By Eric Niderost

The giant Martin PBM-3R “Mariner” landed with a kind of swanlike grace, its stubby bow parting the waters, transforming them into a series of white and foamy ripples that radiated from the seaplane’s wake. Captain William W. Moss Jr. was at the controls, and once the initial landing was completed he taxied the Mariner over to the dock area. Moss had landed at Fiji in the South Pacific, part of a supply and transport assignment that originated in Hawaii.

The Martin PMB-R, formally designated Flight V2163, was part of the Naval Air Transport Service (NATS), whose mission was to keep the U.S. armed forces well supplied over the vast reaches of the broad Pacific. The seaplane’s ultimate destination was Noumea, New Caledonia, where medical supplies and personnel would be offloaded.

A Rough Water Rescue

It was just after 10:30 in the morning, but at that moment Fiji did not look like the tropical paradise depicted on colorful postcards and celebrated in Hollywood movies. The weather was bad, with rain-laden, slate-gray clouds hovering over Fiji like harbingers of doom. Before Moss could complete his taxiing maneuvers a message crackled from the plane’s radio phone. It was a call from Lt. Cmdr. A.L. Mare, who commanded at Fiji.

Indeed, the message was so urgent Mare did not have the time to wait until he could meet the Martin Mariner pilot face to face. A few hours earlier, at 5:30 am on Thursday, November 11, 1943, the troopship SS Cape San Juan had been torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Details were sketchy, but there had been around 1,400 souls aboard. Rain squalls lashed the area, and the seas were rough. Many of the men might well be in the water, and it was not clear if rescue ships could arrive in time.

Mare asked if the Martin Mariner seaplane might help. The stricken vessel was about 300 miles south of Fiji. Moss quickly agreed but felt he could take volunteers only among his own crew. In the 1930s and 1940s, flying boats were objects of adventure and romance, but behind the glamorous image there was a hard truth: seaplanes were not designed to land and take off in the rough seas of the open ocean.

Moss assembled his crew and told them what he knew. “I’m not ordering anyone to go,” he declared. “The weather’s foul—we’ll be lucky if we even find the ship….” His crew listened intently, taking in every word. “The Navy tells me,” he continued, “the seas are running 12 to 15 feet out there, and I’ve never set one of these tubs down in that kind of water. If we do get down in one piece, remember we still have to get back into the air.”

The whole flight crew volunteered, but to save weight three junior officers were left behind. After that was settled, the crew worked feverishly to convert the Martin Mariner from a cargo plane into a rescue aircraft. All possible running gear was stripped from the cabin and the cargo was quickly put ashore. The seaplane’s fuel tanks were topped off, and extra life jackets, life rafts, manila line, blankets, and medical supplies were stored aboard. Some hot soup was also carried, since the ship survivors were bound to be chilled after being immersed in the cold Pacific water.

“If You Need it, Use it”

Just before the final departure, a Navy captain asked Moss if he could go along on the rescue mission. The chief pilot had to respectfully decline because the officer’s extra weight might mean one less survivor would be rescued. Undaunted, the captain handed Moss five bottles of I.W. Harper Kentucky Straight Bourbon whiskey. This top-grade liquor was originally destined for none other than Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, commander of the Third Fleet.

The Navy officer, pressing the bottles into Moss’s hands, said, “If you need it, use it.” But now it was time to take off, and the Martin PBM-3R left Fiji at 12:39 pm. Minutes into the flight Moss was ordered to abort the mission, but he requested that they be allowed to proceed. At 12:44 permission was granted, and the flight continued. Every man aboard the Martin Mariner knew the risks involved, but the mood was nevertheless upbeat.

“A War of Supply”

The stricken ship and the Navy seaplane coming to its rescue had much in common, in spite of the obvious differences. Both performed services that were vital to the war effort, namely ferrying personnel, medicines, machine parts, and other supplies to battle fronts across the globe. Human nature and human history tend to focus on great battles and grand strategies. But without supplies— the vital sinews of war—victory would be impossible.

Frank Knox, Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Navy, once said that World War II was “a war of supply.” This was especially true of the Pacific Theater, where logistics were complicated by geography. The Pacific is the greatest body of water on the planet, encompassing some 64 million square miles of open sea. Islands speckle its surface, from the continental vastness of Australia to tiny atolls barely rising above the water.

The NATS was founded a few days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, the United States had few long-range cargo/transport aircraft. In fact, the only aircraft that did the California to Hawaii run on a regular basis, some 2,400 miles in all, were the civilian flying boats of Pan American Airways. Pan Am’s Boeing 314s and Martin 130s, generically remembered as the China Clippers, were quickly pressed into service for the duration.

Other seaplane types were added to the NATS’s fleet, including the Consolidated PB2Y-3 Coronado and the Martin PBM-3R Mariner. The “PB” designation stood for “Patrol Bomber,” a name that was retained even when the aircraft was used solely for transport. “Y” was the Navy’s code for Consolitated-Vultee, and M, of course, stood for “Martin.”

The NATS grew rapidly, and by 1943-1944 it had 200 planes and 8,000 men. The service spanned the globe, transporting 22,500 priority passengers and 8,300,000 pounds of cargo a month. Shipments might include periscope elements for submarines, generator parts, aircraft engines, plasma, or drugs.

The U.S. Maritime Commission, founded in 1936, played a crucial part in building cargo ships for the war effort. Perhaps the most famous type of cargo vessel was the Liberty Ship, created under the direction of industrialist Henry J. Kaiser. Thanks in large part to prefabrication, construction times were reduced from 250 days to a mere 25 days.

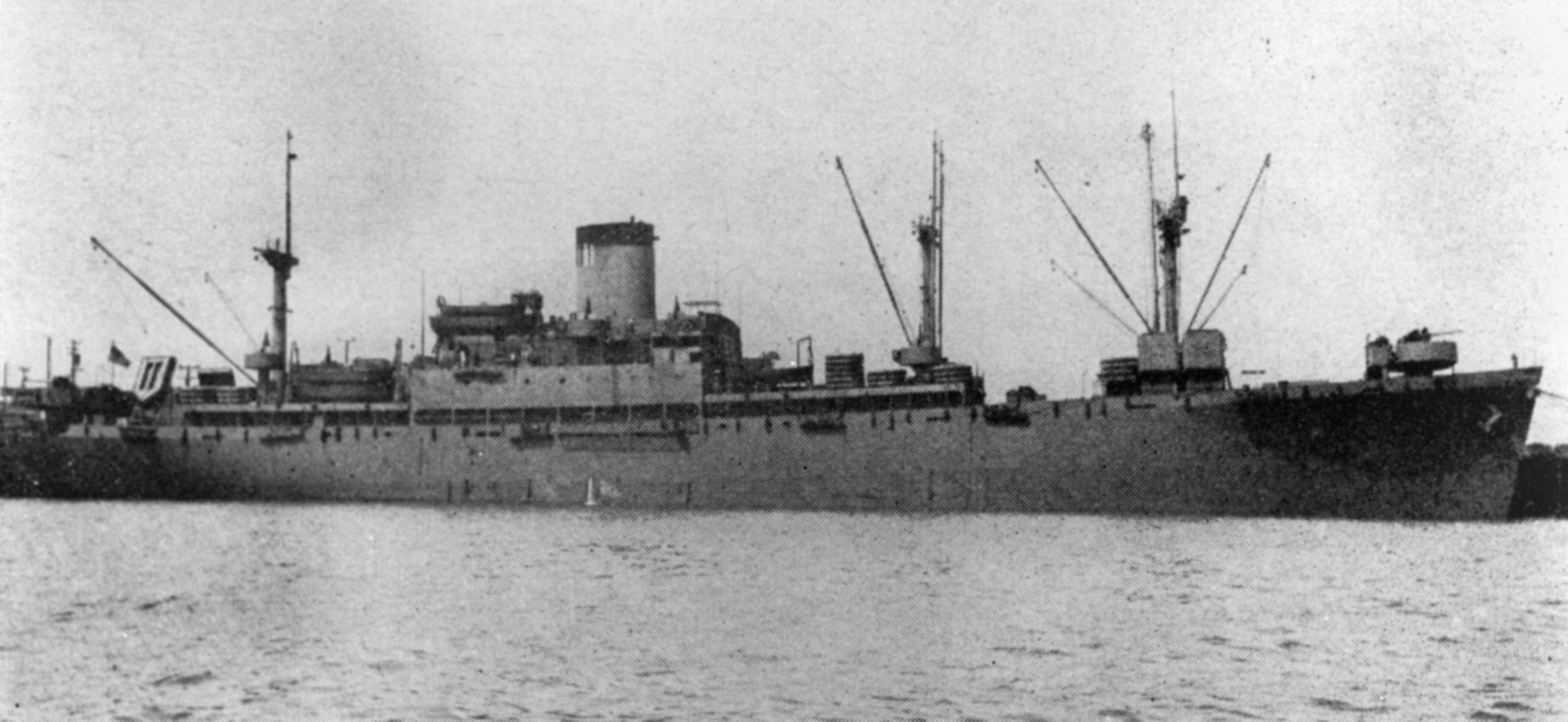

The SS Cape San Juan

The SS Cape San Juan was not a Liberty Ship but a dry cargo freighter type known as a C1-B. The C1-B was about 24 feet shorter, three feet wider, and 3,000 deadweight tons smaller than a Liberty Ship. The basic design had to be modified for war use. This included adding additional external deck structures, defensive armament, lifeboats, and rafts. Cargo holds were converted into living space with multi-tier bunks to accommodate troops. With these various additions, a typical C1-B could accommodate between 1,300 and 2,000 passengers.

The Cape San Juan was a new ship, delivered to the Hawaiian-American Steamship Co. on June 10, 1943. It completed only one trip before setting out on its fateful voyage. Cape San Juan departed San Francisco on October 28, 1943, its scheduled destination Townsville, Australia, a distance of roughly 7,000 miles.

A Long Passenger Roster

There were some 1,464 people on board, a number that was still below the ship’s maximum carrying capacity. The roster included the 57 civilian seaman crew, three radio operators, 42 Naval Armed Guardsmen (they operated the defensive guns), and 1,340 passengers. The passenger list was composed of three units of the Army Air Corps: the 885th “All Negro” Engineers (Aviation) Battalion, the 1st Fighter Control Squadron, and the 253rd Ordinance (Aviation) Company.

The 855th Engineer Aviation Battalion, 811 officers and enlisted men, was a segregated unit typical of World War II. In keeping with a racially motivated tradition that dated from the Civil War, African Americans could only serve in “all Negro” units under the direction of white officers. In any event, the 855th’s main mission was to build and repair landing strips. As soon as Pacific islands were secured, such sites often became bases for fighters and bombers.

The 1st Fighter Control Company, with a complement of 367 officers and men, was a ground radar unit. They were among the very first formations to hit the beach during amphibious landings on Japanese-held islands. Once in place, they set up radar, cryptographic, and radio connections between land, sea, and air forces. Among other vital missions, they provided early warnings if the Japanese attempted to launch air strikes on Allied forces.

The passenger roster also included the 23rd Ordnance (Aviation) Company, 182 officers and men in all. Ordnance men were responsible for the maintenance of guns, bombs, torpedoes, and other munitions. They would also be on hand to stow munitions. They also serviced airplane bomb racks and performed other similar duties. The list was rounded out by 21 Army personnel, three officers and 18 enlisted men commanded by transport officer Major R.A. Barth. There was one civilian aboard as well.

Well-Equipped and Skillfully Captained

The first two or three weeks of the voyage were fairly uneventful. Cape San Juan’s route was considered behind the lines, though the ship was always alert for danger. The ship faithfully followed all the precautionary rules, such as night blackouts and steering a zigzag course. Allied air patrols frequented the area, providing an additional measure of safety, or so it seemed. There was a relaxed mood aboard the ship, and there was even the opportunity to perform the time-honored “induction” ceremony for those who were crossing the equator for the first time.

Certainly, Cape San Juan was lucky to have an experienced sailor at the helm. Captain Walter Strong, 58, had been a seaman for most of his life. Like many sailors of his generation, he had started in sailing ships, and he knew the ocean’s many moods. He was not one to panic and was seasoned enough to know what to do in an emergency.

In fact, Strong was anything but complacent. The blackout was rigorously maintained, zigzagging proceeded as usual, and the armed guard gun crews were at general quarters. Cape San Juan was protected by three 3-inch 50-caliber guns, one 4-inch 50-caliber gun, and eight 20mm guns.

Struck by a Japanese Torpedo

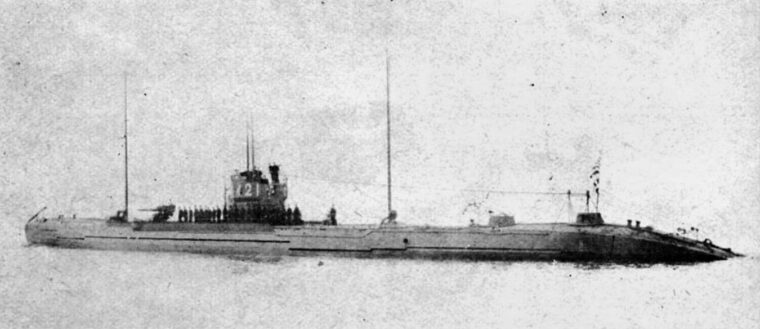

In the predawn hours of November 11, 1943, Cape San Juan was moving south at a speed of 14.7 knots. Though it was November, at 5:30 am it was still light enough to see clearly. Suddenly, lookouts saw a periscope and at the same time spotted the telltale wake of a torpedo. It was the Japanese submarine I-21, commanded by Hiroshi Inada, but the lookouts could do nothing in the few seconds before torpedo impact.

The torpedo stuck at the aft end of the No. 2 hold just as the ship was executing a turn to starboard, part of the usual zigzag pattern. Tragically, this was exactly where the men of the 855th were lodged. There was a terrific explosion, a blast that sent a gray-white plume of oily water high into the air, higher, in fact, than the stricken ship’s bridge.

The force of the blast carried No. 2 hold’s hatch covers high into the air, but then they collapsed into the hold itself, killing several men. The Japanese submarine fired a second torpedo, which narrowly missed the Cape San Juan. The explosion was so powerful Cape San Juan was actually slightly lifted out of the water. The vessel began to take on a list and to go down slightly by the bow.

The ship’s armed guard sprang to life, aiming its guns at the submarine’s last known position, about 3,000 yards out. The 3-inch and 4-inch guns fired round after round, great spouts of white smoke pouring from their muzzles with each discharge. As soon as a gun fired, wisps of smoke curling from its breech, the gun crew rammed in another round with clockwork precision. The 20mm guns also opened up, firing a total of 1,000 rounds at the elusive foe.

“All Stop”

Immediately after the ship was hit the order was given for “all stop.” For the moment, Cape San Juan was dead in the water with a pronounced 15-degree list to starboard. Within about 15 minutes Captain Strong ordered “abandon ship.” The events of the next hour or so are controversial, with some survivors claiming Strong’s evacuation order was premature.

Some of the controversy is hindsight; at the time, there was a real fear that the submarine might try and finish the vessel off with additional torpedoes. The weather was far from perfect, and the seas were running a rough 15 feet with periodic whitecaps. About an hour and a half after the first torpedo hit, a dull thud was heard, followed by an underwater explosion that caused the ship to vibrate. In retrospect, this probably was another torpedo strike, which was fortunately only a glancing blow. This ricochet apparently did no further structural damage.

Initial casualties from the blast and debris fall will never be adequately known. Most estimates place the number at about 16 to 20 killed, relatively light considering the ship’s full passenger and crew complement. A number of men showed extreme courage trying to save the wounded at the risk of their own lives. Several officers, including the 855th’s commander, Captain Herbert Edward Bass, lent a hand in rescuing or aiding wounded men in No. 2 hold.

By this time, No. 2 hold was a fearful place, a labyrinth of oily water and twisted steel, where weakened bulkheads, pipes, and other obstructions might well give way. Unwary divers might have their legs caught by unseen underwater debris, but danger was forgotten when lives were at stake. Bass and an enlisted man, Private Monroe Barkeley, dove into the shattered hold to tie a rope around wounded soldier Theodore Harris. Once the rope was in place, rescuers hauled the injured man to relative safety.

A Controlled Evacuation

In the meantime, Cape San Juan was being evacuated. There were six lifeboats (in peacetime the standard was two), four wooden rafts, and 36 Carley floats of various capacities. The Carly float was essentially an oval ring of kapok or cork covered in canvas, the ubiquitous life raft of many World War II ships.

The Army personnel did not panic, and the evacuation was later described as “controlled.” Nevertheless, in such situations things can and do go wrong. Some jumped ship in full combat gear and drowned. Apparently, some were killed when, once in the water, some of the lifeboats were launched in error on top of them. It is human nature to seek safety in a bigger, seemingly more stable vessel, so too many men made for the lifeboats. Lifeboat No. 4 became overcrowded and was swamped. Another came close to capsizing.

Some of the rafts, perhaps as many as six, drifted away in the high seas. Many of the men found themselves floating all but helplessly in the water with little to support them but their own personal lifejackets. Even the lifejackets provided little real comfort. Several of the men noted the lifejackets were stenciled with the warning “For Inland Waterways Only.”

There was little to do now but wait for help, and to the hundreds of men bobbing about in the shark-infested waters it must have seemed like an eternity. The moment Cape San Juan was hit an SOS was dispatched, but then the radio officer inexplicably ordered that the radio be destroyed. Though listing badly, the ship was still afloat, much to the chagrin of the survivors who were in the sea. Many were coated with oil, and some were half-blind from the sticky, viscous substance.

Finding the Survivors

A Royal New Zealand Air Force Lockheed Hudson coastal reconnaissance bomber arrived at 7:40 am, some two hours after the torpedo struck. After circling Cape San Juan’s position, it left, then returned to radio the ship that help was on the way. The Hudson was a conventional fixed-wing land plane that could not be of immediate assistance, but the sight of the hovering aircraft must have been heartening to the survivors in the water.

The Liberty Ship Edwin T. Meredith was the first surface vessel to arrive on the scene at 11 am, five and a half hours after the Japanese attack. The vessel combed the waters, circling Cape San Juan and pulling out as many survivors as possible. The Meredith crew did an outstanding job, but many survivors were drifting away in the white-capped seas and strong currents.

The Martin Mariner Arrives on the Scene

In the meantime, Captain Moss and his Martin Mariner seaplane were en route to the Cape San Juan site. The 300-mile journey was a long one, and they hit a tropical storm (Moss called it a “squall”) about halfway to their destination. Lightning crackled through the sky, rain pummeled the Mariner’s fuselage, and high winds buffeted the seaplane.

Throughout this rollercoaster ride the crew made final preparations for the attempted rescue. Pharmacist’s Mate A.C. Burress, a lastminute addition to the crew, was particularly busy. It was a rough ride, described by First Officer Frank Saul as “tornado tough,” but at last the battered seaplane emerged from the turbulence. Having literally weathered the storm, the Martin Mariner found itself about 10 miles from its objective.

Captain Moss and Second Officer Saul were at the controls trying to peer through thick cloud cover that partially reduced visibility. Saul later recalled, “We dropped down below the cloud cover and—boom!—there they were. The ship was listing to starboard, obviously sinking. We went around, circling three or four times….”

There were men still aboard Cape San Juan, perhaps 200 out of the original 1,464 men originally with the ship. The ship was obviously badly damaged but did not seem as if it was going to sink immediately. Since the ship seemed stable for the moment, Moss thought of the survivors bobbing helplessly about in the rough seas. But there did not seem to be anyone in the water. Currents and waves had scattered lifejacketed survivors for miles.

Then Moss spotted two RNZAF Hudsons circling a patch of ocean about eight miles away. The captain decided to investigate. At first all Moss and Saul could see was a thin black ribbon that stretched for three or four miles. This was an oil slick from the ship. When they looked closer, they could see that the slick was speckled with black dots, the Cape San Juan survivors.

It was a moment for careful reflection. Moss turned to Saul and said, “Well, what do you think?” Saul answered, “Well, what do YOU think?” Both men, veteran pilots, knew the problems they faced. The seas were rough, running at a good 15 feet. If the seaplane landed into the wind as it normally did, the Martin Mariner would be hitting the white-capped waves.

The effect would be, in Moss’s words, like that of a “bucking bronco.” The only alternative was to land cross wind, which violated every rule in the book. Moss hoped he could “stick one wing into the side of a wave” and thus have a relatively safe, if not smooth, landing. Time was running out. A decision had to be made. Moss courageously opted for the cross-wind landing.

“It was a Pretty Rough Landing”

Moss took the controls and guided the seaplane in at 70 knots. For one breathless moment it seemed the captain’s gamble paid off, and then the Mariner hit a wave that rudely bounced it back into the air a good 50 feet. Moss manhandled the throttles and held the elevators back as the plane collided with a series of waves. The Mariner shuddered violently as wave after wave slammed into the plane’s rounded nose.

The sledgehammer blows tested the endurance of both seaplane and pilot; Moss later said he was certain he heard glass breaking, and in his mind’s eye could imagine seawater pouring into the interior. The Mariner successfully came down, with a relieved Moss admitting, “It was a pretty rough landing.”

Moss ordered a structural check, and all seemed okay. But there was no guarantee that the seaplane could take off again, especially if loaded with survivors. For the moment, Moss and his crew set aside any doubts and fears and prepared to rescue as many Cape San Juan survivors as possible.

Reeling in the Survivors

But Captain Moss was confronted with a new set of problems. The survivors were scattered in every direction, and if the Mariner taxied after them they might well be hit by one of the seaplane’s spinning propellers. The survivors had been in the water for nine hours by then and were too exhausted to swim. Radio operator Don McKay and steward Kennie Taylor inflated a life raft and attached it to a 100-foot rope. Next, they tossed the lifeboat into the sea, playing out the line to its maximum length.

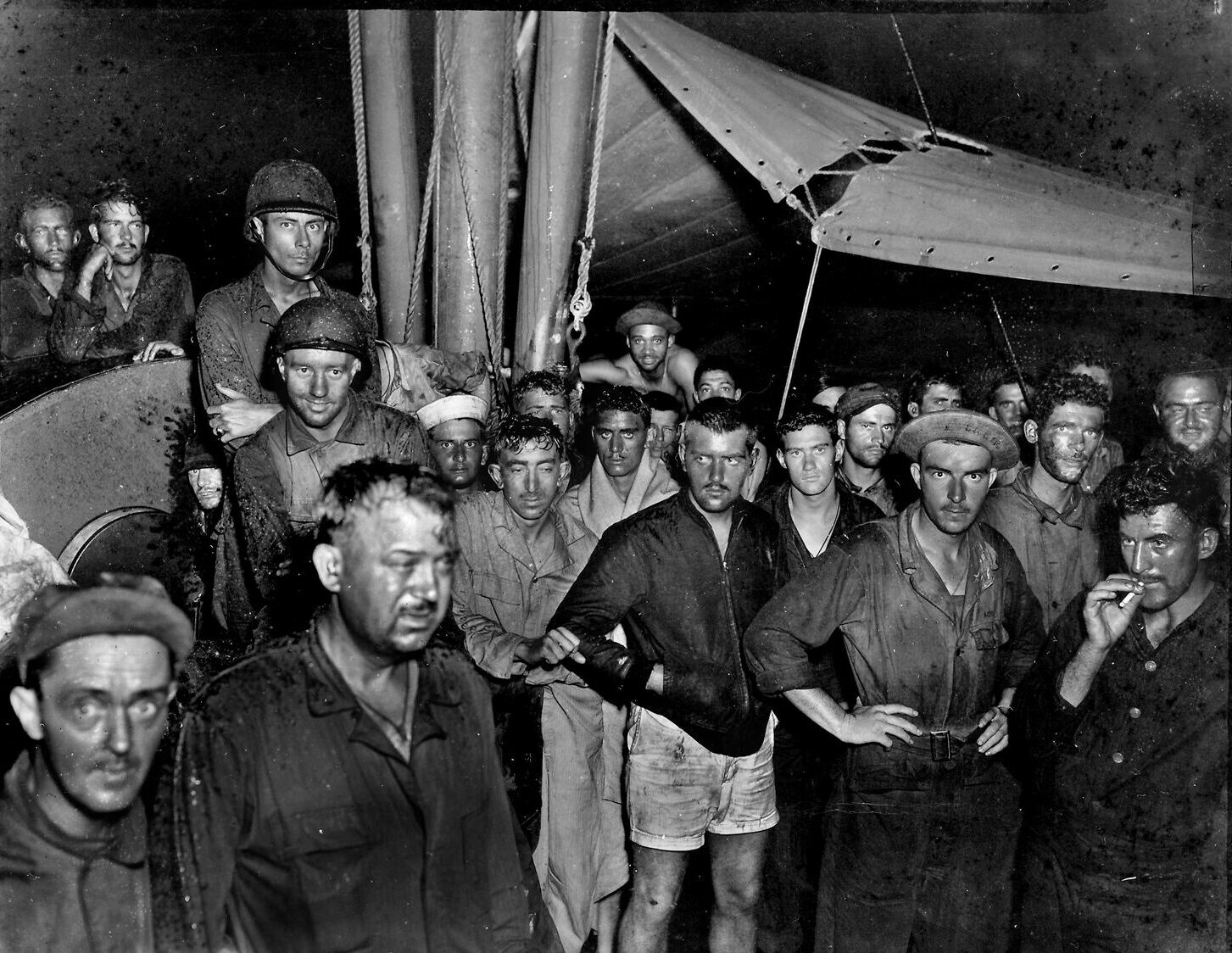

“We zigzagged upwind,” Moss remembered, “trailing [the line] behind us, and all survivors who came in contact with the line worked their way down to the raft.” When the life raft was full, the Mariner crew hauled the rope in like a fishing line and collected the men on the raft. When the last survivor was hauled in, the raft was returned to the sea for another load. Once aboard, survivors were given first aid if needed, then supplied with blankets, hot coffee, hot soup, or even a shot of the admiral’s whiskey.

The Mariner continued hauling in survivors for about two hours. It was exhausting work because the survivors were dead weight from weakness and slippery because they were covered in oil. Then, as Moss later recalled, “Suddenly, I saw one of the New Zealand planes fire two red Very shells. I didn’t know why—but red means danger. We were a nice target for any lurking submarine.”

“Hairiest Takeoff of my Life”

It was time to go in any case. The air crewmen were exhausted, and there were 48 survivors aboard the seaplane. Counting the crewmen, there were 55 people on the Mariner, twice the maximum load. Moss was the son of Supreme Court Associate Justice William Moss, and as a jurist the father was used to handing down important decisions. Now the son was faced with his own decision, this one a matter of life and death.

How was he going to get the overloaded Mariner into the air again in rough seas? First, Moss jettisoned the auxiliary gas tanks to lighten the load. As it was, the seaplane was still overweight, with an estimated 45,258 pounds. Moss’s flight path was also relatively narrow, with little margin for error. Another rain squall threatened on the right, and on the left more survivors bobbed about.

Moss took the controls and started forward, bringing the Mariner to 55 knots, but as the seaplane lifted off it hit the top of a wave, a collision that bounced it into the air 50 or 60 feet. The heavy seaplane was still not airborne but continued to bounce the ocean swells like a thrown rock skipping over a pond. After five or six bounces the plane finally was airborne at a speed of 70 knots. The whole takeoff took only 50 seconds, but it must have seemed like an eternity to the men aboard.

It was still a near-run thing, and at one point the wing had dropped 20 degrees before being righted again. Captain Moss later recalled that it was the “hairiest takeoff of my life.” Second Officer Saul concurred, saying, “It was the longest 50 seconds of my life.”

The Mariner successfully made it to Suva, Fiji, where the survivors were offloaded and given medical care. As a civilian pilot of the NATS, William Moss’s employer was actually Pan American Airways. Since he was technically a civilian, he was not eligible for a medal, but his heroic flight did not go unnoticed and the Navy did give him a warm commendation letter.

Collecting and Treating the Survivors

The saga of Cape San Juan was not over yet. Other ships came to the scene to conduct search and rescue operations. The destroyer USS McCalla (DD-488), the minesweeper YMS-241, and the destroyer escort USS Dempsey (DE-26) were all involved at one time or another. Each of these vessels picked up what survivors they could find.

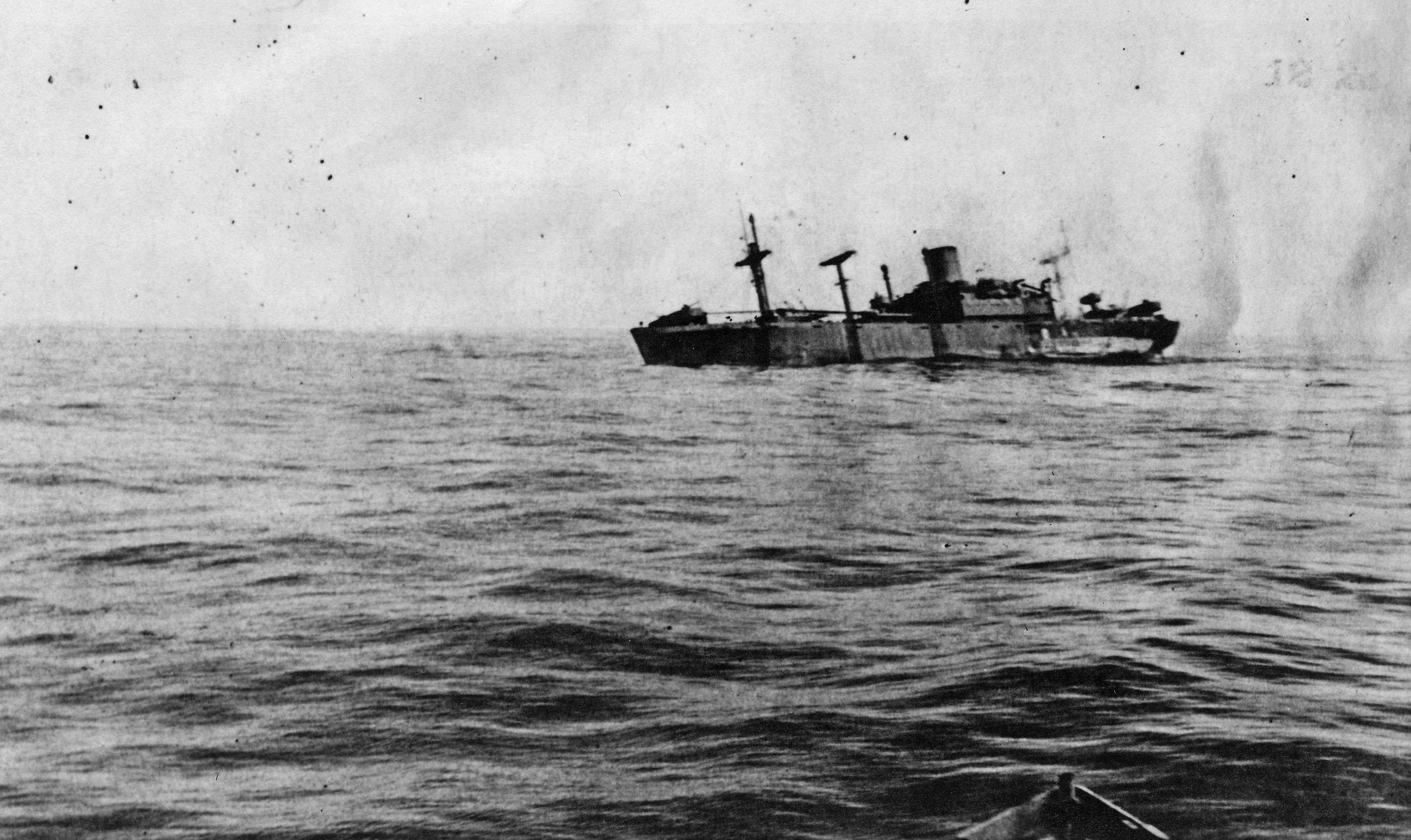

It was nearly 8 pm, over 14 hours after the Japanese attack, when the final crew members were taken off Cape San Juan by Edwin Meredith. In keeping with the ancient tradition of the sea, Captain Strong was among those last few people to leave the ship. Once aboard the rescue ship, Strong requested that the now abandoned vessel be finished off by naval gunfire.

The request was granted, and the Edwin Meredith’s aft 3-inch deck gun fired 12 rounds into Cape San Juan’s hull. The next day, November 12, the submarine chaser SC-1048 reported that Holds 2 and 3 were flooded and the ship was gutted by flames. It is not certain if the flames were ignited by the Edwin Meredith’s deck gun or by an earlier Japanese torpedo.

The battered Cape San Juan could take no more and started going down by the bow. Within minutes it was all over, the ship plunging some 1,400 fathoms to the bottom of the Pacific. It was the only ship of its type lost to a Japanese submarine.

The total number of casualties is difficult to assess. There were multiple commands aboard Cape San Juan, and several vessels picked up survivors. Some died aboard rescue ships and were buried at sea. When injured survivors did reach land, they were segregated according to race, a common practice of the period.

Finishing the Admiral’s Whiskey

When all available evidence is examined, probably about 130 men were killed, died of wounds, or drowned. A further 200 or so were injured but recovered and returned to duty. The prompt action and heroism of both the rescue ships and the seaplane crew had prevented a much larger catastrophe.

The sinking of Cape San Juan was a short-lived triumph for the Japanese submarine I-21. A little over two weeks later, on November 27, 1943, Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers from the escort carrier USS Chanango (CVE-28) sank a B-1 type Japanese submarine. I-21 had been in the area, and after November 27 it was never heard from again. Presumed lost, it was struck from the Japanese Imperial Navy roster in 1944.

When his Mariner returned to Fiji, Captain Moss dutifully returned what was left of the admiral’s whiskey to the naval officer who had sent it. There were two full bottles and one that was half full. The officer, eyeing Moss, impulsively gave the half-full bottle back to the seaplane pilot. “Here,” he declared. “You look like you could use it.”

Moss gratefully accepted, intending to share the gift with his flight crew. But by the time he was debriefed, his crew had all gone to get something to eat. Wearily Moss went to his quarters in a Quonset hut and sat down at the end of his bunk. Wasting no time, he finished the admiral’s whiskey himself. At that moment, he probably appreciated the drink more than a medal.

Eric Niderost is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He writes from Hayward, California, where he is also a college professor.

Thank you very much for your article. My father was a twenty year old survivor of the Cape San Juan. He didn’t speak a lot about war but did tell us he was temporarily blinded by the oil floating in the sea. He told us he could hear men being attacked by sharks and was terrified. He was picked up by the Merideth and went on to serve in three campaigns in the South Pacific earning three Bronze Stars. He also served in Korea and Vietnam Nam. His name was William H. Oliver. He was 5th Army Air Force.

My late great grandfather was a survivor of the wreck as well, growing up he told us how he had done something with his cap so that it didn’t get covered in oil so that we could still see, he shared many stories of the occasion and the war. His name was W.C. “Jeff” Jefferson (fun fact- a late descendent of Thomas Jefferson) i’m not sure exactly what medals he was awarded besides the purple heart or what he was stationed in.

My dad , Raymond Jones of Arkansas, was a survivor, picked up after 36 hours adrift. He was 21. An amazing story of survival & rescue, but many many stories of death at sea. Dad came back in 45, married my mom and they remained married until his death in 1998. They raised me and my two sisters, who obviously owe our existance on the planet to the rescuers. He went to many Fighter Squad reunions. His widow, my mom, died this week at age 96

Thank you for writing about this. My father, William Wallace of New Hampshire, was on this ship. Fortunately, he was taken to a hospital in Fiji. He would never talk about it. I think the worst part of this event were the terrible shark attacks on the men in the water. Not much attention was paid to those attacks in your writing. My dad returned home in 1945, married my mother, and the following May, I was born. I am so glad he was rescued!

My great uncle, PFC Porter J. Wyatt, was in the 855th Engineering Battalion. He was unfortunately deemed MIA after the attack. Just wish I was able to find out more about his story.

My father, Rudolph “Rudy” Wahlstrom was a merchant marine on the ship. His lifeboat floated away and was later picked up by the coast guard. My father said he was waiting to be gunned down by machine guns by Japanese but fortunately that never happened. He said the bodies and men eaten in the shark infested water was horrific. My father said one gentleman said “pull me in and I’ll Row like hell” my dad always Choked up when he spoke of it. He was a boiler and often spoke of a gentleman names Julian that was a fireman. Rudy went on to father 6 children in California then later fathered 4 children in Nebraska…. I’m his 10th

My uncle Stanton Morgan was in the 1st fighter squadron and spoke of being in a Carly float and the sharks saying he would never go in the ocean. He trained at Pinedale Calif. After recover from the oil on Fiji and Port Moresby he went on to serve on New Guinea calling in air strikes on Japanese and once hid for 3 days under a over turned wagon and laying in water as Japanese walked right by him as they searched for him. He passed away in the 1990’s and is buried in Clovis Ca.

So happy to see all the comments. When I began to compile the Saga of the 1st Fighter Control Sqdn I was in touch with 12 of the survivors. Sadly, all are passed today. Blessed to have known them.

My Dad, Charlie Craig Hanes, was on this ship – part of the 1st Fighter Control Squadron. He was sleeping on deck when the torpedo hit. Daddy shared his story of being in the water for 36 hours, realizing those on the rafts were sitting ducks should the submarine decide to surface – thankfully it didn’t. He personally didn’t see the shark attacks but his crew mates did.

After the war he married, raised his children, I am the middle child of 3. His wife, my mom, passed in 2000 – they were married 52 years. He retired as a machinist in 1983 after 36 years.

He attended many reunions with his military buddies – those have all since passed. Daddy could be the only one left, we’re not sure. Today he is 97, in relatively good health. He has been retired for more years now than he worked.

Thank you for this recap, Daddy read it all tonight. Thanks to all those brave rescuers, I wouldn’t be writing this without them.

My father in law, Pvt Reuben Howard was a member of the 855th and survived the attack of Cape San Juan, he spoke of the many who were lost to shark attack on that day, matter of fact it was the worse shark attack and loss of life second only to the USS Indianapolis at the close of the war. I find it deplorable that the Army did not outfit the ship with the correct floatation devices and this sinking and horrible tragedy was kept secret even after the war especially to the African American community. You can only find that there was the 855th but their story was never told. Shame on you Army and America!!