One of the enduring questions surrounding post-World War II Tokyo war crimes trials has apparently, at long last, been answered.

In the early morning hours of December 23, 1948, former Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and six other convicted “Class A” war criminals were executed by hanging at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. The bodies were cremated, but from there the story of the disposition of the ashes has been buried in the recesses of the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The circumstance has remained a mystery—particularly among the Japanese people—for more than 70 years.

Last spring, Hiraoki Takazawa, a professor at Tokyo’s Nihan University, revealed that he had located documents that provide a detailed description of the hours that followed the executions and cremation. At the National Archives, Takazawa located documents revealing that the ashes were scattered from a U.S. Army aircraft roughly 30 miles off the coast of Japan and east of Yokohama. The reason for the cremation and covert scattering was ostensibly to prevent Tojo loyalists and radical, diehard nationalists from using an interment location as some sort of shrine.

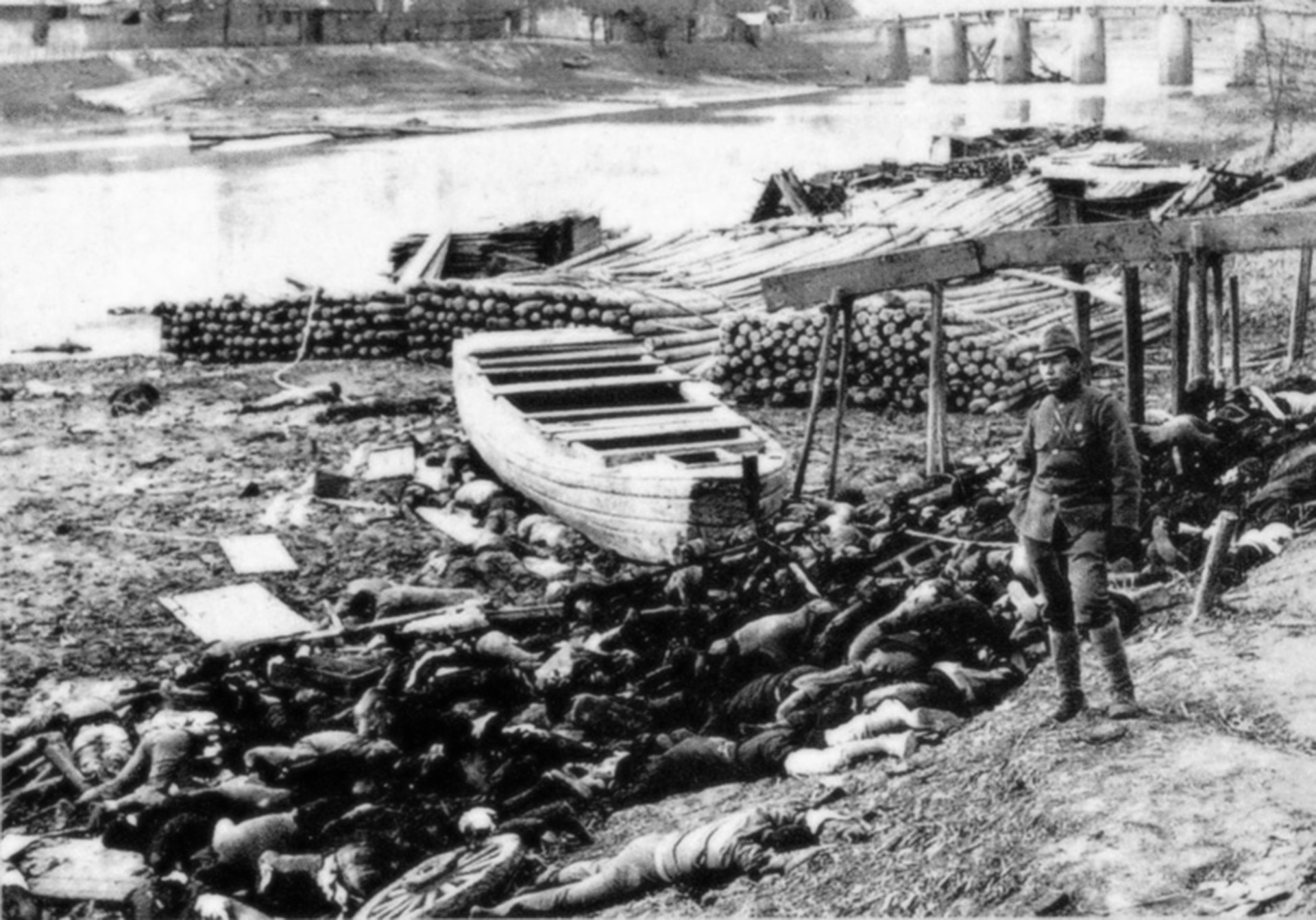

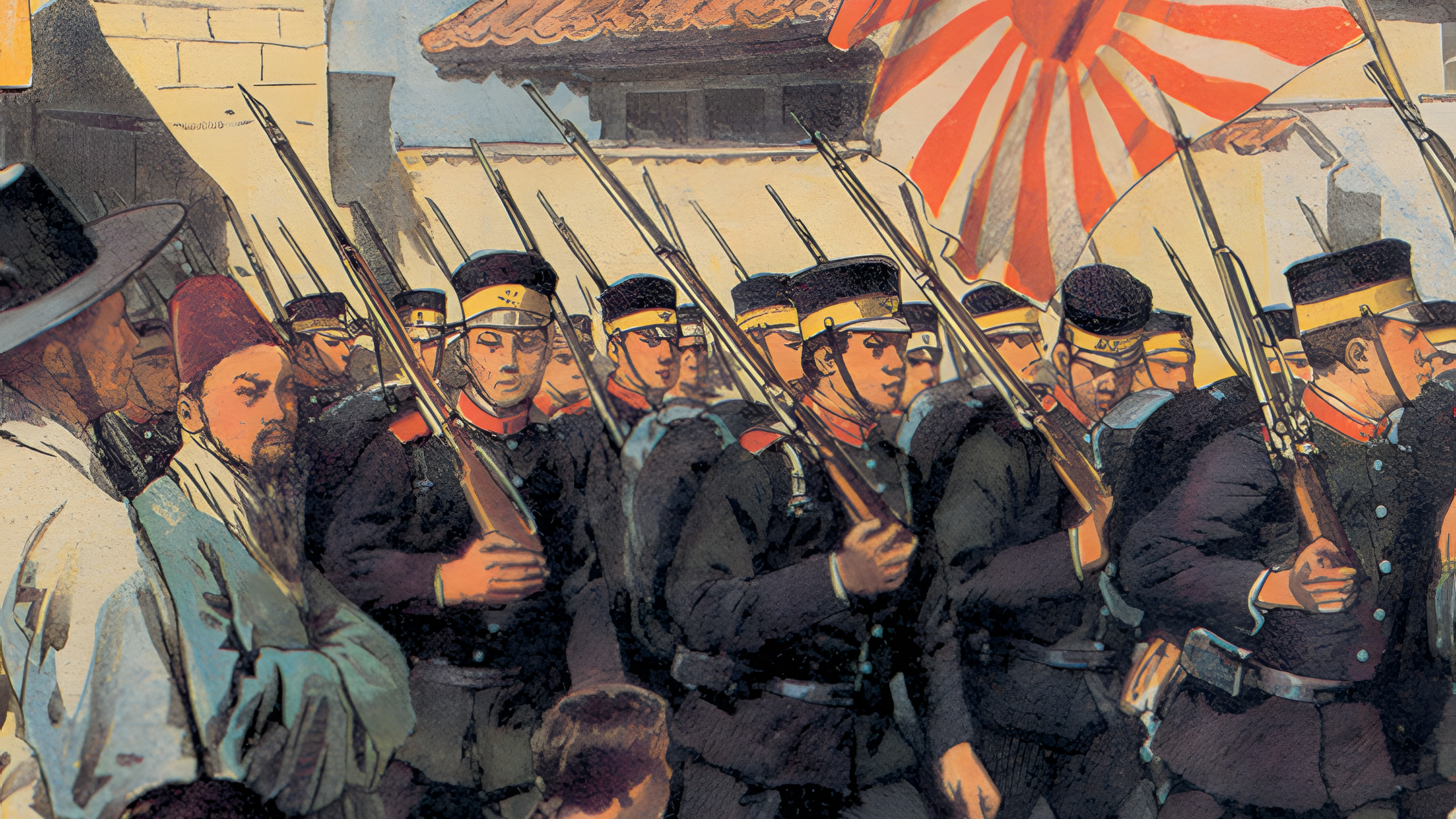

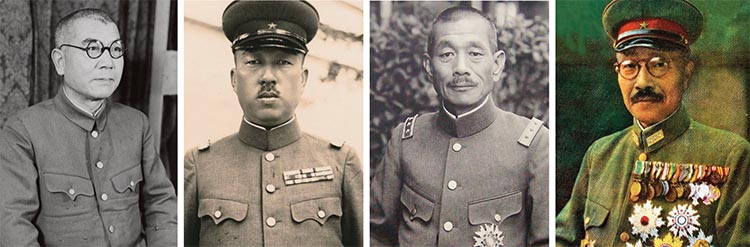

The six other war criminals included Kenji Doihara, Koki Hirota, Seishiro Itagaki, Heitaro Kimura, Iwane Matsui, and Akira Muto, each of them responsible as a high-ranking military officer or civilian official for the notorious “Rape of Nanking” during the Second Sino-Japanese War or for atrocities committed in other areas of Southeast Asia and the Philippines against civilian populations or prisoners of war.

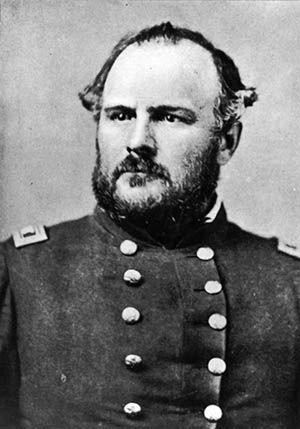

Among other documents Takazawa located a memorandum stamped “secret” that had been authored by U.S. Army Major Luther Frierson. It reads in part: “I certify that I received the remains, supervised cremation, and personally scattered the ashes of the following executed war criminals at sea from an Eighth Army liaison plane …” Frierson wrote a more detailed account in early 1949, further noting, “We proceeded to a point approximately 30 miles (48 kilometers) over the Pacific Ocean east of Yokohama where I personally scattered the cremated remains over a wide area in accordance with letter GHQ, 13 August 1948.”

The major certified that the corpses were fingerprinted for identification purposes, placed in caskets, and then loaded onto a 2 ½-ton truck at Sugamo. A heavily guarded motorcade left the prison minutes later, arriving at a U.S. Army military graves-registration platoon facility in Yokohama just after 1:30 am.

The bodies arrived at the crematorium at 7:25 am and were quickly placed into cremation ovens. The entire facility was heavily guarded. The ashes were deposited into separate urns, and extreme care was taken to remove the residue in its entirety. However, some ashes belonging to at least one of the condemned may have been surreptitiously scooped up and saved for the family.

Although there were reportedly no ashes to place at the sacred Shinto Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where 2.5 million Japanese war dead are revered as sacred spirits, the seven executed war criminals were nevertheless honored with enshrinement in 1978. Since then, the Yasukuni Shrine has been a source of controversy, particularly regarding Japanese relations with China and South Korea, whose peoples suffered mightily at the hands of Japanese aggression.

When the Associated Press contacted Prime Minister Tojo’s great grandson, Hidetoshi Tojo, the descendant remarked that he was pleased with the recent news. “If his remains were at least scattered in Japanese territorial waters … I think he was still somewhat fortunate. I want to invite my friends to lay flowers to pay tribute to him….”

Takazawa speculated, “The entire operation was tense, with U.S. officials extremely careful about not leaving a single speck of ashes behind, apparently to prevent them from being stolen by admiring ultra-nationalists. I think the U.S. military was adamant about not letting the remains return to Japanese territory … as an ultimate humiliation.”

Regardless of the U.S. and Allied intent, the international tribunal had rendered its verdict. The sentence had been carried out. Humiliation? Perhaps. Retribution? Certainly.

—Michael E. Haskew