by Mark Carlson

The era of the battleship reached its apogee at Tsushima Strait in May 1905, when Admiral Heihachiro Togo’s powerful Japanese battleships annihilated the Russian fleet in the Russo-Japanese War. After Tsushima, no major naval engagement between capital ships would have more than a trifling effect on the outcome of any war.

But the long-cherished belief that battleships could decide the fates of nations refused to die, even more than 30 years later. That was the case on a tragic day in May 1941, when two British warships, the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the pride of the Royal Navy, the huge battlecruiser HMS Hood, emerged from the dawn to face the German battleship Bismarck.

The Bismarck, the newest German warship and the most powerful one ever built, was accompanied by the smaller but equally dangerous heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen as they raced southwest through the Denmark Strait towards the open Atlantic. Prince of Wales and Hood were there to stop the Germans at all costs.

The pivotal moment in a duel that lasted only minutes began at 5:51 AM on May 24, when the two Royal Navy warships turned to close with the two German ships on the western horizon. The range was 28,000 yards (15.8 miles). Hood had to move closer to give her shorter-ranging guns a better chance of hitting Bismarck. Soon the guns on all four combatants were firing.

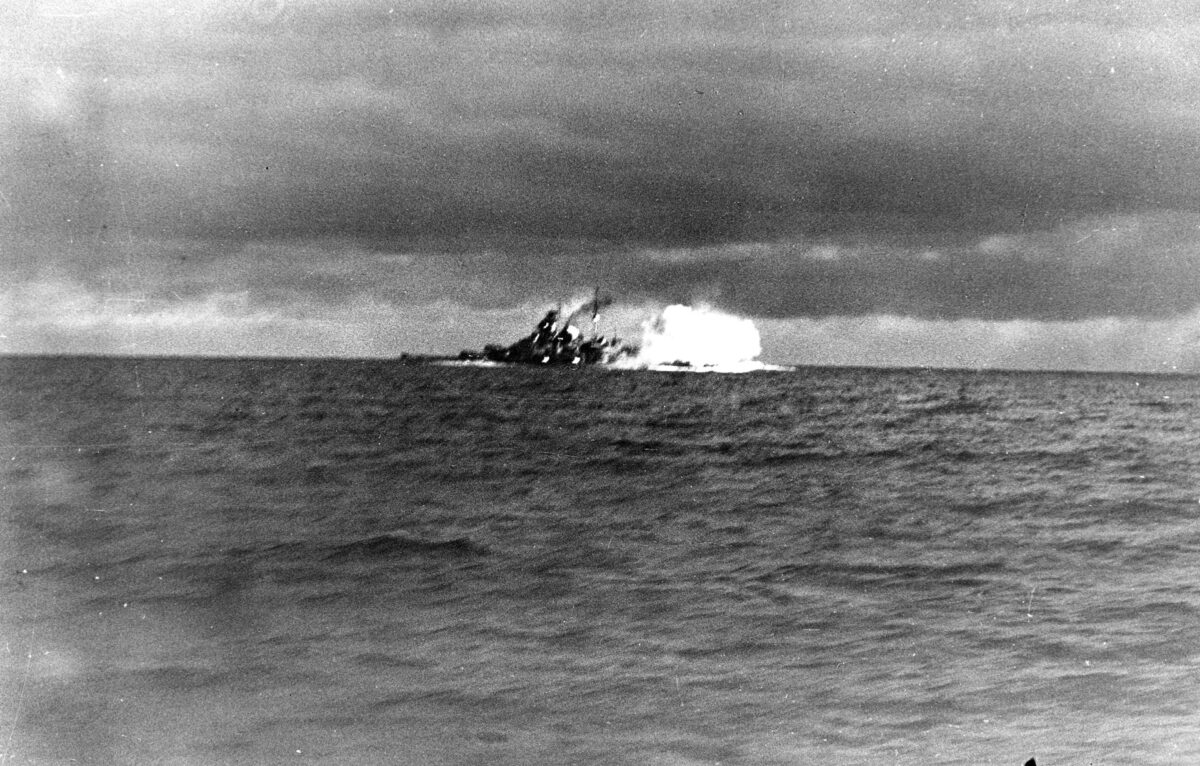

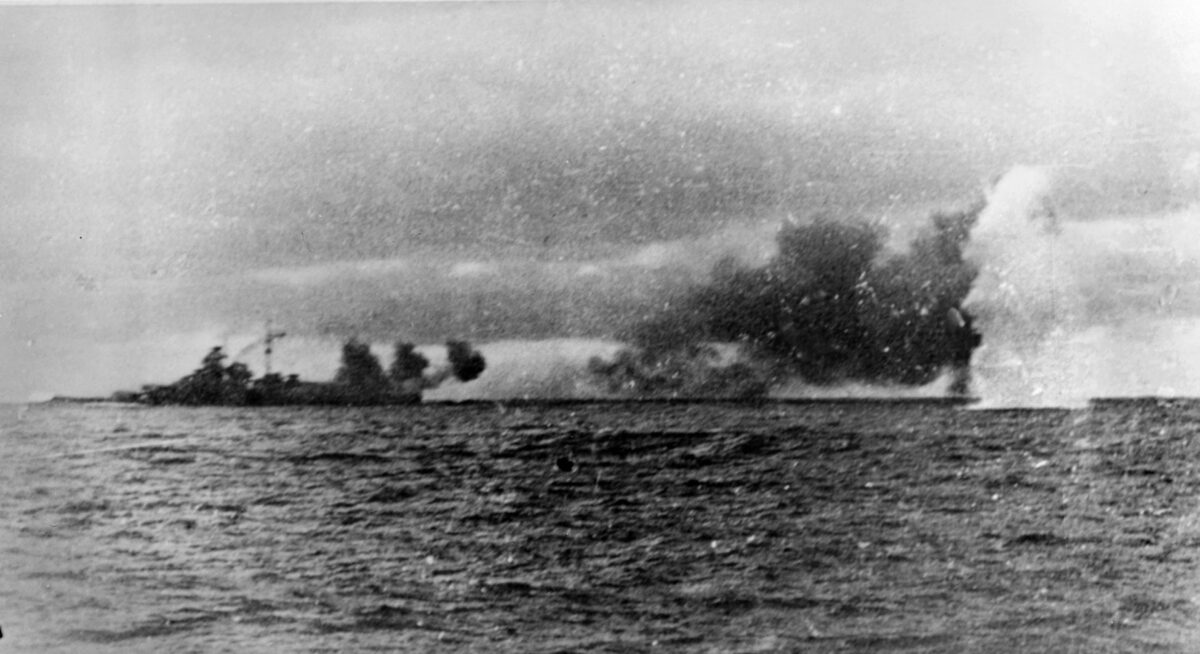

A salvo of Bismarck’s huge 15-inch shells screamed in an unearthly howl from the skies. Hood was straddled by towering columns of water. For a portentous moment, time seemed to freeze; then, the massive warship erupted into a fireball that left only floating debris behind. In those horrifying seconds, the lives of 1,415 British officers and seamen were snuffed out as if they had never existed.

The mighty Hood had blown up. It was the single worst disaster for the Royal Navy in its four centuries of history. Hood was a favorite in Britain, and her loss was a terrible blow to British pride.

It was also Bismarck’s only victory. Three days later, she, too, lay at the bottom of the Atlantic, a victim of German hubris and British vengeance. Ironically, Bismarck sank on the 36th anniversary of Togo’s victory at Tsushima, a date marking both the zenith of the battleship and its final decline.

How could it have happened that the largest and most powerful warship in the Royal Navy was snuffed out in an instant?

The reasons go back to April 13, 1907, when a new warship slid into the waters from the Armstrong-Whitworth Shipyard along the River Tyne in Newcastle, England. The new battle cruiser HMS Invincible was the first in a line of potent warships that would dominate Admiralty doctrine for the next 10 years. Her 560-foot-long hull, displacing more than 17,000 tons, was the height of warship design. When fitted out, Invincible had 30 Yarrow water-tubed boilers conveying high-pressure steam to four modern Parsons Turbine engines that drove four screws to move her sleek hull through the seas at 28 knots.

Her main decks carried four heavy turrets, each mounting two massive 12-inch rifled guns capable of firing shells weighing half a ton over a distance of 12 miles. Without a doubt, Invincible was a radical new concept in capital warship design. But hidden under her bristling guns and gray war paint, Invincible was at serious risk.

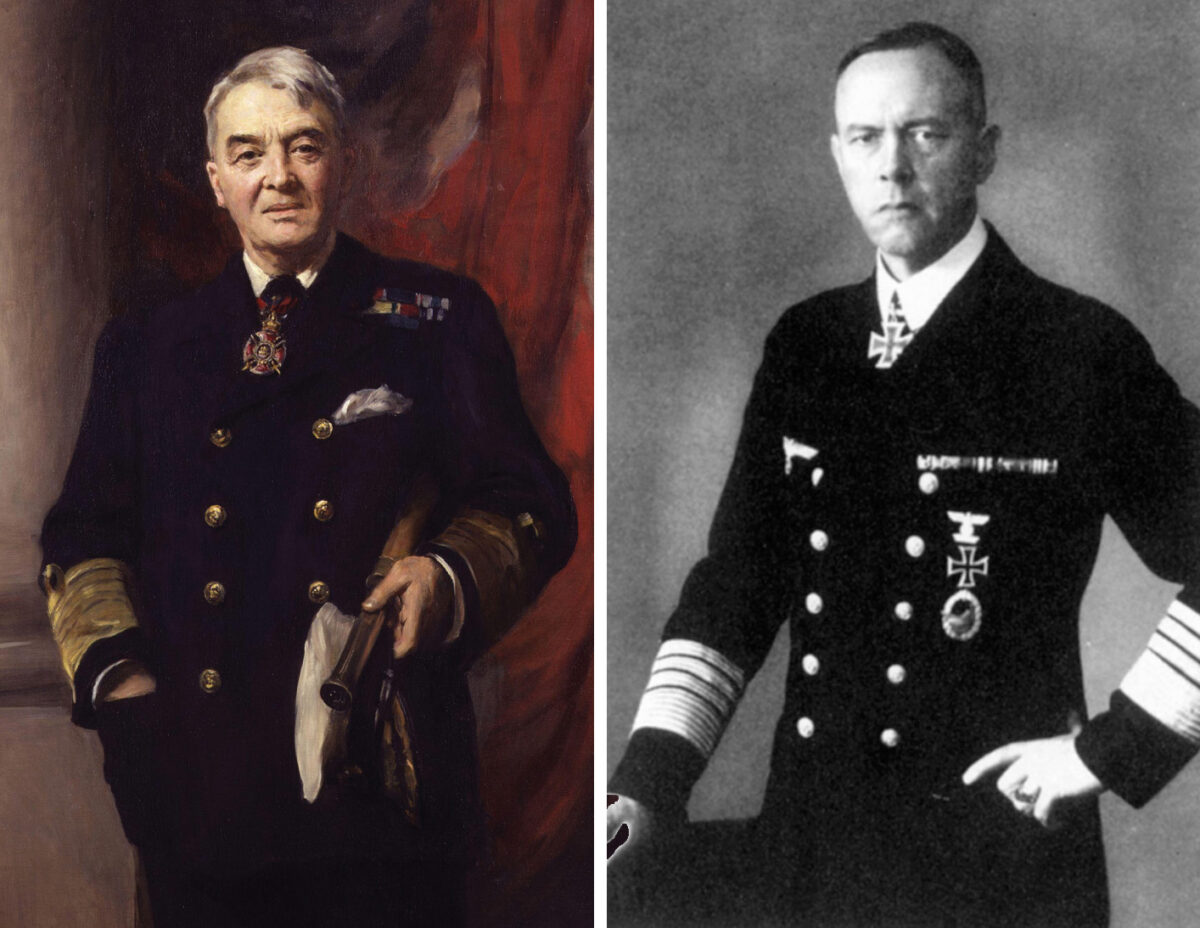

The battle-cruiser concept was first set down by the father of the modern Royal Navy, First Sea Lord Admiral Sir John Arbuthnot “Jacky” Fisher. After ramrodding the innovative, all-big-gun battleship HMS Dreadnought into being in 1906, Fisher developed the idea of fast, heavily armed but lightly armored battle cruisers.

Fisher had decreed that in battle cruisers, “weight in armor should be sacrificed to weight invested in larger guns and heavy propulsion machinery to generate higher speeds.” This became the rule by which all subsequent British battle cruisers were designed and launched.

While there were marked differences in gun caliber, speed, and tonnage, battle cruisers generally had only half the armor thickness around their turret barbettes, hulls, and decks than comparable dreadnoughts in the Grand Fleet. Most dreadnoughts, having more armor, were often 10 knots slower than the big battle cruisers.

In a fast and furious naval engagements over a wide area, as at the Falklands in December 1914, Dogger Bank in January 1915, and Jutland in May 1916, big guns mounted on fast ships could mean the difference between victory and defeat, between survival and annihilation.

Always a proponent of speed and big guns, Fisher knowingly and willingly sacrificed the safety afforded by heavy armor. The battle cruisers, although they could sweep far ahead of the main fleet, move in fast, and engage capital ships at extreme range, were as vulnerable as any light cruiser only half as big. Yet this did not seem to deter or even occur to the Admiralty in 1907.

Fisher’s position and status at the Admiralty was such that no senior naval officer and few government officials could safely challenge him. He wielded immense power and brooked no opposition. Those who unwisely challenged him were buried in his characteristic tsunami of tirades, threats, memos and intimidation.

Even so, there were few men who disagreed with his daring dream of the “super cruiser” or “fast dreadnought.” It was England that led the race to build the fastest big-gun dreadnoughts in the years before and during the Great War. In all, 13 such ships of increasing size and main-gun caliber were constructed after Invincible, eventually culminating with HMS Hood in 1920. Soon Germany, Japan, Russia, France and the United States followed suit, laying down the keels to their own battle cruisers.

But not all the other navies blindly agreed with the Fisher dogma. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who, as Secretary for Naval Affairs, held the same status in the Kaiser’s navy as Fisher in the Admiralty, felt that a warship’s primary job was to remain afloat to fight, and therefore chose to accept lower speed and smaller gun caliber in favor of thicker armor.

The fast battle cruisers were meant to scout far ahead of the main battle fleet, providing information on the enemy’s strength, formation, course and speed. The slower but more heavily armored dreadnoughts were the real power of a navy during the Great War, holding a status that could only be compared to the huge hydrogen bombs of the Cold War two generations later.

And while fast battle cruisers were never intended to engage enemy battleships, their big guns were too tempting for aggressive fleet commanders to discount in a clash of warships.

In addition to thinner armor, they had another fatal flaw. During the Battle of Dogger Bank in the North Sea on January 24, 1915, the SMS Seydlitz, flagship of the German battle-cruiser force, had received a penetrating hit on one of her after-gun turrets. The flash from the explosion went down the barbette to the shell room and powder magazines located below the waterline. Seydlitz was in imminent danger of exploding, but prompt action by an officer flooded the magazine and saved the ship. (The term “barbette” usually means the entire rotating assembly of turret housing, guns, and the vertical trunk extending down into the hull.)

The danger was recognized, and the German Navy began to install double sets of anti-flash doors in the barbettes of every capital ship. Both doors could not be open at the same time, so an explosion in the turret would be stopped before it could reach the powder magazines. The Royal Navy remained blissfully unaware of this same fatal flaw in their own capital ships.

It was at the climactic battle of Jutland a year later that three of Admiral Sir David Beatty’s battle cruisers exploded from exactly this type of catastrophic hit on a turret. After watching the HMS Indefatigable, HMS Queen Mary and HMS Invincible blow up, Beatty said laconically, “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” Fisher’s decree was reaping a deadly harvest. Over 3,000 officers and men died in the three exploding ships.

Jutland also saw an hour-long duel between the heavy dreadnoughts of the German High Seas Fleet and the British Grand Fleet, none of which were lost or seriously damaged. This was undoubtedly due to their thicker armor preventing armor-piercing shells from penetrating the turrets.

In any event, Jutland patently displayed the design fault in the turrets, and changes were made throughout the fleet. Yet Fisher did not recognize or admit that his thin-skinned darlings were literally sitting ducks in a major engagement. After the battle, Fisher, never one to admit culpability, blamed the losses on the Royal Navy commanders and their lack of aggressiveness. “I have worked 30 years to build this fleet and they failed me.”

In only one case did battle cruisers ever make any noteworthy contribution in the war. At the Battle of the Falklands in December 1914, HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible were sent to the South Atlantic to intercept Admiral Maximillian von Spee’s East Asia Squadron, which consisted of two armored cruisers, SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau, and three light cruisers. Only the big guns of the British fast battle cruisers, carried by their great speed, assured victory.

By the end of the war, Fisher had left the Admiralty, still convinced of the value of his dream. In one respect, he had been right: Big guns and speed were essential factors in victory at sea. But the battle cruisers were a doomed hybrid, neither fish nor fowl. They carried big guns but did not dare engage equally armed ships. This was to have tragic consequences for a ship that had yet to be launched while Jutland still dominated the headlines.

Earlier that year, the Admiralty had learned of the proposed German Mackensen-class battle cruisers, which were rumored to be bigger and better-armed than the new British Renown class. They hurriedly laid plans for a new super battle cruiser, the Admiral class.

The losses at Jutland forced the incorporation of thicker armor and anti-flash doors in the turret barbettes. Four keels of the new class were laid down, but only one would be completed. The collapse of the High Seas Fleet and the imminent end of the war convinced the Admiralty that the money for the other three ships could be better spent rebuilding Britain’s merchant fleet, which had been decimated by U-boats.

Only one, therefore, of the mighty Admiral-class ships was launched and commissioned. The contract for the new warship was awarded to the John Brown Shipyards in Clydebank, Scotland, in April 1916. Her keel was laid down in September, and her massive hull slid into the River Clyde on August 22, 1918, less than three months before the Armistice.

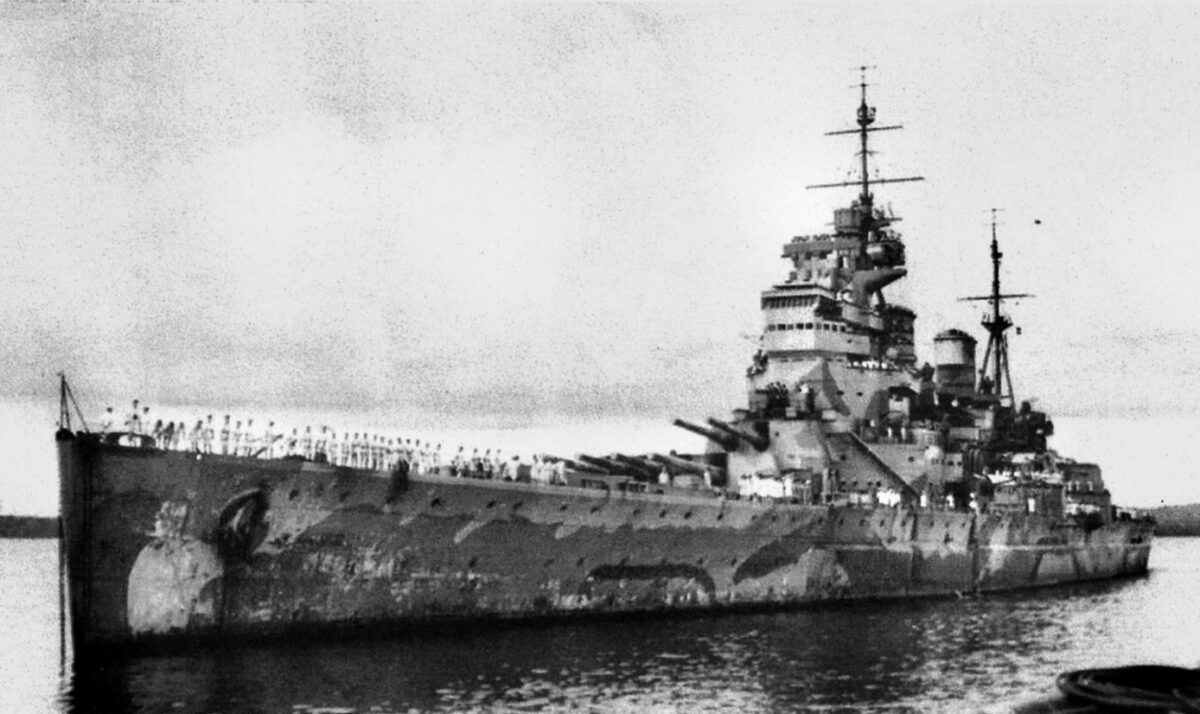

HMS Hood, named for the 18th-century Admiral Samuel Hood, was the first capital ship to be commissioned after the war ended. Her hull was constructed on the same slipways where the liners Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth would be built in the 1930s.

Hood’s motto was “Ventis Secundis”—Latin for “With a Favorable Wind.” From the start, Hood became a national favorite. The largest and most powerful warship in the fleet, she carried four main gun turrets, each mounting twin 15-inch Mark I rifles, capable of firing 1,900-pound armor-piercing shells to a maximum range of 30,000 yards. The four turrets, two forward and two aft, were designated “A,” “B,” “X,” and “Y.” The magazines for each turret held 240 powder charges and shells. Her 860-foot hull was 104 feet wide at the widest point.

Drawing more than 30 feet, her hull, deck, and barbette armor were heavier and thicker than that of any previous battle cruiser. She was more than 100 feet longer, 20 feet wider, and 13,000 tons heavier than the largest battle cruisers in the Royal Navy.

Initially, Hood displaced 42,300 tons, but the later installation of more armor increased her displacement to 45,000 tons; this made Hood ride four feet deeper in the water. In even moderately heavy seas, the waves rode over her bows and across the deck, earning her the dubious reputation as “the largest submarine in the British Navy.”

In 1939 and 1940, her original 5.5-inch secondary armament was replaced with more efficient Mk XVI twin-mount, dual-purpose 4.1-inch guns, each of which had its own magazine holding 200 shells. Hood had four fixed 21-inch tubes for her 28 torpedoes, fitted above the waterline aft of the rear funnel.

Twenty-four Yarrow boilers fed steam to the four huge Brown-Curtiss geared turbines, with a total of 144,000 shaft horsepower. This drove the Hood through the water at an impressive 31 knots, better than any of Fisher’s vaunted wartime fast battle cruisers.

Hood’s armor along the hull and the turret barbettes was adequate to protect against armor-piercing shells from a low trajectory, but she remained vulnerable to plunging shells and bombs on her decks and turret roofs. This aspect of Hood’s vulnerability was never fully addressed.

In fact, her popularity and stature in the Royal Navy was a detriment to any modernization or improvements that would have added to her survivability. In 1941, Hood had no more armor protection than she had been given in 1918.

Her armor was adequate for what the German Navy might have unleashed on her in the Great War, but it was too light for the later generation of high-trajectory, high-velocity, armor-piercing rounds coming into use by the end of the 1930s.

With that in mind, the Admiralty decreed that Hood was not to be part of the main fleet, but was instead to operate in the classic battle cruiser role of fast scout. This was her primary duty in the years before World War II.

In the early 1930s, in shipyards across the North Sea, Germany had been violating the terms of the Treaty of Versailles by constructing a series of ever-larger surface warships. Curiously, from the heavy cruisers to the so-called “Pocket Battleships” to the titanic dreadnoughts launched in 1939 and 1940, there was not a fast battle cruiser among them. While they differed greatly in size, gun caliber, and configuration, the Third Reich’s big warships were fast, powerful, and clad in heavy protective armor.

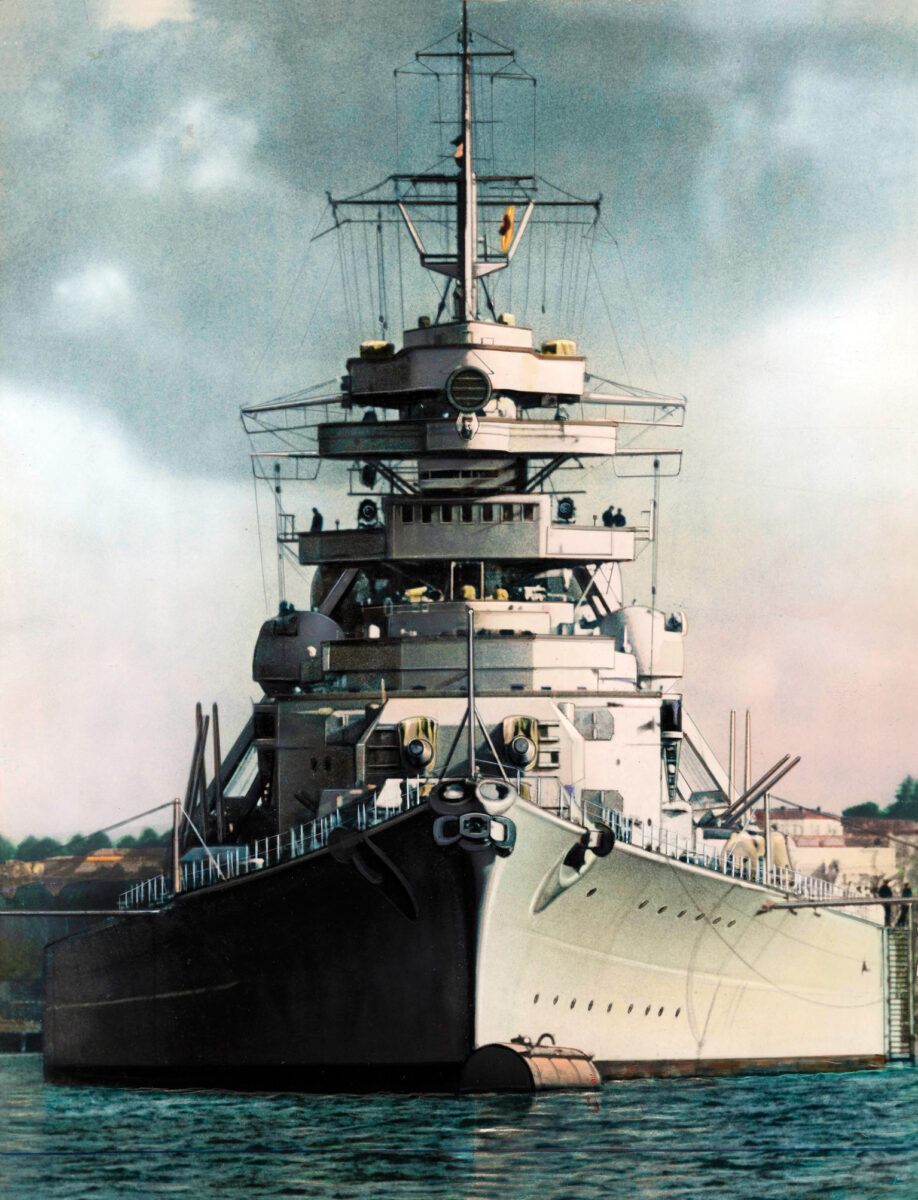

The biggest and most modern of them were the sister battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz. Bismarck was launched in Hamburg on St. Valentine’s Day 1939, with Adolf Hitler himself watching. And while she was erroneously touted in the Nazi press as the most powerful warship afloat, Bismarck was certainly the largest and most advanced warship ever constructed in Germany.

The British Admiralty watched with trepidation as the new battleship finished her sea trials in the Baltic in 1941. By then, most of the surface raiders had either been sunk, damaged, or forced into port. The huge Bismarck was a dangerous threat to the many vital Allied convoys in the Atlantic. She would have to be stopped at all cost. But Bismarck was faster than any battleship in the Royal Navy. So the Admiralty sent the only two capital ships capable of catching and stopping Bismarck: Hood and Prince of Wales.

But while the two largest combatants were almost equally armed with eight 15-inch guns in four turrets, the scale was vastly tipped in the German warship’s favor.

Displacing over 50,000 tons fully loaded and with a hull 798 feet long, Bismarck had a beam of 118 feet. This made her heavier and wider than Hood and reflected the differing views of the German Navy’s philosophy about armor.

Her 12 Wagner high-pressure boilers drove the three-geared turbine’s 148,000-horsepower shaft. Although Bismarck displaced 5,000 tons more than her British opponent, she still nearly matched Hood’s 30-knot speed.

Bismarck’s armor protection was even more impressive. A belt over 12 inches in thickness girded her hull while 14 inches clad the four main gun turrets and barbettes. Additionally, German armor was far superior in tensile strength than that used in Britain. Bismarck’s armor constituted over 40 percent of her total displacement, as opposed to the 30 percent on Hood.

From a purely aesthetic standpoint, Bismarck’s design reflected the more modern designs of the 1930s. From her raked Atlantic clipper bow to the smooth curves of the hull to the curving cruiser stern, the German ship was undoubtedly more pleasing to the eye than the angular silhouettes of most British warships.

But it was in radar and fire control that Bismarck’s real advantage rested. Being a generation newer than Hood, Bismarck was equipped with three FUMO-23 search- radar units. With direct input to the main fire-control stations, these sets allowed Bismarck to quickly fix the range of an enemy vessel. Hood was also fitted with fire-control radar, but her maneuvers in the fateful battle would negate their effective use.

Hood’s only advantage was in the mass of her armor-piercing projectiles, which weighed 1,900 pounds as compared to her opponent’s 1,800-pound shells. With these heavier shells, Hood’s 29,000-yard effective range was 6,000 yards less than Bismarck’s.

We must examine the actual circumstances of the events of that morning in order to determine how Hood died. The Denmark Strait, a wide northeast-to-southwest channel that separates Greenland from Iceland, was where Bismarck and her smaller consort, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, were making their break for the open Atlantic.

The Royal Navy had two light cruisers, HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk, patrolling in the strait to shadow the two German warships until the venerable Hood and her brand-new companion, the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, could arrive. There was little doubt in the minds of the British that Hood, being the most powerful warship in the fleet, could easily take care of Bismarck.

During the night, Bismarck, which had been in the lead, had fired on the Suffolk and Norfolk in an attempt to sink or disable them. Five salvoes of 15-inch shells rained down on the smaller, rapidly twisting ships without hitting them.

But Bismarck’s FUMO-23 fire-control radar was damaged by the concussion of her guns, and Admiral Günther Lütjens ordered the cruiser Prinz Eugen to take station in the lead with her own functioning radar. Thus, it was Prinz Eugen in the lead when dawn approached on May 24.

When the British and German squadrons first sighted each other at 5:30 AM, the distance was 28,000 yards (15.8 miles), which put them on each other’s horizon. Hood, being initially southeast of Bismarck, was silhouetted against the dawn sky, while the Germans were still lost in the gloom. This gave the Germans the initial advantage.

Commanded by Vice Adm. Lancelot Holland, Hood and Prince of Wales opened fire at extreme range, but because the Prinz Eugen had nearly the same silhouette as Bismarck and was in the lead, Holland initially concentrated Hood’s fire on the cruiser.

Both German ships aimed at the distinctive shape of the Hood, which was ahead of the Prince of Wales. Instead of relying on radar, the German fire control was initially directed by the excellent rangefinders high on Bismarck’s superstructure.

Hood’s first salvo, fired at a range of 25,000 yards (14.2 miles) at 5:52 AM, fell short. Holland, realizing they needed to get closer, ordered a 20-degree starboard turn to the northwest to bring the two Royal Navy warships closer to Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. Well aware of his flagship’s vulnerability to plunging fire, Holland also wanted to force the Germans to lower their guns so their fire would be on a flatter trajectory. Thus, the shells would hit Hood’s thicker side armor.

But the turn towards the Germans masked the three after turrets of the Prince of Wales and Hood, depriving them of nearly half their firepower in the opening stage of the battle.

On Bismarck’s bridge, Admiral Lütjens ordered Captain Ernst Lindemann to open fire on Hood at 5:55 AM. On Hood, Holland saw the bright flashes of Bismarck’s eight heavy guns. A few seconds later he heard a roar like a speeding freight train as the huge shells screamed overhead and hit the water. Tall white waterspouts towered as high as Hood’s foretop.

A sudden sharp shudder shook the 45,000-ton warship. Hood had been hit. Prinz Eugen added her eight smaller guns to the deadly duel, but did little damage. Still, the old battle cruiser bored in, her guns reaching out to her distant enemy. Again the flashes, and again the roar of heavy shells tore over Hood.

With their advanced fire-control systems, the two German ships were able to loose four broadsides at the British. Prince of Wales, being fresh out of the builder’s yards, was unable to get all her guns firing, and Hood was only able to use her fore turrets. The range had closed to 16,500 yards (9.3 miles) when Holland ordered a turn 20 degrees to port, thus unmasking “X” and “Y” turrets.

It was now 5:56 AM. A shell from Bismarck’s fifth salvo crashed through Hood’s afterdeck near the mainmast. That was the killing blow.

A thunderous eruption of flame, steam, smoke, and flying debris instantly smothered the place where the mighty Hood had been. The sound of her destruction roared over the cold waters of the Denmark Strait and echoed off the distant icy shore of Greenland.

Three minutes later Hood was gone, her torn remains settling onto the frigid black sea floor 9,000 feet below. From her crew of more than 1,400, only three survivors were picked from the freezing water.

The first public announcement from the Admiralty on May 24 reported that “HMS Hood received an unlucky hit in a magazine and blew up.”

In two best-selling books by C.S. Forester and William L. Shirer, the descriptions of how Hood died have become the stuff of seafaring folklore. According to both books, the Hood had what was euphemistically called a “chink” in her deck armor on the boat deck between the two funnels. A 15-inch armor-piercing shell struck exactly at this spot at 5:56 AM and penetrated six decks and six bulkheads to explode in the main powder magazine, igniting 300 tons of high-explosive cordite. Several jets of flame and smoke burst from her superstructure, and a huge sheet of fire rose between the funnels to a height of a thousand feet. A massive gray cloud cleared and revealed the bow and stern of Hood jutting out of the water like “two sharks until they sank.”

These accounts have long been accepted by the general public, but they fall short in two major areas: there was no so-called “chink” in Hood’s deck armor, and there was no main gun magazine in that area to destroy Hood. The two forward and two after gun barbettes were separated by nearly 400 feet. The intervening space under the funnels was taken up by the 24 Yarrow boilers and their uptakes.

So the question remains: how could it happen?

The only logical culprit had to be Hood’s lack of sufficient armor protection. When Hood was first designed in 1916, she was to be larger, faster, and more heavily armed than the biggest battle cruiser ever built up to that time. But Fisher’s old refrain of a fast, heavily armed, and lightly armored ship still held sway, and Hood’s armor was significantly thinner than that of a battleship of comparable size, even after her 1939 and 1940 refits.

The numbers leave little doubt. In 1941, Hood’s main protection was along her hull to prevent penetration from heavy shells and torpedoes. The belt ranged from six inches thick at the bow and stern to 12 inches along the most vulnerable areas, such as the magazines and boilers.

The barbettes—the main structures of the turret assemblies—were sheathed in 12 inches of steel. The turret housings, the part that actually enclosed the guns, had 15 inches of armor on the front, which was intended to face the enemy warships, and 11 inches on the sides and rear. Yet, despite the hard lessons of Jutland, Hood’s turret-roof armor was only five inches in thickness—an inch thinner than the thickest deck- armor plating.

While this might seem adequate, consider that a battleship of the same era usually had hull and deck plating that ran between 12 and 15 inches in thickness. This would stop or deflect the heaviest armor-piercing shells then in use.

There is no evidence that any of Bismarck’s shells penetrated Hood’s barbettes in those three minutes of battle. Rather, it is well-established that the fatal blow struck somewhere amidships in a manner that managed to convey the detonation to one of the battle cruiser’s after-powder magazines, which were located six decks down in the very bowels of the vessel.

Considering her size, this bears closer examination. In the Great War, a dreadnaught’s fire was directed visually from rangefinders in the foretop high over the superstructure, and most naval battles were fought at ranges of less than 15,000 yards (nine miles). But the advent of radar for fire control made it possible to fight naval engagements at ranges of more than 25,000 to 30,000 yards, (14.2 to 17.0 miles), often far beyond visual range.

Main gun turrets could elevate the guns as high as 30 degrees, which imparted a high-arc trajectory to the shell, which then plunged downward into the decks of enemy ships. But Hood’s deck armor was only two inches thick at the bow and stern, and increased in thickness to just over six inches on both the main and boat decks.

Accounts from witnesses on the light cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk and survivors from Bismarck described the cataclysm. To the majority of witnesses, the explosion was amidships near the funnels. Hood’s after-portion seemed to break away from the main hull and sank first. Apparently one or more of the magazines had exploded in the after-portion of the hull.

With the exception of Prince of Wales, all other ships viewed Hood from either port or starboard. The new battleship, being aft of Hood, had a view that revealed what really happened. Captain John C. Leach on Prince of Wales’ bridge later described the column of flame shooting up from the vicinity of Hood’s mainmast, which was on the after-portion of the boat deck and just forward of “X” turret. He said the blast obscured and then obliterated the entire after portion of Hood. While there were no main guns on the amidships superstructure, it did contain the 12 twin-mount 4.1-inch guns, each of which had its own magazine with 200 shells.

The official board of inquiry report, released on June 2, 1941, stated, “…the probable cause of the loss of HMS Hood was direct penetration of the protection by one or more 15-inch shells at a range of 16,500 yards, resulting in the explosion of one or more of the aft magazines.”

While the findings were straightforward, they almost immediately came under criticism. The circumstances of the battle and its aftermath meant that there were no immediate verbatim statements taken from any of the witnesses, neither British nor German.

Then other theories emerged, including one in which Hood had been destroyed by the internal detonation of her own torpedoes, located in the hull aft of the rear funnel. Hood did carry 28 torpedoes, theoretically more than enough to destroy her. But from the start, there was good reason to discount this theory, and it was never given much credence.

A second inquiry, held in September 1941, taking into evidence the testimony of over 100 witnesses, was more thorough, but came to much the same conclusion: Hood died from an explosion in either her 4.1-inch or 15-inch after-magazines.

The most likely probability was that the 4.1-inch magazines, located closer to the mainmast, exploded first, starting an instantaneous chain of explosions in the larger magazine. This seems to fit the eyewitness accounts. If a shell had penetrated at this point, it could have started an intense fire in the engine room that tore through the ventilators into the after-powder magazines.

Another element that supports this position was the multiple eruptions of smoke and fire—witnessed by Captain Leach and surviving Germans—that seemed to shoot up from the engine-room vents. The engine rooms were located aft of the boilers on either side of the barbettes and magazines. If an explosion in the after 4.1-inch magazines or the boiler rooms occurred, the blast would almost certainly have destroyed the bulkheads, which were only four inches thick.

The original long-accepted view of a “chink” in the deck armor allowing a shell to explode the magazines must be addressed. When Hood exploded, the combatants were about 16,000 yards apart, which meant that Bismarck would have had her guns elevated to about 14 degrees. This made the shells’ trajectory nearly flat. Any shell coming in from an angle of 14 degrees could not have reached Hood’s after-magazines without first penetrating the 12-inch hull armor belt.

While a so-called weak spot might have allowed a shell to enter the superstructure, it would not have gone downwards. At most, it would have torn across the width of the superstructure. Of course, this is where the 4.1-inch barbettes were located, with their corresponding magazines just below.

One theory involved a report from Prince of Wales that “unusual discharges” were coming from one of Hood’s forward guns. This testimony was taken at the second inquiry, and it promped the suggestion that Hood had suffered a Jutland-type of explosion following a flash fire in a forward magazine. But the fact that it was the battle cruiser’s after-portion that was the center of the large explosion seems to refute this theory. Also, Hood’s bow would have been extremely difficult for anyone on the following battleship to see clearly.

The 2001 discovery and exploration of Hood’s watery grave revealed how violent the explosion had been. She lies in 9,200 feet of water, with her remains scattered across three distinct debris fields. The large midsection is overturned, while the stern is several hundred feet away. The bow and superstructure are likewise separate from the main section. The wide gap between the main hull and stern proves conclusively that the magazines for either “X” or “Y” turrets did explode. The hull broke apart on the surface.

The rudder is still set at port, exactly where Holland had ordered it just before the fatal blow. Curiously, Hood’s bow is gone just forward of “A” turret. One clue as to the reason for this may be found in a hit on Prince of Wales, which was taken under fire by Bismarck after the destruction of Hood. A 15-inch shell fell short and slid into the water 80 feet off her side and penetrated the hull 30 feet below the waterline beneath the armor belt. It tore into the warren of compartments and bulkheads but failed to explode.

This could conceivably also have happened to Hood. One shell might have struck the water off her starboard quarter and exploded in the after-powder magazine. The wreck reveals that nearly the entire starboard hull in the region of the fuel-oil tanks has been torn open from an internal explosion. If a shell did penetrate and explode under the waterline, it could have ignited the fuel from stern to bow and possibly been responsible for blowing off Hood’s bow, as well as igniting the aft magazines.

Obviously, there are many theories and explanations for the sinking of Hood. But using Occam’s razor, the most likely cause was a hit in or near one of the 4.1-inch magazines, which then, either directly or via the engine room, reached the 150 tons of cordite in the handling room of the after turrets. At that point, the blast erupted upwards through the ventilators and hatches that dotted the boat deck and superstructure, creating the “sheet of flame and smoke” described by so many witnesses. That blast obscured what was happening as the entire after-portion of the hull tore open and fell away.

In any event, the explosion that killed Hood and over 1,400 men was almost certainly the result of the same type of blasts that sank three British battle cruisers at Jutland almost exactly 25 years earlier.

There lies the mighty Hood, 150 fathoms down in a black, icy grave, the last monument to Jacky Fisher’s flawed dream of the fast battle cruiser.

Despite the Battle of the Denmark Strait and the sinking of Bismarck being one of the most famous naval engagements in history, it played virtually no role in the Battle of the Atlantic or the outcome of the war. The primacy of the battleship had reached its apogee at Tsushuma. Never again would the big-gun warship play a significant role in the fate of wars and nations.

This was dramatically proven in late 1941, when HMS Prince of Wales, along with the battle cruiser HMS Repulse, were sent to the Pacific to protect British interests in Singapore. On December 10, both warships were sunk with absurd ease by Japanese land-based aircraft using bombs and torpedoes. Even Prince of Wales’ heavier armor was not enough to protect her from Japanese air attack.

But a new concept, unheard of in 1907 when Invincible slid into the water, was beginning to appear on the seas in the late 1920s. Due to the limitations of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, three of Britain’s smaller battle cruisers, HMS Courageous, HMS Furious and HMS Glorious, were converted into aircraft carriers. The United States followed suit by converting its last two battle-cruiser hulls into the aircraft carriers USS Lexington and USS Saratoga.

Ironically, the speed of the fast battle cruiser, as envisioned by Fisher, was critical to making them effective aircraft carriers. The big-gun warship had reached and passed its apogee and was soon to become a supporting element to the carrier.

Side note: The loss of the Hood, a battle cruiser with lighter armor in favor of speed, was at least partially attributed to the British not having learned from the Battle of Jutland in 1916 that skimping on armor was not a good move. The British got a repeat lesson in Dec 1941 with the loss of battleship Prince of Wales and battle cruiser Repulse off Singapore. While Hood was lost to gunfire, Repulse and Prince of Wales were lost to land based aircraft. Neither of the two capital ships was able to support the other in fighting off aircraft and thus both were lost. It was not until the battle of Taranto in 1940 that it became apparent ships needed protection against sea and air attack. A full year later, ship defense had still not been fully protected against air attack. American ships had increased anti-aircraft guns installed as upgrades after Midway and on new construction. The US Navy had never adopted the battle cruiser and thus lost no battleships after Pearl Harbor.