By Jon Diamond

As aptly stated by historian Max Hastings in his book Warriors, “the leaders most readily admired by fellow-soldiers are those who seem committed to do their duty, and also to bring every possible man home alive.”

Captain (later Admiral) William George Tennant, Royal Navy, who had vital command responsibilities and made critical decisions at crucial moments during the British evacuation at Dunkirk in May-June 1940 and at the sinking of the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and the battleship HMS Prince of Wales in the early days of the Pacific conflict in December 1941, proved himself such a leader. Although less popularly celebrated than many of his contemporaries in post-war history books and journals, his feats during these two operations and in the design and implementation of artificial harbors at Normandy in 1944 attest to his courage, intellect, and leadership.

William George Tennant was born on January 2, 1890, in Upton-on-Severn. He joined the Royal Navy at just age 15, being sent to the Junior Naval College on the Isle of Wight and later to the training ship HMS Britannia. Specializing in navigation, he saw action during World War I in naval operations in Heligoland and Dogger Bank. Portending his service in World War II, he was involved in the evacuation of troops from Gallipoli. He also saw service at the Battle of Jutland and survived the sinking of his ship by German U-boat torpedoes in the North Sea. During the 1920s, he was promoted to lieutenant commander and navigator aboard the cruisers HMS Renown and then HMS Repulse, taking part in two royal world tours. In recognition of these duties, he was promoted to commander and awarded the MVO (Member of the Victorian Order).

But Tennant’s pivotal roles in naval history came during World War II. On May 26, 1940, as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was being battered and started its retreat through Flanders and northern France, Captain Tennant, Chief Staff Officer to the First Sea Lord (who had just been appointed captain of HMS Repulse), had volunteered to Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, commander of Operation Dynamo, to help with the Army’s evacuation at Dunkirk. Ramsay ordered him to Dunkirk as Senior Naval Officer (SNO) ashore, and early on the afternoon of May 27, he sailed from Dover with 12 officers and 160 ratings, together with a communications staff aboard the destroyer HMS Wolfhound. Every 30 minutes, the Wolfhound was attacked by Nazi dive bombers on the passage across. While the British gunners had no great success against the Luftwaffe’s planes, the attacks helped Tennant realize just how harrowing the Channel crossing was to be.

As Tennant went ashore at 1800 hours to contact the British army commanders in the town, he said, “The sight of Dunkirk gave one a rather hollow feeling in the pit of the stomach. The Boche had been going for it pretty hard, there was not a pane of glass left anywhere and most of it was still unswept in the center of the streets.”

Tennant swiftly assessed the situation of the docks as unusable and stationed his sailors along the beaches east of Dunkirk to act as shore police. Only ashore for two hours, Tennant made the first of his several brilliant decisions, which would favorably impact the evacuation. At 2000 hours, he notified Admiral Ramsay, “Please send every available craft to beaches east of Dunkirk immediately. Evacuation tomorrow night is problematical.” Thus, Tennant determined that the town of Dunkirk and its harbors were not going to be points of embarkation and importantly informed Operation Dynamo’s control center in Dover of this fact. The beaches east of Dunkirk were to be utilized immediately, at least for the time being.

According to Walter Lord in The Miracle of Dunkirk, “Captain Tennant, making his inspection of the beaches as SNO, personally addressed several jittery groups. He urged them to keep calm and stay under cover as much as possible. He assured them that plenty of ships were coming, and that they would all get safely back to England. He was invariably successful, partly because the ordinary Tommy had such blind faith in the Royal Navy, but also because Tennant looked like an officer. In his well-cut navy blues, with his brass buttons and four gold stripes, he had authority written all over him.”

Tennant continued to direct a stream of urgent requests to Dover for more rescue vessels. Although privately convinced that he and his naval shore party would either perish or enter into captivity, he exhibited the traditional British military sang-froid by reporting cheerfully to Dover, “I am getting along splendidly here.”

