By William McPeak

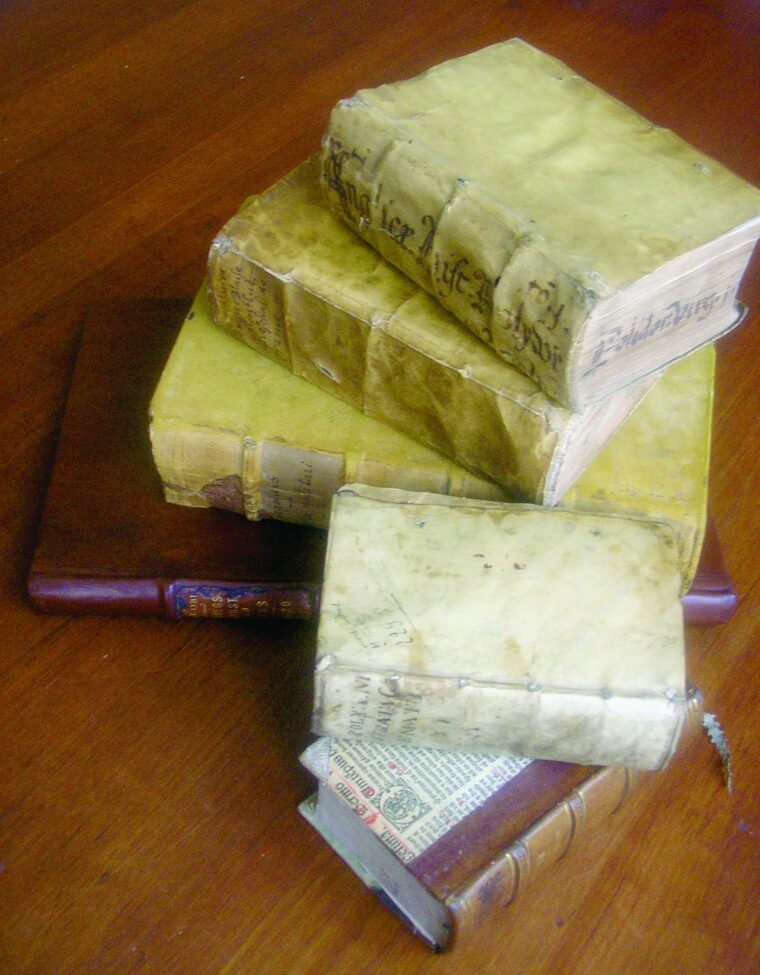

The special packaging of the printed word between compact durable covers and a stitched spine—the book—is one of humanity’s greatest and most enduring achievements. It is also a fertile field for modern collectors. Some of the earliest and most important examples of European book printing still survive, mostly because of how well made early printed books, called “incunab-ula”—literally, cradle books—were in the mid-15th century. The incunabula were relatively cheap compared with manuscripts, or handwritten books. The best-printed books were often embellished for the upper classes with expensive tooled-leather bindings. In the late 15th century, less expensive and practical vellum (degreased calf skin) bindings appeared. Into the next century, these often had cardboard or thick paper backing covered by vellum to further lower the books’ prices. As time went on and the sheer volume of printed books grew, these earlier books tended to become cheaper to buy and collect.

Today, such books are increasingly sought after. War was everywhere in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, and the analysis of strategy and tactics of ancient military men as well as advances in martial technology—gunpowder heading the list—were popular subjects for books. The earliest and rarest printed militaria are illustrated books on the subject of ordnance and the machines of war. The first of these was the De re militari by Roberto Valturio, published in Verona, Italy, in 1472. The book contained 82 woodcuts of various cannons, carriages, siege engines, portable towers, even hand-held firearms. Later editions of Valturio’s work and other books dealing with weaponry added more up-to-date weapons and other technical innovations.

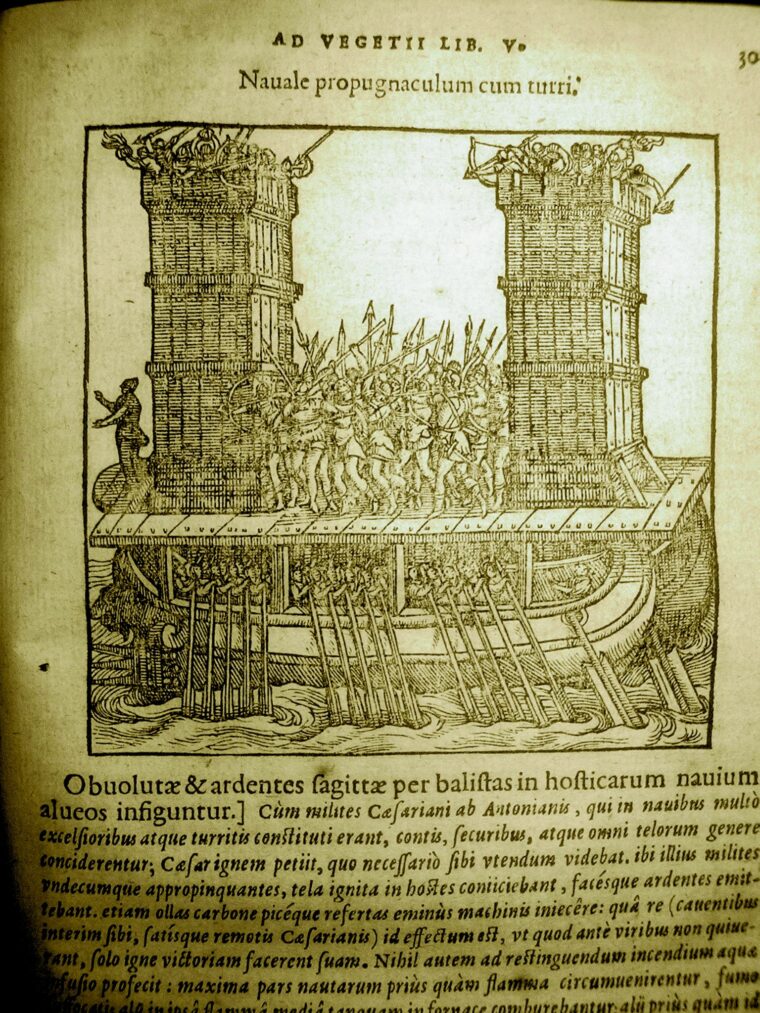

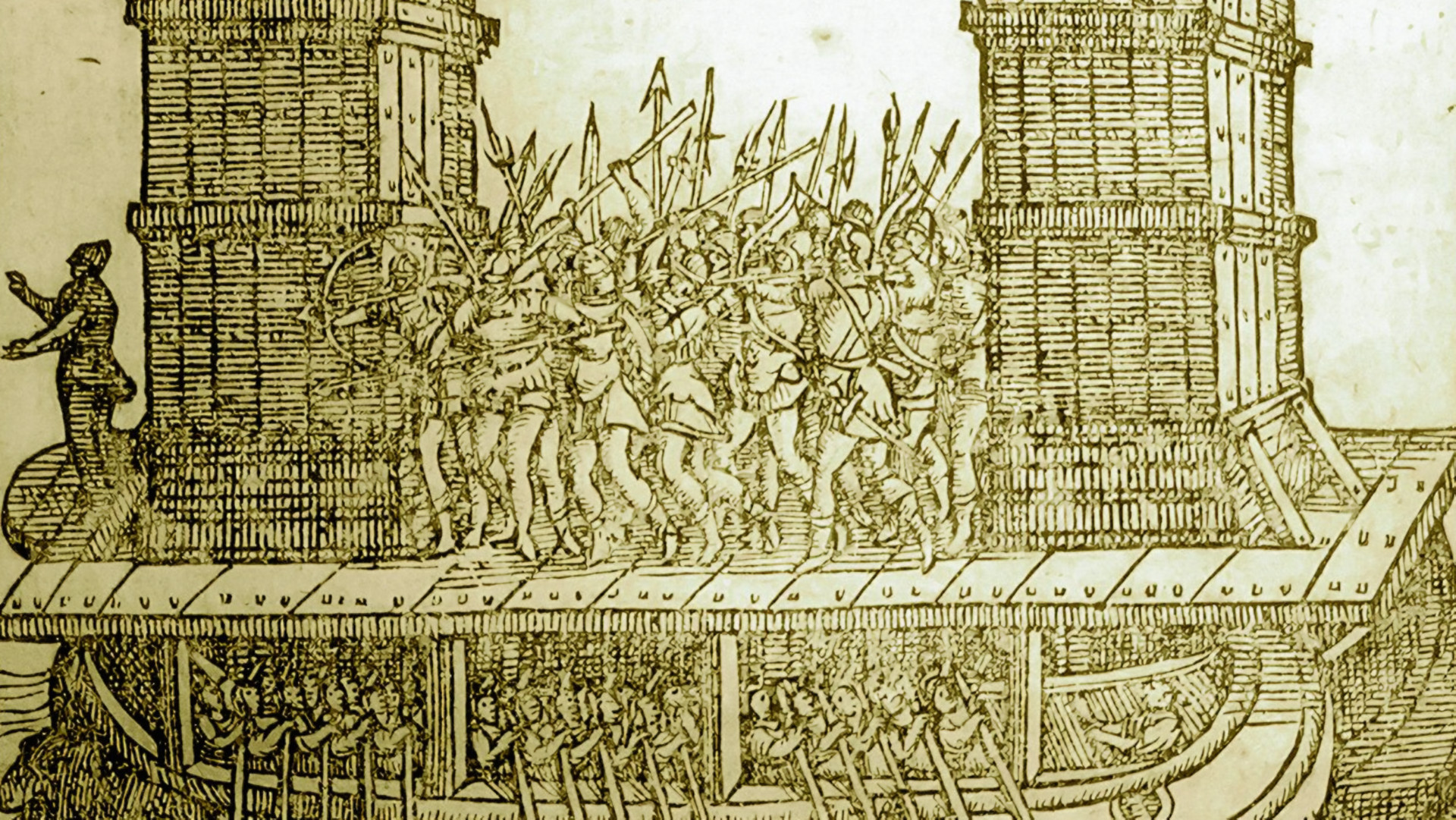

The histories and technical works of ancient military authors were already in print in the latter half of the 15th century. Roman noble Publius Flavius Vegetius was the most popular with his broad narrative of the Roman army and its downfall. More technical ancient works were also carefully studied, particularly with regard to practical advice on training and drilling. Vegetius’s work was first printed at Utrecht in 1475. A few years later he was joined by other ancient authors, including Roman military governor Sextus Julius Frontinus and Greek historians Aelianus Tacticus and Polybius. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, more obscure ancient military authors were added to other editions of the omnibus book, still entitled De re militari.

The history of warfare was joined by insights into ancient cultures and geography. Favorite authors included Greek general Thucydides, who wrote on the Peloponnesian War; Polybius, who wrote on the Third Punic War and the Sack of Carthage; and Roman historian Titus Livius Livy, who produced a massive history of Rome. Livy’s astonishing labor has been likened to writing a 300-page book each year for 45 years. Roman senator and governor Cornelius Tactius’s Annales dealt with the late imperial period and its warfare. Most popular by far was the work of another Roman—Julius Caesar—whose far-reaching military campaigns transformed the republic into an empire. His personal account of his campaigns, starting with the Gallic Wars and the Roman Civil War, extended to the Alexandrine, African, and Hispanic wars. They are all known collectively as the Commentaries, and are familiar to every high school Latin student. The format was emulated by 16th-century authors, the two most famous being the Commentaries on French Military, the Late Italian Wars and the French Wars of Religion by career soldier Blaise de Monluc and Discours by French field commander Francois de al Noue.

Ancient military history was also very much about military leaders. Snatches of biography in ancient histories gave rise to full biographies. Alexander the Great was perhaps the first commander singled out for biographical treatment by authors, the best known of whom was the Roman historian Curtius Rufus. Included in this new field was Tacitus’s writing about the life of his father-in-law, Imperial general Gnaeus Julia Agricola. A collected format was a convenient means of providing varied biographies for purposes of comparison and contrast. The first and most famous of these was Greek historian Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. It was first printed in 1472 and was reprinted many times afterward. Plutarch also wrote one of the best full biographies of Alexander the Great.

In the 16th century, books on ancient militaria made way for those on medieval and contemporary military history, with a sprinkling of up-to-date military topics such as innovations in military technology. By then, the look of books had been considerably dressed up. Title pages had ornate borders and subtitles, with fancy large initial letters (a holdover from manuscript writing) to start each chapter or section. Partial and full-page woodcuts (pictures printed from carved wooden blocks) illustrated different subjects, and maps and oversize pictures were included as foldouts. Military topics were particularly favorable for these innovations, which also saw the rising popularity of the first pocketbooks—books that were only four or five inches high. A few additional Greek military writers were translated during this period, including the cavalry officer Polyaenus, whose Strategems of War was edited and published in a combination of the original Greek and Latin by Swiss scholar Isaac Casaubon in 1589 as a small pocketbook.

The 16th and early 17th centuries were a period of major conflicts, and changes in military technology were reflected in the books of the time. Warfare was almost constant: the continual threat of Turkish invasion, the Italian Wars of the French kings against the Austrian Hapsburg emperors, the German and French religious wars, and the Dutch Wars of Independence against the Spanish. The latter became conjoined to the terrible Thirty Years’ War in 1648 (making the Dutch struggle against the Spanish an eighty years’ war). These followed one another throughout the century and were the subjects of various histories and commentaries.

Like ancient military histories, these later varieties were sprinkled with bias. Early political and military histories were particularly prone to exaggerations. Seeking favor with the English Tudor monarchs, transplanted Italian historian Polydore Vergil tinged his History of England to discredit the members of the former ruling Plantagenets. Yet there were also some incisive military analysts of the period, including the Italian historian Paolo Giovio, whose History of Our Time featured his eyewitness accounts of battles during the Italian Wars, and his countryman Francesco Guiccardini, who produced an insightul History of Italy. These and other historians imitated ancient historians in Latin style and format. Giovio had an enthusiasm for the great military men of the past, having a considerable collection of portraits of famous commanders in his home. Emulating Plutarch, he also wrote a biographical collection of past leaders paralleled with recent Italian leaders; it was called Tributes to the Military Virtues of Illustrious Men. He wrote several extended biographies as well, including one on the Spanish “Great Captain” of the early Italian Wars, General Gonsolvo de Cordoba.

Practical books reflecting evolving military science began appearing in the late 16th century. These dealt with new technical theories and military exercises—tactical formations for firearms and the pike, drilling with arms, and other battle-ready training preparations. One innovative area of study was in military architecture, particularly the design of fortifications, which had been going through significant changes since the early 15th century. Another fertile area of practical theory was in the realm of ordnance, the accurate firing of cannons, which traditionally had been learned through trial and error.

In 1537, the Italian mathematician and military engineer Niccolo Fontana published his New Science, a short treatise on the mathematics of the trajectory motion of cannonball flight. Fontana was nicknamed Tartaglia, meaning “stutterer.” As a boy, he had been a victim of French savagery during the 1512 sack of Brescia, when a soldier sliced his palate with a sword, inflicting his lifelong handicap. In his book he showed that ordnance was an exact science wherein shots could be precisely aimed. Soon, practical books on gunnery were being published, and simple geometrical ranging instruments developed as applications from Fontana’s scholarly foundation.

Battlefield maneuvering had advanced dramatically from the end of the 15th century, with massed block formations of infantry pikes followed by similar arrays for firearms after the mid-16th century. The need for speed and maneuverability called for a high level of discipline in weapon handling and orderly drill. One of the early eye-opening results of this training was the defeat of heavy cavalry by the massed firepower of the matchlock long arm. The various lancer cavalries licked their wounds and revamped with the use of the first semiautomatic firearm ignition system, the wheel lock. They also practiced block formation maneuvers meant to counteract the potent firearm infantries.

Period histories chronicled these dramatic changes. But there were also a small number of conservative authors in France and England who printed treatises against the use of firearms and other innovations. Some of the latter were particularly stubborn about keeping the longbow up front on the battlefield. But the century’s various wars marked progressive field validation of effective well-executed firearm tactics.

This revolution on the battlefield influenced an innovative new book format in the early 17th century—the manual. After nearly a century of steadily evolving practices, there was a great need to render intricate battle orders and maneuvers into a simple printed format, with the bonus of technically accurate and quality illustrations. Inspired by a study of ancient tacticians on military exercises, Dutch Count Maurice combined basic arms drill with the illustrative expertise of Flemish artist and engraver Jacob de Gheyn into the first illustrated manual of arms, the historic The Exercise of Arms (1607). The book contained 117 detailed copper engravings for the firing of long arms and the proper manipulation of the pike. Wilhelm Hoffman plagiarized Maurice’s book in a reduced format in 1609. Two years later, the first full manual for cavalry, Rules for Cavalry, by Knight Hospitaler Lodovico Melzowith, appeared. This was followed almost immediately by another significant book dealing with light cavalry by Hungarian General Giorgio Basta, better known as “Butcher Basta” by the people he suppressed.

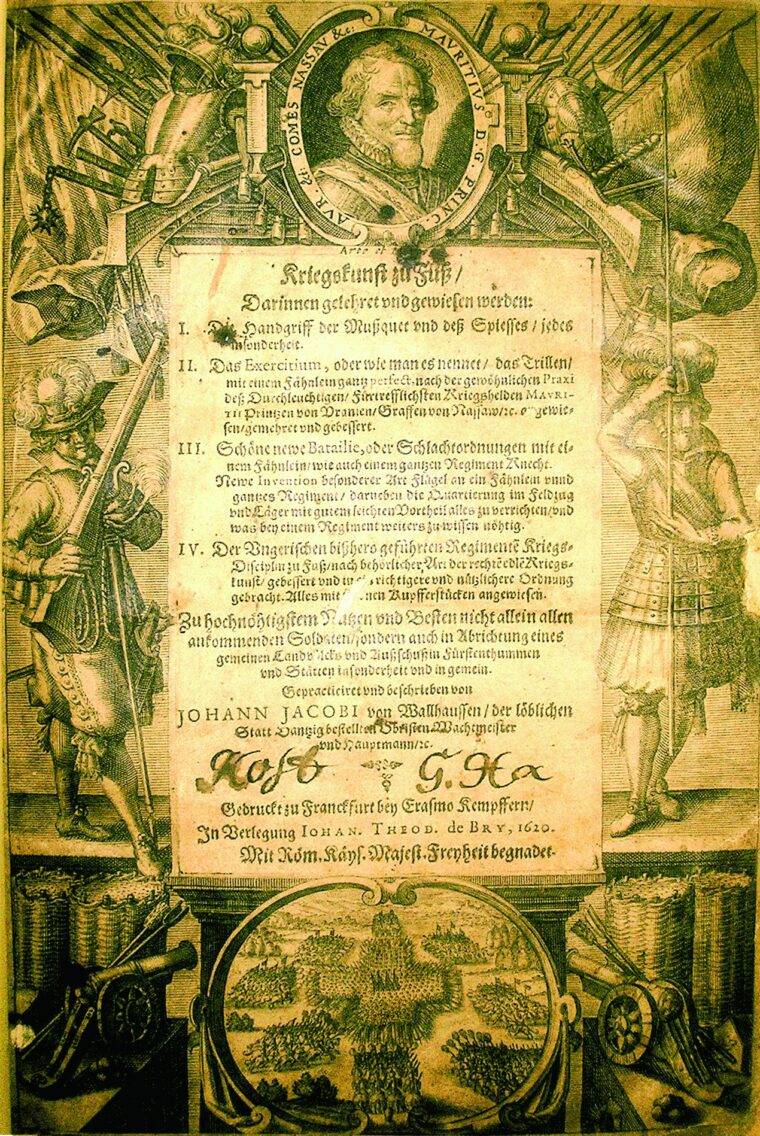

The illustrated manual took on an encyclopedic format a few years later with the concerted efforts of a veteran officer of considerable experience. Johann Jacobi von Wallhausen had served in the Low Countries under Maurice, and then had spent four years as a lieutenant colonel in the service of the Elector of Mainz before moving on to become the principal captain of the city of Danzig. Jacobi found that he had a real sense of mission in teaching military essentials, and he authored a number of military manuals. For the all-important illustrations he turned to another Flemish family of artists, the De Bry brothers. In 1615 his The Art of Infantry Warfare appeared in German, the first complete manual of infantry training and tactics with accurate illustrations. The book had foldout pages with the manual of arms for long arms and pike and also the first bird’s-eye view of infantry formations for defense against heavy cavalry. Jacobi brought out a similarly comprehensive manual for cavalry, The Art of Cavalry in 1616, and the next year he followed up with another on the pike. He published three other military works meant to be a complete compendium of military science. His comprehensive works label him the most important military writer before the Thirty Years’ War.

Having a well-stocked library—military and otherwise—was a sign of one’s level of prestige, and personal libraries grew in the 17th and 18th centuries. The auctioning of libraries became prevalent in the 18th century and reflected a rise in the worth of old books. Their worth grew steadily through the 19th century, and by the 20th century the competition for collecting historically important early printed books rose progressively. Prices also rose. Larger books are more desirable. A folio-size book—12 inches and up in height—is more valuable than an octavo, a book about eight inches high.

Early militaria books are rare. Some simple vellum-bound editions of ancient military history and commentaries printed from 1600 can still be found for $300. But specialty subjects from the 16th and 17th centuries are at a premium. Complete cutting-edge manuals of arms and tactical exercises are particularly rare. The directions and illustrations for everything from arranging troops to setting up camp often were torn out of the books for future reference. Others were simply thumbed out of existence from hard use by officers in the field, despite special battlefield bindings with wrap-around leather and a secure buckle to protect them. De Gheyn’s landmark Exercise is so rare that a first edition easily hovers above the $50,000 price range.

Military books of all sorts remain one of the most popular areas of publishing. Whether military history, weaponry, or training manuals, all had their start with the evolution of movable-type printing and the first books on militaria, the revolutionary incunabula.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments