By John Walker

No foreign army in the 5,000-year history of Japan had ever successfully conquered Japanese territory. In late 1944, American war planners were about to challenge that statistic on the tiny Pacific island of Iwo Jima. Coveted by both sides for its strategic airfields, the eight-square-mile chunk of volcanic ash, stone, and sand was inarguably Japanese soil, only 650 miles from Tokyo. Moreover, the island served as a vital early warning station against American bombing missions against the home islands.

Beginning in the summer of 1944, new, long-range American Boeing B-29 Superfortresses based on the Mariana Islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam had pounded the Japanese homeland. Iwo Jima lay midway between Japan and the Marianas, and the American Air Force hoped to use the tiny island as a forward base for fighter aircraft that could accompany the big B-29s on their long bombing runs of the Japanese mainland. In addition, the U.S. Navy wanted to use the island as a staging area for the inexorable Allied advance on Japan.

Kuribayashi’s Defense

Fully expecting an imminent invasion, Japanese imperial headquarters ordered Iwo Jima’s commander, Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, to delay the Americans as long as possible, inflict as many casualties as he could to erode their will, and buy precious time for the home islands to prepare for the looming invasion. A shrewd and experienced strategist who had learned from the earlier island campaigns in the Pacific, Kuribayashi abandoned the failed defensive tactics employed by his predecessors in the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana Islands. His forces would eschew suicidal banzai charges and not attempt to destroy the invaders at the water’s edge. Instead, they would defend the island in depth from expertly camouflaged positions with mutually supporting and interlocking fields of fire, thereby making the best use of Iwo Jima’s harsh terrain and the Japanese troops’ fighting skills. After constructing 11 miles of fortified tunnels that connected 1,500 rooms, artillery emplacements, bunkers, ammunition dumps, and pillboxes, the 21,000 Japanese defenders could fight almost entirely from underground. Colonel Baron Takeichi Nishi’s tanks would be used as camouflaged artillery positions.

Because the tunnel linking it to Iwo Jima’s northern sector was never completed, Kuribayashi organized the southern area’s defense around Mount Suribachi as a semi-independent sector while the main defensive zone was built in the north. Hundreds of hidden artillery and mortar positions meant that every part of the island was subject to Japanese fire. Kuribayashi also received a handful of kamikaze pilots and planes to use against the enemy fleet. Surrender was forbidden by imperial decree; the defenders and their commander fully expected to die on the island. Each Japanese soldier was urged to kill 10 Americans before he himself was killed.

Planning the Assault on “Sulfur Island”

On October 3, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) ordered Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, to prepare for the seizure of Iwo Jima early the next year. The amphibious assault upon Iwo Ima, which means “sulfur island” in Japanese, would involve a strike force that was more experienced, better armed, and more strongly supported that any offensive campaign yet mounted in the Pacific War. Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet enjoyed total domination of air and sea around the island, and the 74,000-man landing force would hold a 3-to-1 numerical superiority over the defenders. Seizing Iwo Jima would be difficult, American planners agreed, but Operation Detachment should take a week, possibly less. Indeed, the three Marine divisions that would take part in the landing were tentatively penciled in for an expected invasion of Okinawa just 30 days after the invasion of Iwo Jima.

The JCS orders contained a contingency clause: Nimitz must continue to provide covering and support forces for General Douglas MacArthur’s ongoing liberation of Luzon. After the Japanese defense of the Philippines proved tougher than anticipated, the Iwo Jima attack was delayed a month, a grace period that Kuribayashi put to maximum advantage. He requested and received additional assistance from several of Japan’s best fortifications engineers, men with combat experience in China and Manchuria. Iwo Jima’s soft rock lent itself to swift digging, and Japanese artillery pieces and command centers were moved even farther underground. The elaborately constructed labyrinth of tunnels was also extended. Some underground positions now boasted five levels. Mount Suribachi, dominating the island at an elevation of 556 feet, eventually contained a seven-story interior structure. Kuribayashi had plenty of weapons, ammunition, radios, fuel, and rations—everything but fresh water, always at a premium on the sulfuric rock. American intelligence wrongly concluded that the island could support no more than 13,000 defenders because of the acute water shortage. As the invading Marines would soon discover, Kuribayashi commanded many more men than that.

“We’ll Catch Seven Kinds of Hell on the Beaches”

Spruance chose veterans of earlier amphibious operations for the seizure of Iwo Jima. Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner commanded Task Force 51, the joint expeditionary force, which included nearly 500 ships, while Rear Admiral Harry Hill commanded Task Force 53, the attack force. Marine Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt commanded the V Amphibious Corps (VAC), comprised primarily of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions. Spruance and Turner also asked Marine Lt. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith to come along as commander of the ground forces. A pioneer of amphibious assaults, the prickly, 62-year-old Smith agreed, but not before loudly protesting the inadequate support arrangements. To soften up Iwo Jima’s defenses, beginning on December 8, B-29 Superfortresses, B-24 Liberator bombers, and naval vessels would begin pounding the island. After 70 days, it was estimated that 6,400 tons of bombs and 22,000 shells would have been dropped on the island.

Smith, convinced that even the most impressive aerial bombardment would not be sufficient, requested 10 additional days of naval bombardment before the Marines stormed the beaches. To his surprise and anger, the Navy rejected his request “due to limitations on the availability of ships, difficulties of ammunition replacement, and the loss of surprise.” Instead, he was told, the Navy would provide a three-day preliminary barrage. “We’ll catch seven kinds of hell on the beaches, and that will be just the beginning,” Smith warned. “The fighting will be fierce, and the casualties will be awful, but my Marines will take the damned island.” Nimitz held firm—he had no more ships to send. Like the good Marine he was, Smith saluted and set out to accomplish the task.

When the preliminary bombardment of Iwo Jima began on February 16, 1945, Smith was further dismayed when he found that it did not even reach the agreed-upon level. Visibility limitations due to bad weather led to only half-day bombardments on the first and third days. Spruance told Smith that he regretted the Navy’s inability to support the Marines to the fullest but that the Leathernecks should “be able to get away with it.” Smith, who remembered the hundreds of Marine bodies floating in the lagoon at Tarawa in November 1943, was not so sure. Those earlier casualties, he believed, were the direct result of the Navy’s failure to neutralize Tarawa’s defenses. The issue at Iwo Jima, however, was not volume, but accuracy. Kuribayashi’s well-built, artfully camouflaged gun positions were scarcely affected by the naval bombardment, whatever the size or scope. Of the 915 estimated Japanese fortifications, fewer than 200 had been silenced by the preliminary fusillade—and that did not include hundreds of smaller but equally deadly strongpoints held by small groups of defenders.

“Too Late to Worry”

With a broad rocky plateau in the north and the extinct volcano of Mount Suribachi at the southern tip of the pork chop-shaped island, the only place a full-scale invasion could be mounted was on the black cinder beaches along the southeast coast. From there it was only a short distance to Airfield No. 1, but the open beaches would be vulnerable to intense fire from higher ground to the north and south. Schmidt opted to land with two divisions abreast, the 4th Division on the right and the 5th Division on the left, opposite Mount Suribachi. The 3rd Division was held as a floating reserve.

When American underwater demolition teams approached the landing beaches in lightly armed LCIs (landing craft, infantry) in a daring daylight reconnaissance on February 17, the defenders hiding in prepared positions along the slopes of Mount Suribachi were unable to resist opening fire. The frogmen and landing craft suffered serious losses but accomplished their mission, finding no mines or underwater obstacles offshore. As a bonus, many of the Japanese gun positions on Mount Suribachi now were revealed to Navy spotters.

At 6:40 am on D-day, February 19, the 450 ships that ringed Iwo Jima began a stunning close-range bombardment, blasting shells ranging from five to 16 inches in diameter. The beaches seemed literally to be torn apart. Shortly afterward, rocket-firing gunboats attacked the Motoyama plateau, while others lobbed shells at Mount Suribachi. Then, as the firing was temporarily checked and the various ships moved into their final positions, carrier aircraft and heavy bombers from the Marianas showered the area surrounding the beaches with rockets, bombs, and napalm. Ten minutes later, the naval shelling recommenced, joined by 10 destroyers and 50 gunboats that steamed as close inshore as possible in an effort to screen the approaching invasion armada.

As the naval bombardment, a creeping barrage, reached its crescendo, the landing ships lowered their ramps and the first of five assault waves emerged, 5,500 yards from shore. One LCI carried the ominous message in foot-high letters on its ramp: “Too Late to Worry.” Each wave consisted of 69 armored LVT (landing vehicle, tracked) amtracs, or amphibious tractors, which could carry 20 troopers each and scramble over coral reefs if necessary, firing their snub-nosed 75mm howitzers from the moment they crossed the line of departure.

The Marines Hit the Beaches

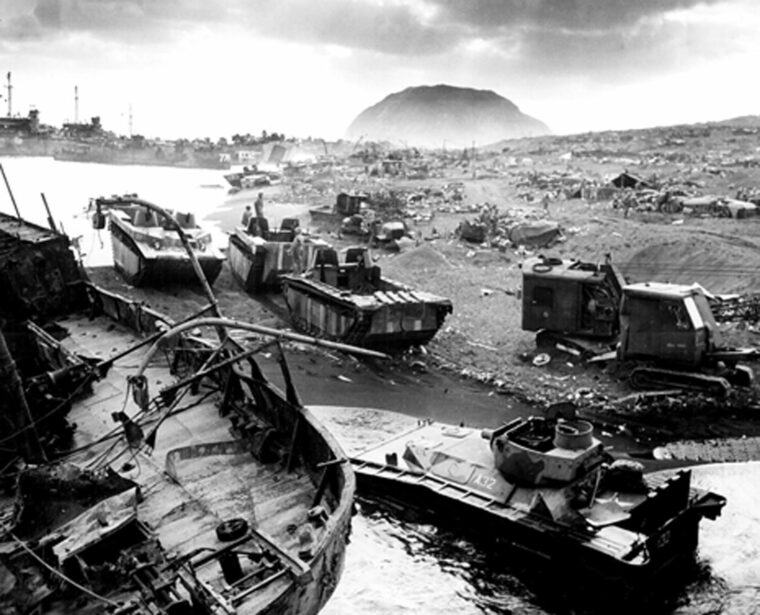

The first wave, the 4th Marine Division on the right and the 5th on the left, moved virtually unmolested toward the shore. At 8:59 am, after 30 minutes of steaming, the first amtracs hit the beach. With no coral barrier reef or killer neap tide to worry about—as at Tarawa—some 8,000 troops stormed ashore on their designated beaches right at H-hour. Light enemy fire gave some of the Marines fleeting hopes of a cakewalk, but they soon found themselves battling two unexpected physical obstacles—black volcanic ash, into which men sank up to a foot or more, and a steep terrace 15 feet high in some places, which only a few amtracs managed to climb.

A volcanic island, all of Iwo Jima’s beaches were extremely steep; with deep water so close to shore, the surf zone was narrow but violent. The soft, black sand immobilized almost all the armored mortar and rocket-firing vehicles that accompanied the Marines as they came ashore and bellied up some of the amtracs. In short order, a succession of towering waves hit the stalled vehicles before they could completely unload, filling their sterns with water and sand and broaching them broadside. The beach soon resembled a salvage yard. Once the beaches were choked with landing craft and the steep terraces clogged with infantry, Kuribayashi fired signal flares, after which the defenders opened up with heavy ordnance—hidden mortars and artillery batteries—in a rolling barrage of their own.

Undeterred, fresh waves of Marines arrived every five minutes. Despite the usual confusion, the first combat patrols pushed 150 yards inland, then 300. Enemy troops opened up, firing from rabbit holes, bunkers, and pillboxes, but slowly and desperately the Marines continued to push forward in small groups rather than as a united force. Each Japanese bunker and rabbit hole meant a fight to the death, with each enemy position supported by many others. The defenders would disappear down one hole and pop up at another, often behind rather than in front of the advancing Marines. The invaders struggled on, pouring bullets and grenades into enemy positions. Navy fire-support ships moved in closer, taking out some of the nearest Japanese firing positions with deadly accuracy. Facing 4th Division’s lines were 10 reinforced concrete blockhouses, seven covered artillery positions, and 80 pillboxes. Hidden land mines also took a heavy toll on the advancing Marines.

Among those killed in the first day of fighting was the most famous NCO of the Pacific War—Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone. After being awarded the Medal of Honor for his remarkable service during the Battle of Guadalcanal, “Manila John” Basilone had been sent on a highly publicized war bond drive back in the States. Despite being newly married, Basilone requested that he be allowed to return to active duty with the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines. He was killed by machine-gun fire on Red Beach 1 and posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

Beach masters landed early to establish order, and engineers blew up wrecked boats and LVTs to clear lanes for subsequent waves of attackers. Enterprising troops organized some of the LVTs to haul heavy equipment off the beach, allowing M4 Sherman tanks to hustle ashore. Communications remained good, and offloading continued despite the slaughter and destruction. By mid-afternoon the reserve battalions of four regimental combat teams and two tank battalions had been committed to the battle to relieve the pressure on the landing units, and by nightfall 30,000 combat troops had landed. Each team brought ashore an artillery battalion, the cannoneers suffering heavy casualties moving their 75mmm and 105mm howitzers across the soft beaches under fire. By dusk, both division commanders could report that their organic artillery was in place and delivering close fire support.

“A Nightmare in Hell”

Two miles offshore aboard the command vessel Eldorado, Turner and Schmidt were cautiously optimistic on the night of D-day. Even with 2,400 casualties, the landing force was proportionally better off than had been the case at the end of the first days on Tarawa or Saipan. Both officers expected a major banzai attack that night, but Kuribayashi refused to allow any of his subordinates to make vainglorious, suicidal charges. Some small-scale banzai attacks occurred later in the battle, but for the most part the Marines never faced large-scale frontal assaults. Each night, however, small parties of Japanese soldiers, called “wolf packs,” conducted intelligence probes, seeking gaps between units, and quietly exacted a toll on Marine outposts. By day, the defenders hunkered down and waited for the Marines to enter their preregistered killing zones, and the enforced discipline made the battle both prolonged and costly.

Time–Life correspondent Robert Sherrod described the first night on Iwo Jima as “a nightmare in hell.” Illumination shells fired from the destroyers created a surrealistic effect on the battlefield, inadvertently offering the Japanese defenders more light to fire at the Marines. Medical personnel, taxed to their limit, were not immune to enemy fire. In one sector two doctors and 16 corpsmen were killed; another medical detachment lost 11 of its 26 men. At the end of the day, some 2,312 Americans had fallen in the first 18 hours of battle. Back at the White House in Washington, President Franklin D. Roosevelt visibly shuddered when he received the first reports from Iwo Jima.

On the second morning, after a 50-minute naval barrage, the Marines moved out again. If anything, progress was slower than the first day. On the far left flank, Colonel Harry Liversedge’s 28th Regiment made repeated attacks against the approaches to Mount Suribachi backed by artillery, half-tracks, and tank destroyers but managed to advance only 200 yards the entire day. To the north, the 4th Division reached its objective of Airfield No. 1, then swung right to face the rising ground that constituted Kuribayashi’s first major line of defense. There, too, early progress soon petered out. Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines fired off a message to division headquarters: “Enemy defenses much greater than expected. There was a pillbox every ten feet. Support given was fine but did not destroy many pillboxes or caves. Groups had to take them step by step suffering severe casualties.”

General Kuribayashi sent his own message to the defenders of Mount Suribachi. “First, one must defend Iwo Jima to the bitter end,” he directed. “Second, one must blast enemy weapons and men. Third, one must kill every single enemy soldier with rifle and sword attacks. Fourth, one must discharge each bullet to its mark. Fifth, one must, even if he be the last man, continue to harass the enemy with guerrilla tactics.” That was the sort of resistance the Marines faced all across the island. It was also the last message the general sent to Suribachi. Marine engineers uncovered and severed a thick cable, isolating the mountain fortress from further contact with headquarters.

The Flag Over Mount Suribachi

On D + 3, lines remained virtually static, but the 28th Regiment, again assisted by naval and aerial bombardment, penetrated almost to the foot of Mount Suribachi. Recognizing that the mountain would be cut off early on, Kuribayashi had allocated only 1,860 men to its defense, but to its natural advantages had been added several hundred blockhouses, pillboxes, and covered guns around the base with an intricate system of caves along the slopes. As always, each position had to be taken separately using a variety of weapons: mortars, rockets, and dynamite. M4 Shermans equipped with Mark-1 flamethrowers were particularly useful for penetrating buried bunkers and cave fortresses. The Marines also flooded caves with gasoline and seawater. Meanwhile, Japanese kamikaze planes attacked fleet carrier USS Saratoga and escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea. Saratoga sustained six strikes but remained afloat. Bismarck Sea had to be abandoned to a raging fire and explosions. Some 200 sailors lost their lives.

Its defenses fatally weakened by the continued attacks, Mount Suribachi fell to elements of the 28th Marines on the morning of D + 4. An advance unit led by 1st Lt. Harold Schrier climbed to the top of the mountain and planted an American flag at 10:20 am on February 23. Sergeant Louis Lowery of Leatherneck Magazine snapped a quick photograph, but his picture was soon overshadowed by the classic photo taken a few hours later by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal of a second (larger) flag raising. Marines greeted the mountain’s capture with tumultuous cheers, bell ringing, whistles, and foghorns.

The larger battle, however, still had a bloody month to run. The troops in their attack positions down below cheered when they saw the Stars and Stripes, then continued their swing to the north. Schmidt ordered the 3rd Marine Division ashore and into place in the center of the line. He had come ashore himself to take direct control of what was the largest group of Marines yet to fight under a single command. Only 2,630 yards of enemy-held island were left, but it was obvious that every inch would be paid for dearly. With almost a year to prepare, the plateau region had been turned into an armed camp. Rockets, artillery, and mortars, including the enormous 320mm spigot mortar that lobbed 700-pound shells, bigger than anything the Marines had ever seen, were in good supply. Blockhouses, caves, and pillboxes were numerous, elaborate, and well fortified, and the defenders were well trained and seemingly in good spirits. They were prepared to hold their positions to the death, infiltrate Marine lines, or throw themselves under tanks with explosives strapped to their backs. Admiral Turner later called Iwo Jima “as well defended as any fixed position that exists in the world today.”

Clearing Out the Japanese Hand-to-Hand

The fight for the northern half of the embattled island was a toe-to-toe slugging match, with the Americans possessing the advantage of superior firepower and the Japanese using their prepared positions and excellent concealment to their advantage. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith came ashore several times to see for himself just how ugly the fighting was. He would later state emphatically, “It was the most savage and the most costly battle in the history of the Marine Corps.” An artillery officer from the 4th Marine Division lamented, “We still didn’t have an effective method of either destroying or neutralizing the defenders in a very restricted area, so it fell to the green line to get in there and dig them out in hand-to-hand combat. There must be a better way.”

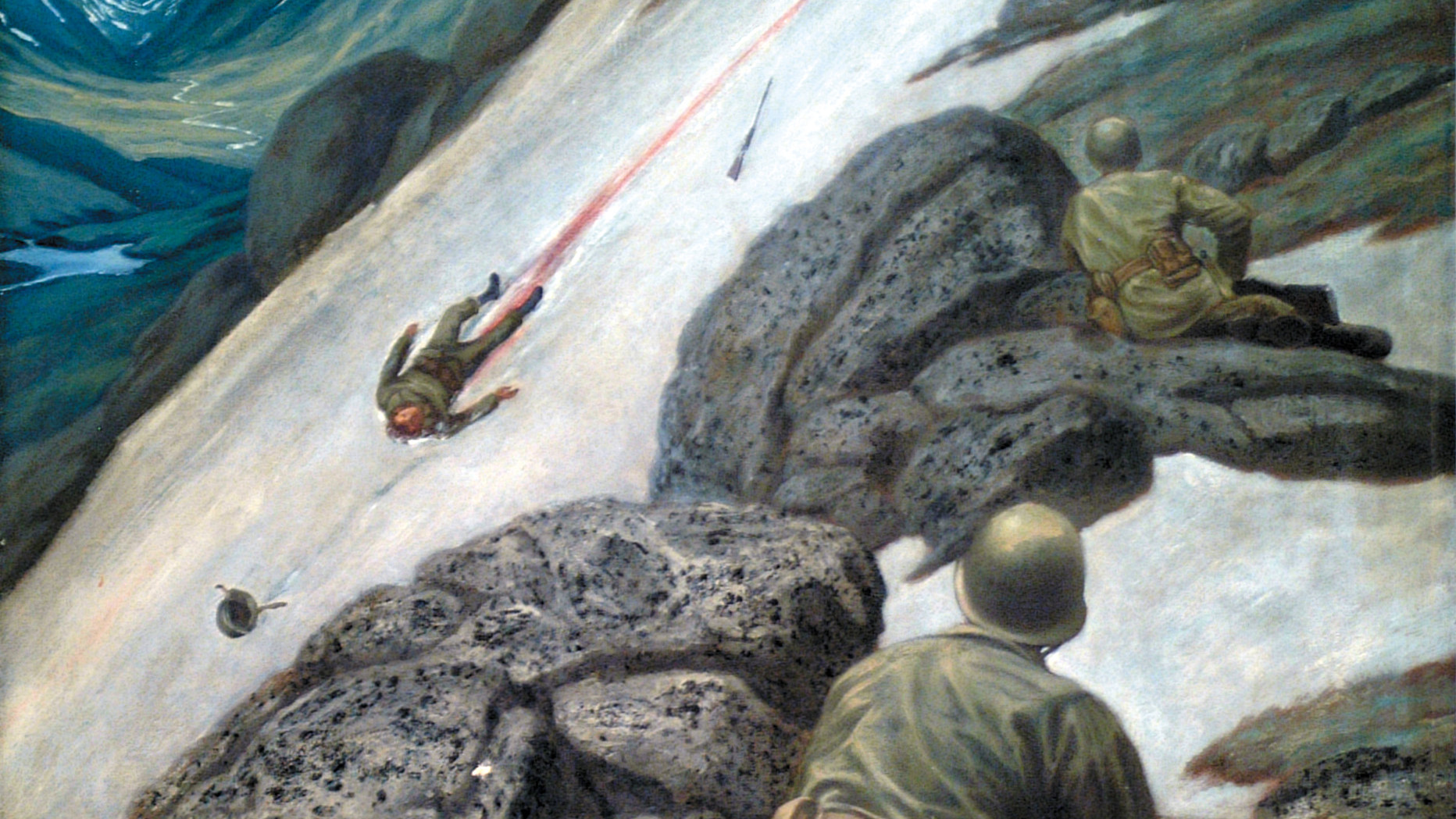

The battle for the second airfield, sited almost dead center on the island, typified the deadly fighting. There the Japanese had constructed hundreds of pillboxes, rabbit holes, and concealed emplacements that defied the concentrated firepower of the attackers. On February 24, two battalions of the 21st Marine Regiment rushed forward to take the enemy lines with bayonets and grenades—the terrain was too difficult to deploy tanks. The Japanese defenders opened fire from their concealed positions then rushed into the open to engage the attackers with bayonets of their own. Casualties soared on both sides, and the Marines, at first thrown back by the fierce counterattack, reformed and charged again.

By nightfall of the next day, they had captured the airfield and were pressing toward Minami village, with only the prospect of another bitter struggle ahead. To their right lay the formidable Hill 382, a position that became so difficult to secure that the Marines referred to it ominously as the Meat Grinder. The fighting in the days following was more of the same. The Americans had to take the higher, central part of the enemy’s lines first, and whenever the 4th or 5th Division’s units pushed ahead on their respective flanks, they were heavily punished by the Japanese who overlooked them. The problem was that the central sector’s terrain made it difficult to deploy armor or artillery or to direct naval support fire with any accuracy. The slow, difficult, and deadly task of clearing the area fell to the Marine infantry units.

Over Ten Days of Fighting

By the 10th day of the fighting, the 3rd Division’s supporting fire had been substantially increased, and forward battalions found a weak spot in the Japanese lines and poured through it. By evening Minami village, now a heap of stones and rubble, was secured and the Marines could gaze down upon the island’s third airfield. Once again, though, fierce Japanese resistance slowed the Marines’ momentum as they approached Kuribayashi’s second line of defense, and there remained many areas to secure. Its suicidal defenders fiercely held Hill 382 for two more days, and Hill 362 in the west was equally difficult.

The whole operation was taking much longer than the 10 days General Schmidt had estimated it would take, and the Marines were tired and depleted; some units were down to 30 percent of their original strength. On Sunday, March 5, the three divisions regrouped and rested as best they could in the face of Japanese shelling and occasional infiltration. On that day, too, the Marines watched as a B-29 with a faulty fuel valve returning to Tinian after a raid on Tokyo made an emergency landing on Airfield No. 1.

For the Japanese, the situation was growing increasingly grim. Most of Kuribayashi’s tanks and guns and over two-thirds of his officers had been lost, and his soldiers had been reduced to strapping explosives to their backs and throwing themselves under American tanks. The Marines continued moving forward relentlessly, however, forcing a gradual breakdown in Kuribayashi’s communications system. Left to their own devices, individual Japanese officers tended to revert to the offensive, exposing the much diminished Japanese ground forces to the weight of American firepower. One attack by 1,000 naval troops on the night of March 8-9 was easily repulsed by units of the 4th Marine Division, with Japanese losses of over 800 men.

