By Glenn Barnett

In Hawaii, on Saturday, December 6, 1941, Commander Cassin Young eased his repair ship, Vestal, outboard of the battleship USS Arizona. Soon the two ships were moored together, bow to stern along Battleship Row because on Monday, Vestal was to begin preparing the Arizona to go into dry dock—an event that, infamously, never happened.

Commissioned as a collier in 1908, Vestal was one of the oldest ships in the U.S. Navy. She was converted to a repair ship in 1913 and still served in that capacity in 1941. Her commanding officer, Cassin Young, was born in 1894. He was a descendent of Steven Cassin, a naval hero of the War of 1812. Enthralled by sailing and the sea, young Cassin received an appointment to the Naval Academy and graduated in 1916. Like most naval officers, he would be given divergent assignments to familiarize himself with the Navy’s many tasks.

Young’s first posting was to the battleship Connecticut (BB-16). He served several years aboard submarines, then was posted to Naval Communications ashore, and also taught at the Naval Academy. In 1931, having risen to the rank of lieutenant commander, he was assigned to another battleship.

In 1933, he was given his own command, the aging destroyer Evans (DD-78). Assigned to the Pacific Fleet, Young would take Evans as far afield as Alaska and Hawaii. In 1937, he was promoted to commander and placed over a division of submarines in Groton, Connecticut.

Young next took command of Vestal. A crew member later remembered his arrival. “He said to me, ‘Hello, sailor, how are you doing?’ I said, ‘Fine,’ and we had a nice chat. He was making the rounds getting acquainted with the ship and meeting the crew.” They would never forget him.

On the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, even before the sirens blared for general quarters, Young had reached the bridge. It was clear that Pearl Harbor was under attack. He ordered the engineering officer to work up steam to get the ship moving. From there, he rushed to one of the ship’s three-inch guns, organized its crew, and directed its firing at incoming Japanese planes. The bombs from two of those planes missed the Arizona and hit Vestal instead. One bomb pierced the deck on the starboard side and exploded near the hull.

As Vestal took on water, Arizona was hit again by a bomb near the forward magazine, causing an explosion that wrecked the bow of the ship.

The blast blew 100 men off the decks of Arizona and Vestal, some of them in pieces. Young was among those in the burning oil-soaked waters. The intense heat from Arizona started fires on the smaller ship. With Young overboard, the ranking officer on the bridge gave the order to abandon ship.

Men rushed out of their duty stations. Some jumped overboard and swam, and some were picked up by a passing barge. Young made his way back aboard his ship. Seeing his men trying to leave, he ordered them, at the top of his lungs, to man their posts or help put out the fires. When the engineering crew came on deck from the engine room, they were ordered to return and build up steam—a difficult task because several of the steam lines had been broken.

Young then ordered that the ship be cast off from the burning Arizona so it could get underway. This order was not immediately obeyed because Vestal crewmen were helping Arizona survivors.

Time was precious, because Arizona was sinking and the mooring lines would take Vestal down with her. Once cast off, Vestal had just enough steam to cross the channel as her list to starboard increased, and settle onto a shallow mud bank. It was a good thing because for the next four months, Vestal would be the most important ship in harbor.

Vestal’s first task began immediately as its crew and equipment worked to rescue men trapped inside the hull of the capsized battleship Oklahoma. From there, the repair work seemed to never end as her crew worked overtime to repair other ships while she remained beached.

All the while, the Navy brass were aware of Young’s heroism in saving his ship and the invaluable service it had played in repairing or salvaging the damaged fleet. In February, Young was promoted to captain, and on April 18, 1942, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, was piped aboard the still beached Vestal to present Captain Young with the Medal of Honor for his actions during the attack.

The Medal of Honor citation reads in part, “Vestal was afire in several places, was settling and taking on a list. Despite severe enemy bombing and strafing at the time, and his shocking experience of having been blown overboard, Commander Young, with extreme coolness and calmness, moved his ship to an anchorage distant from the U.S.S. Arizona, and subsequently beached the U.S.S. Vestal upon determining that such action was required to save his ship.”

The citation should have mentioned that Young’s ship and crew were vital to the restoration of several of the ships damaged in port during the Japanese attack. In addition to the promotion and Medal of Honor, Young received a prestigious new assignment. He was posted as Captain of the heavy cruiser San Francisco.

Young took over his next command by November 9, 1942. It is not clear whether he was in command of San Francisco during the confused Battle of Cape Esperance, which took place on the night of October 11-12, just north of the embattled island of Guadalcanal.

Young was definitely in command of San Francisco for the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on the night of November 12-13, 1942. If, indeed, he took command on November 9, he had little time to acquaint himself with the ship or its crew. In any event, he was not fully in charge of the cruiser during the mid-November battle. It was now the flagship of Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, who himself had once been the captain of San Francisco.

It was a dire time for the Americans. Japanese ships were able to bombard Henderson Field on Guadalcanal at night with seeming impunity, while landing reinforcements and supplies in preparation for a major assault on Marine positions around the airfield. At sea, the Japanese had sunk the aircraft carriers Wasp and Hornet. Only the badly damaged Enterprise could still launch and retrieve planes, but had only one working elevator. Forty crewmen from Vestal were aboard Enterprise making repairs during this time.

Enterprise and her silent escorts steamed southwest of Guadalcanal and staged her fighter planes over Henderson Field in both directions so as not to lead pursuing enemy planes to the vulnerable aircraft carrier.

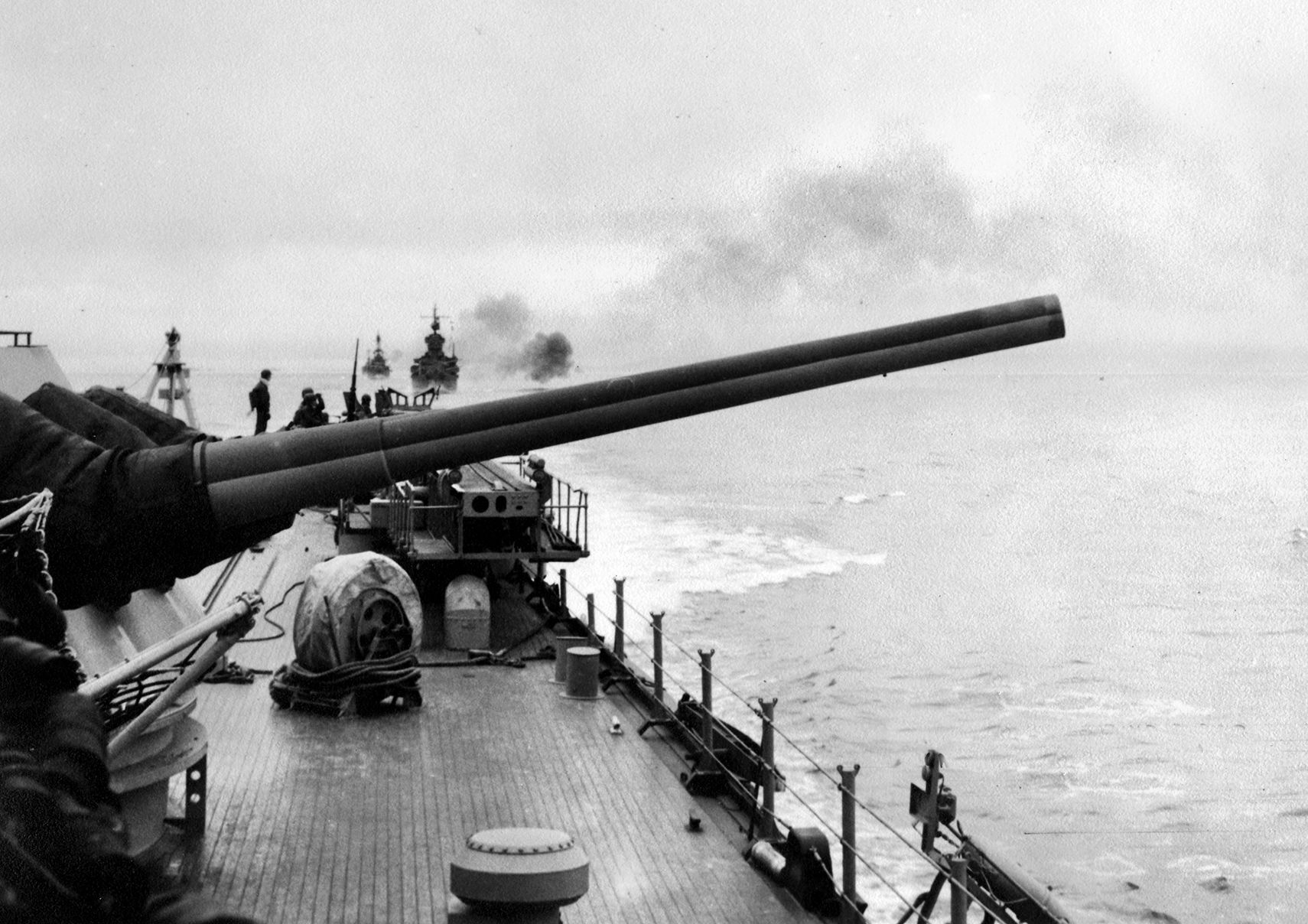

The Japanese were making another reinforcement and supply run to Guadalcanal in November. Long-range American reconnaissance planes discovered the enemy ships and warned the defenders of the island. A hastily gathered task force of two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and eight destroyers was assembled to stop them.

The Japanese task group, which included slow transports carrying 7,000 troops and their equipment, was protected by two fast battleships, one light cruiser, and eleven destroyers. Their orders were to deliver the troops, then bombard Henderson Field. Not expecting naval opposition, the Japanese had preloaded their guns with “san shiki”—an exploding shell that scattered shrapnel over a wide area—meant to devastate Henderson Field and its parked aircraft.

The hastily assembled U.S. Navy flotilla steamed in line northward toward the channel dividing Savo Island from Guadalcanal —nicknamed “Ironbottom Sound” due to the many ships sunk there fighting for control of the southern Solomon Islands.

Five of the American ships carried the new state-of-the-art SG radar, but Callaghan did not place these ships in the vanguard of his task force and did not select any of them for his flagship. He chose San Francisco, which was not equipped with the new radar, because as her former skipper, he knew the ship and her crew. For steering the ship and the care of its day-to-day operations, Callaghan relied on Captain Young.

Steaming through a rain squall with poor visibility as they approached the islands that night, the Japanese ships inadvertently split into small groups on their final approach to Guadalcanal. American radar operators, who reported several columns of enemy ships, were confused. When the two hostile fleets finally sighted each other in the dead of night, around 1:30 a.m., the Japanese found themselves moving along both sides of the single-file column of U.S. ships.

The hastily assembled American task force suffered from communication breakdowns and lack of a coordinated battle strategy. Without a plan, each ship found itself fighting alone against any enemy ship it could target in the chaotic close-quarter slugfest.

Superior Japanese optics, extensive pre-war night fighting exercises, and the superb Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo gave an advantage to the Japanese. However, the preloaded san shiki shells could not penetrate the thick-hulled American cruisers, forcing them to hurriedly use up this ammunition to make way for armor piercing rounds. Then the fight became bloodier.

Some ships turned on their search lights to illuminate the enemy, turning themselves into targets. Friendly fire added to the confusion. The Hiei, a 36,600-ton Japanese battleship mounting 14-inch guns, was swarmed by three American destroyers that fired away at her from close range. Hiei could not adjust her guns to fire on the close-in destroyers. Instead, the battleship’s gunners focused their fire on San Francisco, which was passing within range. Hiei’s bridge took a hit from either the destroyers or the San Francisco, seriously wounding Admiral Hiroaki Abe.

Due to the fog of battle, what happened next is not precisely known. The bridge of the San Francisco was destroyed by a shot from either the Hiei, or the battleship Kirishima coming up directly behind her. The hit was most likely made by a high explosive shell whose shrapnel tore through the thin armor protecting the bridge— instantly killing Admiral Callaghan, Captain Young, and most of the bridge personnel.

Not long afterward, the two sides ceased fire and disengaged. It was a tactical victory for the Japanese, who did more damage to the American ships than was done to them. However, Admiral Abe chose to declare victory and depart without landing the reinforcements and supplies—and also without bombarding Henderson Field, giving the Americans a strategic victory at the cost of their damaged ships and men like Young. The gallant officer would be awarded a posthumous Navy Cross, and the citation read in part, “Captain Young contributed largely to the success of the battle and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

In 1943, a Fletcher-class destroyer was named for Cassin Young, and the warship survives today as a museum and memorial at the Boston National Historical Park. In the city of San Francisco, a memorial erected for those lost aboard the namesake heavy cruiser. Located at the Lands End area of the city, the memorial uniquely includes portions of the shot-up bridge where Young was killed. The memorial is oriented in the direction of Guadalcanal.

Glenn Barnett has published more than 30 articles on World War II. He has worked in aerospace on the Apache Helicopter, B-1B bomber and several space craft programs.

An American hero.