By Christopher Miskimon

Victory in Europe during World War II is often attributed to various exertions, turning points, and campaigns that spanned several theaters of war. All played their part in achieving final victory, and opinions vary as to how important most of these events were in the grand scheme. A few are undisputedly vital links in the Allied victory over Nazi Germany. The years-long struggle in the frigid waters of the Atlantic Ocean is one of those supremely substantial efforts from which ultimate triumph flowed. Without control of the sealanes between the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, Germany could not have been defeated as quickly and finally as it was.

A new coffee table book gives the history of this war at sea. Battle for the North Atlantic: The Strategic Naval Campaign That Won the War in Europe (John R. Bruning, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2013, 300 pp., maps, photographs, index, $40.00, hardcover) is far from the first book to cover this topic, but is a thoroughly enjoyable work that highlights the major events of the Battle of the Atlantic while also covering details of daily life at sea and the constant efforts by each side to attain dominance over the other.

A new coffee table book gives the history of this war at sea. Battle for the North Atlantic: The Strategic Naval Campaign That Won the War in Europe (John R. Bruning, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2013, 300 pp., maps, photographs, index, $40.00, hardcover) is far from the first book to cover this topic, but is a thoroughly enjoyable work that highlights the major events of the Battle of the Atlantic while also covering details of daily life at sea and the constant efforts by each side to attain dominance over the other.

The text of the book is well researched and diverse, covering the numerous aspects of the campaign. The author explains how prewar budgets and shipbuilding programs defined the fleets at the war’s beginning and how wartime planning and construction had to make up for a lack of Allied foresight in terms of convoy escorts and antisubmarine capability. Intelligence efforts played a large part in the eventual Allied success as British codebreakers deciphered German message traffic and had to play the knife’s-edge game of using the information without revealing its source.

Though there were a few exchanges between capital ships in the Atlantic, the majority of the war was fought by submarines, merchantmen, escorts, and aircraft carriers. Improved sonar and antisubmarine weapons such as the hedgehog spigot mortar fitted to the escorts vastly increased their effectiveness against U-boats. Meanwhile, the Germans steadily improved their own submarines to combat Allied countermeasures. It was a struggle the Germans eventually lost, but not until U-boat crews nearly brought Britain to its knees. Casualties were high on both sides, and the U-boat crews suffered about 75 percent casualties over the course of the war.

While ship versus ship battles and fights against the submarine threat were no doubt important, really the war-winning weapon in the Battle of the Atlantic was the aircraft. Even the Germans had some success with Luftwaffe antishipping strikes early in the war. Planes such as the Focke Wulf Fw-200 Condor were used briefly to great effect until the British got enough fighters in the air to counter them. Afterward, the air war over the ocean was an Allied effort. Long-range patrol planes eventually squeezed the air gap in the mid-Atlantic tighter until the appearance of sufficient numbers of escort carriers closed it for good. The airplane’s ability to search large areas of ocean and then quickly bring firepower to bear on a U-boat combined with the explosion in escort ship production to make successful U-boat patrols an increasing rarity from mid-1943 on.

While this book’s text is good, its illustrations and photographs shine. The layout is well designed and the photos themselves well chosen. Using pictures from both sides of the conflict and mating them to the text, the reader can view the major personalities, see ships and planes in action, and appreciate sad images of sinking merchant vessels, the smoking twisted wreckage of warships, and the outlines of the various aircraft that fought in the skies over the Atlantic. Maps are included where relevant, and the overall aesthetic of the book is pleasing to the eye and makes one want to turn each page.

Intrepid Aviators: The American Flyers Who Sank Japan’s Greatest Battleship (Gregory G. Fletcher, NAL Caliber, New York, 2013, 420 pp., maps, photographs, notes, appendices, index, $16.00, softcover).

Intrepid Aviators: The American Flyers Who Sank Japan’s Greatest Battleship (Gregory G. Fletcher, NAL Caliber, New York, 2013, 420 pp., maps, photographs, notes, appendices, index, $16.00, softcover).

Naval aviation is a world unto itself, requiring unique sets of skills and knowledge. During World War II carrier pilots were often men as young as 20 with a sprinkling of older pilots often in leadership positions. This brought challenges to making an aircraft carrier’s air group an effective weapon. Forming and training the group was a long, arduous process. New pilots had to learn how to navigate over open ocean, take off and land on a moving, rolling flight deck, and coordinate fighter, dive bomber, and torpedo attacks. This book tells the story of Air Group 18 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid.

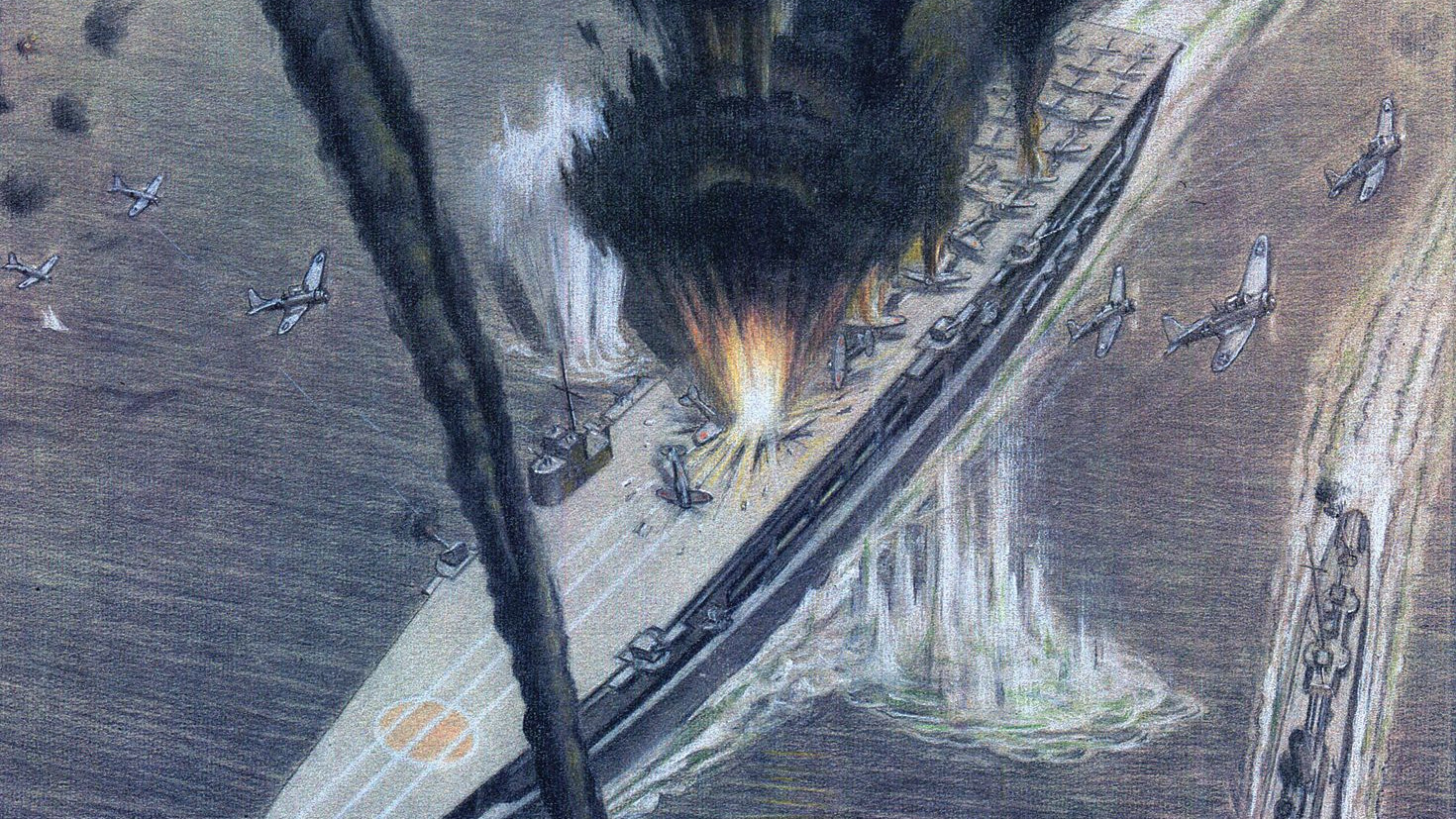

Wartime air groups underwent extensive training long before they went aboard a carrier. Once aboard Intrepid, Air Group 18 continued training even as the ship cruised into Pacific waters. The first combat missions were relatively easy, designed to blood the new pilots. As time went on the missions became more difficult; the pilots gained experience even as they began to take losses. The height of Group 18’s war was the attack on the Japanese super battleship Musashi in the Sibuyan Sea on October 24, 1944. Repeated strikes against the ship by multiple aircraft sent the leviathan to the bottom after at least 15 bomb and 10 torpedo hits.

While covering the entire air group in general, the focus of the book is on VT-18, Intrepid’s torpedo bomber squadron. In its first strike against Musashi, two of the squadron’s Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers were shot down. Of the six airmen, only a single pilot survived. He had to dodge a Japanese destroyer and swim miles to a nearby island, his survival plagued by hunger and dehydration. Eventually, he joined a group of Filipino guerrillas and fought the Japanese until liberation months later. Torpedo bombers were the most vulnerable of an air group’s planes due to their heavy payloads and the relatively low and approach required for a successful torpedo attack.

For readers interested in naval aviation or the Pacific War, this well-researched book is a trove of detailed information. The author extensively describes the actions needed for takeoffs, landings, attack runs, and air combat in minute detail. A carrier pilot himself, the author brings that experience to the book in relating a pilot’s life aboard ship and in the air. These small details are used to weave a coherent and flowing narrative for Air Group 18 throughout the war.

Stalin’s Claws: From the Purges to the Winter War (E.R. Hooten, Tattered Flag Press, West Sussex, UK, 2013, photographs, notes, appendices, index, $39.95, hardcover).

Stalin’s Claws: From the Purges to the Winter War (E.R. Hooten, Tattered Flag Press, West Sussex, UK, 2013, photographs, notes, appendices, index, $39.95, hardcover).

The actions of the Red Army prior to Operation Barbarossa are usually summed up in its Winter War against Finland in 1940-1941. However fascinating that conflict remains, it is just part of the story. From the beginning of the purges to the German invasion, the Soviet Union used its army in many operations along its borders. Stalin’s Claws explains these numerous actions along with the political processes behind them in detail.

The author begins with an overview of the purges. This veritable assault upon the Soviet officer corps decimated its ranks and instilled a survival mentality in most of those left. This witch hunt against perceived enemies of the state went to depths of paranoia that boggle the mind even today. Some who sat in judgment knew they would be next. Many were shot, others imprisoned, with only a handful being reinstated after the June 1941 invasion by the Nazis.

The Soviet Union found itself embroiled in combat while the purges continued in 1938-1939. A series of border conflicts with Japan ended in victory at the Battle of Khalkin Gol. When Stalin agreed to a nonaggression pact with Hitler, it spelled out the partition and doom of Poland. Yet the Soviet attack and occupation of that nation was only one step. The Baltic States were next, forced to concede to occupation. Later Bessarabia and Bukovina would follow.

By far the largest of these conflicts was the Winter War with Finland, and it is well documented here. The Red Army was initially stymied by the smaller Finnish military, given a bloody nose and a rude awakening. The effects of the purges were still evident. As they would later do against the Nazis, however, the Soviets rallied their vast resources and pushed on to a victory over the Finns, which had repercussions later in World War II. Finally, the Soviet Union was triumphant for a short period until Operation Barbarossa.

This book is long on detail, and complete orders of battle for each operation are in the appendices. The details of each action tend to be broad brush strokes, but this is typical of works covering the vast scopes of the Red Army’s activities. Readers interested in the Soviet Union and Red Army will find this work of interest.

Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II (Judith Barger, Kent State University Press, Kent, 2013, 285 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $28.95, hardcover).

Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II (Judith Barger, Kent State University Press, Kent, 2013, 285 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $28.95, hardcover).

During World War II, over one million American casualties were evacuated via aircraft. For some theaters of war it was a necessity; the jungles of New Guinea and Burma or the frozen wastes of Alaska made ground evacuation difficult to impossible. Even in the relatively built up terrain of Europe, aerial evacuation was used to take wounded soldiers back to the United States for treatment. On those flights was a new and relatively unknown boon to the injured and sick, a U.S. Army flight nurse.

Before the war, commercial airlines hired only registered nurses to be flight attendants. One U.S. officer put it plainly, stating, “We felt that if … a group of healthy individuals could fly around in commercial airlines having a nurse attend them, our wounded were certainly entitled to the same consideration.”

Readers interested in the story of these flight nurses can now learn their tale. The first such nurses began their story in the 1930s through the budding aviation industry and affiliation with the Red Cross. Once the war began, these nurses lobbied to be allowed to use their skills in the Army Air Corps. At first, however, the military told them they could guarantee flight status to any who volunteered, though previous experience would be taken into consideration. Eventually, a school for flight nursing was established to train the volunteers to a uniform standard.

After training, the newly minted flight nurses were sent to do their jobs but still had to fight through some institutional roadblocks. For example, the initial nurse’s uniform included a skirt and heels, not very practical in an aircraft where the nurses had to wear parachutes with straps that went between the legs for fastening. A practical demonstration, complete with stalled engines, was needed to prove the point and get the women pants. The first nurses to serve in a combat theater went to North Africa. From there they went on to serve in every theater, caring for patients and saving lives. Their hard work and success paved the way for postwar flight nurse programs that continue to this day as a proven asset of the military medical services.

This book is easy to read and is clearly written from a hand of experience (the author was a career USAF nurse). While the general story of the flight nurses is covered in detail, space is set aside for some of the unusual tales, such as nurses who were prisoners of war or were downed behind enemy lines and how they met the particular challenges of their situation. One chapter covers how flight nurses were viewed in the contemporary media and by their fellow service members.

Wavell in the Middle East, 1939-1941: A Study in Generalship (Harold E. Raugh, Jr. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013, 323 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $24.95, paperbound).

Wavell in the Middle East, 1939-1941: A Study in Generalship (Harold E. Raugh, Jr. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013, 323 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $24.95, paperbound).

When the subject of British World War II generals arises, most Americans think of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery first, with perhaps a few thoughts going to William Slim, Claude Auchinleck, or Harold “Jumbo” Wilson. A man they should think of is Field Marshal Archibald Wavell. While circumstances denied him the fame gained by others, Wavell held the line during some of the darkest days of the British Empire in the early years of World War II. A textbook example of the “quiet professional,” he led Commonwealth forces through a series of campaigns in the Middle East, many of them simultaneously, with forces that were often outnumbered and ill equipped for the tasks assigned them. Nevertheless, his troops were able to attain victory most of the time and protect the Empire’s vital oil-producing and transportation links.

This book studies Wavell during the time of his greatest challenge. In 1939, he was placed in command of British forces in the Middle East, an area ranging from the Western Desert of Egypt east to Iraq and the Persian Gulf and south to the Sudan and Aden. After the war began, this area was expanded to include Greece and Turkey, as well as Libya, parts of Algeria, and portions of Africa as far south as Rhodesia. The Italians and later Germans were active in North Africa, Ethiopia, and Syria, even working in Iraq to support an uprising there in the spring of 1941.

Wavell’s forces had to contend with all this despite shortages of troops and equipment. Britain, reeling under the Blitz and threatened by invasion, could send only limited aid. For example, Italian troop strength in Libya was over 150,000 versus some 36,000 British when Mussolini’s forces invaded Egypt in the autumn of 1940. Despite this, Wavell’s Operation Compass knocked the Italians out of Egypt and halfway across Libya, inflicting a loss of over 100,000 prisoners. His shoestring operations were strained further by the requirement to support operations in Greece, fight in East Africa, and suppress the Iraqi uprising.

The invasion of Vichy French-held Syria and the defense of Crete after the defeat in Greece were further stresses. Through all this Wavell and his soldiers were on occasion able to achieve outright victory or at least stave off defeat. Unfortunately, holding the line against long odds was not the same as victory, and Churchill eventually replaced Wavell with a series of successors who found the job every bit as difficult despite Wavell having taken Syria and East Africa and suppressed rebellion in Iraq.

This work is well done with each separate campaign compartmented into its own chapter for ease of understanding. Good maps accompany the text. The book as a whole takes a chaotic and fast-moving period and makes it accessible for the student of the Middle East in World War II.

Our Tortured Souls: The 29th Infantry Division in the Rhineland, November-December 1944 (Joseph Balkoski, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 386 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover)

Our Tortured Souls: The 29th Infantry Division in the Rhineland, November-December 1944 (Joseph Balkoski, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 386 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover)

Stackpole Books is known for its detailed accounts of the European Theater in World War II, whether on land or in the air and from both sides of the fighting. This book relates one of the toughest periods for the U.S. Army’s 29th Infantry Division, during the Allied attempt to reach the Rhine by Christmas 1944 and hopefully end the war.

The 29th Division was a National Guard unit made up primarily of outfits from Maryland and Virginia. It fought its way ashore at Omaha Beach on D-Day and had been in near continuous combat since. It had taken nearly 100 percent casualties in its infantry regiments, meaning all three units had replaced their contingents from June to November 1944. Despite this, the division was assigned to take part in a new offensive beginning November 16.

Designed to open the heart of Germany and the Rhine region to Allied assault, it required the 29th to advance 10 miles, cross the Roer River, and take the city of Julich, Germany. Three weeks later, the advance ground to a halt on the west side of the Roer. The division had suffered 2,600 casualties but was unable to seize all its objectives due to stiffening German resistance and bad weather.

The book is full of detail and covers the actions of generals and privates alike. The author is known for his detailed accounts and does not disappoint here. The book is obviously the result of extensive interviews and meticulous research. For those interested in the European Theater, it is a valuable story of the 29th Division between the hedgerows of Normandy and the frigid hell of the Bulge.

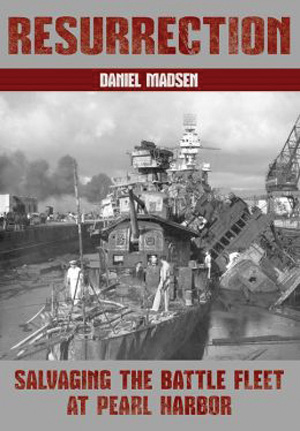

Resurrection: Salvaging the Battle Fleet at Pearl Harbor (Daniel Madsen, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 241 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, softcover).

Resurrection: Salvaging the Battle Fleet at Pearl Harbor (Daniel Madsen, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 241 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, softcover).

One of the lesser heralded engineering miracles of World War II was the recovery of the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s ships sunk at Pearl Harbor. It is well known that many of the battleships lost on December 7, 1941, were later raised, refitted, and returned to duty, generally as fire support ships for amphibious invasions. Exactly how this happened has been only briefly touched upon until now. This book corrects that deficiency.

The story begins in the immediate aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack. The harbor was slick with oil, and bodies were still being pulled from the water and from the capsized hull of the battleship USS Oklahoma. The fleet had been dealt a serious blow, but within days the Navy began to recover. A salvage organization was created to refloat ships that could be rebuilt and strip anything useful from those that could not. The shattered battleship Arizona was almost immediately written off; the partially sunk battleships California and West Virginia and other ships were salvageable. Getting them off the muddy bottom of the harbor would be no small task, however.

A horde of divers, engineers, and sailors came together to perform one of the unsung engineering miracles of the war. Badly damaged ships were patched, drained, refloated, and send to drydock. They had to be cleaned of oil, saltwater, rotten food, and the decomposed bodies of the fallen. Ships with multiple bomb and torpedo holes were made ready to fight again.

This work is fascinating and detailed, though it is technical in nature and a technical understanding of warships will help the reader. It is well researched and contains many small details of the salvage process and the difficulties involved in carrying it out during wartime, when resources were stretched thin. Many photographs from the period help explain the ingenuity and hard work involved in the process.

The attack on Pearl Harbor has been well documented elsewhere; this book rounds out the aftermath of the first battle of the Pacific War, where lost ships were actually brought to life again.

New and Noteworthy

Rendezvous with Destiny: How Franklin D. Roosevelt and Five Extraordinary Men Took America into the War and into the World (Michael Fullilove, Penguin, 2013, 480 pp., $29.95, hardcover). Five men worked for and influenced President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the critical years 1939-1941; “Wild” Bill Donovan, Sumner Welles, Harry Hopkins, Wendell Wilkie and Averell Harriman. Their work was critical to his effort to carry America through the war.

Rendezvous with Destiny: How Franklin D. Roosevelt and Five Extraordinary Men Took America into the War and into the World (Michael Fullilove, Penguin, 2013, 480 pp., $29.95, hardcover). Five men worked for and influenced President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the critical years 1939-1941; “Wild” Bill Donovan, Sumner Welles, Harry Hopkins, Wendell Wilkie and Averell Harriman. Their work was critical to his effort to carry America through the war.

The Love-charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (Lara Feigel, Bloomsbury Press, 2013, 519 pp., $35.00, hardcover). This book records glimpses of the London Blitz from the view of five prominent literary authors of the time. Some worked as volunteers for the war effort, but all kept diaries and wrote extensive correspondence. These writings are woven together into a tale of the times.

Cronkite’s War: His World War II Letters Home (Walter Cronkite IV and Maurice Isserman, National Geographic, 2013, 318 pp., $28.00, hardcover). This is a compilation of the famous journalist’s letters, written to various associates, with text added to fill in the story of Cronkite’s wartime experience.

Roosevelt’s Centurions: FDR and the Commanders He Led to Victory in World War II (Joseph E. Persico, Random House, 2013, 650 pp., $35.00, hardcover). During World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt rode herd on a number of military leaders, guiding them toward ultimate victory. Major figures from George C. Marshall to Joseph Stilwell figure prominently in the story of how FDR led this group and the nation to victory.

Tomorrow You Die: The Astonishing Survival Story of a Second World War Prisoner of the Japanese (Andy Coogan, Mainstream Publishing, 2013, 255 pp., $16.95, softcover). Captured at the fall of Singapore, Andy Coogan spent three years as a prisoner of the Japanese. His journey took him through Taiwan and Japan to Nagasaki.

Tomorrow You Die: The Astonishing Survival Story of a Second World War Prisoner of the Japanese (Andy Coogan, Mainstream Publishing, 2013, 255 pp., $16.95, softcover). Captured at the fall of Singapore, Andy Coogan spent three years as a prisoner of the Japanese. His journey took him through Taiwan and Japan to Nagasaki.

Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II (Arthur Herman, Random House, 2013, 413 pp., $18.00, softcover). Two businessmen, William Knudsen and Henry J. Kaiser, were instrumental in mobilizing the U.S. industrial base for war production. Their efforts turned the nation into the arsenal of democracy.

Battle Colors, Volume V (Robert A. Watkins, Schiffer Publishing, 2013, 152 pp., $45.00, hardcover). Part of Schiffer’s series on the insignia and markings used by the U.S. Army Air Corps, this volume focuses on the Pacific Theater. It has Schiffer’s usual thoroughness and attention to detail.

Images of War Special: Tiger I and Tiger II (Anthony Tucker-Jones, Pen and Sword, 2013, 176 pp., $24.95, softcover). This is a photo book concentrating on Germany’s Tiger tank series. The author compares the myths that have grown around them to the reality of their service.

Mussolini’s Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina, 1930-1945 (Maurizio Brescia, Naval Institute Press, 2012, 256 pp., $72.95, hardcover). This is a guidebook to the Italian Navy of World War II. This reference work covers the topic in greater detail than any other English language work available.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments