By William F. Floyd Jr.

The series of battles that constituted the Confederate offensive against the Union army on the eastern outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, in summer 1862 would thrust a number of Union officers into the limelight. When Confederate General Robert E. Lee penned his General Orders No. 75 on June 24, outlining his strategy for the Seven Days Battle, the initiative switched from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, to Lee’s newly created Army of Northern Virginia.

One of the Union generals who would shine in those trying battles was New York native Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield. A graduate of Union College in upstate New York, Butterfield worked before the war for the freight forwarding company American Express. Butterfield, who lacked formal military training, volunteered to serve in the Union army following the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861.

On May 2, Butterfield was mustered into Federal service as colonel of the 12th New York Militia, a unit that joined Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s Army of the Shenandoah in Martinsburg, Virginia. Exhibiting considerable competence, Butterfield received a promotion to brigadier general in September. Upon transfer to the Army of the Potomac, Butterfield’s brigade shipped out from Alexandria, Virginia, for the Virginia Peninsula in March 1862 to participate in McClellan’s strategic flanking maneuver designed to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Butterfield would contribute a great deal to the Union war effort. His talent as a leader became apparent early on when he authored “Camp and Outpost Duty for Infantry,” a field manual that set forth detailed rules for setting up camp, conducting marches, and performance of duties. The War Department adopted the manual for use by the Union army.

By the third week in May, McClellan had established a strong bridgehead on the south side of the Chickahominy River. For the final push on Richmond he reorganized his army, creating two new corps. Butterfield’s brigade, which consisted of regiments from New York, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, became the Third Brigade of Brig. Gen. George Morell’s First Division of Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s newly created V Corps.

When Lee learned that the Union right flank on the north side of the river was vulnerable to attack, he issued general orders No 75 instructing his division commanders to “sweep down the Chickahominy and endeavor to drive the enemy from his position above New Bridge.”

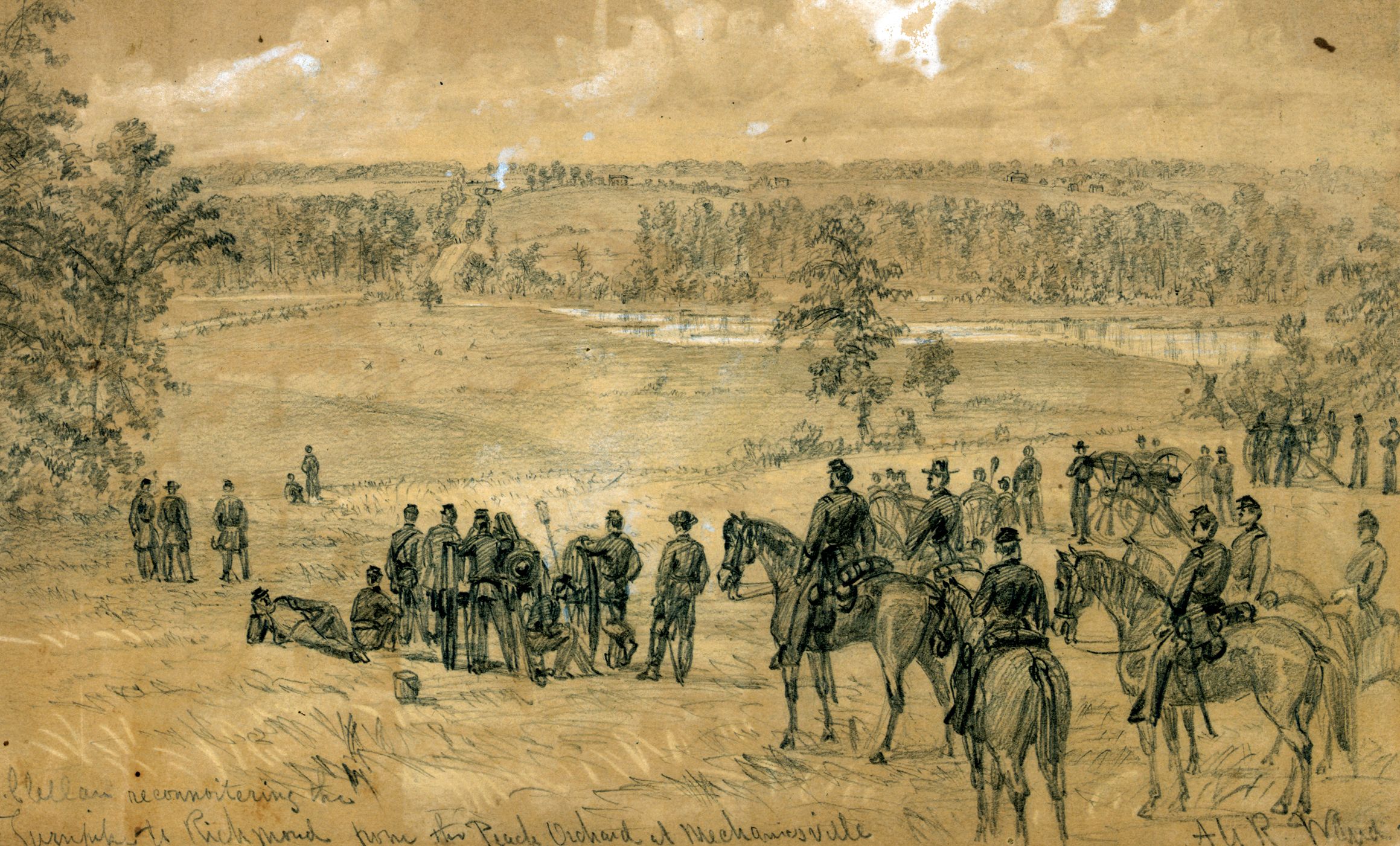

By that time most of McClellan’s troops were on the south side of the Chickahominy, but McClellan left Porter’s corps on the north side to guard his base at White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. Lee began his offensive on June 26 with an attack on Porter’s troops at Mechanicsville.

After the clash at Mechanicsville, McClellan ordered Porter to fall back to Gaines’ Mill where he would receive reinforcements. Porter’s troops established a formidable defensive position at Gaines’ Mill behind Boatswain’s Creek. Porter’s line consisted of rows of infantry behind breastworks with artillery on the high ground behind them. Porter had 26,000 Yankees with which to oppose Lee’s 57,000 troops.

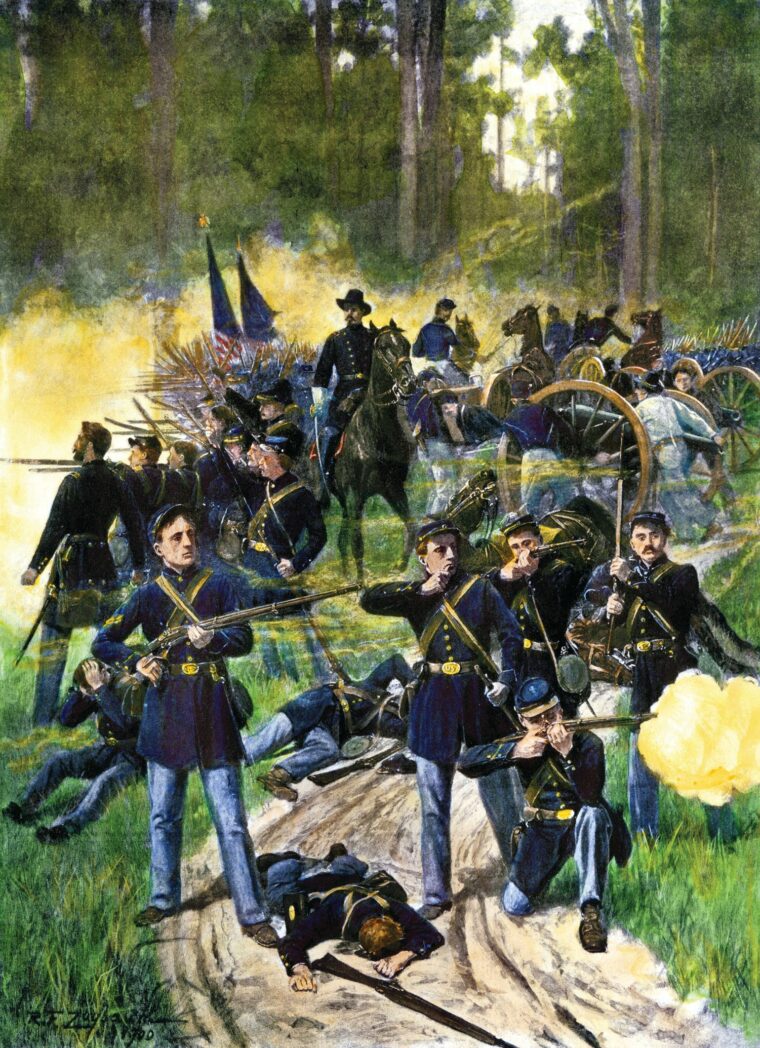

The Confederates spent the morning of June 7 getting into position for their attack at Gaines’ Mill. Butterfield’s brigade defended the extreme left of the Union line. He positioned the 44th New York and 83rd Pennsylvania regiments in the first row nearest the creek. Behind them he placed the 16th Michigan and 12th New York regiments.

The Confederates seemed determined to sweep the Federals from the field by the use of superior numbers. Throughout the late afternoon Confederate Maj. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill’s division had attacked Morell’s division, but Butterfield’s brigade had not come under attack. At 5 p.m., though, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet deployed three of his six brigades directly opposite Butterfield’s brigade.

The Confederates made a final lunge at the Union lines as darkness began to set in. At 6:30 p.m., the Confederates assailed the entire length of the Federal line with the same ferocity they had exhibited in the attack earlier in the day. Alabamians and Virginians of Longstreet’s division swept forward across open ground, entered the woods, and forded the creek under heavy fire from Butterfield’s Yankees.

Butterfield did everything he could to inspire his troops in the face of the enemy’s superiority in numbers. As the Confederates massed before them, he rode along his lines with the brigade’s colors in hand in an effort to motivate every soldier under his command. “Your ammunition is never expended while you have your bayonets, my boys, and use them to the socket!” he shouted.

Longstreet’s soldiers succeeded in bursting through Brig. Gen. John Martindale’s left regiments, which were deployed to the right of Butterfield’s troops. As the Union left began to unravel, Butterfield rushed forward and seized the colors of the 83rd Pennsylvania near the creek. Waving them aloft, he sought to rally the Keystone State soldiers. Wounded during the savage fighting, he would receive the Medal of Honor 30 years later for the valor he exhibited rallying the Pennsylvanians.

Yet his act of valor could not forestall the inevitable. Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s Alabamians overran Butterfield’s left regiments at the same time that the Confederates broke through the Union center. After the battle, Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Texas brigade received most of the credit for breaking through the Union center, but Wilcox had also broken through the Union line.

Butterfield’s star continued to rise throughout the remainder of the war. He succeeded Morell as division commander on October 30, 1862. When Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker took command of the Army of the Potomac in January 1863, he chose Butterfield as his chief of staff.

Butterfield received a promotion to major general two months later. He continued in this capacity under Maj. Gen. George G. Meade at Gettysburg where Butterfield was severely wounded on the third day of the battle. Afterwards, he took command of the Union XX Corps in Hooker’s Army of the Cumberland, which was transferred to western theater.

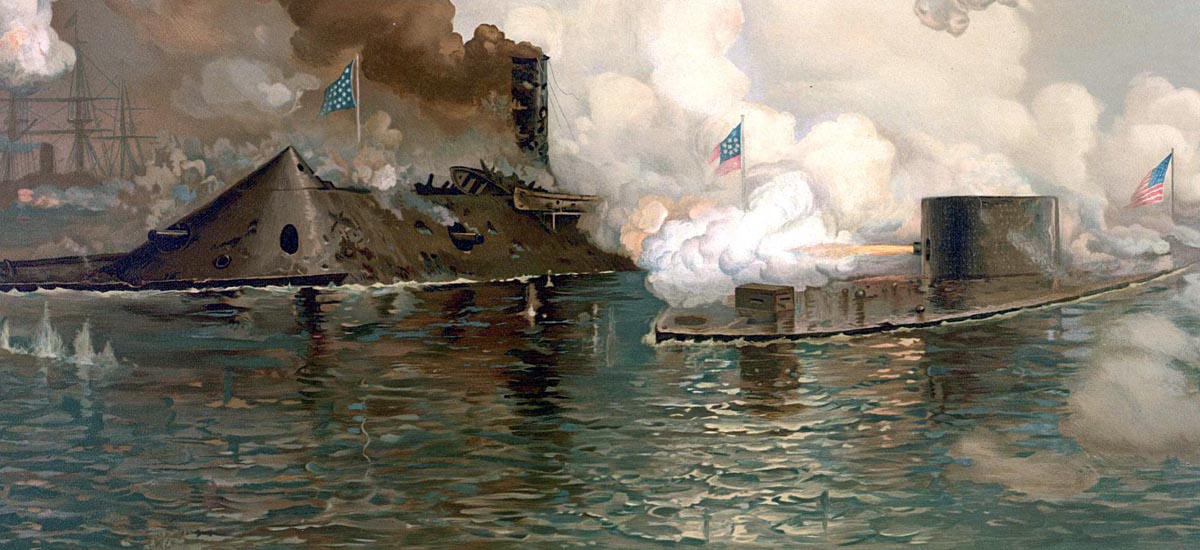

Butterfield is perhaps best remembered as the composer of the bugle call “Taps,” which he composed at Harrison’s Landing at the close of McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. The decorated war hero, author, and composer died in 1901 at the age of 70 and is buried at West Point.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments