by Kathleen Karr

CONFIDENTIAL TO LEADERS

It is a well-known fact, of course, that any movement needs something to dramatize it, to appeal to the public’s sense of sensationalism. Something to talk about, and to wonder about …. The fiery swastika, burned between the hours of 9 in the evening and 11 at night, will give our movement that which it must have—publicity … The press should be tipped off, if possible, in advance or immediately after the swastika is set afire. The idea is to have as many pictures of it as possible broadcast throughout the Nation.

Pro Patria,

AMERICAN NATIONALIST CONFEDERATION

Burning swastikas in America? Yes, it did happen here. Storm troopers practiced their marksmanship under the welcoming umbrella of the National Guard. Nazi spies plied their trade in the shipyards of New York City. Hollywood yelled foul with anti-German movies. And J. Edgar Hoover turned a deaf ear to it all. If this sounds like an alternate interpretation of history, read on.

The Great Depression was a tremendous breeding ground for dissension in the United States. Malcontents, home-grown bigots, and small-time racketeers jumped on the bandwagon to cash in their ideas for money, power, notoriety, or all three. During a period when many working men were unemployed and feeling dispossessed from the American Dream, these dissenters found their target market willing to follow any variety of new leader who would promise to get them on their feet with any political philosophy faster than Franklin D. Roosevelt could.

Unseen Threats to American Ideals?

There were, of course, the classic opposition leaders: the ill-fated Huey Long of Louisiana; Dr. Francis E. Townsend with his “Townsend Plan,” a social security program for the elderly; and Father Charles E. Coughlin, the right-wing radio orator and publisher of Social Justice. As frightening as some of the policies of Long and Coughlin seem today, it was the hidden dissenters who were ultimately capable of performing a larger scale of sabotage on the American ideals of liberty and equality.

In 1938, the Dies House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) accounted for at least 135 so-called “unAmerican Organizations.” A large number of these took as their inspiration the Ku Klux Klan—not in name, but in spirit and organizational structure. To this was added the worst tenets of Hitler’s National Socialism: anti-Semitism, because a concrete scapegoat was necessary; and the massing of trained civilian armies, because someone had to enforce the bigotry and be prepared for the coming coup.

With the well-organized German-American Bund offering appropriate guidance and propaganda material, the race was soon on between competing führers and organizations. There were the Knights of the White Camellia and the Silver Legion of America (the Silver Shirts), among scores of others, but the Bund was most capable of long-term mischief.

The German-American Bund began in 1924 as the Teutonia Society, a group of German-speaking Chicagoans. Out of this grew the League of the Friends of New Germany in 1933, and in 1936 the League changed its name to the German-American Volksbund, or Bund.

By 1937, the Bund was divided into three departments: the East (New York), the Middle West (Chicago), and the West (Los Angeles). The leader of each department was a member of the national staff headed by Fritz Kuhn. At the time, the 50 local units of the Bund had an estimated membership of around 20,000. Exact numbers are impossible to obtain, as Kuhn personally ordered the destruction of all membership lists when it was rumored that the Bund was about to be investigated by HUAC. Such secrecy made sense. Should the United States go to war with Germany, German members could be watched, even interned, but Americans not known as Bund members could continue to move about freely.

Buy Gentile! Employ Gentile! Vote Gentile!

The Bund sponsored newspapers in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Appearing under the subtitle, “The Free American,” Der Deutsche Weckruf und Beobachtercarried news of general interest to the German population, true, but it also strongly supported Hitler’s National Socialist regime and all it implied. The paper ran notices of upcoming shortwave broadcasts from Germany under a column called “Tune in Berlin,” along with notices of Bund meetings and lectures. More importantly, the paper had intimate knowledge of what was going to happen in Berlin. The Bund announced celebrations to commemorate the joining of Sudetenland to Germany days before the area was occupied.

Offshoots of the Bund included the German-American Settlement League, which sponsored youth camps, and Deutscher Konsum Verband, Inc., better known as the D.K.V., or German-American Business League. The D.K.V. supposedly existed to fight the anti-Nazi boycott, but in reality promoted an anti-Jewish boycott. Through the distribution of propaganda leaflets (“Buy Gentile! Employ Gentile! Vote Gentile!”) and a trading-stamp program, the D.K.V. tried to persuade Bund members and sympathizers to purchase only from stores owned by fellow members.

Another offshoot of the Bund was the Ordnungs Dienst,or O.D., a uniformed group modeled after Hitler’s storm troopers. According to an FBI report, the purpose of the O.D. was “to fight Bolshevist and Marxist movements. To take part in the parades, to make arrangements for the various meetings, prepare decorations, serve as ushers, carry flags and protect meetings of the Bund from assaults of Communists.”

The reality was different. Members wore uniforms almost identical to their German counterparts and met for German-style drills each week. The O.D. denied having any involvement with firearms, and the 1937 FBI report concurred. However, the need to become familiar with such equipment was easily satisfied through strategies such as setting up target ranges for weekend sporting purposes at Bund camps, hiding rifle ranges on outlying farms, and more significantly, having Bund members join their local National Guard. The latter system worked so well that at one point an entire company of the Illinois National Guard consisted of Bund members.

O.D. members were also given the opportunity to visit Germany free of charge by being shipped on German liners as sailors. During these visits it was recommended that they attend six- to eight-week propaganda courses before returning to the United States. This was exhilarating stuff for the common working man, and by the fall of 1938 over 5,000 German-Americans had succumbed to the lure of the Bund’s storm troopers.

The O.D. often used strong-arm tactics in subduing dissenting audience members at Bund meetings. They also “taught lessons” to Jewish-Americans in off-hours. But most sinister was the deliberate pitch made for the minds of the young through the ODeutsche-Jungenschaft,or German-American Youth League.

Established in 1934, this youth movement was divided into three sections: the Jungenschaft (boys), the Maedchenschaft (girls), and the Jungvolk (children from five years old). Theodor Dinkelacker, the national youth leader, had this to say about his charges during his HUAC testimony: “Youth bunds are proud of being the future of the only fighting organization in German-America…. All boys and girls have the obligation to keep themselves strong and healthy for their German race; healthy in order to transmit as a link in an unending chain in the heritage of our ancestors to the coming generation; strong in order to ward off every attack against the German race; politically and economically.”

“You Are Not Supposed to Show Any Sympathy”

The Bund addressed this obligation by developing summer camps across the country where young German-Americans could be schooled and drilled in German language, history, and customs. Although camp life was strictly regimented, it appealed to the youngsters’ natural taste for the dramatic. Camps with exotic names like Camp Siegfried or Will and Might made use of campfire-song sessions, night marches, and the distribution of coveted German-issue hunting knives called “Honor Daggers.” Each Honor Dagger bore the inscription Blut und Ehre (Blood and Honor) on its blade and a swastika on its hilt. Saturday German schools and weeknight meetings also were held throughout the year to reinforce the ideals of the Bund.

The most interesting firsthand account of life within these youth groups and camps was furnished to the Dies Committee by a disgruntled former member, 19-year-old Brooklynite Helen Vooros. Miss Vooros readily documented her experiences, from the first frustration of having to pay $11 for a regulation uniform to the realization of the seriousness of the youth leaders, and then to digust at their immoral behavior. Political discussions were required, and homework and tests included the works of both Adolf Hitler and Julius Streicher, Hitler’s fanatical anti-Semite propagandist. She complained of her embarrassment on being fined in pennies each time she lapsed into English, or worse still, being forbidden to wear the uniform. Most fascinating were Miss Vooros’s insights into the stoical philosophy behind youth camp night marches: “If we are on a march, the more scratches we have, the better it is. It is better to have them, because we show that we can take it…. You are supposed to be without feeling about it [pain]. You are supposed to be without feeling of pity. You are not supposed to show any sympathy.”

The final indignity for Miss Vooros was the laissez-faire attitude adopted toward moral standards. She said of the American camp she attended: “[The leaders] saw the boys and girls there together, doing things that they should not be doing. That was brought up with the youth leader [of the camp] at that time, Mr. Vandenberg, and there was a discussion about what should be done about it. Later he called a meeting, and said that the boys and girls should go somewhere where people did not see them, and should hide it better … that they should follow their instincts. That appalled me to know it was going on, and there was a lecturer at the camp there who said this was pure and noble, and they should not curb their instincts, and a girl should not feel ashamed if she had an illegitimate child; because, in Germany, they have what they call mutter-kind heim [mother and girl homes] where a girl could go with her child and they would receive a home and shelter there. And they said, they have to know that we women, we girls, when we grow up, that our duty was to have children; that we should produce; that was all we were there for, and that the German population in this country should grow.”

22 Camps Within 20 Miles of Army Bases

Miss Vooros detailed how the most promising teenagers were offered trips to Germany, from the voyage on German ships where they were taken under the wing of the boat’s political officer, to the stay in Germany itself which included several months at propaganda camps. The brightest teenagers were offered longer stays of up to eight months. During this period useful skills such as learning to transmit and receive shortwave radio signals were taught.

Helen Vooros’s testimony was ignored, and by the summer of 1939 there were 22 Bund camps functioning, each one located within a 20-mile radius of an important Army base or munitions plant.

The man responsible for the youth camps, the O.D., and all these other activities was Fritz Kuhn, the führer of the German-American Bund.

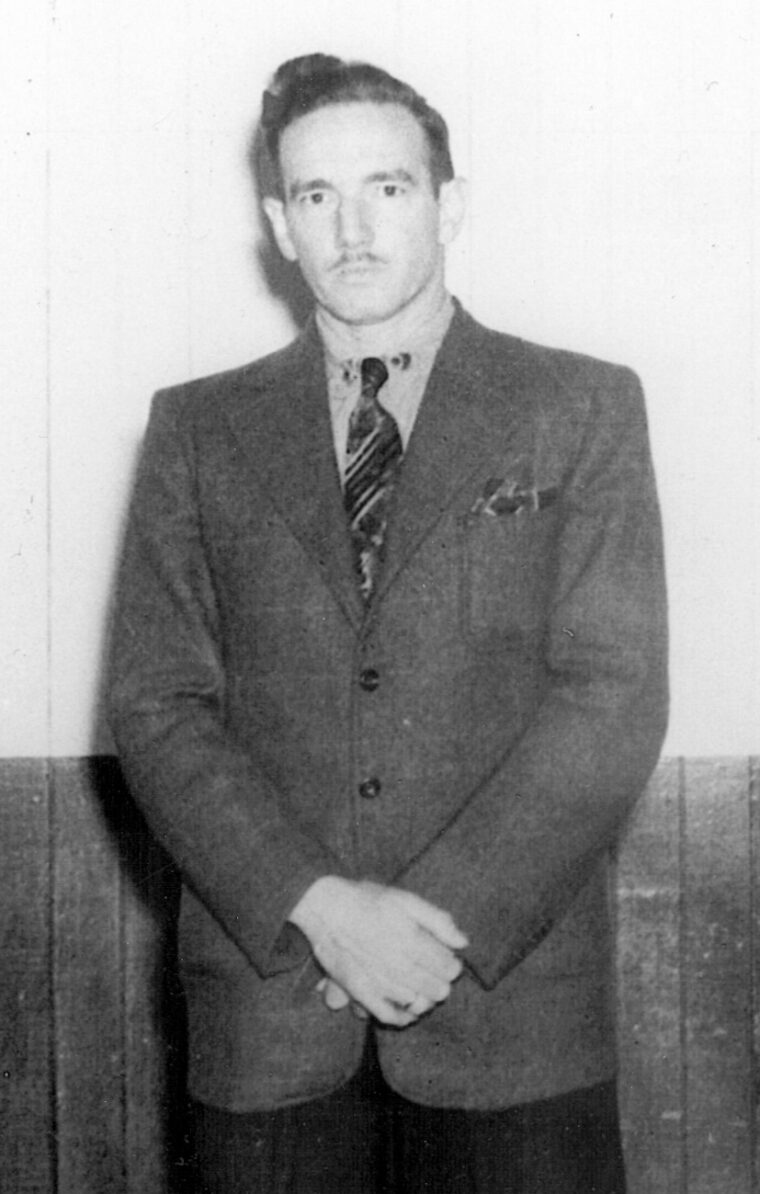

Born in Munich in 1896, Kuhn served in World War I, joined the Nazi Party in 1921, and allegedly participated in Hitler’s famous Munich Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923. After emigrating to Mexico with his wife in 1924, he entered the United States in 1928 with his family (two children were born in Mexico) and was granted U.S. citizenship in 1934. Kuhn lived in Detroit until 1936, employed as a chemist by the Ford Motor Company. During this period he became the local leader, then the Midwest leader of the Friends of New Germany. When Kuhn moved to New York in 1936, he took on the full-time position as head of the newly named Bund, which was created at a convention that he had organized.