Like “Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg”

On the afternoon of March 9, a patrol from the 3rd Marine Division reached the northeastern coast of Iwo Jima and sent back a sample of salt water to prove that the enemy’s line had been cut in two. There was no stopping the American advance now, but there was no sign of Japanese surrender either. The only indication of their grave situation was an increasing number of small banzai charges. Kuribayashi’s reports described the deteriorating situation. On March 10, he wrote, “Bombardment so fierce I cannot express nor write of it here.” The next day, he reported, “Surviving strength of northern districts (army and navy) is 1,500 men.” Then, on March 15, he wrote: “Situation very serious. Present strength of northern district about 900 men.”

On March 14 the Americans, believing all organized resistance to be at an end, declared Iwo Jima occupied and raised the Stars and Stripes. Yet, underground in their warren of caves and tunnels the Japanese lived on. Kuribayashi told survivors on March 17: “Battle situation come to the last moment. I want surviving officers and men to go out and attack enemy until the last. You have devoted yourself to the Emperor. Do not think of yourselves. I am always at the head of you all.”

The same day as Kuribayashi’s defiant last message, Admiral Nimitz declared Iwo Jima “officially secured.” Marine divisions had effective control of the entire island, but it had come at a terrible price: 24,127 casualties, of whom 4,189 were dead and 19,938 wounded in less than 27 days of combat. “Among the Americans who served on Iwo island,” Nimitz said, “uncommon valor was a common virtue.” Howlin’ Mad Smith left that same day, flying out on Nimitz’s personal four-engine Douglas transport. At a press conference at Pearl Harbor, the Marine general told a standing-room-only crowd of reporters, “We showed the Japanese at Iwo Jima that we can take any damn thing they’ve got. Watching the Marines cross the island reminded me of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg.”

Clearing out pockets of organized resistance with tanks, demolition teams, rifle fire, and flamethrowers took until March 26, the day that Schmidt announced that the operation was over, a full 34 days after the landing. Just a few hours earlier, a well-armed force of 350 Japanese had infiltrated Marine lines and fallen upon a rear encampment of support troops, inflicting 200 casualties in the confusion of darkness before being overwhelmed and snuffed out. First Lieutenant Harry Martin of the 5th Pioneers, who led the defense, was killed overrunning a Japanese machine-gun position. He was later awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor—one of 27 awarded for Iwo Jima, the most of any single battle in Marine Corps history. It was rumored that Kuribayashi himself had led the final murderous attack, but his body was never found.

Schmidt turned the island over to troops of the U.S. Army’s 147th Infantry and began re-embarkation of his own men. Japanese stragglers continued to be captured long after the battle was over. Of the defenders, only 1,083 survived the fighting.

Success at a High Cost

News of the savagery and casualties of Iwo Jima stunned the American public. The Hearst newspaper chain demanded that Nimitz and Spruance be replaced by MacArthur, “a general who looks after his troops.” But there was hardly time for recrimination; the invasion of Okinawa began just four days after Iwo Jima fell. That campaign would prove equally bloody and savage. Ahead, presumably, lay the invasion of the Japanese home islands themselves.

Seizing Iwo Jima achieved all the strategic goals put forth by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. American B-29s could henceforth fly with less reserve fuel and a greater bomb payload, knowing that Iwo Jima would be available as an emergency field. Island-based fighters escorted the Superfortresses to and from bombing runs on Honshu. For the first time, all the Japanese islands were within bomber range, including Hokkaido. Was it worth the staggering cost in human lives? The 2,400 Air Force pilots who landed on Iwo Jima between its capture and

V-J Day had no doubts. Said one, “Whenever I land on this island, I thank God and the men who fought for it.”

For 36 days in early 1945, a total of 74,000 U.S. Marines had fought a vicious battle of attrition against 21,000 unyielding Japanese defenders for control of one tiny, seemingly impregnable Pacific island. In just 36 days of combat, 25,851 Americans, fully one-third of the assault forces, had become casualties. Of those, 6,821 were killed, died of wounds, or were missing in action. One historian later described the American attack at Iwo Jima as “throwing human flesh against reinforced concrete.” Against unimaginable odds, American flesh had won out over Japanese concrete. Uncommon valor indeed.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments