By Flint Whitlock

It took the HMS Queen Elizabeth, the world’s largest passenger liner, only five days to transport 15,000 men of the 106th Infantry Division from New Jersey to Glasgow, Scotland, making port on November 17, 1944.

The troops were then carried by trains to Portsmouth, England, and shipped across a storm-tossed English Channel to France. The young American soldiers of the “Golden Lion” Division who had hoped to spend a few days in Paris, liberated from German occupation just three months earlier, were disappointed. The men were loaded like cargo into hundreds of unheated trucks and hauled eastward, crossing into Belgium on December 10.

As they drove on, these young men with fresh faces were appalled at the scenes all around them—towns and cities wrecked by shells and bombs, burned-out tanks and trucks that lined the roads, temporary cemeteries here and there—that exceeded a thousand-fold what they had seen in newsreels or newspapers. War was now not just an abstraction; it was very real, and the Golden Lions were about to be thrust into it.

Maybe they should have been called the “Green Lions,” for they had yet to hear a shot fired in anger. They had gone through basic training and advanced infantry training, and learned the way of war, but they were far from being warriors; the shouts of drill sergeants could not compare to the ground-shaking booms of artillery that would soon be coming their way.

In the middle of December 1944, the Allies held a 400-mile front—from Nijmegen, Holland, in the north to the French-Swiss border at Basel, in the south. Occupying the northern end of the front were the British and Canadian Armies of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, while General Omar Bradley’s 12th U.S. Army Group were emplaced along the southern end.

Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’s First U.S. Army, to which the 106th Infantry Division was now attached, had the broadest sector to cover—from Aachen to the southern border of Luxembourg, a distance of 120 miles. To the north was the Ninth U.S. Army (Simpson) while to the south was the Third (Patton).

Making up Hodges’s First Army were the 2nd, 4th, 8th, 28th, 29th, 30th, and 99th Infantry Divisions, plus the 2nd and 9th Armored Divisions—most of which had gained valuable combat experience over the past six months and during the grueling Hürtgen Forest campaign.

The 106th Division was inserted into the line near St. Vith, along the Belgian-German border, with the 99th Infantry Division on its left flank and the 28th on its right. Because this was a “quiet” sector where little or no enemy action was expected, the Army felt that this would be the perfect place to position the division so that the inexperienced lions could become gradually accustomed to life on the front lines.

Although he was a veteran of World War I, the 106th’s commander Maj. Gen. Alan Jones had never commanded troops in combat before; he was as green as his men.

Through no fault of its own, the 106th was about as ill-prepared for combat as any division that America ever put into the field. While training at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, the 106th became a human quarry from which thousands of men were extracted and sent overseas to replenish divisions that had been hard hit in combat. It is estimated that, from the time of its activation in March 1943 until its deployment to Europe, the 106th had lost 80 percent of the men who started with it.

Once it arrived at the front, the 106th—and its the 442nd, 443rd, and 424th Infantry Regiments—had not had time to acclimate itself to its new positions. While the 2nd Infantry Division, which the 106th replaced on the line, had earlier plotted out preregistered artillery concentrations to its front, and established liaison with the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group to its north, the 106th had yet to adequately carry out either of these two essential tasks.

The officers of the 106th may have thought that, as new arrivals at the front, they would be given time to get their feet wet before anyone expected them to do any “real” soldiering. And they may not have realized that the division, in its positions in the Schnee Eifel region of the Ardennes Forest, represented a deep penetration into Germany territory.

The Allied high command had no reason to expect a German counterattack through this hilly, heavily forested area in the dead of winter. German deception plans convinced the Allies that they were content to hold their positions and stay on the defensive until at least spring. American intelligence had not spotted the build up of panzers and infantry forces that sheltered under the tall pines a few miles to the east.

Operation Wacht-am-Rhein

On December 11, a group of German generals was ordered to Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s headquarters at Langenheim-Ziegenberg, about 20 miles north of Frankfurt-am-Main. They were then loaded onto buses and taken to Adolf Hitler’s secret underground forward headquarters at the resort city of Bad Nauheim.

Hitler himself was there, looking old and haggard. After a long-winded historical discourse, he got to the point: in four days the German army would launch the biggest offensive since Operation Barbarossa—Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The new operation would be code-named “Wacht-am-Rhein.” His generals were aghast.

While it paled in comparison to Barbarossa, Wacht-am-Rhein still had plenty of power: three armies with 13 infantry and seven panzer divisions, plus five divisions in reserve, plus thousands of artillery pieces—a total of 290,000 men that would hit the thin American line being held by only 80,000 men on a front of 75 miles. In the direct path of the onslaught were the 99th and 106th Infantry Divisions. The date of attack, that would be known in the West as the “Battle of the Bulge,” was set for the night of December 15-16.

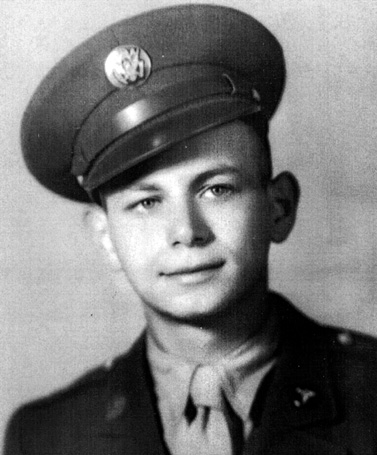

One of the “Green Lions” trying to stay warm while on guard duty was Pfc. Peter Iosso from Newark, New Jersey, and a member of Company E, 422nd Regiment, 106th Division. “I had been out in the snow from about 6 p.m. on December 15 until about 6 a.m. the next morning,” he recalled. “My equipment and clothing were still wet, freezing at night and thawing in the daytime. Winter gear, we were told, was on the way.”

Suddenly, a full barrage of German shells began saturating the front. A round exploded nearby and knocked Iosso unconscious. He awoke with a bloody chin and throbbing feet. “I managed to get to the company HQ,” he said, “where somebody bandaged my chin. But the battle had begun and the aid station was getting ready to retreat.”

Joe Mark, a radio-telephone operator from the Bronx, New York, was at his switchboard in an abandoned German pillbox that served as the headquarters for the 3rd Battalion, 422nd Regiment. “I was putting through calls from our artillery observer in the front to our artillery in the back,” he said. “Our position held initially. We stopped them cold in front of us, but they got around us on both sides.” Soon, Mark and the rest of the headquarters staff were falling back.

Mortarman James V. Smith, Company H, 423rd Regiment, learned on the morning of the 16th that the Germans had infiltrated the artillery positions of the 28th Division. He remembered, “We were supposed to go up to the front lines and chase the Germans out of the 28th’s artillery positions. But we started seeing three-quarter-ton trucks passing us, heading for the rear. We could see all these dead soldiers stacked up in the trucks. That didn’t cheer us up very much.” Suddenly, Smith and his unit were coming under assault by pilotless V1 “buzz bombs.”

To the north, the 99th Infantry Division was also being hit by the German attack. Clifford Savage, a member of the 99th, recalled that the Germans were wearing white sheets to camouflage themselves against the snow. Savage’s position was soon overrun and his unit was forced to surrender after their platoon leader was shot between the eyes.

As an SS unit took Savage’s unit, he said, “They searched us and we had to throw everything we had down on the ground—watches, money, everything. Then they made us take all the dead and wounded Germans back to their bunkers. We did that for maybe a couple or three hours.”

By late morning on the 16th, the 14th Cavalry Group was also being pushed back, uncovering the 422nd Regiment’s left flank. On the 423rd Regiment’s right flank, in the village of Bleialf, a street battle resembling a Wild West shootout—only this time with using automatic weapons, armored vehicles, and artillery—took place; the seam between the American units was torn. The German breakthrough above and below the 106th’s 422nd and 423rd Regiments was about to trap the division in a classic double envelopment.

St. Vith was in a panic, with civilians attempting to flee while German shells, fired from batteries in Prüm, 15 miles away, bombarded the town; German armored columns were spotted closing in. No one, least of all General Jones, seemed to know what was happening to the 106th’s forward regiments.

What was happening was basically a rout; soldiers were running for their lives, throwing their weapons away. The 106th, 99th, and 28th Infantry Divisions, squarely in the path of the German bulldozer, were crumbling.

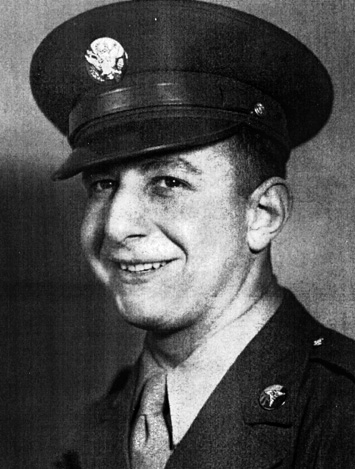

Combat medic William Shapiro of the 28th Division recalled, “After a bombardment by the enemy stops, you know that tanks and infantry are heading toward your position. The machine-gun firings, mortar shell bursts, and ‘Screaming Meemies’ are all around you as you dig deeper and deeper into your foxhole. You are helpless and alone. Suddenly, I saw a very bright flash of light in front and to the right of me. There was a deafening loud explosion.”

That’s all Shapiro remembered; he was knocked out cold by the explosion. He woke up several hours later in the Clervaux railroad station, his ears ringing and his head feeling like it would come apart.

He said, “Major Clyde Collins said that the Jewish soldiers should throw their dog tags into the potbelly stove in the center of the room because we were surrounded by SS troops.”

Shapiro complied with the order, but was puzzled. “I do not recall any thoughts about what this action meant, or even related the fact that I was Jewish and these were SS troops. I had not known of any incident in which Jewish soldiers had been shot.”

Along with the rest of the men in the station, Shapiro came out with hands up. Germans were shouting “Raus! Raus!” and firing weapons into the air. After being searched by members of the 116th SS Panzer Division, the Americans were relieved of their watches, gold rings, cigarettes, and anything else of value. The prisoners were then marched to a nearby hotel and locked in for the night.

The next morning the POWs were marched farther east, scattering off the road every time motorized German vehicles roared past, heading west. “All of us remarked at the shabbiness of the German equipment when compared to American troops on the march,” Shapiro recalled.

Complete Chaos

For the next several days, all was confusion and chaos in the American ranks as commanders tried to rally their troops and make a stand while higher headquarters was trying to bring in additional units to halt the German advance. Aircraft from both sides dueled in the air. A fierce snowstorm added to the mayhem.

Meanwhile, Joseph Mark and his unit had managed to escape capture for three days, but their freedom was about to come to an end. When finally surrounded by the enemy, he broke his rifle and gave up. “I thought that the war was over for me and that the worst was over,” he said, “but I was wrong. The worst was coming.”

The roads were packed with thousands of U.S. servicemen (some 8,000 Americans had been taken prisoner) being marched into Germany, many of them toward Prüm, a small city on the German side of the border.

Joseph Mark recalled, “They marched us back to a town called Prüm, where a German took my galoshes, and then they searched me. I had a little tin of Bayer aspirin and one of the guards was going to shoot me because Bayer is a German company and he thought I had taken the tin off a German. A German sergeant told him that Bayer was commonly distributed, so I wasn’t shot.”

The POWs were taken to the Prüm railroad station and locked into boxcars that soon began rolling eastward.

William Shapiro, the 28th Division medic, was herded with his POW group on a march lasting three or four days until they came to the railroad station at Gerolstein. He recalled, “This was the first time we were guarded by soldiers holding German Shepherd dogs on leashes.”

Pfc. Charles D. McMullan of the 422nd Regiment remembered, “I, along with several thousand others, were captured near St. Vith. We slept in a churchyard that night, and the next day we were walked to Gerolstein in zero [degree] weather and eight or 10 inches of snow, during which time I had my feet initially frozen.” From Gerolstein, McMullan would be taken to Stalag VII-A, the first of four POW camps in which he would be interned.

As with the POWs at Prüm, the GIs at Gerolstein were packed into boxcars for a trip to a prisoner-of-war camp.

Of his rail excursion, Joseph Mark said, “The boxcars were made with square wheels that were imported from Italy. It wasn’t a comfortable ride. They put 60 men in a boxcar and if you fell asleep, three or four guys piled on top of you. The toilet was in one corner of the boxcar. Not even a bucket—just the floor.”

Toilet facilities were also horrendous in William Shapiro’s boxcar: “Two simple boxes placed in the middle of the floor. The air was putrid and fecal-smelling and made worse by being confined in a very tight space. The stench was unbelievable. It led to arguments and fighting between the men as to when, where, and how to urinate and defecate.”

The foul smell in the boxcars soon became the least of the POWs’ worries as Allied pilots began bombing and strafing every train they saw traveling on German tracks; there was no way for them to know that the boxcars were filled with American GIs.

Ordeal at Bad Orb

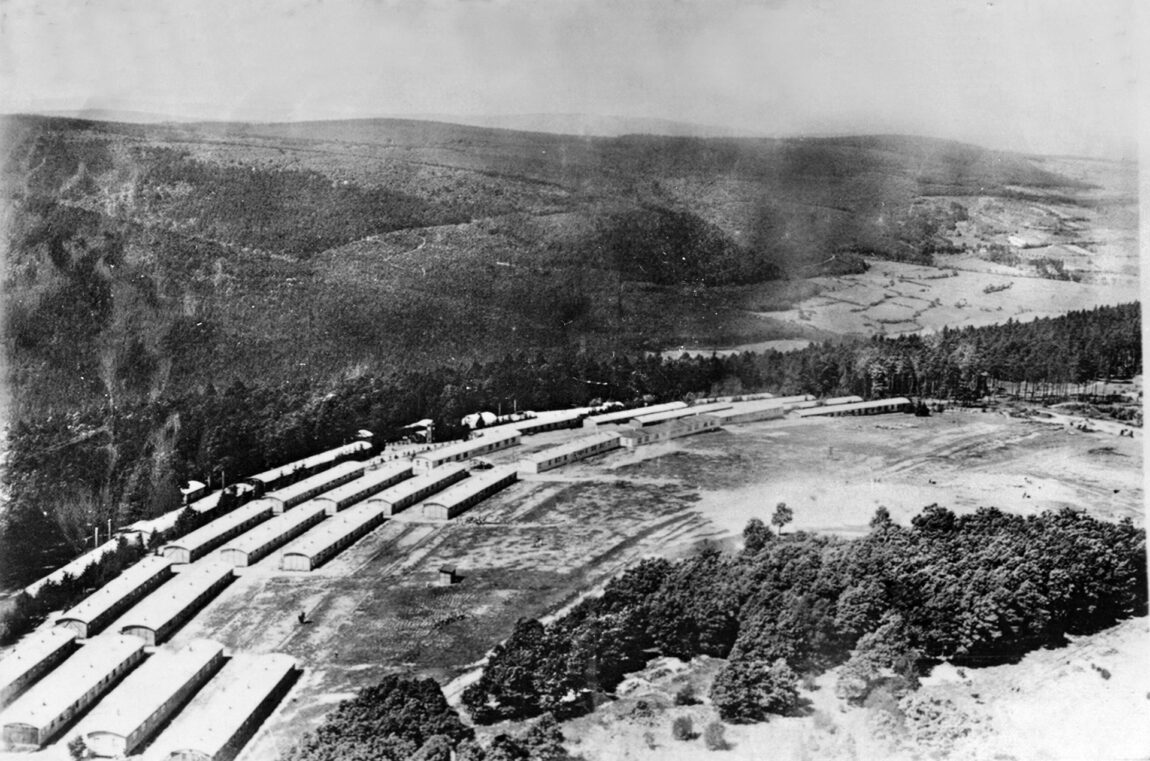

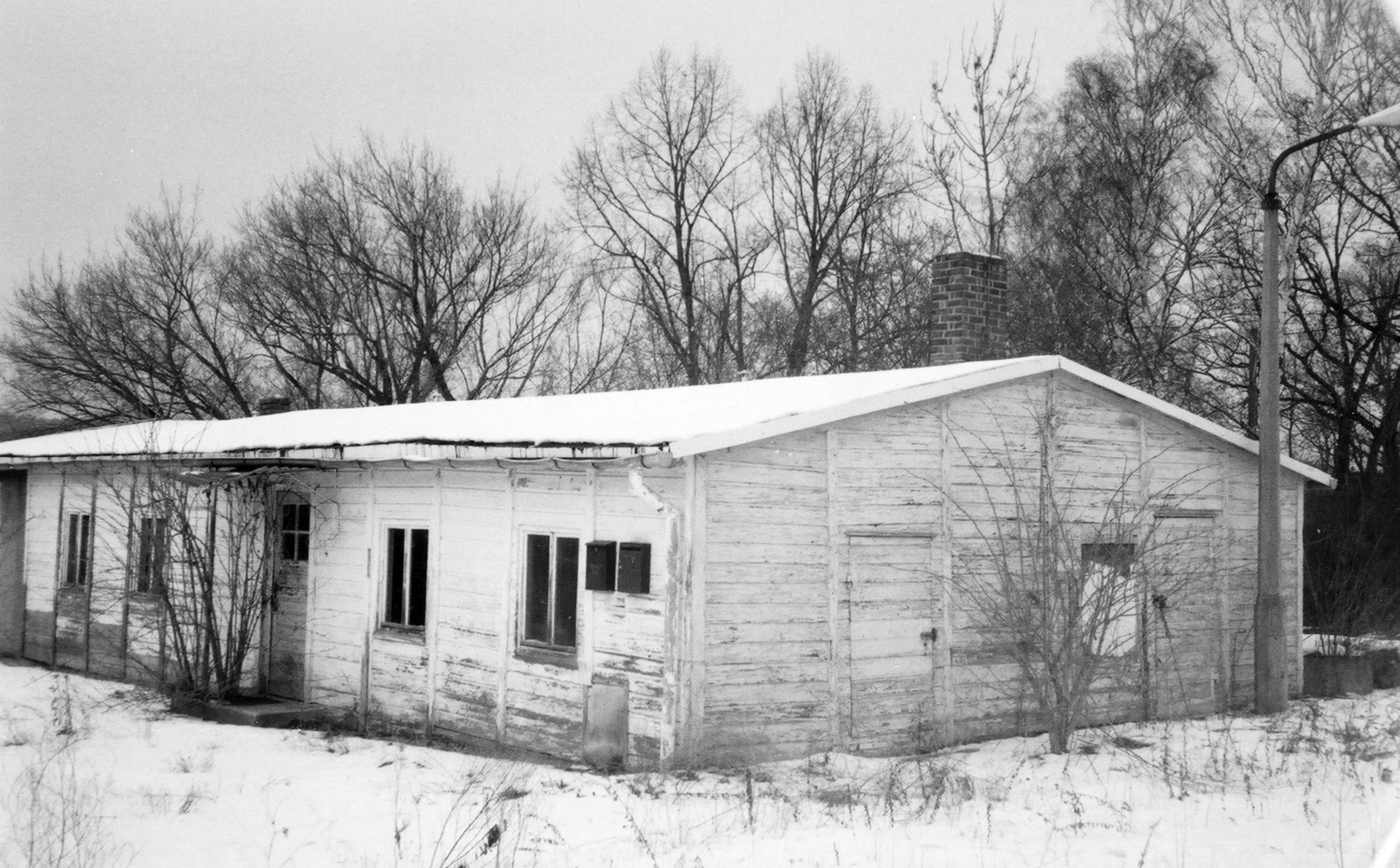

Trains packed with prisoners soon arrived at Bad Orb, a health-resort town in the snowy hills about 30 miles east-northeast of Frankfurt-am-Main. Here was Stalag IX-B, a POW camp that was one of the foulest in Germany, perched atop a hill that was once a children’s nature camp.

After descending from the boxcars, the half-frozen POWs were marched through the town, festooned with Christmas decorations, where the civilians hissed and booed them and the children threw snowballs.

Once they made the tough climb to the hilltop camp, one 106th Division soldier recalled that during the in-processing, “Some men refused to give anything more than their names, ranks, and serial numbers. The German officer got mad and called two guards over. The guards hit the Americans with their rifle butts and made them stand outside in the snow for three or four hours. I saw this happen to 20 or 25 men.” Many of those so treated came down with frostbite.

The GIs were then assigned to barracks that were pestilential at best. Each of the lice-ridden barracks held about 500 men but had no bathroom facilities and wholly inadequate stoves for heat. Some barracks even lacked bunks, so many POWs were forced to sleep on the cold, hard, concrete floors.

To keep the POWs busy, the Germans assigned them to work details, such as cutting wood in the surrounding forest. The quantity and quality of food could not keep up with the GIs’ physical exertion, so the POWs began to lose weight at an alarming rate.

While POWs at most of the other German camps were treated humanely, the Geneva Convention’s rules about the treatment of prisoners were blatantly ignored at Stalag IX-B.

James Smith said that at Bad Orb the kitchen was run by Russian POWs. “They served us a meal of carrots and all kinds of mixed vegetables—beets and carrots and cabbage and grass. I thought: ‘That’s the worst meal I’ve ever had.’ Later on, I found out that it was the best meal I was ever offered there . . . At night we’d get a small loaf of black bread mixed with sawdust that had to be divided among eight prisoners.”

During the day, before, after, and during work details, the German guards abused their prisoners verbally and physically, often beating them for small infractions of camp rules. And with basic sanitation lacking (the POWs weren’t even allowed to bathe or change clothes), dysentery, diarrhea, and typhus were rampant.

The POWs did not learn for quite some time that the Battle of the Bulge in which they had been taken prisoner had turned out in the Allies’ favor. After decimating the 28th, 99th, and 106th Divisions, Operation Wacht-am-Rhein fizzled out with horrendous casualties for the attackers. Germany’s last major gamble had failed.

Caught in a North Wind

The Germans’ second westward offensive, Operation Nordwind (North Wind), aimed at American forces further south in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France, also petered out—but not before more Americans were killed or captured. Pfc. Gerald Daub, a New Yorker and member of Company F, 397th Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, was one of those GIs taken prisoner.

Earlier in November 1944, he had been wounded in the head by a sniper, recuperated, and returned to duty. On December 31, the Germans attacked through the mountainous, heavily wooded area and the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division hit Daub’s unit. He said, “We had no tank support at that time and were defending a crossroads. We were so vulnerable that they were able to attack us from both the front and rear.”

During the battle, Daub and another soldier, Howard Hunter, wound up in a house surrounded by the enemy. Facing imminent death, Hunter suggested to Daub that they surrender. “Not me, Howard,” Daub said. “I’m Jewish.” A grenade thrown into the house convinced the pair to give up; they were quickly taken into custody.

A short distance away, Leon Horowitz, a member of Daub’s company, was also taken prisoner. “When I was captured,” he said, “one of my soldier mates advised me to throw away my dog tags, which I did. In those days, your religion was imprinted on your dog tags so that, if you were killed, they would know what kind of burial service to give you. Catholics had a ‘C,’ Protestants had a ‘P,’ and Jews had an ‘H’ for Hebrew. In retrospect, I’m sure the Germans would have quickly suspected that anyone who didn’t have dog tags was Jewish.”

Also being taken prisoner during the Nordwind counteroffensive was Norman Fellman, a New Yorker with Company B, 275th Regiment, 70th Infantry Division. Fellman said that his unit, nearly out of ammunition, had no choice but to surrender.

“We were marched to a railhead,” he said. “My first encounter with a rifle butt was while going past a bridge abutment; there was an icicle hanging from it. I was dry and thirsty, so I stepped out of line and grabbed the icicle and got my first introduction to the fact that we weren’t free to do what we pleased anymore.”

After riding in boxcars after several days’ march, Fellman recalled that his train was strafed by Allied planes and there were some casualties. After about a week’s journey in the boxcars, the train finally arrived at Bad Orb. The prisoners were marched up to Stalag IX-B to join the men captured during the Bulge.

During the in-processing, prisoners were asked what religion they were. Morton Brooks, from Brooklyn and a member of 42nd Infantry Division that had been caught up in the fighting in Alsace-Lorraine, said, “I wasn’t going to hide the fact that I was Jewish, so I told them.” He had no idea what was in store for those who identified themselves as Jewish.

Conditions were so bad at Bad Orb that, one night, a pair of starving inmates broke into the camp’s kitchen to find food. A guard tried to stop them but the two GIs attacked him with an ax. Norman Fellman recalled that the camp administration was furious about the incident and ordered all the prisoners out of their barracks to spend hours standing shoeless and coatless in the snow-covered roll-call square.

The camp commandant had machine guns set up and threatened that groups of 10 inmates would be shot unless and until the two culprits came forward. Once the two offenders were identified, the rest of the prison population was allowed back into their barracks.

Life, work, and punishment went on at Bad Orb for the next few weeks until, on January 18, 1945, the prisoners were assembled and told that all Jewish soldiers were to identify themselves.

Leon Horowitz recalled, “We didn’t know what that order meant. We had heard a little bit about the Nazi extermination of the Jews in Europe, but we couldn’t conceive that this would be carried out against American soldiers.”

That evening, discussions in the barracks raged about whether or not the Jewish soldiers should comply. Some argued that the Germans might kill everyone if the Jews didn’t come forward. Others said that the Germans would never dare harm Americans no matter what their religion was.

The inmates elected Hans Kasten to be their “Man of Confidence”—a soldier selected by the prisoners to be their spokesman or liaison with the German camp administration. Kasten and the other barracks leaders met with the commandant and were told again that all Jewish POWs must identify themselves the next morning.

When the order was given at roll call, most of the Jews stepped forward. The 80 to 100 Jewish GIs were told to gather their belongings and then were marched to a separate section of the camp—“a kind of ghetto within Stalag IX-B,” recalled Horowitz. “We had to go out and chop down trees for firewood, most of which the Germans took for their own barracks. And we had harsher work details.”

On the Move Again

The Jewish prisoners were not in their new home for very long. In early February, the commandant of Stalag IX-B received orders to ship 350 POWs by rail to a labor camp at Berga-an-der-Elster, a small town near the Czech border 125 miles east of Bad Orb.

The commandant selected the 100 Jewish prisoners as part of this shipment, along with another 250 non-Jewish POWs who had been singled out as “undesirable” or “troublemakers.” Hans Kasten was part of this group.

Norman Fellman said that the Germans, in order to make the 350 quota, selected others who “looked Jewish or had Jewish-sounding names.” Luckily, Leon Horowitz had fallen ill from pneumonia and was excluded from making this journey.

On February 9, the 350 selectees were marched down the hill from Stalag IX-B to the train station where a line of boxcars awaited them. Gerald Daub recalled that the conditions inside the boxcars on this trip were as bad as on their previous rail journey to Bad Orb, with a bucket in the corner their only toilet.

In the four or five days that the trip took, the POWs had been given only a slice of bread and a drink of water at the start of the journey, and were subjected to strafing runs by Allied warplanes along the way. In each boxcar, which held from 60 to 80 men, some died, mostly by being crushed to death.

The train wound its way eastward, coming close to the Buchenwald concentration camp outside of Weimar, and on February 13 finally stopped at the small town of Berga on the Elster River.

The gaunt, weary, bleary-eyed POWs climbed down from their foul-smelling railcars and into the noise of shouting guards and barking dogs. As they were marched away from the train station, the prisoners saw a thousand terribly thin men in blue-and-gray striped uniforms staring back at them from a barbed-wire enclosure known as Berga One. These individuals had been brought from Buchenwald to work on constructing an underground factory in the mountains surrounding Berga.

Norman Fellman was haunted by the faces as he walked by. “Their eyes were the most dominating feature,” he said, “just watching us in total silence. I will never forget it—the saddest eyes I’ve ever seen in my life.”

The Americans continued marching southward out of town, toward the hamlet of Eula. The road steepened until, after about a kilometer, the group reached a small barbed-wire fence enclosing four or five wooden barracks—a hilltop camp unofficially called Berga Two. This would be their new home.

At first, the new camp seemed to be a vast improvement over their barracks at Bad Orb. Peter Iosso, one of the non-Jews selected to make the trip, said, “Triple-decker beds and bedding, new eating utensils, an outdoor sheltered latrine, a tank of water for personal hygiene and laundry, tea in the morning, a thick potato soup at noon.”

But overcrowding quickly became a problem—350 men stuffed into five buildings. William Shapiro added, “None of us had the slightest clue as to what was in store for us.”

The POWs were to be turned into slave laborers working in conjunction with the 1,000 inmates from Buchenwald to dig a series of mine shafts or tunnels in the Steinberg mountain on the bank of the Elster River.

None of the prisoners knew at the time why the tunnels were being dug. Some thought the tunnels were to be used as bomb-proof underground manufacturing facilities for various types of armaments. It was rumored that the Germans were building their aircraft in such in-mountain factories.

As it turned out, the 17 huge tunnels being excavated under the Steinberg were to be used as oil-shale production facilities to provide petroleum for the German war machine because most of its oil supplies were cut off by the Allies. The project at Berga was code-named “SS-Command Swallow Five.” Work went on around the clock; the Buchenwald inmates would work a 12-hour shift and the American POWs would work the next 12-hour shift.

Working in Hell

On the first day the Americans were marched to the work site, Berga’s “hostile residents spit on us as we walked through the town,” Peter Iosso recalled. Once they got to the tunnels, the Buchenwald prisoners were just getting off work. Gerald Daub said that the gangs of political prisoners “looked like they were starving and dying, which they were. They were falling and being beaten by their own foremen to get up. Rocks were being drilled and explosions were going off, dust flying everywhere. It was my impression of Dante’s Inferno, like my vision of hell—a totally hellish place.”

Daub was picked to drill holes in the rock face of the tunnel. “I’m not a tremendously big guy. The drill was very big; it had a bit that was six feet long. The thing would vibrate; I could feel myself vibrating even after I was done drilling.

“We got back to the barracks and complained about it to Hans Kasten, our ‘Man of Confidence,’ who then complained to the commandant. We threatened that we would not go to work the next day, that we would go on strike.”

Peter Iosso remembered that the strike threat did not go very far. “The next day when they came to take us to work, we refused and protested that the work violated the Geneva Conventions. The German guards entered the barracks with bayonetted rifles and rousted us out, kicking and hitting many with the butts of their rifles—the first of many occasions that they did this to make us move faster.”

Daub added that the guards had vicious German Shepherds and threatened that they would turn the dogs loose if the POWs didn’t get out and get to work. “So we all got out and marched off to work and really didn’t give them any trouble after that,” he said.

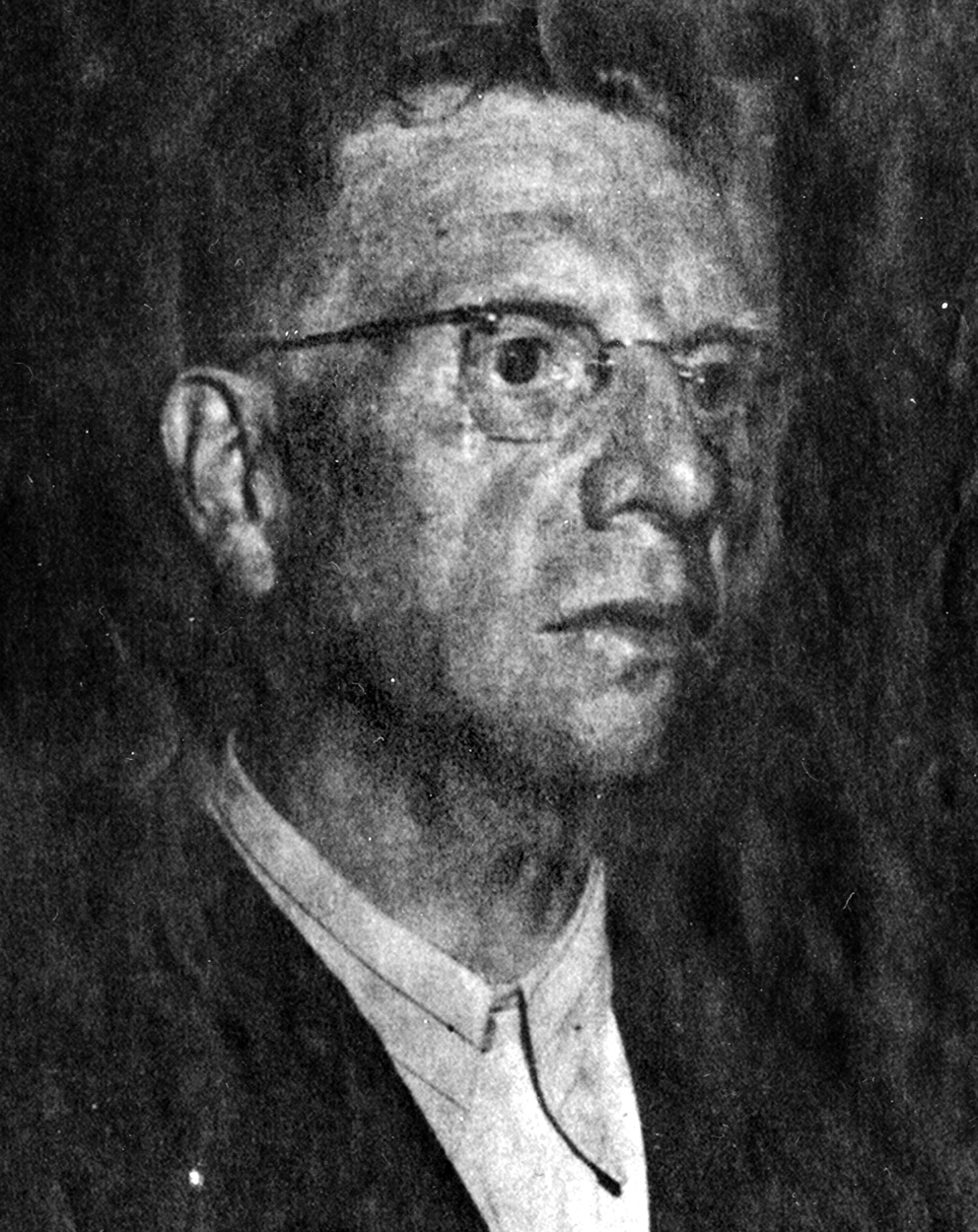

In early March, three prisoners, including the Man of Confidence Hans Kasten escaped. Because of this, the camp foreman was sacked and in his place came a brutal, sadistic World War I veteran named Erwin Metz.

Metz, 52, was a former bank clerk and a sergeant in Home Guard Battalion 621 that was in charge of the slave labor force at Berga. William Shapiro recalled that Metz “had a distinctive voice that sounded like Donald Duck.” But the sergeant was no cartoon character.

“Unquestionably,” Shapiro continued, “in Berga and on the ‘death march’ later, Metz’s cruel, indifferent, oppressive, and deliberate actions caused the deaths of many of the POWs and added to our indescribable sufferings. We were the Untermensch—slaves, undesirable humans with whom he could do as he pleased without regard to any sense of humanity.”

Shapiro related seeing many of the political prisoners in Berga One being lynched on Metz’s orders: “I felt frightened, lost, defenseless, and intimidated. I looked away … I did not want any of the SS troopers to notice my observation of the hangings.”

Norman Fellman remembered the terrible working conditions in the tunnels: “We would drill holes in the rock walls of the tunnel with these big, pneumatic drills. We would drill 15 or 20 holes at a time. Some of our people made gunpowder ‘sausages’—cloth bags filled with gunpowder—and would stuff 18 or 20 of those in the holes, and then they would run fuses to all of the holes.

“We would get out of the tunnel and they would blast. Before the dust had settled, before the noise had stopped echoing, we were forced back into the tunnels. Nobody had protective gear of any kind. You’d breathe that air, you’d breathe that [crap.]”

Gerald Daub recalled, “The air was just totally filled with stone dust. Everything was coated with it, including your lungs that were filled with it. And we had no bathing facilities; after a day or two we looked like cement statues walking around.”

The rock blasted from the tunnels was then shoveled by the slave workers into mining cars and dumped into the Elster River.

Returning to Berga Two after a dirty, exhausting day of working in the tunnels brought no respite. “We had to stand in the cold, freezing weather for hours while the guards counted us over and over,” William Shapiro said. “Finally, the rations of a bowl of rotted potato or turnip-top green soup and a slice of hard, grainy, black bread was the meager ‘reward.’”

Peter Iosso remembered, “We tried to make that tiny piece of bread last as long as possible.”

Even the barracks brought no relief. Tony Acevedo, a Mexican-American from California, recalled, “White lice—oh, my God! I’ll never forget it. I can still feel them running up my back.”

Most escape attempts failed, and the escapees who were brought back were subjected to severe abuse by the guards. Sergeant Metz frequently did the beatings himself.

Joseph Mark and two other prisoners hatched an escape plan that almost worked. Slipping away from their work detail, the trio stopped at a farmhouse to steal potatoes and milk a cow. But they were captured by civilians after three days and turned over to the authorities; they were soon back in Berga.

It didn’t take long for the POWs to begin dying. Causes ranged from starvation, ulcerated wounds, pneumonia, beatings, work-site accidents, suicide, and more. Medic William Shapiro said, “Impending death was all around me.”

The only way the POWs could fight back was by small acts of sabotage at work. Loading the mining gondolas incorrectly could cause them to tip over and fall into the river. Other inmates mixed dirt with the explosives, so the charges would fail to detonate properly. Of course, beatings with rifle butts and rubber hoses followed.

Beginning of the End

The POWs had had no news of how the war was progressing. The Germans might have won the Battle of the Bulge, for all they knew, and might even have won the war. But the sight of increasing overflights of Allied planes, and the sounds of bombs detonating not far away, gave them hope that perhaps the Allies were heading their way.

Norman Fellman noted, “Sometimes it would take about 45 minutes to an hour for the planes to go over because there were so many of them, and the sound always made us feel good.”

Spring slowly arrived but the brutal work and punishments never ceased. Near the end of March the Americans suddenly found themselves working in a forest instead of the dust-filled tunnels. Joseph Mark said, “The change from the dark tunnels to the light of the forest was like an elixir for us, a reprieve. The sights and sounds of the trees and birds brought back memories of a more familiar and friendlier world we had known.”

On April 2, 1945, American forces reached Stalag IX-B, the mountaintop camp at Bad Orb. The POWs still there were unexpectedly left unguarded. A few German soldiers remained to try and halt the American advance but they were soon swept aside, and the liberators were shocked to find the sick, emaciated American prisoners in a state of near-starvation. Unfortunately, the generous distribution of rich food to the emaciated men killed some and brought others to the brink of death.

Over the next few days the freed POWs at Bad Orb were washed, deloused, carefully fed, and brought back to a reasonable state of health.

Unknown to the liberators, throughout Germany and the Nazi-occupied territories, the concentration camps were being emptied, the prisoners being sent under armed guard on a march to nowhere, a march to oblivion. SS boss Heinrich Himmler had ordered the camps evacuated in hopes of keeping evidence of war crimes from the advancing Allies. Those incapable of keeping up the pace were shot and their bodies either buried in ditches or left by the side of the road.

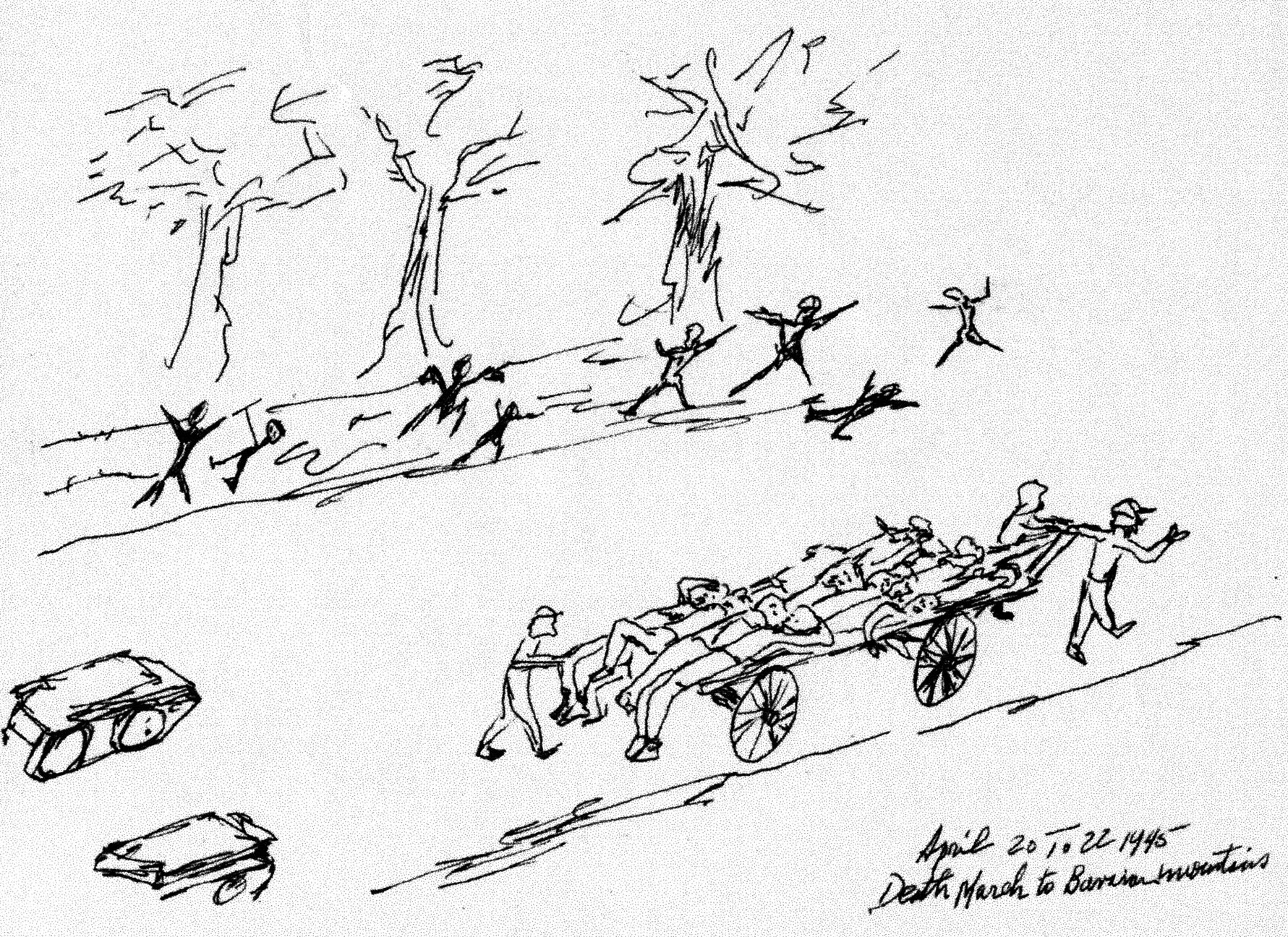

On April 3, the doors to their barracks at Berga were flung opened and the prisoners were rousted out for what they thought was just another miserable work day filled with hard labor and brutal treatment. But, after roll call, the men were marched, not toward the tunnels, but south through Bavaria, away from Berga.

Gerald Daub recalled, “We had no idea that the American Army was getting close to us until the Germans marched us out, and then we felt that we were probably marched out of camp, not to save our lives, but just to get us out of camp because the Americans were getting close. The Army entered Berga a few days after we left.”

For days the march went on—past farm fields, through forests and towns and villages, up hills and down. A farm wagon was found and the POWs unable to walk were piled onto it; the ones on the bottom of the pile suffocated to death.

Occasionally a sympathetic farmer would surreptitiously slip a bit of food to the marchers when the guards weren’t watching.

As if the work in the tunnels and the starvation rations weren’t enough, the march to nowhere took its toll. Unable to put one foot in front of the other, some POWs collapsed and were either left to die in a ditch or were shot by their guards.

The marchers also encountered other scenes of horror. Marching prisoners from other camps had used these same back roads and often the bodies of other marchers in striped uniforms were encountered, their heads blown apart by their guards.

Norman Fellman was lucky. The group he was in became strung out and fell behind and was rescued by a unit of the 90th Infantry Division that was coming up the road. “We were about as close to being skeletons as we could be and not be one,” he said.

The rest of the Berga Americans kept marching, their guards trying to stay ahead of those who would liberate them. At night the group was herded into barns, while the sickest of the POWs were taken to nearby hospitals. A few of the prisoners were able to escape while the guards’ backs were turned but most were caught and returned to the marching group.

The march went on until, on April 20, Sergeant Metz and the Berga guards were replaced by a new set of guards, who seemed a bit kinder—or at least less brutal. At a rural village named Rötz, north of Cham, the exodus came to a halt, and the POWs were ordered into a large barn.

Everyone had reached their limit of endurance; their three-week, 400-mile death march had taken everything out of them; some welcomed death. Joseph Mark said that when they reached the barn at Rötz, “We just fell into a slush of cow urine. At that point, you just didn’t care. You just wanted to die.”

Liberation at Last

The next morning, April 23, when their guards ordered them up and out of the barn, the POWs, beyond exhaustion, just laid there. A few minutes later, tank engines and shots were heard outside and the guards suddenly vanished.

One of the prisoners looked out of the barn. Morton Brooks said, “He saw tanks coming up the road, and some of our fellows shouted, ‘Americans!’”

It was the 11th Armored Division coming to the rescue.

The 11th had already discovered and liberated over 3,000 American and Russian POWs they found wandering the roads of Bavaria by the time they got to the barn at Rötz, so they were well-versed in what to do. They had also seen ghastly evidence of Nazi atrocities perpetrated on the death marchers.

William Shapiro remembered being faintly aware of the sounds of approaching tanks. “I believe that I was in that twilight zone before death that I had observed in some men in Berga. I do not believe that I was sick with any disease except severe weight loss, intermittent diarrhea, exhaustion, and lice infestation,” he said.

But then he saw a Sherman tank with a white star outside the barn. “And then some men started to shout and scream that they are Americans.” It slowly came over him that he was liberated, saved.

Medical personnel began ministering to the 160 survivors of the approximately 280 who had started out from Berga three weeks earlier, working hard to bring each man back from certain death.

Two days later, an Army officer from the Military Intelligence Service came around with forms and said each man had to sign a “security certificate” before they could be discharged from the Army.

The certificate required that ex-POWs promised never divulge what had happened to them during their captivity. The reasons for such a requirement remain unclear to this day.

Over the next few months, once the ex-prisoners had spent time in hospitals regaining their strength and being treated for their various ailments, they were transported back to the U.S. in ships and planes.

Each man had a heart-rending reunion with mothers, fathers, wives, and girlfriends, and remembered their return as the happiest day of their lives.

William Shapiro’s homecoming in mid-June was typical. He flew in to Mitchel Field in Hempstead, Long Island, and scrounged a dime to call his brother David in Forest Hills, Queens, New York. His brother, wife, parents, and girlfriend Betty drove out to greet him.

“I was waiting at the front gate,” Shapiro remembered. “I had a new uniform on. I was no longer emaciated but I was not up to my normal weight as yet. I began to run toward them as I sighted them walking through the gate. There was a lot of hugging and kissing. I remember sitting in the back seat of Dave’s car; Betty and I were holding hands and I was looking out the window, viewing the highway, going to the Bronx, and I truly could not believe that the ordeal was over, that I was going home.”

Epilogue

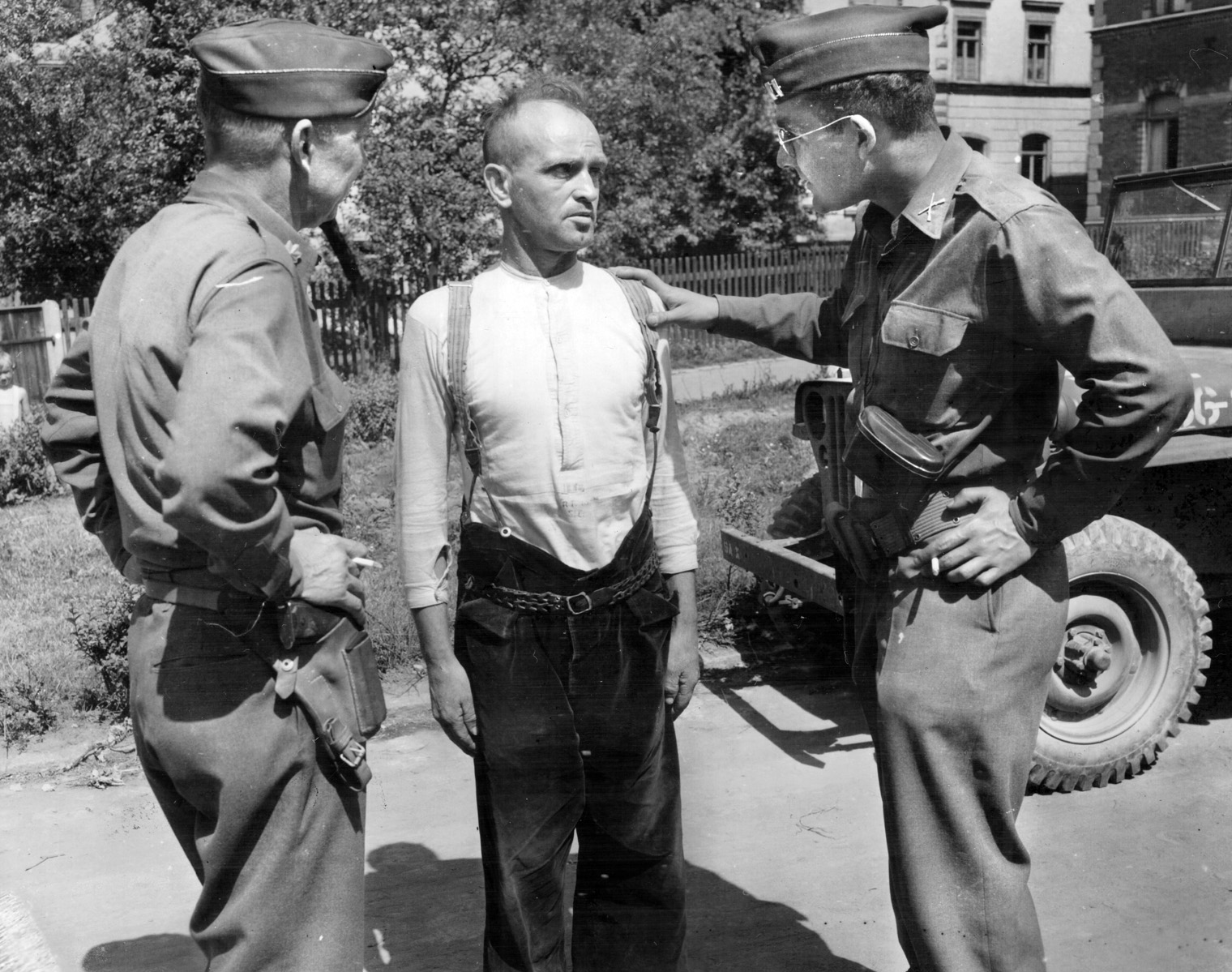

In 1945, war-crimes trials of the guards and administrators of the POW camps began. Sergeant Erwin Metz, along with his superior at Berga, a Captain Ludwig Merz, claimed that they had done everything within their power to make life at the camp as comfortable as possible. Metz even claimed that on the “death march” he would peddle ahead on his bicycle to obtain food for the marchers.

Despite the fact that no former Berga prisoners were called to testify (or even knew about the existence of the trial), both Germans were found guilty on October 15, 1945, and sentenced to death by hanging.

In 1948, petitions for clemency were presented to the War Crimes Review Board. The board reduced Captain Merz’s death sentence to 20 years in prison and Sergeant Metz’s to five years. Neither man served his full sentence and both were released from prison to resume their lives—something over 100 Americans who had been incarcerated at Berga were unable to do.

This article is adapted from the author’s book, Given Up for Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga (Hachette Book Group, 2005).

I never understood why they did not let these men share their stories and did not have them testify in the cases against the perpetrators of these horrible acts. Then without all of the testimony they commute the sentence from death to 20 years to 7 years. Was it with time the horror was less to those in charge?