Tennant realized the evacuation process from the beaches was impossibly slow. Small groups of men were picked up here and a few more there. Out of desperation, Tennant re-examined Dunkirk’s outer harbor and the beaches east of the town. Although the Luftwaffe had set Dunkirk’s piers and quays ablaze, the two long breakwaters or “moles” that formed the entrance to Dunkirk’s harbor were intact. The clouds of smoke from the German air assault and the Wehrmacht’s artillery barrages on the town of Dunkirk hung low over the harbor, impairing visibility to and from the air.

The moles were a mile apart at the land side and angled toward each other into the open water. Made of concrete pilings and covered with an eight-foot-wide boardwalk, it seemed risky to Tennant to try to bring ships alongside the moles to tie up. However, if large numbers of men were to be evacuated by ship, there was no other way. The West Mole was only about 500 feet long, and the water at its near end seemed dangerously shallow. But the East Mole attracted Tennant’s attention as it ran some 1,400 yards out to sea. The base of the East Mole ran right into the sandy beach at the town limits of Dunkirk where the holiday resort of Malo-les-Bains begins.

Tennant saw that troops could be mustered on the dunes and beaches of Malo-les-Bains and marched in groups straight onto the mole and along the walkway. Thus, there was no need for the men to enter the fiery inferno of Dunkirk itself. Under their own officers, supervised by Tennant’s naval shore party, the beleaguered troops could exit from their makeshift beach trenches right onto the evacuating ships.

During the evening of May 27, Tennant directed the ferry Queen of the Channel to enter the harbor and tie up at the East Mole. The vessel eased into place alongside the breakwater, and to Tennant’s relief was quickly and safely secured. This experiment demonstrated very quickly to Tennant that although not ideal the East Mole was preferable to the alternatives offered on the open beach. At 0436 hours on May 28, a signal went to Ramsay in Dover requesting an alteration in plans. Now Tennant wanted as many ships as possible, especially the fast modern destroyers, not off the beaches but alongside the East Mole. This modification in evacuation tactics, using the East Mole, would prove to be the pathway to safety for almost 200,000 of the total 338,000 British and French troops embarked over the next several days. This was Tennant’s second crucial decision.

Unfortunately, British destroyer losses at sea were beginning to mount by the morning hours of May 29. About 1500 hours, weather conditions for the evacuation took a turn for the worse from the Allied perspective. The wind shifted toward the north, clearing the smoke that had covered the port all morning. Conditions were now ideal for the Luftwaffe to deliver one of the most disastrous air onslaughts on the ships conducting Operation Dynamo. Three destroyers, Wakeful, Grafton, and Grenade, were sunk and six more badly damaged.

However, on the following day, May 30, the East Mole, despite the bombing, was still usable. Tennant sent Ramsay a cable in which he stated that Dunkirk would be “untenable” by the next morning. Embarkation, Tennant added, “…could continue until then, but its effectiveness would depend upon large ships and destroyers being sent to the East Mole that night.” He reminded Ramsay, “…a destroyer going full out, with her boats to the beaches, could only embark 600 men in 12 hours, whereas this could be done in 20 minutes at the mole.”

Prompted by the urgent tenor of Tennant’s cable, early that afternoon Ramsay phoned First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Dudley Pound in London and insisted that the modern destroyers must be returned to the evacuation operation if it was to prove successful in the time left. After a heated exchange, Admiral Pound finally relented, and at 1530 hours the destroyers were ordered back to Dunkirk. Thus, another tactical decision adjustment by Tennant continued to help augment the number of evacuees from Dunkirk, primarily via the East Mole. The peak of the evacuation occurred on May30.

At Dunkirk during the late afternoon of June 1, Captain Tennant became alarmed by the damage that the German planes were inflicting on the rescue ships. Tennant witnessed the old destroyer HMS Worcester being pounded every five minutes without mercy, leaving over 350 dead and 400 wounded. Tennant radioed Ramsay, “Things are getting very hot for ships; over 100 bombs since 0530 hours; many casualties. Have directed that no ships sail during daylight. Evacuation of transports therefore ceases at 0300 hours.” Although, maybe less critical than his earlier decisions on the impact of the evacuation, Tennant’s recommendation to Ramsay demonstrates his zeal as a commander to continue an operation’s peak efficiency while minimizing needless casualties by modifying the conditions of battle.

On June 2 at 2250 hours, Captain Tennant loaded the last of his naval party onto a torpedo boat. He radioed Ramsay at 2330 hours, “Operation Dynamo complete. Returning to Dover,” a message that was abbreviated to the more triumphant one, “BEF evacuated.”

Regarding his shining moments at Dunkirk, Vice Admiral Ramsay was to declare, “Without Tennant and his men, the troops would have been lost like sheep.” Vice Admiral Sir Kenneth Buckley recalled, “Bill Tennant’s tall athletic figure in blue strode fearlessly over the beaches giving orders to largely demoralized ‘brown jobs’ and being obeyed.” For his actions at Dunkirk, Captain Tennant was awarded the CB (Companion of the Bath) and France’s Legion of Honour and Croix de Guerre with Palm. The nickname he was, thereafter, given by ordinary sailors, “Dunkirk Joe,” indicates the key role he played in the evacuation of the Allied troops in the dark days of 1940. At a personal level, Tennant was the human embodiment of the term “military leader.”

After Operation Dynamo, Tennant returned to the command of HMS Repulse. In May 1941, he took part with the Eastern fleet in the action to trap the German battleship Bismarck. The sailing of aircraft carrier HMS Victorious and Repulse had been canceled by the Admiralty, and they were placed at the disposal of the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet. The Victorious was already at Scapa Flow, and the Repulse was ordered to sail from the Clyde to join her. However, it was later in December 1941 in the Pacific Ocean that Tennant was to enter history’s limelight again.

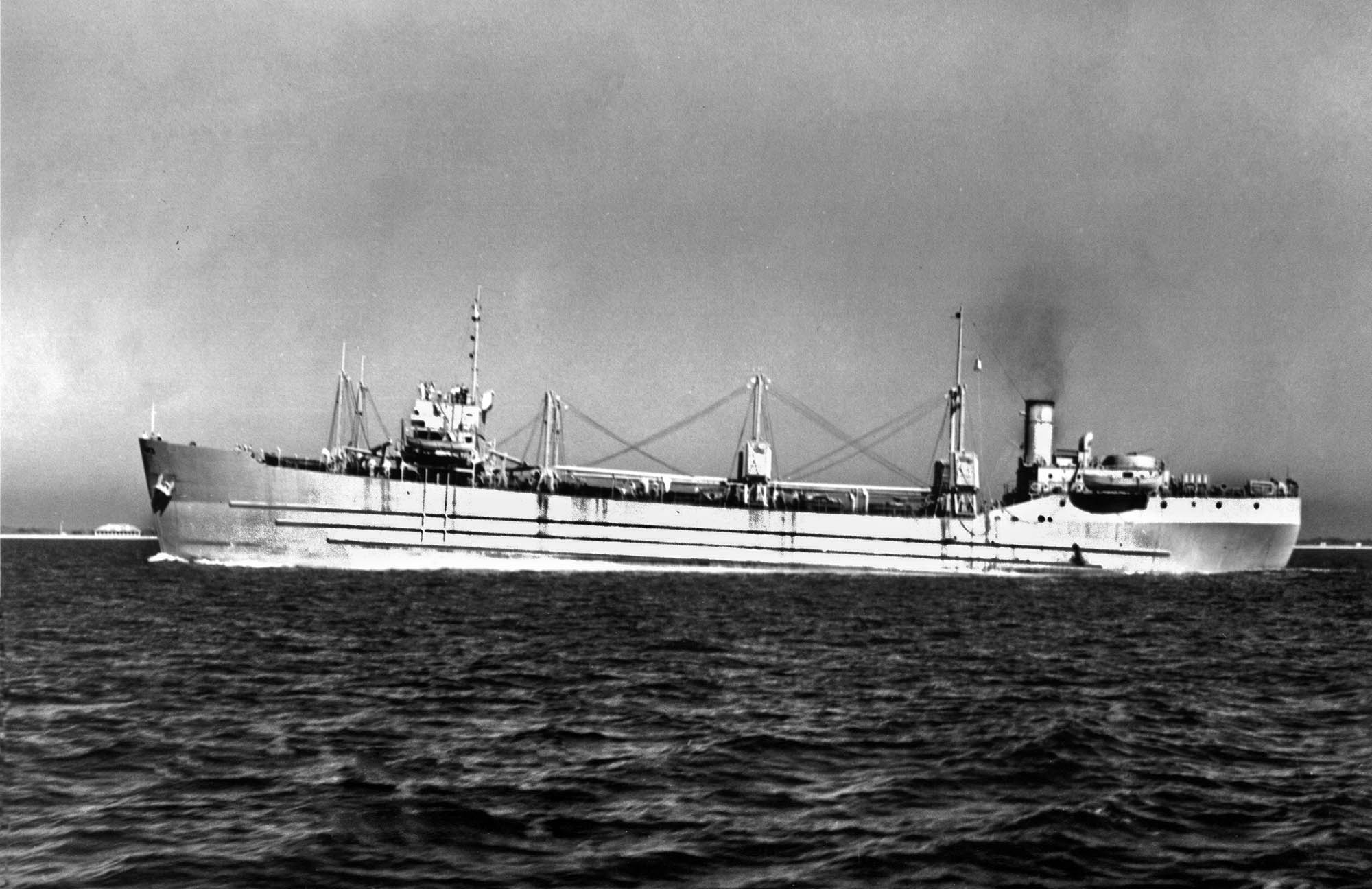

The sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse was a seminal naval engagement in World War II, which illustrated the effectiveness of aerial attacks against naval forces that were not protected by air cover and the resulting importance of including an aircraft carrier in any major fleet action. The disaster took place east of Malaya, near Kuantan, Pahang, where Force Z, as the two British warships were designated, was attacked by Imperial Japanese Navy level and torpedo bombers. The original British plan had called for a larger fleet which included the new Illustrious-class aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable for air cover, although the plan had to be revised when Indomitable was damaged en route. Ultimately, it was Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s decision to allocate these two capital ships to Singapore’s defense; however, it was only a token compromise to demonstrate the British need to protect its various colonial territories in Malaya, Borneo, and the Straits Settlements.

At 1113 hours on December 10, 1941, the Repulse and Prince of Wales were attacked. High-level bombers scored a hit on the hangar deck of the Repulse, which started a small fire. At 1140 hours, six torpedoes hit the Prince of Wales. Meanwhile, Captain Tennant had sent an emergency radio signal to Singapore at 1150 that Force Z was being attacked. This was the only signal ever received on shore to indicate that air support was urgently needed by the Prince of Wales and Repulse.

Six minutes after the solitary signal requesting air cover was sent, Tennant showed incredible skill of maneuver and succeeded in evading all the tracks of nine torpedoes launched by a further group of torpedo bombers, and two minutes later Repulse was missed by high-level bombers. Tennant now brought the Repulse closer to the Prince of Wales to ask if he could assist her; there was no reply.

Soon it was Repulse’s turn again to be attacked. A group of nine torpedo bombers was spotted low on the horizon off the starboard bow. One torpedo struck amidships “with a great jarring shudder, as though a giant hand had shaken the ship,” recalled one officer. Yet Repulse still steamed at 25 knots; still her 4-inch guns and eight-barreled pom-poms attempted to provide antiaircraft artillery cover for the wounded ship. Repulse was hit by more torpedoes as the Japanese planes were attacking from all directions.

With Repulse now listing heavily, Captain Tennant ordered everyone on deck. Again, he demonstrated decisive leadership. He later reflected, “The decision for a commanding officer to cease all work in the ship below, is an exceedingly difficult one, but knowing the ship’s construction I felt very sure that she would not survive four torpedoes, and this was borne out, for she only remained afloat six or seven minutes after I gave the order for everyone to come on deck.”

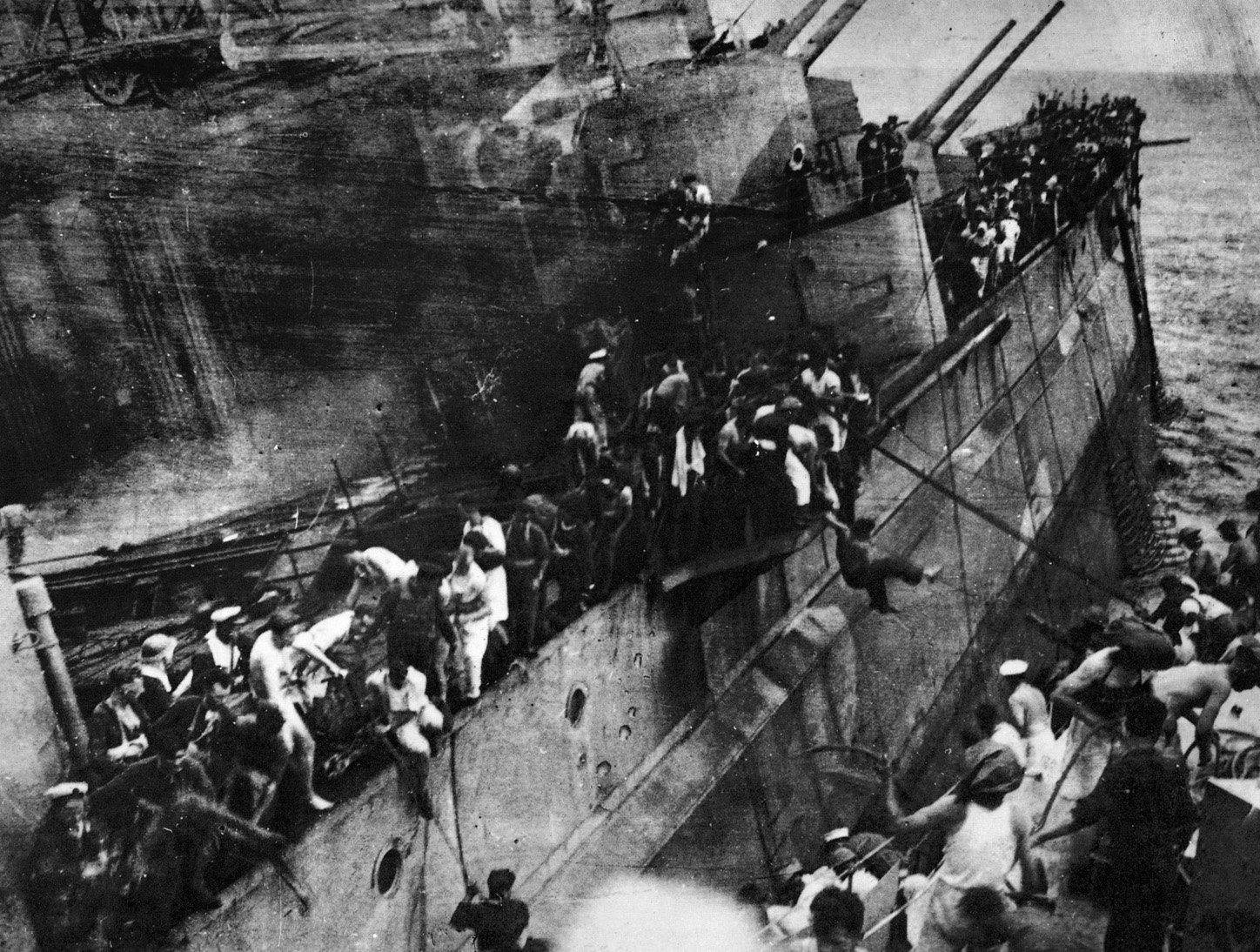

Captain Tennant remembered seeing 200-300 men collecting on the starboard side of the ship prior to its rolling over. He recalled, “I never saw the slightest sign of panic or ill discipline. I told them from the bridge how well they had fought the ship, and wished them good luck.”

The destroyers Electra and Vampire picked up the survivors, who numbered 42 of 66 officers and 754 of 1,240 ratings. As the Prince of Wales went down, 11 Royal Air Force (RAF) Brewster Buffalo fighters arrived on the scene, prompting a distant group of Japanese bombers to jettison their bombs and make for home. Tennant’s emergency signal had been received at 1219 hours, and the Buffaloes were in the air only seven minutes later. Now the Buffaloes patrolled overhead while the survivors of both ships were being picked out of the water or from floats and lifeboats. It has been reported that while swimming for their lives the survivors of the Repulse gave three cheers for their captain and their lost ship.

Curiously enough, the men were far from dispirited, as one pilot reported later: “It was obvious that the three destroyers were going to take hours to pick up those hundreds of men clinging to bits of wreckage and swimming around in filthy, oily water. About all this the threat of another bombing and machine gun attack was imminent. Every one of those men must have realized that. Yet as I flew round every man waved and put up his thumb as I flew over him. It shook me, for here was something above human nature.”

According to Churchill’s History of the Second World War, “Captain Tennant realized that his ship was doomed. He promptly ordered all hands on deck, and there is no doubt that this timely action saved many lives.”

Shifting back to the Atlantic and the feverish preparation for Operation Overlord and the invasion of Normandy, a major problem confronted the Royal Navy. The transport and installation of the artificial harbors (Mulberries) after the invasion had commenced presented a colossal undertaking in itself. To take complete charge of this “devil” of a task, the now Rear Admiral Tennant had been appointed to Ramsay’s staff in January 1944.

Tennant immediately doubted whether the Phoenix breakwaters, comprising the Mulberry artificial harbors, could withstand even a moderate gale. Moreover, since it would be nearly three weeks before all had been towed over and put in place, he thought that in any case some other kind of shelter must be immediately provided for small craft off the beaches. He therefore proposed that obsolete ships should be sunk stem to stern as breakwaters.

Prime Minister Churchill approved; 55 old merchant ships and four redundant warships were to be prepared as blockships to be scuttled to form five shelters (one in each of the five assault areas, including the two Mulberries) code named Gooseberries. Rear Admiral Tennant was in charge too, of the laying of the cross-Channel Pluto pipeline supplying vital fuel for the same Normandy invasion. For his part in the success of the D-Day landings, Tennant was awarded the Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) by King George VI and the United States Legion of Merit.

In 1945, Vice Admiral Tennant was awarded a knighthood for “distinguished war service,” and from 1946 until 1949, he served as Commander-in-Chief of the American and West Indies Station headquartered in Bermuda. Tennant was promoted to admiral in 1948 and retired the following year at the age of 59. He died in 1958 after a distinguished public service career in Worcestershire.

Few officers are presented a single opportunity to command during the chaos and carnage of battle and demonstrate the leadership qualities which enable them to be labeled true warriors. William Tennant on numerous occasions, by exhibiting tactical and strategic wisdom as well as composure under fire, was such a brilliant leader who was committed to the proper discharge of his duty and bringing as many men home alive as possible.

Jon Diamond lives and practices medicine in Hershey, Pennsylvania. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments