By Eric Niderost

By the 1930s, Shanghai was already a legend in its own time––the most modern, populous, and decadent city in China. The Shanghainese worshipped Western culture, and the stylistic Art Deco architecture was all the rage. High-rise buildings sprouted like mushrooms until there were more skyscrapers in Shanghai than anywhere else in the world outside of New York and Chicago.

Bridge House was a good example of these buildings. The eight-story hotel’s name derived from the North Szechuan Road Bridge that spanned nearby Soochow (now Suzhou) Creek. Built around 1935, it was an ordinary Chinese hotel, one of many in the growing metropolis. The architecture was typical for the period, with an off-white façade and Art Deco touches.

Despite its architectural details, this building at 478 North Szechuan Road was so ordinary as to be anonymous. Yet it was destined to be the most infamous and dreadedplace in all Shanghai—the Japanese equivalent of the Gestapo’s Columbia-Haus in Berlin. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people were imprisoned here from 1937 to 1945, many suffering unspeakable torture at the hands of brutal Japanese captors.

The story of Bridge House is a harrowing tale of agonizing pain and obscene brutality but also of human courage and endurance in the face of death. Its first victims were Chinese, but after Pearl Harbor a steady stream of Allied civilians and POWs found themselves incarcerated there. The portals of Bridge House were unmarked but should have borne a legend echoing that of Dante’s Inferno: “Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here”

The International Settlement in Shanghai

This hellish hostelry cannot be fully understood without some background history. Shanghai, in the 1930s, was divided into three different entities. The International Settlement was a product of China’s weakness in the 19th century. Technically Chinese soil, it was really a separate enclave ruled by a 14-man Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC). There were five British councilmen, two Americans, two Japanese, and five Chinese.

The French Concession was, in essence, a colonial possession of France, adjoining the International Settlement but rarely cooperating with it. The rest of the city was known as Greater Shanghai. Before 1937 it was ruled by the Chinese central government based in Nanking (Nanjing), which appointed its mayor and other functionaries.

When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in the summer of 1937, Chang Kai-shek, the Chinese head of state, decided to make a stand against the invaders at Shanghai. The Chinese proved courageous fighters, contesting every inch of their soil, but after three months of bloodshed, the Japanese gained the upper hand. Battered Chinese divisions retreated up the Yangtze River, leaving the Japanese in control of Greater Shanghai.

Conquest followed the usual patterns. The Japanese established the Dadao (Chinese for “Great Way”) Municipal Government, a body that was supposed to be dedicated to reform. It was a transparent ploy, and even the simplest Chinese coolie could not fail to recognize the government’s true nature as a Japanese puppet.

In reality, the Japanese, like the Romans, had “made a desert and called it peace.” Whole sections of the Chapei District had been laid waste because of the fighting, while other districts were ruthlessly stripped of anything of value. Every pipe, appliance, and bathroom fixture that could be found was ripped out of buildings and turned to scrap.

But the Japanese could not take over the International Settlement without risking war with Britain and the United States. The Settlement became a “Lonely Island,” a small patch of unoccupied ground in a Japanese “sea.” Technically, the Japanese did have a foothold in the Settlement, namely the Chapei and Hongkew Districts. Hongkew in particular was eventually home to some 30,000 Japanese, so many that it was dubbed “Little Tokyo.”

The Anglo-American “core” of the Settlement, which included the famous Bund waterfront, was separated by a snaking waterway called Soochow Creek. It became a kind of unofficial international boundary, like the Rio Grande in North America, albeit on a much smaller scale. Several bridges crossed the creek, including Garden Bridge, where Japanese sentries patrolled one end of the span and British troops guarded the other, the “Bund” side.

The Bridge House Hotel: Secret Prison of the Kempeitai

It was probably about this time that Bridge House was established as a prison by the Kempeitai, the Imperial Japanese Army’s ruthless military police—Westerners called them gendarmerie. The hotel was certainly up and running as a clandestine prison by 1937.

The Kempeitai acquired a sinister reputation as time went on. Chinese staff and hotel guests were presumably evicted, and the rooms were converted into cells and torture chambers. Bridge House became not just a prison but the regional Kempeitai headquarters for Shanghai.

During the “lonely island years,” 1937-1941, victims were Chinese. Most Westerners were completely unaware that the hotel was now a prison even though it was a mere two blocks from Shanghai’s classically designed Central Post Office, an impressive landmark even today. People bought stamps and posted letters (though there were Japanese censors on the premises), little knowing that others were being tortured to death just a three-minute walk away.

The Kempeitai’s War on Journalists

Temporarily safe on neutral ground, courageous Chinese, American, and British journalists exposed Japan’s atrocities and lust for conquest. One of these was John Benjamin Powell, editor and publisher of the China Weekly Review and China Press. Outspoken and unafraid, Powell was pro-Chinese and made no apologies for it.

Hallett Abend, correspondent for the New York Times, was another thorn in the Japanese side. Abend exposed Japanese aggression and was not shy about naming names.

Major General Saburo Miura, who headed the Shanghai Kempeitai from 1939 to the end of 1940, took a particular dislike to Abend. Two armed thugs invaded Abend’s apartment in Broadway Mansions, searching for materials the American had written allegedly “insulting the Japanese Army.” His apartment was ransacked and Abend himself was brutalized and badly beaten. It was a foretaste of what was to come.

Ironically, Broadway Mansions was in Hongkew, in the Japanese-dominated section of Shanghai. Knowing this, Abend was in the process of moving to the other side of Soochow Creek when the assault occurred. In spite of his grievous injuries, Abend was lucky. He lived on the 16th floor, and the Kempaeitrai agents could have flung him out the window to his death.

Abend finally left Shanghai in the fall of 1940, so was spared the terror to come. In July 1940, the Japanese issued a blacklist of foreign and Chinese journalists who were earmarked for “deportation;” John B. Powell’s name was on the top of the list. Shortly thereafter, a Japanese agent tried to assassinate Powell near the American Club on Foochow (now Fuzhou) Road.

Powell was hit in the back by a foreign object, nearly knocking him over. The editor discovered to his horror it was an unexploded Japanese hand grenade. In his haste, the would-be assassin had failed to fully pull the pin. Thereafter, Powell worked largely at night.

Others were not so fortunate. It was open season for Chinese editors foolish enough to take an anti-Japanese stand. Tsai Diao-tu’s severed head was found in the French Concession with a note tied to it that read, “Look! Look! The result of anti-Japanese elements.” Many more assassinations followed, no doubt orchestrated by the Kempetai.

The Japanese Invade the International Settlement

The hell of Bridge House was revealed after December 8, 1941, the day the Japanese took over the International Settlement in the wake of Pearl Harbor. Since Japan was at war with the United States and Great Britain, there was no need to observe diplomatic niceties, or render even lip service to international law. The Kempeitai, called “Japan’s Gestapo,” seemed hell bent on living up to the comparison.

The Kempeitai had several categories of victims. First on the list were British and American journalists, men who had dared to insult the Japanese nation by exposing the truth about its Army’s brutal activities.

Next were bankers and corporate executives—mostly American, British, and a few other nationalists—who had been living in Shanghai when war broke out. If they were financiers or bankers, they could be forced to cooperate, or even be tortured to reveal “hidden funds.” Foreign businessmen were suspected of espionage, and torture might loosen tongues to gain “information.” The vast majority of these “espionage rings” were products of Japanese paranoia and fantasy that bordered on the delusional.

As the months progressed, Allied POWs were incarcerated in Bridge House. Usually there were “in transit,” destined for another prisons, but they suffered beatings and privations while at 478 North Szechuan Road. The last category of inmate is perhaps the strangest of all—Japanese soldiers who were “insubordinate,” or had refused duty.

The Roundup

For the first few days after the Japanese takeover of Shanghai, all was fairly normal. It was a deceptive calm before a terrible storm. Most of the men marked for apparent arrest still remained at liberty. Lulled into a sense of euphoria by this sudden turn of events, the Anglo-American community breathed a collective sigh of relief.

True, the Japanese had taken over places such as the American Club, forcing residents like Powell to vacate within two hours, but at least there were no arrests. The roundups began a few days later. Kempeitai agents broke into John Powell’s room at the Metropole Hotel in the wee hours of December 20, 1941. As the American was taken into custody, his rooms were thoroughly searched for “evidence.” His China Weekly Review and China Press offices had been shut down and sealed, but Powell still had papers, letters, and other materials with him in his rooms. The apartment was ransacked.

Powell was taken by elevator to the lobby and hustled outside into a waiting car. It was only a short drive across Soochow Creek to Bridge House. One can well imagine the thoughts that ran through Powell’s head during this trip to hell. He was initially told that he’d only be “questioned.” There was no hint of permanent incarceration, at least not at this stage.

Soon American military personnel began to be held at Bridge House. Lt. Cmdr. Columbus Darwin Smith, USNR, skipper of the gunboat USS Wake, was at first treated as a POW. After an unsuccessful escape attempt, he was sent to Bridge House for Kempeitai ”investigation.”

”I took a deep breath as I went through the big doors of Bridge House,” Smith later remarked. “I turned and looked at the warm sun and wondered if I’d ever see it again.” Scores of other victims no doubt felt the same.

Crammed Into Small Cells

In the early months the Japanese showed relative restraint with British and American prisoners, perhaps because Allied consular staff were still there, waiting to be repatriated to their home countries. Once the diplomats were gone, the mistreatment and torture grew worse.

Hugh Collar was British, the director of Imperial Chemical Industries. As chairman of the British Resident’s Association, he was a high-profile target responsible for the actions of his fellow countrymen. Before he was arrested, Collar tried to get food parcels to Bridge House prisoners. Eventually he found himself a Bridge House victim himself.

Collar left a detailed, chilling account of his arrest and subsequent stay at the infamous prison. He noted that arrests were usually carried out around 2:00 am, when the victim was sleepy and disoriented. Like Powell, Collar was driven to Bridge House and processed without delay. The prisoners had to remove their shoes and surrender all items in their pockets. These were placed in an envelope and carefully labeled with the prisoner’s name.

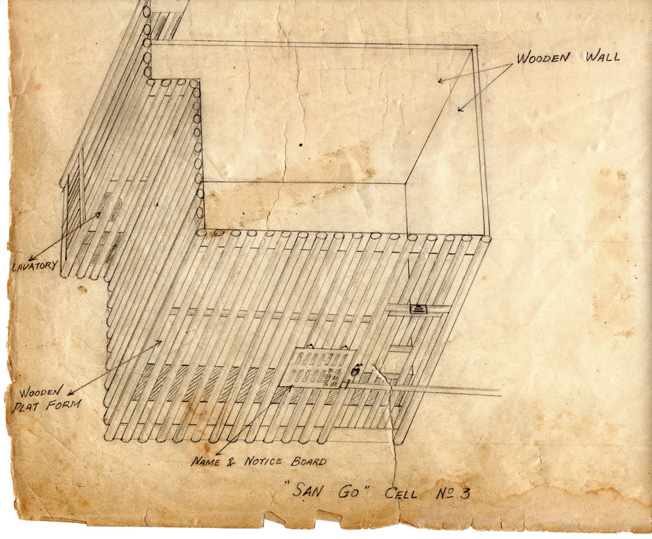

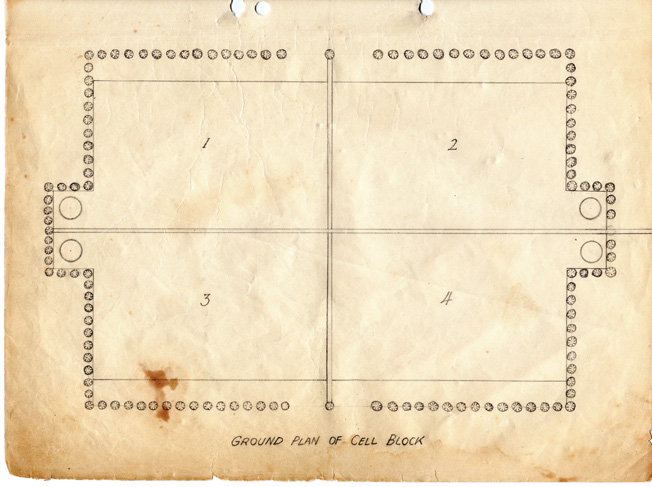

Prisoners––men and women alike––were then shoved into cells. Powell recalled that there were 15 cells in Bridge House’s main building. The newsman had cell number 5, which was enclosed on three sides. The fourth side had a door, which was built of wooden bars some six inches thick, spaced about two inches apart. There was also a space in the door where food was delivered on a sometimes irregular basis.

Cells seem to have varied in diameter; Collar remembered a “ten by ten” foot chamber, while Commander Smith recalled his cell was “ten by twelve” feet. Whatever the dimensions, each cell was crowded with a dozen or more inmates. It was a newly arrived prisoner’s first taste of the horrors to come.

“As Filthy As Human Beings Could Be”

British businessman Henry Pringle described the cells as having wooden bars on two sides and wooden walls on the other two sides. The floor was a sort of wooden platform that was raised about two inches above a concrete floor. Since the place was unheated, prisoners suffered from cold as well as torture.

As his or her eyes adjusted to the dim light, a new prisoner would see “perhaps twelve, fifteen, or twenty shapeless lumps you assume to be people,” according to Collar. Almost simultaneously, the cell’s stench would assault one’s nostrils––a sickening odor of human waste, unwashed bodies, and death.

After a few weeks behind bars, prisoners looked like filthy scarecrows, with matted hair and long, unkempt beards. Smith recalled prisoners were “as filthy as human beings could be.”

Worse still, some inmates were suffering from loathsome diseases, while the bloodied bodies of others showed the marks of recent torture. Toilet “facilities” consisted of a hole in the floor, or a bucket, infrequently emptied.

Powell found that he literally had no place to sit down, but another prisoner recognized him and motioned him over. The man was Rudolf Mayer, brother of Louis B. Mayer, famed head of MGM Studios in Hollywood. Mayer had no idea why he had been arrested, except perhaps to seek ransom from his brother, one of the most powerful men in the movie industry.

Mayer explained to Powell that there was a space for him against the wall—a precious spot, because one could lean against it. The space had been recently vacated by the death of a Korean prisoner. Bayoneted by a Japanese guard, the Korean was allowed to die of blood poisoning in great agony.

Prisoners were forced to sit or squat in rows on the cell floor, often for hours at a time, in the Asian style, sitting on their heels, which was and is an unnatural position for most Westerners; this facilitated counting.

Heads had to be bowed and faced in the direction of Tokyo, in token of their submission to Emperor Hirohito, Japan’s “living god” and “Son of Heaven.”

Cells were alive with vermin; rats were everywhere. Powell once awoke with a rat tugging at his hair. Prisoners were permitted a two-minute “wash” every week or so, the water provided by a cold-water faucet in the courtyard; no soap was provided to the prisoners. Clothes were never washed and were soon crawling with lice.

Abuse of Chinese Prisoners

Chinese prisoners were treated with special contempt. Japanese guards seemed to take special delight in punishing Chinese for the slightest “infraction” of the rules. When a Chinese prisoner was caught smoking a smuggled cigarette, he was badly beaten. Later, the man developed beriberi and died after a Japanese doctor “treated” him. When another Chinese man was beaten, Powell counted 85 blows with bamboo cudgels before the man’s screams and moans finally ceased.

Most Chinese prisoners refused to be broken by their hated enemy. Lt. Cmdr. Smith became friends with a Chinese man named Wang Lee. Lee, about 30, was quick-witted and agile, with the body of an athlete. Although Lee was an assassin, a killer for hire, a not-uncommon profession in prewar Shanghai, Smith grew to admire him for his courage and resilience.

From time to time Japanese guards would line up the prisoners for a head count. One day, a burly guard ordered Lee to step forward. When Lee obeyed, the guard smashed him in the face with his fist. It was a sledgehammer blow, delivered at full force, and Lee went down on the floor. The Chinese got up, smiling, though a thin trickle of blood seeped from his lips. The guard felled him again, and again Lee got to his feet, shaken but still smiling, which seemed to enrage the guard even further.

The guard hit him a third time, and for a third time Lee was sent sprawling, only to recover and get up again. By the fifth or sixth time, Lee’s face looked like raw hamburger, but he still managed to smile though bruised and bloody lips. This went on and on, until Lee was knocked unconscious by the 13th blow. Satisfied, the guard left Lee on the cell floor.

Smith and the others tried their best to help Lee, but there was little they could do. There was no medicine, no bandages, not even water to wash away the blood. After five hours, Lee finally regained consciousness, battered but triumphant. “I could have done better than that!” he boasted. Lee explained that the guard was humiliated by his inability to deliver a knockout blow. “He lost face badly,” Lee declared. “He will be a laughing stock among his men!”

The Businessmen of Bridge House Hotel

Many British and American businessmen had no idea why they were arrested and imprisoned, yet they were still tortured by sadistic Japanese thugs. Some inmates were among the most prominent members of the Anglo-American Shanghai community, men like Sir Frederick Maze, head of Chinese Maritime Customs; J.M. Mackay of the National City Bank; and Freddie Twogood, director of Standard Oil.

Some were apparently guilty by association. Ellis Hayim was a prominent member of the Sephardic Jewish community and head of the Shanghai Stock Exchange. In the late 1930s, Jewish refugees escaping Nazi persecution flooded into Shanghai, one of the few places on earth willing to accept them. Hayim and other Jewish leaders set up soup kitchens and provided homes and shelter for the penniless unfortunates.

Hayim’s social work brought him into association with Sir Victor Sassoon, a millionaire businessman and real estate developer. Sassoon was a British Jew who was unabashedly pro-Chinese and pro-Allies. During the 1937-1941 period, Sassoon traveled abroad and made statements that condemned the Japanese military; he was lucky enough to be out of the country when the Japanese took over. If arrested, he most assuredly would have been one of the first to experience the “hospitality” of Bridge House.

Cheated of their prey, the Japanese arrested Hayim and his wife. They were also suspicious of Hayim’s many parties before the war, affairs that featured such guests as American Rear Admiral William Glassford.

Oriental Mission Shanghai

Most Anglo-American “plots” existed only in the feverish minds of Kempeitai officials. There was one group, however, that did attempt to set up a sabotage and espionage operation in Shanghai just before Pearl Harbor. This was OM Shanghai (Oriental Mission Shanghai), a branch of the British espionage network Special Operations Executive (SOE).

In May 1941, the fledgling OM Shanghai was given a leader in the person of Valentine St. John Killery, a businessman and former member of the Shanghai Municipal Council. Killery recruited agents, who were given code names and told to be prepared to act in time of war. In retrospect, the effort was doomed from the start, largely because the “agents” were much like Killery himself—middle-aged British businessmen with no experience or training in covert operations.

Members of OM Shanghai included William J. Gande, a 55-year-old liquor importer; Edward Elias, a 42-year-old stockbroker; and W.G. Clarke, a 65-year-old former deputy commissioner of the Shanghai Municipal Police. These men were loyal, courageous, patriotic, and British to the core.

There seems to have been no attempt to recruit native Chinese into OM Shanghai, itself a fatal error. These prominent members of the Anglo-American community were white Europeans in a sea of Asians and, as such, stuck out like sore thumbs. They could hardly have blended in with the local population, so it was easy for the Kempeitai to monitor their movements.

Brave but inept, the OM Shanghai collapsed like a house of cards a few days after Pearl Harbor. On December 17, 1941, W.G. Clarke was taken into custody and hauled off to Bridge House. Tortured almost to the point of death, he was thrown into John Powell’s cell. “I saw he was in severe pain,” Powell later recounted. “He was suffering from several boils on his neck; they had become so infected and swollen, because of lack of medical attention, that his head was pressed over against his shoulder.”

Clarke, in agony, whispered to Powell that he feared he was going to die. The two men recited the Lord’s Prayer, which seemed to give the sufferer some comfort. He was later removed to a hospital.

The other members of OM Shanghai, some six or seven men in all, were arrested 10 days after their unfortunate colleague. All were then sent to Bridge House for torture and interrogation. Another prisoner caught sight of William Gande after the latter was coming back from questioning: ”He looked extremely ill and worn,” the prisoner recalled, “and his head was swathed in bandaging which, from its appearance, had been there for many days.”

The Doctors of Bridge House: Sadists Not Samaritans

Gande was lucky to get even a dirty bandage because medical treatment at Bridge House was medieval at best and nonexistent at worst. For example, John Powell began to have pain in his feet, largely because of the poor diet and forced squatting on the cold floor for weeks on end. Forbidden to move, blood circulation in his feet grew sluggish, and then was virtually cut off. Powell’s feet also developed beriberi, swelled to twice their size, then grew black with gangrene.

There were Japanese doctors and nurses at Bridge House but they were more sadists than Samaritans. In fact, like many of the Nazi doctors at the concentration camps, they seemed to delight in making their patients suffer.

Powell also developed a badly swollen, infected finger. After two weeks of begging for treatment, he was taken to the dispensary. A Japanese medico, Powell later recalled, “literally trimmed all the skin off my finger” without anesthetic. Japanese soldiers “stood about the room and appeared to enjoy my grimaces.”

The pain one endured from hospital “treatment” was a foretaste of the real agony to come. Sooner or later, inmates would be summoned for interrogation––questioning that almost always involved torture. Bridge House’s appalling conditions were bad enough, but torture was the prison hotel’s real claim to enduring infamy.

Interrogation and Torture

Prisoners would sometimes wait for weeks to be called, the sheer terror of what was to come growing in their minds with each passing day. Guards would come to a cell, call out a name, and then drag the victim upstairs to the torture chambers. The prisoners left behind could often hear the screams of victims echoing through the building.

Hugh Collar explained that “every night you hear the thumps, and shrieks and groans, and wonder, quaking inwardly, how you will be able to take it.” Tortured men and women were deliberately returned to their cells, bloody, mutilated, and semiconscious, so that other inmates could see what was in store for them.

Then, finally, another prisoner would be summoned for his or her first interview. The first questioning might take place in the Kempeitai offices on the fourth floor. Powell recalled that the offices of a Lieutenant Yamamoto had a narrow balcony. His guard would laugh, look over its edge, and point down to the pavement below. The Japanese had a habit of getting rid of prisoners by throwing them off tall buildings.

A week or two later, more serious interrogations began. Once the prisoner reached the interrogation chamber, he or she would be stripped completely naked. This was done deliberately to make a victim feel helpless and vulnerable. At first, questions were routine and usually biographical. Name, age, address, names of relatives, friends, and job description were all recorded.

Smith claimed in his memoirs that he bluffed the Japanese out of torturing him by pulling rank and declaring as an American Navy officer he “wouldn’t allow” any abuse. In 1992, though, another former Bridge House prisoner, Marine Charles Brimmer, laughed at Smith’s written allegations. “In my experiences,” he recalled, “the Japs would not have cared if he was MacArthur himself. They did what they did regardless of rank.”

During interrogation two guards were hovering around the prisoner’s chair. They were permitted to smoke, and at first appeared relaxed and cheerful. But when they were finished, they extinguished their cigarettes on the victim’s naked body—at times on the prisoner’s genitals—producing painful burns. Smith said he did not suffer this treatment—the Japanese were inconsistent—but did know cellmates who did. Some had between 200 and 400 burns all over their bodies.

The Water Cure

But the real torture was yet to come. A prisoner would be taken back to his or her cell and not summoned again for a week to 10 days. It was all part of the “softening up” process, designed to break a person’s will and spirit.

Eventually a prisoner would be tortured. A favorite was the “water cure.” The victim was held down and forced to consume water from a five-gallon can. Urine and kerosene would also be added to the revolting mixture. After a victim’s abdomen was swollen, filled to bursting, he would be beaten on the stomach with a light steel rod. Sometimes, a Kempeitai soldier would literally jump on the victim’s water-filled body.

Hugh Collar left an account of what it was like to be given the water cure. “After the first searing pain you don’t feel anything more for a bit; you are out cold, but the coming around is pretty terrible, too.”

The water cure was not only painful; it was often fatal. Smith recalled that two Chinese prisoners who had been given the water cure were returned to their cells, dead. Sometimes, after weeks of torment, victims would literally lose their minds, moaning and babbling insanely.

Other tortures included electric shocks to various parts of the naked body, particularly the genitals. Women were not exempt from the pain and humiliation of these sessions. One Russian woman was thrown back into her cell in terrible condition. Electric shocks had been applied to her nipples, and various sharp objects brutally inserted into her private parts. When she still would not talk, her fingernails were pulled out and her jaw was broken by a heavy blow.

American POWs in Bridge House

Smith wasn’t the only American serviceman to be held in Bridge House. The ex-hotel also housed other Allied military prisoners, men who usually had “lost” their POW status in Japanese eyes. Japan had never signed the Geneva Convention, so they felt free to deal with POWs as they pleased.

Smith discovered this fact to his dismay after an early, failed escape attempt with several other POWs, including U.S. Navy Commander Winfield Scott Cunningham of Wake Island and Commander John B. Woolley of the Royal Navy. By surrendering when their garrisons were overrun (instead of fighting to the death or committing suicide), they had done the “unthinkable” by “deserting” to the Japanese Army in time of war. Further, following their capture after breaking out of Bridge House, Smith and his companions were considered criminals and treated even more harshly.

The Doolittle Raiders

The Doolittle Raiders were another group of “special guests” of the Empire of Japan who suffered brutal incarceration at Bridge House. The Doolittle Raid, named after Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, was one of the great exploits of the war. Sixteen B-25 bombers and 80 airmen took off from the carrier USS Enterprise on April 18, 1942, to bomb targets in Japan.

The raid was a success, and a great morale boost to the American people after a string of depressing defeats at the hands of the Japanese. Tokyo, Nagoya, and Yokohama were all bombed and, although damage was light, the psychological impact on the Japanese high command was immediate and profound.

Low on fuel, all of the B-25s had to ditch in the sea or crashed after the crews bailed out. With one exception, the bombers went down in China, where local Chinese civilians or partisans rescued them and took them to safety. Unfortunately, eight crewmen from bombers No. 6 and No. 16 were captured and treated as war criminals.

These Bridge House prisoners included Lieutenants William Farrow, Robert L. Hite, George Barr, Dean E. Hallmark, Robert J. Meder, Chase J. Nielsen, engineer/gunner Sergeant Harold Spatz, and bombardier Corporal Jacob De Shazer.

Initially, the captives were flown to Tokyo, where they endured the “water cure” and beatings and were hung suspended by their arms. After two months, the eight POWs were flown to Shanghai, where they were thrown into a dirty cell at Bridge House with 15 Chinese prisoners, two of them women. Rations were scanty, including some nearly inedible bread and congee, a kind of rice porridge

The Doolittle prisoners endured Bridge House’s “hospitality” for 70 days, then they were transferred to another prison. However, since the Japanese considered Doolittle’s aviators “war criminals,” three of the captives—Farrow, Hallmark, and Spatz—were executed on October 15, 1942.

The 1942 Prisoner Exchange

As the war dragged on, there seemed to be no end to Bridge House’s prisoners. Some were lucky enough to be released and repatriated when a prisoner exchange was arranged between the U.S. and Japanese governments. About 1,500 Japanese living in the United States were swapped for 639 Americans, some Canadians, and a few South Americans in an arrangement that took place in June 1942. The Western captives sailed on the Italian liner Conte Verde, with the actual exchange occurring on the neutral island of Portuguese Mozambique. After two or three exchanges, the program was halted and no more exchanges took place after August 1942 until the end of the war.

The welfare of American, British, and Dutch citizens in Shanghai was the responsibility of Swiss Consul General Emile Fontenel but he was forbidden from ever visiting Bridge House. Before leaving the infamous prison, the prisoners were forced to sign a statement that they were in “good health” and “all right.” The signed statements were supposed to assuage Fontenel’s suspicions about the prison.

John Powell was one of those lucky enough to be on the exchange list. Even before repatriation, he had been transferred to Shanghai’s Kiangwan prison, which had better food and living conditions—at least compared to Bridge House.

Before leaving Kiangwan prison, he was forced to sign one of the “good health” statements, but Powell was far from “all right.” When he entered the prison, he weighed 160 pounds; when he was finally released, he was a wasted 75 pounds, little more than a living skeleton.

By some miracle, Powell was transferred from Kiangwan to Shanghai’s General Hospital. His heath marginally improved but he was in severe pain from his bloated, blackened feet. The gangrene that had set in was so serious there was talk of amputation.

Once repatriated and back in the United States, Powell underwent a series of treatments and operations. There was little the doctors could do—first his toes, and then the front portions of his feet were amputated, leaving him with only heel stumps. Courageous as always, he learned to walk again with the aid of specially built shoes. Sadly, Powell died in 1947, his health broken by his ordeal.

Some of the British were also repatriated, while others sat out the war in internment camps. Those repatriated included members of OM Shanghai. As before, prisoners were forbidden to spread “false rumors” about their experiences. When some Americans revealed the tortures and obscene cruelty of Bridge House, the Japanese branded the stories as “lies.”

Destroying Evidence of the Crimes of Bridge House

Bridge House continued to operate until the end of the war. When Japan surrendered in 1945, Kempeitai officials and soldiers at Bridge House went to work destroying all incriminating evidence. It was said that several bonfires in the courtyard were kept blazing for days. When all evidence was destroyed, the Kempeitai stripped Bridge House of anything valuable, loaded the booty onto trucks, and drove away.

Bridge House fell into obscurity, and its subsequent history after 1945 is somewhat obscure. At one time or another, it was remodeled, becoming an apartment building instead of a hotel. Bridge House, with stores on the ground (first) floor, where giggling Chinese teenaged girls shop for the latest fashions, is still occupied today, its residents apparently unaware of its infamous past.

For anyone who cares to look, there is a small plaque but no real memorial to the time when the former Art Deco hotel was devoted to torture and death rather than housing and commerce.

I wonder why the brutality of the Japanese war criminals were never reported on as well as the German nazi were. Few know very little.