By Roy Morris Jr.

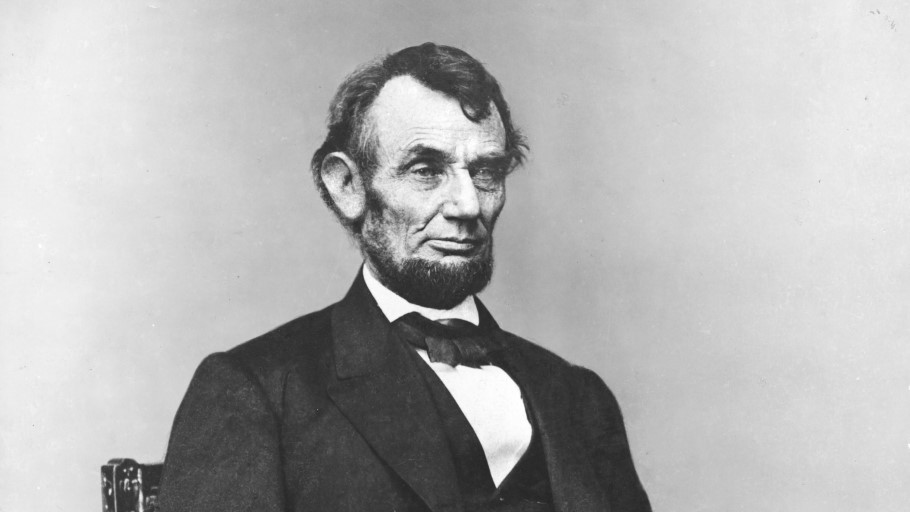

When Abraham Lincoln signed into law the first conscription act in American history in March 1863, one of the most unpopular parts of the widely unpopular act was the provision allowing draft-eligible males to hire substitutes to take their place in the army. Since few poor men could afford the going rate of several hundred dollars per substitute, the provision was seen as yet another sign that the war was “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

To combat that perception and set a good example for the nation, Lincoln, although long past draft age himself at age 55, decided in the summer of 1864 to hire his own substitute. (Some cynics noted that the presidential election was just around the corner and suggested that Lincoln was simply making a gesture to curry favor with voters, many of whose own sons were away serving in the Union Army at the time.)

In fact, the president was responding to a call by Provost Marshal James Fry for all men legally exempted from the conscription act and the draft to hire substitutes anyway to show support for the Union cause. Lincoln instructed Fry to find “as nearly a perfect man physically and morally” as he could to represent the president. Fry, in turn, asked Noble Larner, president of the Third Ward Draft Club, to locate a suitable substitute for Lincoln. (Draft clubs raised money to pay substitutes to bypass unscrupulous bounty brokers.)

Larner found a willing volunteer in 20-year-old John Summerfield Staples, of Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, the son of a Methodist minister. As reported by the Washington Star, “Staples is not so tall as the President, but is well formed, stout and healthy, and there is every indication that he will prove an excellent soldier.” Staples, in fact, was quite short—only 5 feet, 6 inches tall. His company sergeant, on hearing that the new recruit was Lincoln’s personal substitute, took one look at the stocky Staples and joked, “Aren’t you just the first installment?”

Lincoln met with Staples, Fry, and Larner at the White House. He shook hands with the young man, asked if had been properly mustered in—he had—and remarked, according to the New York Herald, “that he was good-looking, stout and healthy-appearing man, and believed he would do his duty.” Larner presented the commander-in-chief with a framed notice that he had provided the army with a suitable substitute, and Lincoln took his leave after expressing the hope that Staples would be “one of the fortunate ones” and survive the war.

Staples, in fact, had already survived a brush with the military two years earlier. On November 5, 1862, not yet 18 years of age, he had enlisted in Company C, 176th Pennsylvania Volunteers as a paid substitute for one Robert A. Barry. After seeing combat in North Carolina, Staples contracted typhoid fever and was honorably discharged on May 5, 1863, after a four-month stay in the hospital. He was working as a carpenter at the Washington Navy Yard when Larner happened to encounter him on Pennsylvania Avenue in late September 1864 and asked if he was willing to become a substitute for the president.

Staples duly enrolled in Company H, 2nd District of Columbia Volunteers; his father, Reverend John Long Staples, became regimental chaplain. The unit remained in Washington for the duration of the war, seeing no combat, and Staples served as a guard at Prince Street Prison across the Potomac River in Alexandria. Falling ill again with a recurrence of typhoid fever, he was allowed to return home to recuperate. In the interim, the war ended and he and his father were mustered out of the service in September 1865.

Following the war, Staples worked as a railroad car repair man in several northeastern cities before dying of a heart attack at his boarding house in Dover, N.J., on January 11, 1888. He was not yet 44 years old. He was buried at Stroudsburg Union Cemetery, where a bronze plaque notes, “Within this cemetery are the remains of John S. Staples who served as a substitute recruit for Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War.” (Read more about the lesser known events from the Civil War inside Military Heritage magazine.)

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments