By Arnold Blumberg

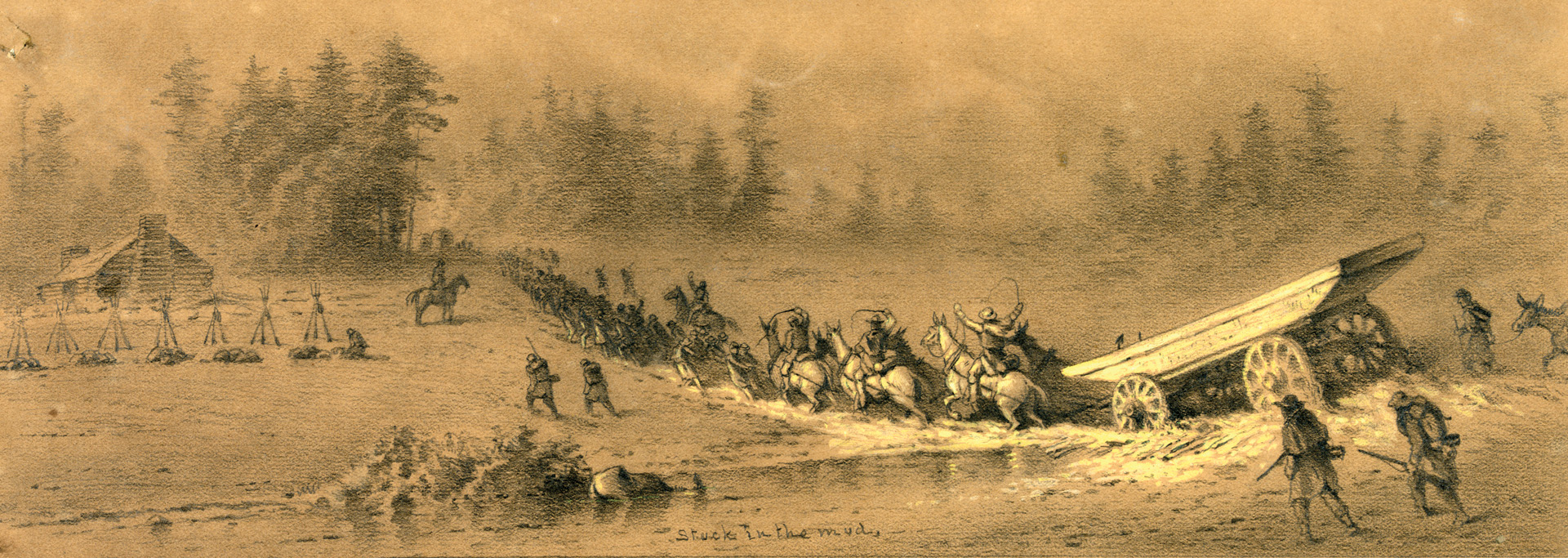

The Union officer saw it quite clearly across the Rappahannock River: a hand-painted sign held up by a Rebel soldier that read, “Burnside and his pontoons stuck in the mud. Move at 1 o’clock, 3 days’ rations in haversacks.” The blue coated officer marveled with professional interest that at least one Southerner seemed to have full details on the latest movement of the Army of the Potomac. What the officer witnessed was one of many examples of enemy jeers and taunts directed at the Yankees as they were mired in the Virginia mud under rain-filled skies while on what would later be known as Burnside’s Mud March. The attempt to steal a march on Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commander General Robert E. Lee was a floundering and ultimately futile four-day trek that began on January 20, 1863, and was designed to get around Lee’s western flank.

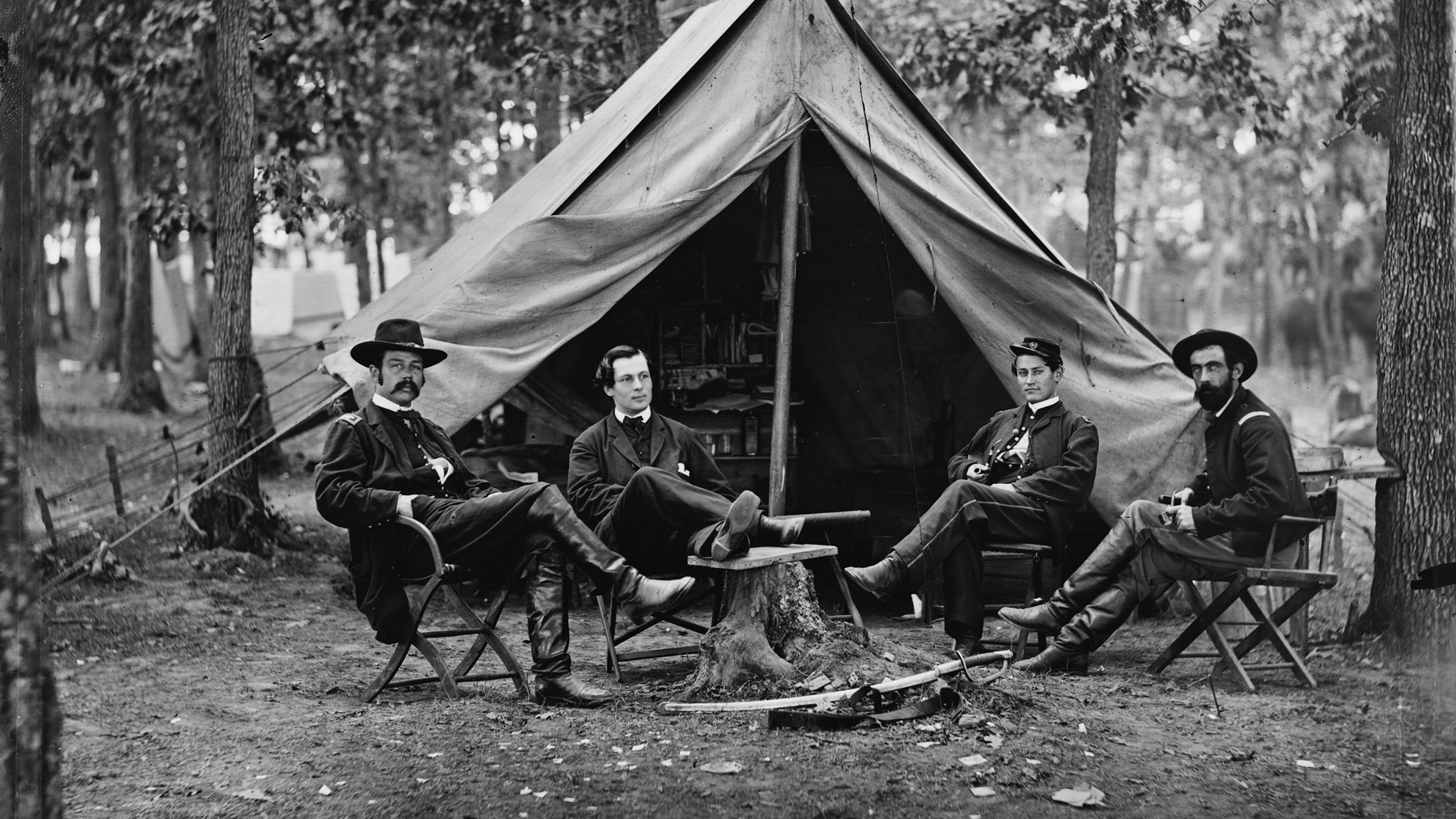

The Mud March, together with Burnside’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg in mid-December 1862, prompted the removal of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside from command of the Army of the Potomac. His replacement, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, immediately set to work to revitalize the army by improving its administration. One Hooker appointment, which was as important as any he made during his reorganization effort, was naming Colonel George Henry Sharpe, the officer who noticed the Rebel sign describing the Union Army’s movements during the Mud March, as his chief of intelligence.

For the first two years of the war, Union intelligence gathering relied on Allen Pinkerton. As the Army of the Potomac’s spymaster under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, Pinkerton and his agents occasionally penetrated Confederate-held northern Virginia. But their chief duty was the interrogation of captured enemy soldiers and deserters. Unfortunately, serious problems existed with Pinkerton and his organization, the most notorious being its penchant for grossly inflating Confederate troop strength. Often Pinkerton’s estimates ran double the actual size of the Confederate army in the eastern theater.

Things did not improve from the standpoint of intelligence gathering under Burnside, who was the second commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside had only one secret service employee, John C. Babcock, when Pinkerton left the job after the Antietam Campaign. Although Babcock was a skilled interrogator and an order-of-battle expert, Burnside failed to properly use him. The result was that the intelligence service within the army functioned poorly since it focused solely on reconnaissance and espionage efforts and did not systematically exploit other sources of information and produce finished intelligence summaries. This situation changed radically once Hooker took over.

Hooker understood the need for effective intelligence gathering and interpretation as well as good operational security practices to defeat enemy intelligence activities. Less than two weeks after he took command of the Army of the Potomac on January 26, 1863, Hooker issued a general directive to Provost Marshal Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick to “organize and perfect a system for collecting information as speedily as possible.” In response to Hooker’s wish, on February 11 Patrick named Sharpe deputy provost marshal general for the Army of the Potomac. Sharpe was tasked with establishing a secret service department. His appointment would turn out to be an excellent choice.

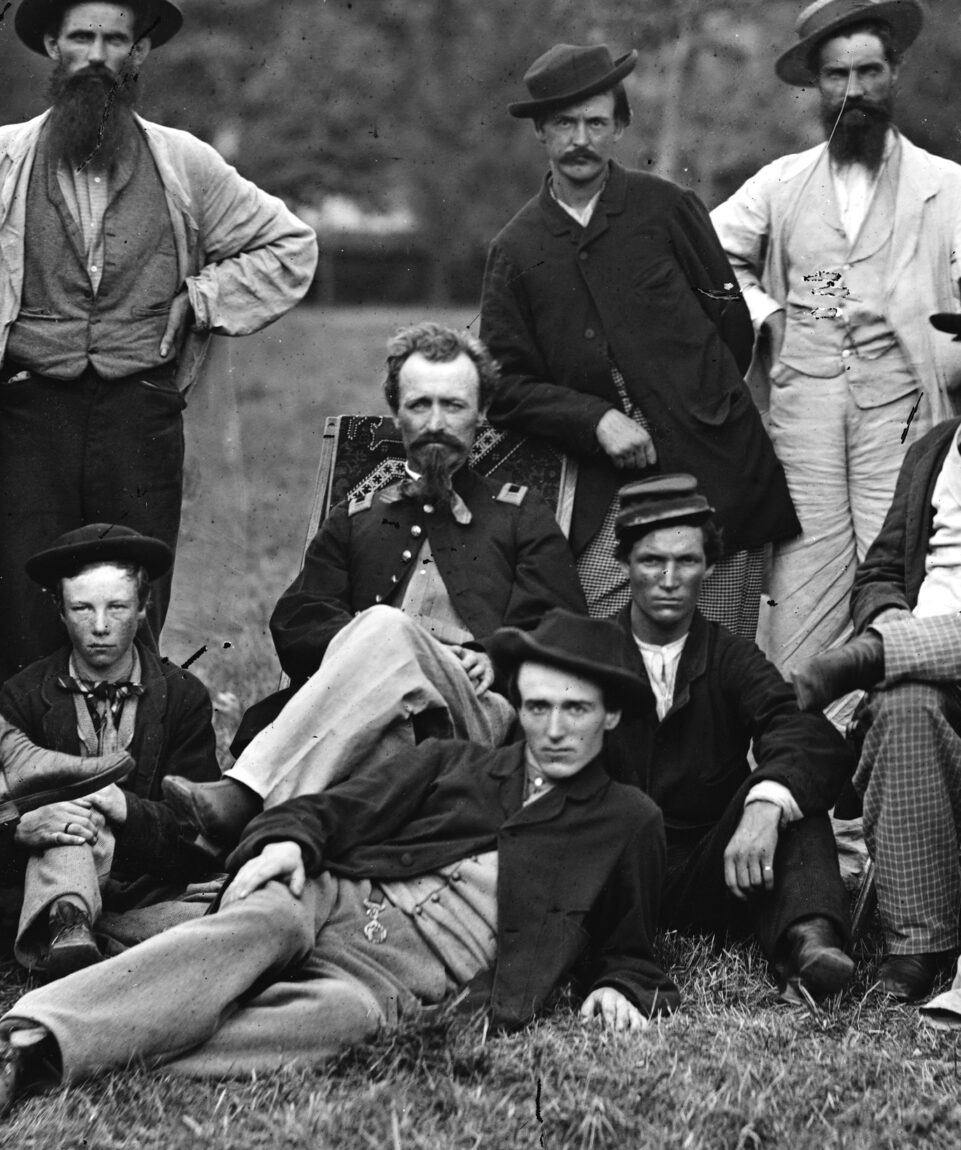

Sharpe was born on February 26, 1828, in Kingston, New York, to Henry and Helen Sharpe. He entered Rutgers University at age 15. In 1847 he graduated with honors from that institution. He subsequently graduated from Yale University Law School in 1849 at the age of 21. Afterward, he landed a job as an attaché to the U.S. embassy in Vienna.

In the early 1850s Sharpe became a highly successful attorney and investor in upstate New York. In 1858 he joined the 20th New York State Militia Regiment, being elected captain of Company B. After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, Sharpe and the 20th New York Militia were ordered to Maryland where they guarded railroads.

After the 20th Militia was released from service, Sharpe helped raise the 120th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. As its colonel, Sharpe and the 120th joined the Army of the Potomac at the start of the Fredericksburg Campaign. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, the 120th New York was held in reserve. After Fredericksburg, Sharpe attempted to have his command assigned to the Army of the Potomac’s Provost Marshal Guard. That assignment did not take place, but the request did bring Sharpe to the notice of U.S. Army Provost Marshal Marsena Patrick.

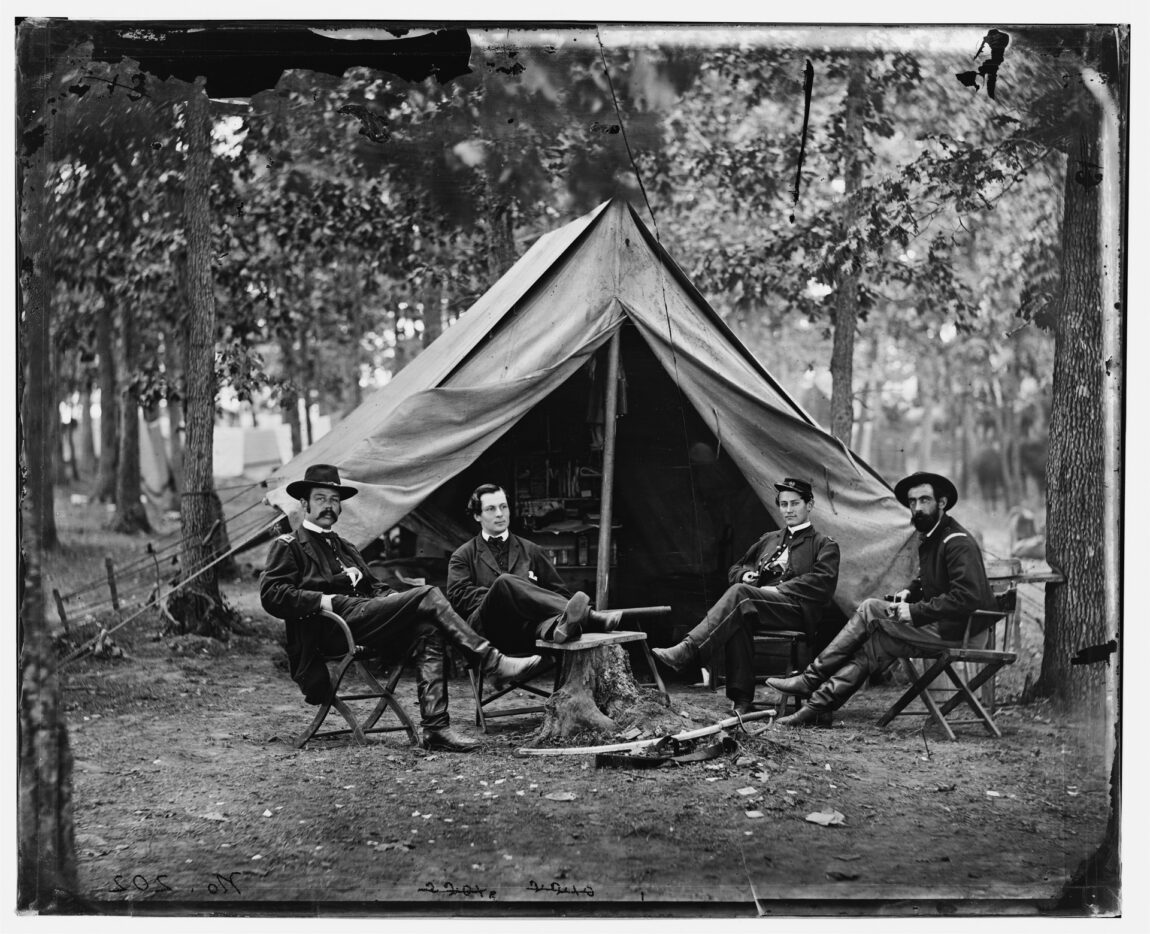

As the new spymaster for the Army of the Potomac, Sharpe brought his native intelligence, analytical thinking, strong work ethic, organizational skills, and charismatic personality to his new job. Sharpe and his intelligence staff generated intelligence using all available information sources, including scouts and spies, cavalry reconnaissance, Signal Corps observation and message interception, and aerial scouting from balloons. In addition, they culled Southern newspaper accounts and reports from other Union military commands. They also derived information from interrogation of prisoners, deserters, escaped slaves, and Union sympathizers. They analyzed the data and used it to create a picture of the enemy’s order of battle, strength, dispositions, movements, and morale. Afterward, Sharpe and his staff issued reports directly to the army commander.

Sharpe’s unit included two men whom he respected and relied on: John C. Babcock and John McEntee. The 26-year-old Babcock, a pre-war architect, had been an enlisted man in the U.S. Army when he worked for Allen Pinkerton. Soon after Burnside took charge of the Army of the Potomac, Babcock was mustered out of the service but, as a civilian, remained as Burnside’s chief of intelligence. Sharpe assigned him as the principal interrogator and leading analyst, as well as his second in command.

Before the war, McEntee was a flour and feed merchant near Kingston, New York, who had conducted business with Sharpe. McEntee had risen to the rank of captain for his meritorious service during the battles in the eastern theater in 1862. The 27-year-old officer was chosen by Sharpe to be a major player on the intelligence staff by leading its scout and spy teams in the field as well as serving as an interrogator and writing intelligence reports.

Previously known as the Secret Service Department, Sharpe changed the agency’s name to the Bureau of Military Information when he took over. The bureau initially was staffed by 20 employees. Although its staff increased, it never numbered more than 70 employees during the war. Sharpe picked soldiers from other commands in the U.S. Army with a wide variety of skills that would benefit his organization. Those recruited included scouts, detectives, telegraph operators, messengers, guides, and agents. He also sought out the services of local spies.

Hooker’s bureau was barely up and running when its mettle was tested by a major movement of the enemy. As a result of the Union IX Corps’ transfer from the Army of the Potomac to the Virginia Peninsula during the second week of February 1863, Lee dispatched his First Corps under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet from the main army to Suffolk, Virginia, as a counter to the Federal transfer. To verify Longstreet’s move south, Sharpe sent several of his scouts across the Rappahannock River, which was the boundary between the opposing armies, to investigate.

One of these, 38-year-old Sergeant Milton W. Cline of the 3rd Indiana Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, obtained the best results. Passing himself off as a Confederate scout, Cline managed to travel, with a Rebel mounted detail, the length and breadth of the Army of Northern Virginia’s positions, as well as well behind its front. The sergeant was not only able to report to his boss that part of Longstreet’s corps had in fact withdrawn from the Rappahannock and headed southeast, but also gave the locations of more than 125 Confederate military camps and other installations. Cline’s 250-mile sojourn between February 24 and March 5, 1863, was the deepest, most extended penetration of enemy lines by either side documented during the war.

On March 15, 1863, after only a month in existence, the bureau presented Hooker with an order of battle for the Army of Northern Virginia, as well as a record of its changing strength as it was gradually reinforced along the Rappahannock River. The report said Lee had 42,500 men when he actually had 49,000. Although the estimate was off, it was the most comprehensive piece of intelligence produced to date by the Army of the Potomac. The report prompted Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield, Hooker’s chief of staff, to write later that until the advent of the bureau “we were almost as ignorant of the enemy in our immediate front as if they had been in China.”

By mid-April 1863, Joe Hooker had decided to mount an offensive against Robert E. Lee by attacking the latter’s right flank and rear above Fredericksburg using his cavalry to get behind the enemy to cut his supply line to Richmond. The bureau, together with the army’s topographical engineers, mapped out the routes the army would take to accomplish its mission. About this time, Babcock submitted a revised Confederate order of battle as well as a new combat strength estimate. His report stated Lee had 52,200 men and 26 infantry brigades. Soon after the army started its march around the Confederate flank, Sharpe listed Southern strength at 54,600 and 243 cannons, which was relatively close to the actual numbers. Furthermore, Sharpe was able to inform Hooker that unlike the previous month, the Army of Northern Virginia’s western flank and rear was only thinly guarded. With this vital information in hand, Hooker revised his plan of attack: he would now use most of his infantry to slash behind Lee’s army and threaten his lifeline, thus forcing Lee to either run or fight at a disadvantage.

By day five (May 1) of Hooker’s offensive, the right wing of his army was a little to the east of Chancellorsville squarely on the Confederate left flank. An evening report from Sharpe indicated the only opposition facing the Union army was two Rebel infantry divisions. But a further report later that night stated that Lee had dispatched between 10,000 and 15,000 troops of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps to meet the Federals near Chancellorsville. After receiving this disturbing news of the enemy’s movement, Hooker elected to halt his own advance and concentrate for a defensive battle near Chancellorsville. By ceding the initiative to Lee, the Union army leader set in motion the events that would lead to his defeat during the campaign.

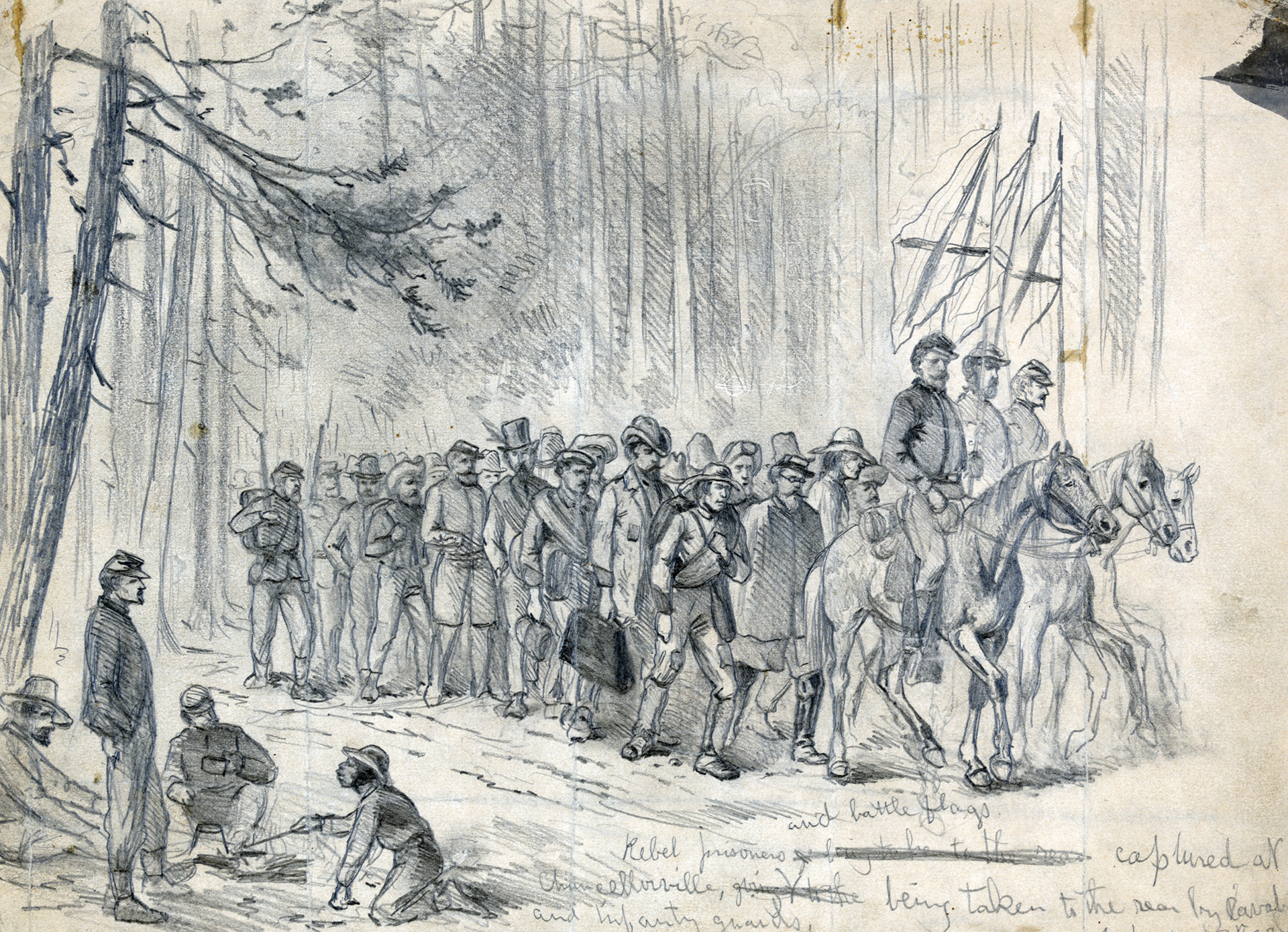

Sharpe’s last act would play in the ill-fated Union Chancellorsville Campaign was, as a member of the provost marshal’s staff, negotiating the exchange of 4,000 Federal wounded soldiers who had fallen into the hands of the victorious Confederates after the Army of the Potomac reclosed to the north side of the Rappahannock. In this endeavor he was successful and considered it one of his finest achievements during the war.

On June 3, 1863, Lee followed up his spectacular success at the Battle of Chancellorsville with an invasion of the North. Weeks before Sharpe, during a visit to Baltimore, had arranged for spies to discover just such a Rebel ploy. On May 27, Sharpe forwarded to army headquarters a summary of enemy intentions. After listing the number of brigades gathered under Lee, Sharpe ended his report by stating that Rebel deserters claimed that the Army of Northern Virginia was about to move north against the Army of the Potomac’s right flank.

To detect any enemy move north, at the end of May Sharpe sent a six-man detachment under McEntee to work with the Federal cavalry to scout the enemy, penetrate its lines, and gather as much intelligence as possible about Lee’s intentions. The results of McEntee’s and Sharpe’s efforts resulted in a report that Lee’s cavalry, under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, was about to embark on a big raid to the north from Culpepper Court House, Virginia. Sharpe’s analysis was incorrect, but it did set in motion the cavalry fight at Brandy Station, Virginia, on June 9. During this period Sharpe’s organization was staffed with only 18 men and thus was not robust enough to thoroughly and timely shift through all the voluminous and conflicting material coming to it. Further, the Union cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton, had been controlling the movements of Sharpe’s scouts and withholding information from Sharpe. As a result, the bureau’s effectiveness was at one of its lowest points during the war.

It was not until June 12 that information from some Negro slaves and observations by McEntee revealed that the Army of Northern Virginia was indeed heading north from the Rappahannock. Armed with this information, Hooker ordered his army in pursuit of the Confederates on June 14. Ten days later, Hooker received a report from Babcock conclusively stating that part of Lee’s army had crossed north of the Potomac River. The Federal commander, who up to that time was still not sure if Lee meant to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania, then ordered his own army to pass north of the Potomac. It was a critical decision that allowed the Union force to eventually catch up with its perennial adversary in Pennsylvania.

Crossing the Potomac immensely aided Sharpe’s quest for intelligence. Between June 24 and the first day’s battle at Gettysburg on July 1, he received more than 100 reports, 75 percent of which were accurate, from his people as well as scores of citizen scouts regarding the strength and movements of the Southern army. Sharpe compiled almost all the analytical summaries based on this mass of material, and they were used to good effect by the new head of the Army of the Potomac.

On May 28, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac. He immediately used the information collected by the bureau to fan his army out in the Pennsylvania countryside in order to keep it reasonably concentrated and at the same time counter any moves on the part of his opponent. By June 30 Meade had enough intelligence from Sharpe to order a concentration in the vicinity of Gettysburg, where a major battle was fought July 1-3. After battling for two consecutive days, Meade was concerned that his army could no longer continue the contest. His decision whether to stay and fight or withdraw in part hinged on the news from Sharpe that most of Lee’s army had been committed to the battle and that the enemy was as used up as Meade’s force was. Meade decided to remain in the fight, resulting in a clear Union victory by the end of July 3.

Operations of the opposing armies between late July 1863 and April 1864 involved only a few major maneuvers and only one major clash, the Battle of Bristoe Station fought October 14, 1863. These events did not give the bureau much scope for action. This would change in May 1864 when the Army of the Potomac embarked on the Overland Campaign accompanied by General of the Army Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Before the 1864 spring campaign season opened, Sharpe had placed intelligence liaison officers with the Army of the James and the Federal army in the Shenandoah Valley. During the first month of marching and fighting Sharpe used his scouts, in conjunction with Signal Corps parties, to accumulate intelligence to guide the efforts of the Army of the Potomac. Sharpe spent much of his time meeting with Grant and coordinating bureau operations with Grant’s staff. In early July, the bureau was renamed, by order of Grant, as the Bureau of Information. This reflected the fact that Sharpe was not only back in the business of all-source intelligence, but no longer under Meade’s control. Sharpe now reported directly to Grant. It also started a system of close intelligence coordination, supervised by Sharpe, between the Union armies before Richmond and the Shenandoah Valley army under Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan.

In July Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early took the Army of Northern Virginia’s II Corps on a raid into the North, threatening the safety of Washington, D.C. Panic gripped the Lincoln administration upon Early’s approach to the capital. Sharpe was sent to calm the fearful politicians who swore Early had close to 100,000 men. Sharpe reassured them the Southerner had no more than 25,000 soldiers (he had only 13,000 troops), and he “offered a heavy bet that they [the Confederates] would fall back the moment the VI Corps [from the Army of the Potomac] appeared in front of Washington.” And that turned out to be the case.

As the siege of Petersburg and Richmond by the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James, which had commenced in June, dragged on, Sharpe strengthened his connection with the pro-Unionist underground in those towns, the most prominent being the group led by spinster Elizabeth Van Lew of Petersburg. Sharpe encouraged these clandestine organizations to report on Southern troop movements, troop morale, and the state of Rebel fortifications in and around Richmond and Petersburg.

In February 1865 Sharpe was promoted to brigadier general. One of the last acts of his military career was to supervise the parole of members of the Army of Virginia after their surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Returning to Kingston in June 1865, Sharpe resumed his law practice. Two years later he was sent to Europe by the Johnson administration to track down John Surratt, a suspected Lincoln assassination conspirator. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Sharpe to serve as U.S. Marshal for the Southern District of New York in 1869 and surveyor of New York customs until 1878. Later Sharpe combined the practice of law with participation in local politics until his death in January 1900.

The Bureau of Military Information was successful because it effectively collated and analyzed masses of information from a variety of sources, presenting the finished product in a concise daily written summary. These provided not raw information but a careful analysis. This practice marked the first time in American military history that a professional department collected and analyzed information for the commanding general to aid him in the strategic and tactical decision-making process. The process was not fully replicated until World War II. What was equally significant was that none of its members was an intelligence professional.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments