomber that could exceed 300 miles per hour and have a range of 3,000 miles and a ceiling of 35,000 feet.

Consolidated Aircraft Corporation founder Reuben H. Fleet and design engineer I.M. “Mac” Laddon were approached that month and asked to create a production outlet for the B-17. But Consolidated made a counteroffer to build a better plane. The company wasted no time and, after a period of frantic work, created a mock-up of a radically new type of bomber. Powered by four Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp radial engines, and equipped with a tricycle undercarriage to permit faster takeoffs and landings, Model 32 was designed around a high, low-drag wing patented by David R. Davis. This would increase the plane’s speed, range, and load capability.

Fleet, a U.S. Air Service pilot in World War I who had organized the first airmail flight from Washington, D.C., to New York, was proud of his plane but troubled about its aesthetics. The big, slab-sided bomber had an ugly snub nose, so he decided to add three feet to the fuselage and make it look prettier.

The Army selected Model 32 on February 21, 1939, and a month later ordered a single XB-24 prototype. Even before it made its maiden flight on December 29, 1939, Consolidated began to receive orders for its new bomber. Early test flights proved successful. That March, meanwhile, the Army ordered seven service-test YB-24s, six of which were eventually sold to Britain as transatlantic ferry transports. A French purchasing commission sought 139 of the planes. The British and French wanted the new plane. When France capitulated in June 1940, her order for the bombers was transferred to Britain.

Production continued at five eventual aircraft plants run by four companies—Consolidated at San Diego, California, and Fort Worth, Texas; Douglas at Tulsa, Oklahoma; Ford at Willow Run, Michigan; and North American at Dallas, Texas—and Liberators went into service with the newly formed U.S. Army Air Forces and the British Royal Air Force.

The American B-24s were initially used as transports and ferries, while the first batch to cross the Atlantic became unarmed transports for British Overseas Airways Corporation and crew ferries for the RAF Ferry Command. The second batch of planes joined RAF Coastal Command at Prestwick, Scotland, where they were modified and fitted with radar, increased armament, and Leigh lights for illuminating surfaced submarines at night.

The first B-24s to see action in World War II were deployed against German U-boats preying on Allied convoys in the Atlantic. Liberators helped to close the mid-Atlantic “gap,” where bitter battles were fought, and where U-boats had been beyond the reach of land-based planes and even the formidable Short Sunderland “Flying Porcupine” flying boats of Coastal Command. The long-range B-24 quickly established itself as highly effective in this particular combat role. Lockheed Hudson bombers could operate almost 500 miles from base, Wellingtons and Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys could spend two hours on station at that distance, the Sunderland could spend two hours at 600 miles, and the Catalina PBY the same amount of time at more than 800 miles. But the Liberator, with a maximum fuel load of 2,500 gallons, could spend three hours patrolling more than 1,100 miles from base.

B-24s proved invaluable in the long Allied struggle to turn the tide against U-boat wolf packs in the unforgiving Atlantic. Later, in March 1945, RAF Liberators sank seven U-boats in six days.

As production increased, more B-24 variants rolled off the American assembly lines and went into service with the USAAF and Allied air forces. The RAF took delivery of about 1,900 of the bombers, several hundred went to the U.S. Navy, and others served with the Royal Canadian, Australian, and South African Air Forces.

Manned by a crew of eight to 10 and mounting 10 .50-caliber machine guns, the Liberator was 67 feet long, had a wingspan of 110 feet, a cruising speed of 290 miles an hour, and carried a maximum bomb load of 12,800 pounds. Though eventually easy to mass produce, the B-24 was an advanced and complex aircraft for its time. It consisted of 1,225,000 parts held together by 313,237 rivets and cost $215,000 to build. The price tag for a B-17 was $187,000.

The bulky Liberator had a few faults. It required considerable strength to handle the controls. Pilots said that it was difficult to fly, particularly in formation and at altitudes above 20,000 feet, and that it demanded maximum skill. As one recalled, “In the air it was like a fat lady doing a ballet.” The plane’s distinctive twin tails made it slightly unstable, and its fuel system was flawed. The interior was roomy yet seemed cramped, and at high altitudes it was always numbingly cold. But the virtues outweighed the faults. As another pilot said later, “This was the workhorse of all the bombers.” Like the Fortress, it could take great punishment, hand it out, and get its crew home.

The production of B-24s, like that of Sherman tanks and Liberty ships, was one of the marvels of America’s wartime industry. The plane underwent almost continuous modification, with increases in bomb load and defensive firepower. On the half-mile-long assembly line at Ford Motor Company’s sprawling plant in the village of Willow Run 30 miles west of Detroit, a B-24 was assembled every 51 minutes when production reached its peak. A total of 19,203 Liberator variants were eventually built.

Shortly before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, two specially equipped B-24s flew to the Philippines for reconnaissance flights over enemy bases in the Caroline and Marshall Islands. One of these planes was destroyed on the ground at Hickam Field, Hawaii, on that fateful Sunday morning. Following the attack that thrust America into World War II, the 75 Liberator IIs awaiting delivery to the British were requisitioned by the USAAF.

While some of the new American bombers were rendering sterling service on antisubmarine sorties with RAF Coastal Command, others were readied to join B-17s in the gradual U.S. Eighth Air Force buildup in England. The 93rd Bomb Group was the first to arrive in England with B-24Ds in September 1942. Nicknamed “The Traveling Circus,” the group had made the first formation crossing of the North Atlantic by Liberators. Other B-24s were deployed to the Middle East, where they served with the USAAF and the RAF.

In May 1942, a force of 13 B-24Ds led by Colonel Harry H. Halvorson was assigned to fly to China and join the Tenth Air Force for raids against Tokyo. Its staging base was the RAF airfield at Fayid on the Great Bitter Lake in northeastern Egypt. Halvorson’s detachment did not make it to the Far East, but instead gained the first public attention for Liberators. On June 12, they took off on a mission to attack the oil refineries at Ploesti, 35 miles north of Bucharest, Romania. It was the first USAAF heavy bomber mission and the first of several attacks by B-24s based in North Africa on Nazi Germany’s vital source of petroleum.

The bombers flew over the refineries at low level in heavy cloud cover and caused minimal damage. There were no American losses during the 2,400-mile round-trip operation, but only seven bombers landed as planned in Iraq, two made it to Syria, one crash-landed, and four were interned in Turkey. Another such mission the following year would also prove disastrous.

B-24s flew their first combat mission from England on October 9, 1942. Colonel Edward J. Timberlake, Jr.’s 93rd Bomb Group took off from Alconbury and took part in a five-group raid on the French city of Lille. Sergeant Arthur Crandall, one of Timberlake’s gunners, shot down a Focke-Wulf 190 fighter that day to chalk up the first aerial victory for an Eighth Air Force Liberator.

The next B-24 group to reach England was the 44th Bomb Group, the “Flying Eight Balls,” which arrived at Shipdham on November 7. Although its first operation consisted merely of seven bombers creating a diversion for an attack by Fortresses, the 44th Bomb Group was destined to take part in 343 missions up to April 1945. It flew more missions and dropped more bombs (18,980 tons) than any other B-24 group except the 93rd. Over the course of the war, the group lost 192 planes and claimed 330 Luftwaffe fighters destroyed.

The 93rd Bomb Group was uprooted from England and deployed to North Africa on December 13, 1942. As part of the Twelfth Air Force and later the Ninth Air Force, its Liberators flew strikes against Axis supply ports. The air and ground crews had to cope with primitive facilities, furious winds, rain, and mud. Sometimes it was impossible to taxi a B-24D because the mud was such an obstacle. The group mounted 22 missions in 81 days before returning to England.

The numbers of Liberators grew so great that for most of the war, they constituted one-third of Eighth Bomber Command’s strength and outnumbered Fortresses in bomber groups in the Mediterranean and Pacific Theaters. By the end of 1943, there were more than 550 B-24s in Europe. The RAF, meanwhile, began using Liberators in the Middle East in June 1942 and then in the Indian Ocean area.

B-24s were not well liked in the European Theater because of the difficulty in mixing B-24 and B-17 formations, the respective flight per formance capabilities of which were not compatible. There was a defensive need for tight formations in missions over Germany. B-17 crewmen joked that their best escorts were Liberators because they attracted enemy fighters. The B-24 performed better over North Africa and Italy, and even superlatively in the Pacific Theater.

Electronically modified and flying singly at low level, B-24 night raiders had a remarkable success rate in the Pacific. There, Liberators almost completely replaced the shorter-range B-17s and carried most of the burden of USAAF bombing operations until the Superfortresses arrived late in 1944.

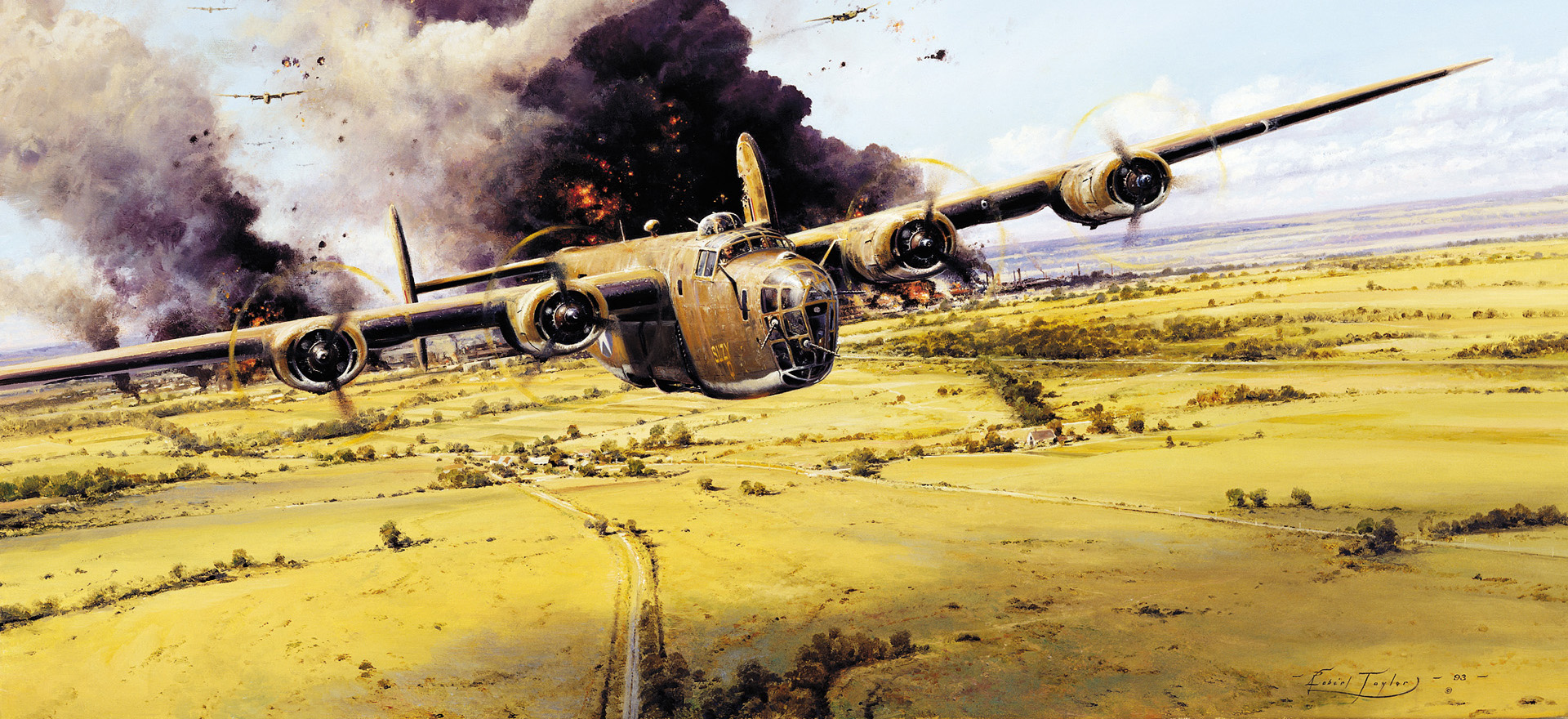

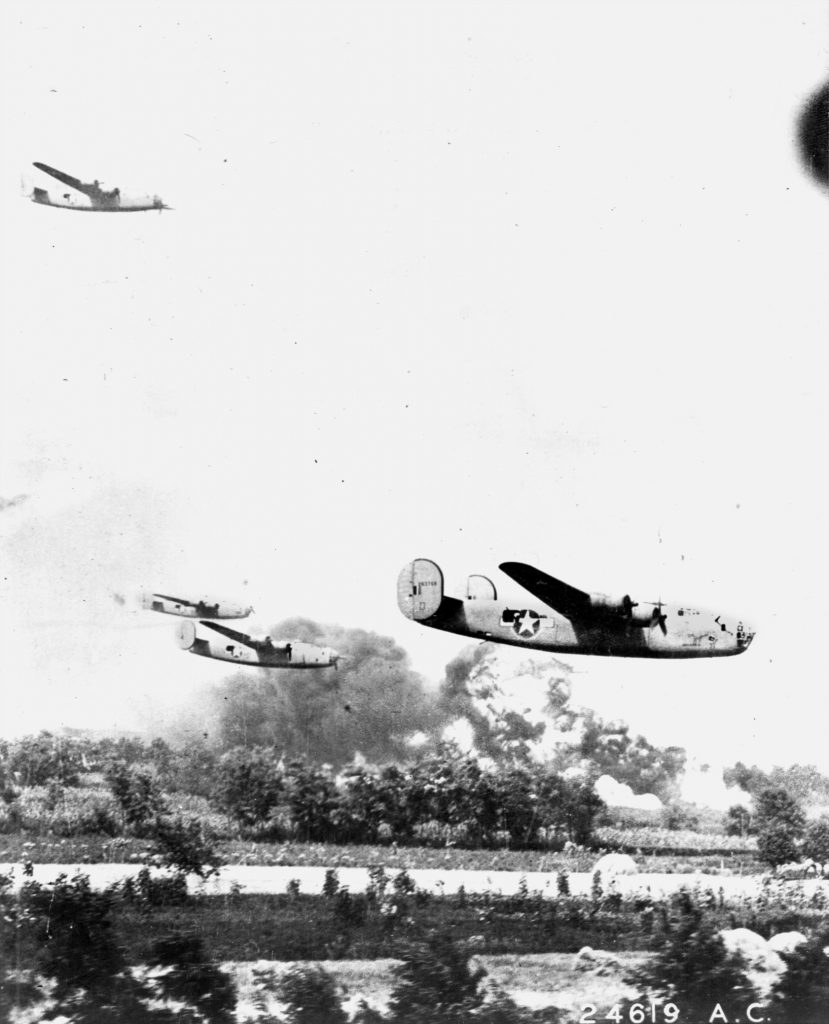

The most famous—and costly—Liberator mission of the war came when the bombers returned to Ploesti in the summer of 1943. The eight refineries ringing the city supplied Germany with 10 million tons of fuel oil a year, meeting a third of Luftwaffe and Panzer Corps needs. Because Germany possessed virtually no oil of its own, Allied planners believed that if the refineries could be destroyed, the enemy’s war-making capacity would be seriously crippled. Operation Tidal Wave was painstakingly planned by a team led by Colonel Jacob Smart as a rooftop-level assault to minimize the need for a return mission. Such an approach, it was reasoned, would enhance the bombing accuracy and reduce the effect of enemy antiaircraft batteries.

Aircrews spent several weeks maneuvering their 60,000-pound B-24Ds a few feet above the scorching desert around Benghazi on the Libyan coast. Though the plan was a bold one, Smart and his planners believed there was a better than average chance of success for the mission. But they were working with erroneous information. Allied intelligence had reported that Ploesti was lightly defended by flak guns manned by Romanians whose hearts were not fully in the German cause.

In fact, the local military commander, Colonel Alfred Gerstenberg, was a diehard Nazi who had turned Ploesti into one of the most heavily defended cities in Europe. Almost 300 deadly 88mm flak guns, 20mm and 37mm rapid-fire cannons, hundreds of heavy machine guns, and barrage balloons ringed the target area. A flak train was stationed there, and half a dozen fighter squadrons were based nearby. All were manned, not by reluctant Romanians, but by highly trained Germans. Early-warning systems extended all the way to Axis-occupied Greece to give Gerstenberg an early alert about any threat to Ploesti.

Unaware of what was waiting for them, the Americans made final preparations at Benghazi. Crews were briefed, and 178 Liberators were fueled and armed. The five bomb groups taking part were the 44th, 93rd, and 389th of the Eighth Air Force, and the 98th and 376th of the Ninth Air Force’s Ninth Bomber Command. The mission leader was 43-year-old, Pennsylvania-born Brig. Gen. Uzal G. Ent, a 1924 West Point graduate and highly decorated commander of the Ninth Bomber Command.

At dawn on Sunday, August 1, 1943, the B-24s began thundering along the Benghazi runways on their seven-hour, 2,400-mile mission. They climbed northward across the Mediterranean. Things went wrong from the start. A Liberator crashed and burned on takeoff, killing its 10-man crew, a second plane flew into the sea, and another jettisoned its bombs and crashed after being attacked by a Messerschmitt 109 fighter. As the bombers rendezvoused, 10 more B-24s had to abort and return to base with engines fouled by the desert sand.

The strike force was to head northward to the island of Corfu off the southwestern coast of Albania and then swing northeastward toward Romania. Near Corfu, the lead bomber, Wongo-Wongo, piloted by Lieutenant Brian Flavelle, inexplicably began pitching violently. After standing abruptly on its tail, it shuddered, flipped over backward, and plummeted into the Ionian Sea. No one knew what had happened because radio silence was being observed.

As the B-24s crossed the Albanian mountains, unexpected cloud cover and wind shear split the formation. The plan to have all five bomb groups hit their targets simultaneously was falling apart. A navigation error resulting from the misreading of a checkpoint diverted two of the groups toward Bucharest. The error was eventually corrected, but the new flight path was bringing the bombers toward the densest flak corridor. German intelligence, meanwhile, had deciphered a “don’t shoot” radio message to Allied naval units, and Gerstenberg’s gun crews at Ploesti were ready. The five Liberator groups would hit the target area in three waves instead of one, and they would be approaching from directions unfamiliar to them. Operation Tidal Wave was heading for disaster.

The 22 Liberators of Lt. Col. Addison E. Baker’s 93rd Bomb Group were the first to arrive at Ploesti. Piloting the lead plane, Hell’s Wench, the tall, stern-jawed Baker drove hard for the target city as the bombers tightened formation and skimmed 50 feet above farm fields. All hell soon broke loose as German guns opened up. Machine guns and flak batteries hidden in haystacks poured fire into the sky and more barrage balloons rose. The “Traveling Circus” bore on, but several bombers began trailing smoke, erupting in flames, and going down. Hell’s Wench hit a balloon cable, took several hits, and eventually crashed in flames. There were no survivors, and Baker and his co-pilot, Major John L. Jerstad, were awarded posthumous Medals of Honor.

Fifteen minutes behind the “Traveling Circus,” the final two formations—Colonel Leon Johnson’s “Eight Balls” 44th Group and the “Pyramiders” of Colonel John R. “Killer” Kane’s 98th Group—made a correct turn and headed for Ploesti on course. The bombers pressed through a curtain of fire to their targets, but the losses mounted. One after another, burning B-24s fell. Johnson lost nine of his 16 planes, but he and Kane pressed on staunchly. “It was like flying through hell,” Johnson reported. “It was indescribable to anyone who wasn’t there. We flew through sheets of flame, and airplanes were everywhere, some of them on fire, others exploding.”

Johnson and Kane, who later rose to four-star rank, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their intrepidity. Another posthumous Medal of Honor went to Lieutenant Lloyd D. “Pete” Hughes of the 389th Bomb Group, who dropped bombs squarely on target while his doomed B-24 was burning fiercely. It was the only single engagement in World War II in which five Medals of Honor were awarded. The five bomb groups received Presidential Unit Citations.

A 389th Bomb Group squadron led by Captain Philip Ardery, who had flown on the first Ploesti raid, was the last to drop bombs after plunging into a cauldron of greasy black smoke and pillars of flame. “Already the fires were leaping higher than the level of our approach,” he reported. “From the target grew the column of flames, smoke, and explosions, and we were headed straight into it. As we were going into the furnace, I said a quick prayer. During those moments I didn’t think that I could possibly come out alive.” A total of 167 bombers dropped 311 tons of bombs on the refineries.

Once past Ploesti, the surviving Liberators were ambushed by 125 German fighters, and more went down in flames. Seven crippled bombers limped to neutral Turkey, where the crews were interned; 19 landed in Sicily, Malta, or Cyprus; some failed to reach Libya and fell into the Mediterranean, while 92 battered B-24s made it back to Benghazi. The casualty toll for the mission, one of the costliest of the war, was 532 killed or wounded.

Operation Tidal Wave knocked out about 42 percent of Ploesti’s refineries for six months, but repairs were made and delivery rates for refined crude oil were unaffected. Ploesti remained a strategic magnet for the USAAF, and many more B-24s returned there. Seventeen more missions were mounted, with the loss of more than 200 bombers and more than 2,000 crewmen. The refining capacity was reduced by 80 percent before the end of the war in Europe, and Soviet troops overran Ploesti in late August 1944.

Liberators under American and foreign colors played an extensive and versatile role in the air war as the Allies gradually gained the upper hand during the second half of the global conflict. The U.S. Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces continued to equip new groups with B-24s. There were 2,000 of them in service by April 1944, and the number peaked at 2,685 that August. Global B-24 frontline strength reached 6,000 in September 1944. By May 1945, there were 1,500 Liberators in action with the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces. They gave sterling service all over the globe, from Northern Ireland to the Azores, from Gibraltar to Burma, from India to China, from Rabaul to the Indian Ocean, and from Borneo to Okinawa.

Modified as tankers, B-24s carried fuel over the “Hump” from India to China, while others joined the great silver fleets of B-29s in their punishing firestorm raids on Japan in 1944-1945. The number of frontline B-24s in service in the Pacific peaked at 992 in May 1944. High-tailed, sophisticated, lengthened versions of the Liberators, PB4Y-2 Privateers, entered U.S. Navy service in January 1945. Flying from Hawaii, Tinian, Midway, and the Philippines, they served as ocean patrol bombers and Marine Corps transports. Twenty-six of them were transferred to RAF Transport Command.

Of all the B-24s that wore the red-white-and-blue roundel of the RAF during the war, the most famous was Commando (AL-504), the personal transport of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

During his many long, hazardous journeys, he flew in it to meet Soviet Marshal Josef Stalin in Moscow, to Tripoli to inspect the Eighth Army, to confer with President Franklin D. Roosevelt at Casablanca and Cairo, and to Ankara for talks with Turkish President Ismet Inonu.

A total of 45½ U.S. bomber groups flew B-24s in World War II, compared to a maximum B-17 force of 33 groups. When the European war ended in May 1945, the production of Liberators stopped and orders for 5,168 B-24N variants were canceled.

Author Michael D. Hull has written for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.