Police Struggle to Keep 100,000 Protesters at Bay

A stocky man with a heavy German accent, Kuhn saw himself as an American Hitler and strongly modeled himself on that pattern, from his dictatorial approach to his underlings to his speech-making style. In fact, Kuhn had met Hitler on several occasions and even went so far as to duplicate some of the Teutonic excesses of Hitler’s mass rallies at the George Washington’s Birthday Rally held by the Bund at Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939. This mass demonstration of fascist strength was attended by 19,000 of the faithful. It was protected by 1,500 New York City policemen called in to keep the 100,000 protestors surrounding the Garden from storming it.

On a personal level, Kuhn was domineering, arrogant, and a petty chiseler. Generally disliked by all but his immediate subordinates, he had two serious weaknesses: women and high living. Kuhn was apparently fired from his position at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit for an affair with an employee. Undaunted by that incident or by the fact that his wife was considering divorce, Kuhn continued his flirtations in New York, secure under the umbrella of his new position. Walter Winchell, who carried on a long vendetta against Kuhn and the Bund from his On Broadway syndicated column, listed sightings of Kuhn at the Stork Club and demanded that the authorities ascertain the source of Fritz Kuhn’s funds. Winchell was not the only one interested in Kuhn’s finances. According to his own testimony, Kuhn earned $300 a month from his various enterprises. But he was spending much more on nights on the town.

Police Surprised and Arrested Kuhn

Small wonder that Kuhn was finally investigated and brought to trial, not for his political convictions, or because of his paramilitary organization, but on charges of stealing $14,548 of the Bund’s funds. He was indicted by the New York County Grand Jury on May 25, 1939. After a mad dash for freedom along a well-planned route to pick up accomplices and traveling gear, Kuhn was arrested at a small gas station in Pennsylvania Dutch country near Allentown and returned to New York.

Free on $5,000 bail, Kuhn spent the next several months mounting a campaign against his accusers, testifying for the Dies Committee, getting arrested several times for drunk driving, and carrying on business as usual. When it was rumored that he planned to flee again, Kuhn was slapped back in jail and his bail raised to $50,000. Released once more after a massive Bund money-raising campaign, Kuhn went on trial on October 30, 1939. On November 5, he was found guilty and sentenced to two-and-a-half to five years in Sing Sing, as a common forger and thief.

Denied parole in June 1941, on grounds that he was a hazard to public peace and security, Kuhn was finally released, his citizenship was revoked, and he was deported to Germany. After Germany’s defeat, Kuhn was convicted as a major Nazi offender and served two years of a 10-year sentence before being released. He died in Munich, Germany, in December 1951, at the age of 55, unnoted and unmourned. Before his fall, however, Fritz Kuhn became a background figure in the phenomenon known as the Nazi Spy Trial.

With the exception of the McCormack Hearing in 1934, and the publicized but curiously ineffective Dies Committee Hearings in 1938, the appropriate U.S. government agencies seemed reticent to investigate the Bund or any other potential Nazi spy activities. It took another syndicated columnist and an observant President Franklin D. Roosevelt to start the wheels turning in that direction. In March 1937, Heywood Broun, in his column It Seems to Me,complained about the problems of Nazi propaganda in New York City’s Yorkville, and pointed out that actual recruiting was going on in America for storm troopers loyal to Hitler.

Hoover Conceded to Investigate Bund’s Potentially Subversive Acts

President Roosevelt enclosed Broun’s column in a confidential memo to the Secretary of War with the suggestion, “I think G-2 ought to make a definite check on this statement by Heywood Broun which I have marked in the margin of this clipping.” The Secretary of War bucked the problem to the Department of Justice, which was equally reticent to attack the subject. Attorney General Homer S. Cummings threw it in the lap of J. Edgar Hoover of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, suggesting a quiet preliminary survey of the problem.

Hoover replied by private memo in due time. “I desire to point out that the Bureau does not have any confidential informants available from whom information in this type of investigation might be obtained, since the Bureau does not ordinarily conduct such inquiries … and it is to be noted that as soon as the fact that such an investigation is being conducted appears in the newspapers, the right of the Bureau to conduct these investigations will be challenged by some pro-Nazi organization. I frankly do not believe this investigation can be conducted without publicity arising therefrom.”

A quiet war of memoranda continued for some time until Hoover ultimately conceded and began an investigation of the German-American Bund and its potentially subversive activities. The FBI report, completed late in 1937 and delivered to the Attorney General’s office in January 1938, was a straight, factual report that glossed over potential civil disturbances or espionage possibilities that could arise from the Bund’s activities. In effect, it gave the Bund a clean bill of health.

But in February 1938, FBI agents in New York City stumbled into a case they were hardly prepared for: credible evidence of a network of Nazi spies working in America.

Handed to the FBI on a platter was an incredible story which began with British Intelligence’s uncovering of a Nazi mail-relay station in Scotland manned by the middle-aged widow of a German, Mrs. Jessie Jordan. Among the letters confiscated were several dealing with U.S. espionage, signed “Crown.” They were sent to military intelligence in New York and subsequently turned over to the FBI. These letters revealed that the Nazi government, anxious to secure secret plans for the defense of the East Coast, intended to seize them by force. Also revealed was a plot to steal codes and maps of the U.S. Army Air Corps, as well as a convoluted scheme to forge President Roosevelt’s signature on White House stationery to secure blueprints of America’s newest aircraft carriers, the Enterprise andYorktown.

Spy Wanted: $50 a Month Plus Bonuses

Efforts to locate “Crown” were foiled until February 14, 1938, when a conspiracy to secure a large number of blank U.S. passports failed. Picked up for questioning by the Alien Squad and State Department agents before being turned over to the FBI was one Gunter Gustav Rumrich, alias “Crown.”

Rumrich was a frustrated young egotist who had personally applied for a spy job in the United States. Born in 1911 in the United States of an Austrian diplomatic family, raised and educated in Austria-Hungary, he had reentered the United States in 1929 on his status as an American citizen. After a series of menial jobs he joined the Army, deserted, served time in a military prison, reenlisted, and again deserted. When arrested in 1938, Rumrich had been reporting information of minor importance to Germany for about a year. For this he was paid $50 a month with the promise of bonuses for exceptional information.

Rumrich’s confession to the FBI ultimately implicated a confederate of his, Erich Glaser. But more importantly, it produced enough facts to interest the FBI in the activities of Dr. Ignatz T. Griebl of the German-American Bund. It outlined Griebl’s dealings with the Nazi espionage system as it was organized through the couriers and propaganda officers of German ocean liners making scheduled runs to the port of New York.

Dr. Griebl, a New York surgeon and obstetrician prominent in Yorkville, the German section of New York City, was a strong supporter and occasional speaker for the German-American Bund. Griebl was also a close friend of Fritz Kuhn and shared Kuhn’s passions for women and anti-Semitism. Griebl, however, also occasionally housed and was the go-between for a series of Nazi spies specializing in the procurement of U.S. military information.

As a friendly witness for the FBI during the spring of 1938, Griebl’s testimony was responsible for the apprehension of Johanna “Jenni” Hofmann, an attractive hairdresser on the North German Lloyd liner SS Europa.Griebl’s information was also responsible for the apprehension of two aircraft factory employees who had been supplying information to Germany—Werner George Gudenberg and Otto Hermann Voss.

During the months of follow-up investigation, the FBI inexplicably took such a low-key interest in these events that any “friendly” suspects were allowed to freely come and go at will. As a result, several went. On May 10, 1938, Griebl stowed away on the SS Bremenand steamed out of New York to pursue a medical practice in Vienna. On May 25, Gudenberg boarded another liner, the SS Hamburg, feigned illness when U.S. officials attempted to remove him from the boat in England, and ultimately disappeared from sight.

Confessions of a Nazi Spy

Consequently, on June 20, 1938, when the Federal Grand Jury in New York indicted 18 persons on charges of conspiring to steal military codes and confidential information concerning the armed forces and ships and aircraft of the United States, only four members of the spy ring were in hand for the trial. Thirteen of those indicted were in Germany, either members of the Nazi espionage system or spies who had since fled the United States. Mrs. Jessie Jordan was already serving four years in a British jail for espionage. The four remaining members of the ring, Rumrich, Jenni Hofmann, Erich Glaser, and Otto Voss were brought to trial on October 14, 1938, in the U.S. Court House in New York. Rumrich pleaded guilty and testified against the others. After a sensational trial that made daily headlines in the press, all were found guilty. Rumrich and Glaser were sentenced to two years of imprisonment, Jenni Hofmann to four, and Voss to six.

Leon G. Turrou was the FBI agent on duty that day in February 1938 when Rumrich/ Crown was first apprehended. He was placed in charge of the case, and in the course of the trial and through the lens of the press, Turrou himself became the chief object of the public’s imagination. And why not? Turrou’s background was even more exotic than Rumrich’s. Turrou was born in Poland and spent his childhood floating with foster parents between Egypt, China, Russia, Berlin, and London. By the time he arrived in the United States to make his fortune at 17, he reputedly spoke 13 languages. Turrou was wounded twice while serving with the Imperial Russian Army in World War I and worked as a translator and U.S. postal clerk before ending up in the FBI.

Turrou lost no time capitalizing on his instant fame. As soon as it was reasonably decent, he resigned from the FBI. As a star witness for the spy trials that followed, he sold the rights to his story first for serial publication in the New York Post, then in book form, and finally to Hollywood, where his experience in cracking the spy ring became the basis for the Warner Brothers film Confessions of a Nazi Spy.

Warners had closed down its German office in 1936 after its local representative, Joe Kaufman, a Jew, had been murdered by Nazi thugs in a Berlin backstreet. The Warner brothers, also Jewish, had been searching for a suitable property to use as a wakeup call to America. Alerted to the forthcoming Turrou articles, Jack L. Warner purchased the motion picture rights, and everyone waited for the trial’s resolution so that Warners’ script department could get to work on the story.

“THE PICTURE THAT WILL OPEN THE EYES OF 130,000,000 AMERICANS!”

Because of the topicality of Confessions, all involved were anxious to get it finished and before the public as soon as possible. Originally titled Spy Story and then Storm Over America, a copy of the second draft, written by Milton Krims and John Wexley—both noted for their radical sentiments—was sent by the producer, Robert Lord, to the Hays Office for approval just before Christmas, with a note attached: “It goes without saying that this script must be kept under lock and key when you are not actually reading it, because the German-American Bund, the German consul and all such forces are desperately trying to get a copy of it.”

The security was justified. Warners received dozens of threatening phone calls during this period, as well as a barrage of unsigned hate mail. When the film was finally completed in April 1939, it was previewed for the press behind locked doors.

The film at the center of all this prerelease excitement was a tight docudrama based on the style of the most popular newsreel of the period, The March of Time.Between the fictionalized exploits of Rumrich and Griebl are spoken commentaries, maps, and newsreel montages. The cast, all low-key selections with the exception of Edward G. Robinson (who played Edward Renard, the Turrou role), was committed to the message of the film. A number of them, including Francis Lederer, a Czech, were emigres from Central Europe. Robinson and several other cast members belonged to the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League.

Shortly before its release, Confessions was touted to exhibitors as “READY … For every showman who calls himself an American! It was Warners’ American Duty to Make it! It is your American Privilege to Show it!” Later, the film was advertised to the public as a picture “made behind locked doors because it is the most daringly fearless and breathlessly awaited picture ever to come out of Hollywood!” The newspaper display ads proclaimed: “THE PICTURE THAT WILL OPEN THE EYES OF 130,000,000 AMERICANS!”

Warners’ promotion department suggested that exhibitors distribute “Novelty Nazi Tickets” (only $4 per thousand) printed on one side with a caricature of Hitler with the heading: “Nazi Ticket. For all who criticize American Liberty—A Rough Trip from Civilization back to the Dark Ages,” while the flip side bore a picture of the American flag, subtitled, “The Old Glory Road.”

German’s Were Outraged by What They Saw

The film was a commercial success in most parts of the United States, grossing $45,000 in its first week at New York’s Strand Theater, a house record. It was well received abroad, too—in those locations where it was allowed to be screened.

The Germans were outraged by the picture, particularly the scene showing a spitting image of Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels giving instructions for propaganda dissemination to major American cities. Official complaints were sent to Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Naturally, Confessions of a Nazi Spy was banned in Germany and its satellite countries. It was later learned that several Polish exhibitors who had the nerve to acquire and show the film were hanged in their theaters. The film was also banned in most of Latin America, with the exception of Mexico, Panama, and Cuba, where it did record business.

Warner Brothers was satisfied enough with the returns that the company reissued several films of a similar, antifascist nature, including Boycott and The Bishop Who Walked with God. However, the power of isolationism in the United States was still strong, and within a few months Jack Warner announced that there would be “no [more] propaganda pictures from Warner Brothers.” Instead, the studio would increase its production of light comedies.

The reviews for Confessions were mixed, but interesting. The New York Times focused on the extreme portraits of some characters: “Membership in the National Socialist party cannot be restricted entirely to the ratfaced, the brute-browed, the sinister. We don’t believe Nazi propaganda Ministers let their mouths twitch evilly whenever they mention our Constitution or Bill of Rights.”

Varietyexplained what was missing: “This one is a wartime propaganda picture in flavor and essence…. The missing motivation, anti-Semitism, is the one thing not named and ticketed. To that extent its realism is sacrificed.”

Lacking Authenticity or Too Real?

Confessions was criticized, of course, by Nazi sympathizers. In its May 18, 1939, issue, the Bund’s New York Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachterdecried “this nightmarish concoction … the choicest collection of flubdub that a diseased mind could possibly pick out of the public ashcan.” It then listed credits for the film, branding one person after another as either a “Jew” or connected to the Commununist Party.

The main plot of Confessions of a Nazi Spy was based closely on the revelations of the New York Nazi Spy Trial of 1938, and its cast clearly parallels the real participants. The principal character innovation was in combining the role of Kassel/Griebl with the figure of Fritz Kuhn, thereby involving the Bund itself more closely in the film than it had been in the spy trials. For information on the Bund, the writers relied strongly on the series of articles published in the Chicago Daily News by John C. Metcalfe, reporter, Bund infiltrator, and special investigator of the Bund for the Dies Committee. This gives the scene involving a Bund meeting an authenticity that is almost frightening to watch as the Kassel/Griebl/Kuhn character assumes Kuhn’s Hitlerian stance to rant against the American way.

The parallel between this fictitious character and the real Kuhn prompted him to bring a $5 million libel suit against the picture’s producers, Leon G. Turrou, and screenwriters Krims and Wexley. The suit was dropped on October 3, 1940, well after Kuhn had been sent to prison for theft of Bund funds.

Confessions of a Nazi Spy was reissued in 1940, with a slightly new approach to its advertising. It was now promoted in a different fashion: “WILL AMERICA BELIEVE IT … Now! … THE PICTURE WITH THE PUNCH OF A BLITZKRIEG! ‘Fantastic!’ they called it a year ago! But today Norway, Holland, Belgium are bloody proof of its TRUTH!”

The reissue had the addition of a short sequence that related the progress of Hitler’s blitzkrieg over the face of Europe the preceding year. As in the 1939 version, the courtroom scene ends with the exact words of U.S. District Court Judge John C. Knox to the jury: “In this country we spread no sawdust upon the surface of our prison yards.” This was an allusion to the executions of spies that were almost casually perpetrated in Hitler’s Germany.

Propaganda Never Ages Well

Although it had the endorsement of many civic leaders, the reissue of Confessions was not a success. The American audience that had reacted to the immediacy of the headlines in 1939 was running scared in 1940. Likewise, Nazi progress across Europe in the spring and summer of 1940 had frightened the studios away from other antifascist projects. As Variety reported: “Belief is strong in some [studio] circles that Uncle Sam will crack down on American distribution of any films objectionable to Adolf Hitler should he happen to come out on top in the European conflict.”

Although the subject of the war in Europe would crop up in films for another year, it was not until Pearl Harbor and the subsequent silencing of U.S. isolationist voices that films with the punch and outrage of Confessions of a Nazi Spy could be produced again for a more willing public.

Propaganda never ages well. Viewed today, Confessions of a Nazi Spy might appear to be merely an isolated curiosity from a more impassioned period in American history. Yet it is an intriguing time capsule. There is an odd parallel between getting the reviewers of the period to look seriously at what the film was saying and convincing the U.S. government and the general populace to acknowledge what the Nazi underground was doing. The Depression brought disorder and dislocation to American society. It turned isolationists in on themselves. Small wonder that even J. Edgar Hoover would choose to avoid investigating any group that promised order.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments