By Michael D. Hull

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Travers Harris, the burly, red-haired chief of Royal Air Force Bomber Command, was an anxious man on the evening of Saturday, May 30, 1942.

Attending a late dinner party in Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s weekend retreat at the leafy Chequers estate in Buckinghamshire, Harris expounded on the need for the long-range, strategic bombing of Germany. Besides the premier, his listeners included General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces. Forward elements of his Eighth Air Force were then assembling in England to join the RAF’s aerial offensive against Nazi-occupied Europe.

“Bomber” Harris enjoyed the full backing of the prime minister, who had declared in 1941, “When I look round to see how we can win the war, I see that there is only one sure path. We have no continental army which can defeat the German military power. There is one thing that will bring Hitler down, and this is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland.” Dishing out some of the same death and destruction which enemy planes had wrought on Britain for two years, Harris had complied by initiating relentless nighttime raids on German industrial centers and cities. Daylight sorties had proved too costly.

Like his American colleagues, Arnold and Generals Carl A. Spaatz and Ira C. Eaker, Harris believed naively that a round-the-clock strategic bombing offensive would bring Germany to its knees without the need for a major ground campaign in Europe.

Now, on the evening of May 30, 1942, the resolute, blunt-spoken air marshal was ready with a major gamble to dramatize his crusade and convince pacifist doubters by launching Operation Millennium, the biggest and most daring air raid ever attempted. Bomber Command’s first-line strength amounted to only 416 aircraft that month, but by using second-line and training squadrons, Harris was able to line up 1,046 bombers for an attack against the historic city of Cologne on the west bank of the River Rhine on the night of May 30-31. The principal objective of World War II’s first 1,000-plane raid was the city’s chemical and machine-tool industries.

The striking force comprised 598 twin-engine workhorse Vickers Wellingtons, 131 four-engine Handley Page Halifaxes, 88 Short Stirlings (the first Allied four-engine bombers to see service in World War II), 79 twin-engine Handley Page Hampdens, 73 four-engine Avro Lancasters, 46 twin-engine Avro Manchesters, and 28 obsolete twin-engine Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys. The future of Bomber Command and the growing Allied aerial offensive rested upon the mission’s success or failure.

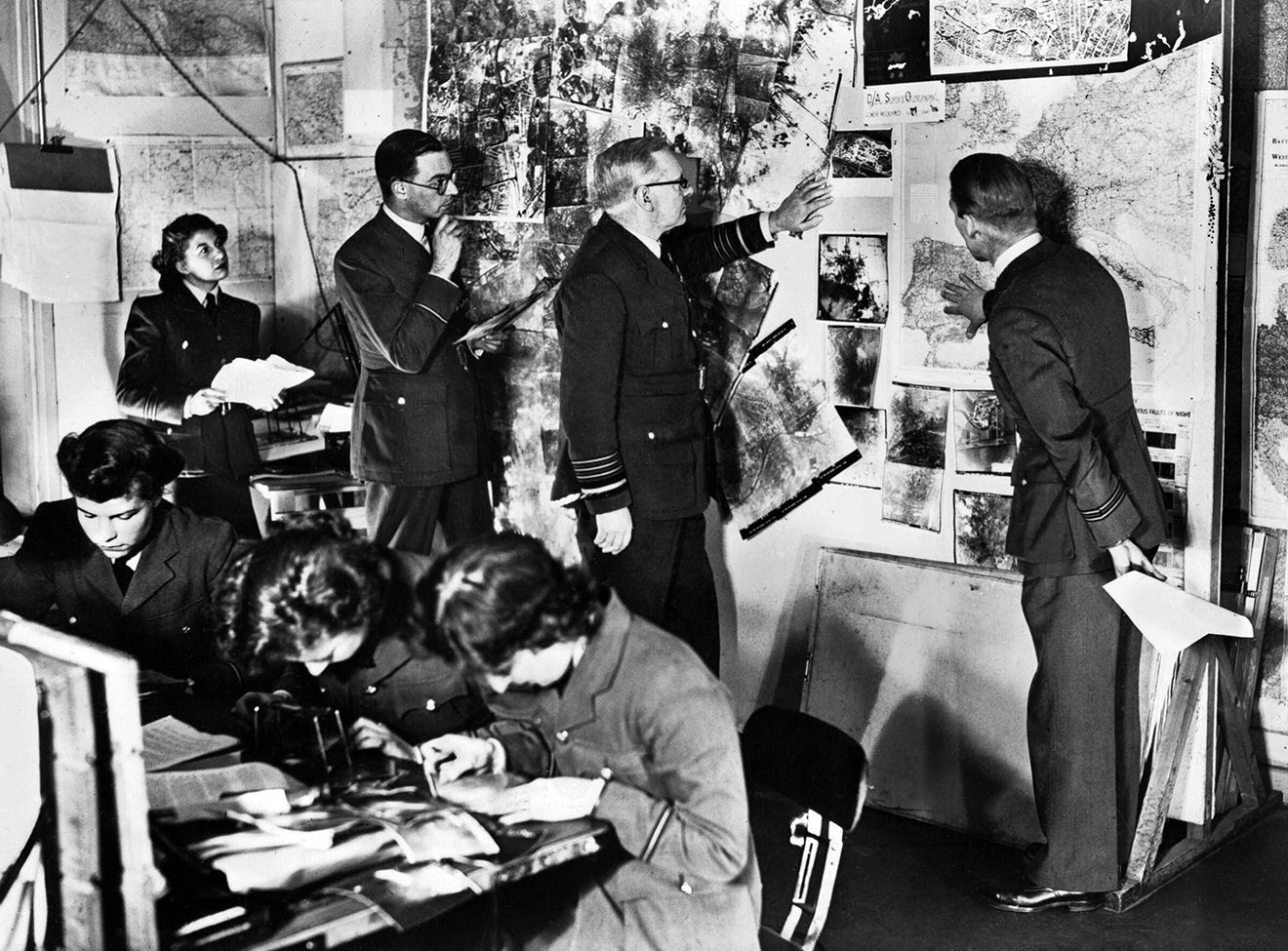

Postponed twice because of bad weather, the complex operation had been meticulously planned by Harris; his pudgy, mustached deputy, Air Marshal Sir Robert Saundby; and their staffs. Ground crews worked around the clock, and the morale of the flight personnel was high. Churchill asked Harris, “How many are you going to lose?” The air marshal replied, “Say 50 aircraft and crews.” The premier responded, “I’ll be prepared for the loss of 100.” Harris was sure that he could keep the losses to five percent or lower by concentrating an unbroken stream of bombers over the target for 90 minutes.

During their final briefings after teatime that Saturday, the Millennium air crews listened to a message from Harris. “The force of which you form a part tonight is at least twice the size and has more than four times the carrying capacity of the largest air force ever before concentrated on one objective,” he wrote. “You have an opportunity, therefore, to strike a blow at the enemy which will resound not only throughout Germany, but throughout the world…. Let him have it—right on the chin.” Churchill added, “This proof of the growing power of the British bomber force is also the herald of what Germany will receive, city by city, from now on.”

Hearing a clock chime at 10:30 that evening, Harris glanced briefly at his watch. His thoughts went to the 53 airfields scattered across Lincolnshire, Yorkshire, and East Anglia where bomber engines were coughing into life as 6,000 of his young pilots, navigators, and gunners nervously waited for takeoff signals. They formed the largest air armada in history.

Weather conditions, a concern until the last minute, “had absolute power to make or mar an operation,” said Harris. “If I waited,” he added, “I might have to keep this very large force standing idle for some time, and I might lose the good weather over England. To land such a force in difficult weather would at that time have been to court disaster.” But the latest report on May 30 said that while the clouds were thick over Germany, there was a 50-50 chance that the sky would be clear over Cologne by midnight. Harris was not enthusiastic about this, but there would not be a full moon for a month. He did not wish to wait that long.

Takeoff signals flashed at 10:30 on the fateful Saturday night, and the first wave of incendiary-laden Wellington “Wimpys” and big Stirlings of the pathfinder squadrons lifted from the runways. They were followed at precise intervals by the main force. Carrying maximum loads of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, the planes thundered across the North Sea above a blanket of moonlit clouds. More than 100 bombers were forced by icing or mechanical problems to turn back, but the rest streamed on eastward over the Dutch coast toward Germany. There was no letup in the thick clouds for an hour.

The RAF pilots and crews peered tensely for signs of interception as they flew through German air space, but the night fighters of Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe steered clear of the mighty armada. As the pathfinders approached Cologne, they could see that the cloud cover had dissipated. Only a few cirrus wisps drifted over the city, and the shimmering Rhine and 500-foot-tall twin spires of the city’s famous 13th-century cathedral glistened in bright moonlight. The visibility was good.

Flying at 15,000 feet, the first two Stirlings headed for their aiming point in the city’s old Neumarket section. It was 12:47 a.m. on Sunday, May 31, and the British bombers were eight minutes ahead of schedule. Cologne, which had been the target of 1,346 RAF sorties in the previous nine months, was quickly alerted. An air-raid warning had sounded, most of the city’s 800,000 citizens had taken shelter, and fire-brigade squads were standing by.

Five hundred antiaircraft batteries surrounding the city spat fire at the vanguard formation, but the Stirlings and Wellingtons flew undeterred through the shell bursts and started their runs. Bomb-bay doors swung open, and 20-pound and four-pound incendiaries showered on the blacked-out city. Fires broke out immediately and spread.

As the leading bombers wheeled and started back for England, their crewmen saw unrelated fires springing up on the outskirts of the city in an attempt by the Germans to confuse the following planes about the true aiming point. But the bombers kept coming, threading their way through the blue-white glare of 150 powerful searchlight beams and salvoes from deadly 88mm flak guns. The bombs fell, and so did 16 planes and their crews. Another four were shot down by enemy fighters. A total of 40 bombers were lost during the raid.

Many areas of Cologne were soon ablaze as the relentless formations of bombers dropped their deadly loads. When the main body of Harris’s force drew near, it appeared to the surprised crews that the whole city was alight. Bombardiers peered down to detect unburned sections before releasing their high explosives and incendiaries. The fires continued to spread, acting as beacons for incoming bombers, and the glows from some large blazes were visible 150 miles away. Cologne was an inferno.

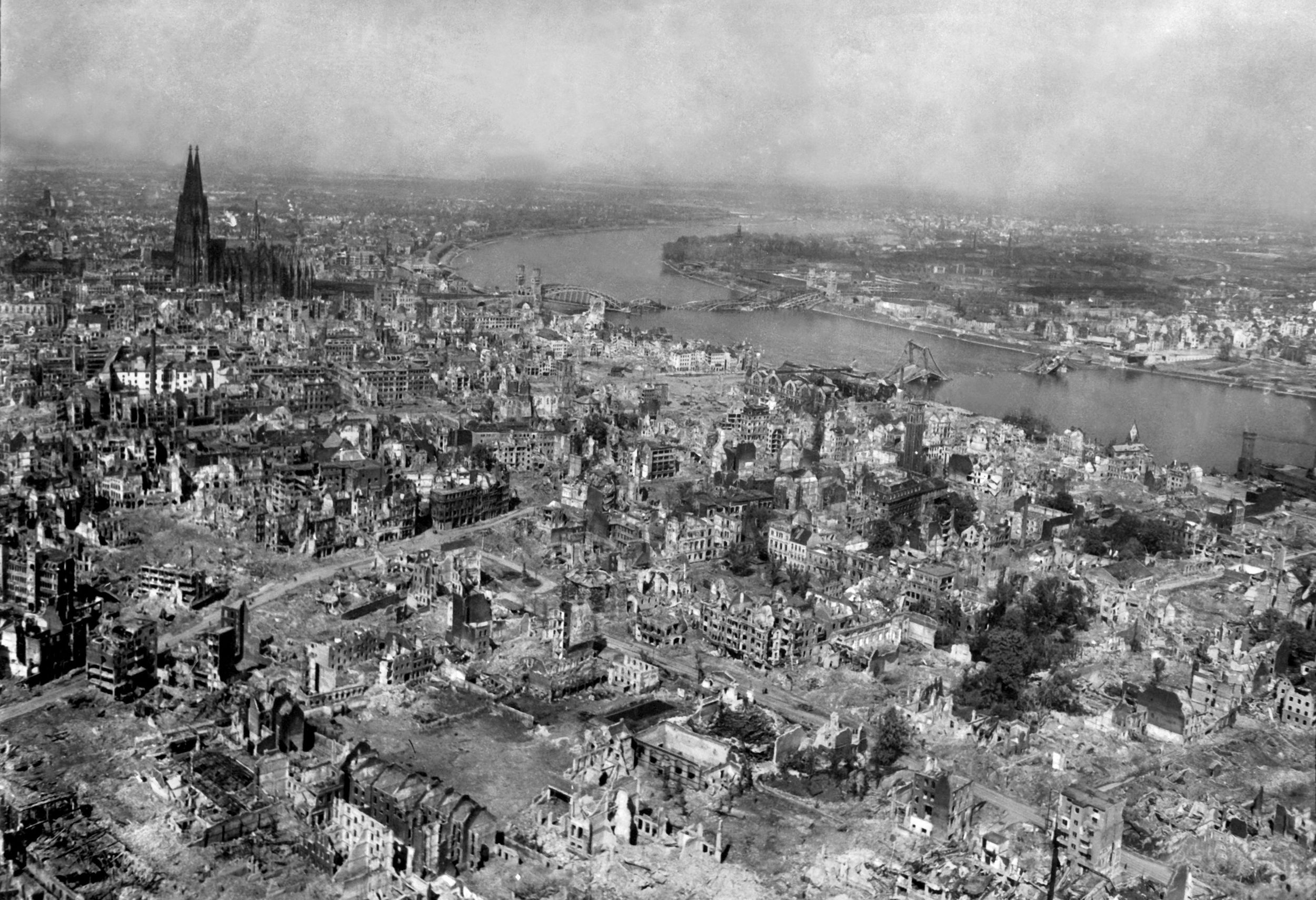

Stores, factories, office buildings, and many churches were leveled, and 3,330 houses were destroyed and 9,510 damaged. An estimated 45,152 people were left homeless. Six hundred acres of the city were devastated, but the cathedral’s landmark twin spires still stood. The death toll was 474, and more than 5,000 citizens were injured, though only 565 required hospital treatment.

Operation Millennium’s Sunday punch was delivered by more than 200 Lancasters and Halifaxes carrying 4,000-pound bombs. The plan called for the last bomber to be over the target no later than 2:25 a.m. on May 31, but stragglers—delayed by having to break formation to avoid antiaircraft bursts and collisions—still came on. The last bomb was dropped from a Lancaster at 3:05 am. The 898 bombers that reached and attacked Cologne dropped a total of 1,500 tons of bombs, two-thirds of which were incendiaries.

After devastating the city, the British bombers fought their way back to England. Although they were set upon by swarms of Messerschmitt Me-109 and Me-110 fighters, most of them managed to touch down at their bases. The crews turned in optimistic reports at their debriefings, but the success of the mission could not be fully evaluated until daylight reconnaissance photographs were available from Bomber Command’s long-range De Havilland Mosquito fighters.

At dawn on May 31, one of the Mosquitoes reported a great pall of smoke over Cologne, with many fires still burning and “heavy and widespread damage.” The bombs and incendiaries also took a toll on the city’s industry. Thirty-six factories were crippled, and another 70 had their output halved. Yet only one month’s war production was lost. Displaying the same stoicism that British civilians had shown in London, Coventry, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bristol, and Plymouth in 1940-41, the people of Germany’s fifth-largest city took swift measures toward recovery.

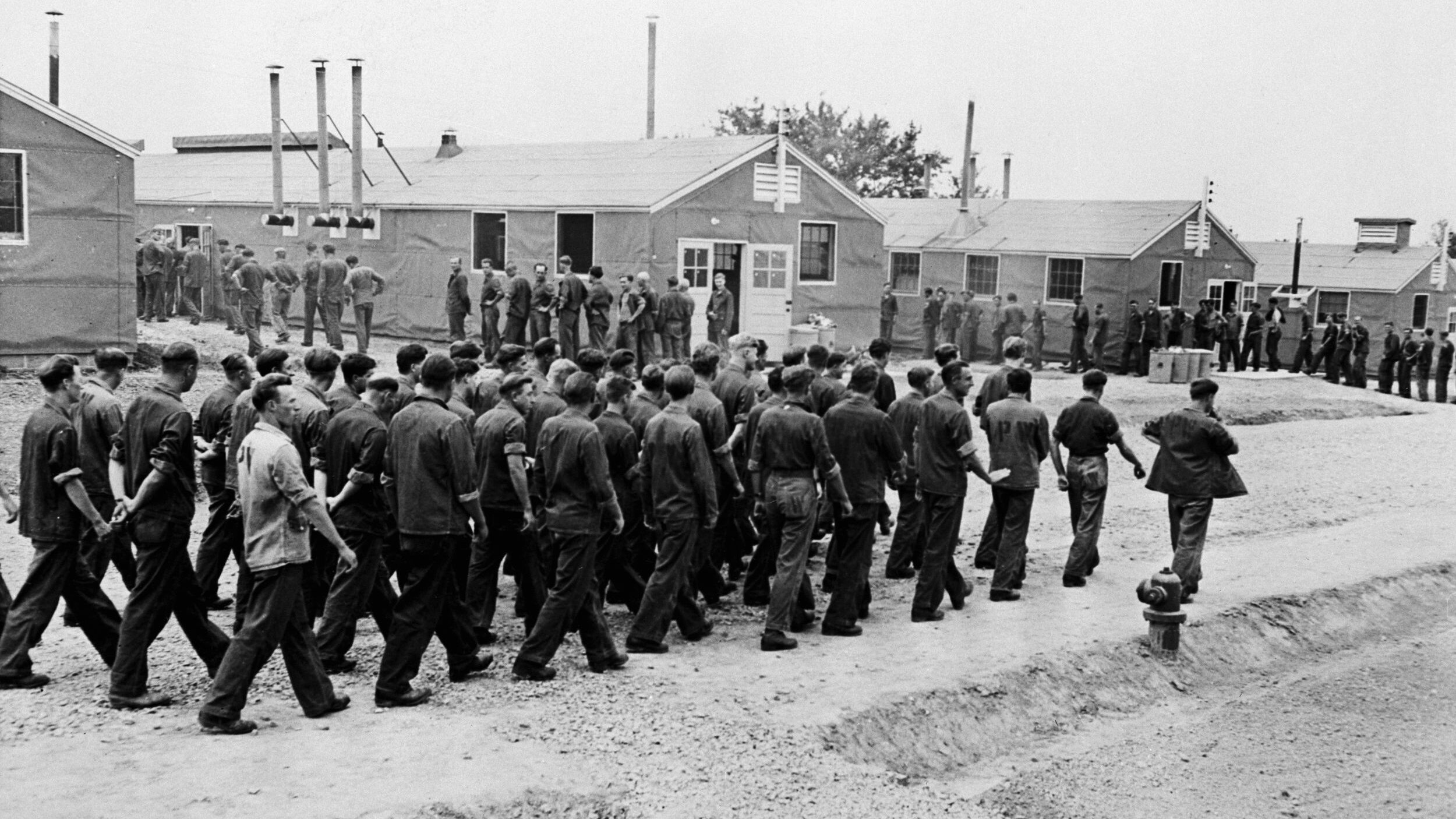

The bombing of Cologne—the first great air raid of the war—stunned the German high command. Albert Speer, the war production minister, disbelieved the initial reports, and when Reichsmarshal Goering received a telephone call the following day from the city’s gauleiter, he ranted, “Impossible! That many bombs cannot be dropped on a single night. The report from your police commissioner is a stinking lie!” Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, who had said ironically on May 30 that he did not see much of a threat from RAF raids, accused the Luftwaffe of failing to defend Cologne and blamed Goering personally for neglecting to provide sufficient flak batteries.

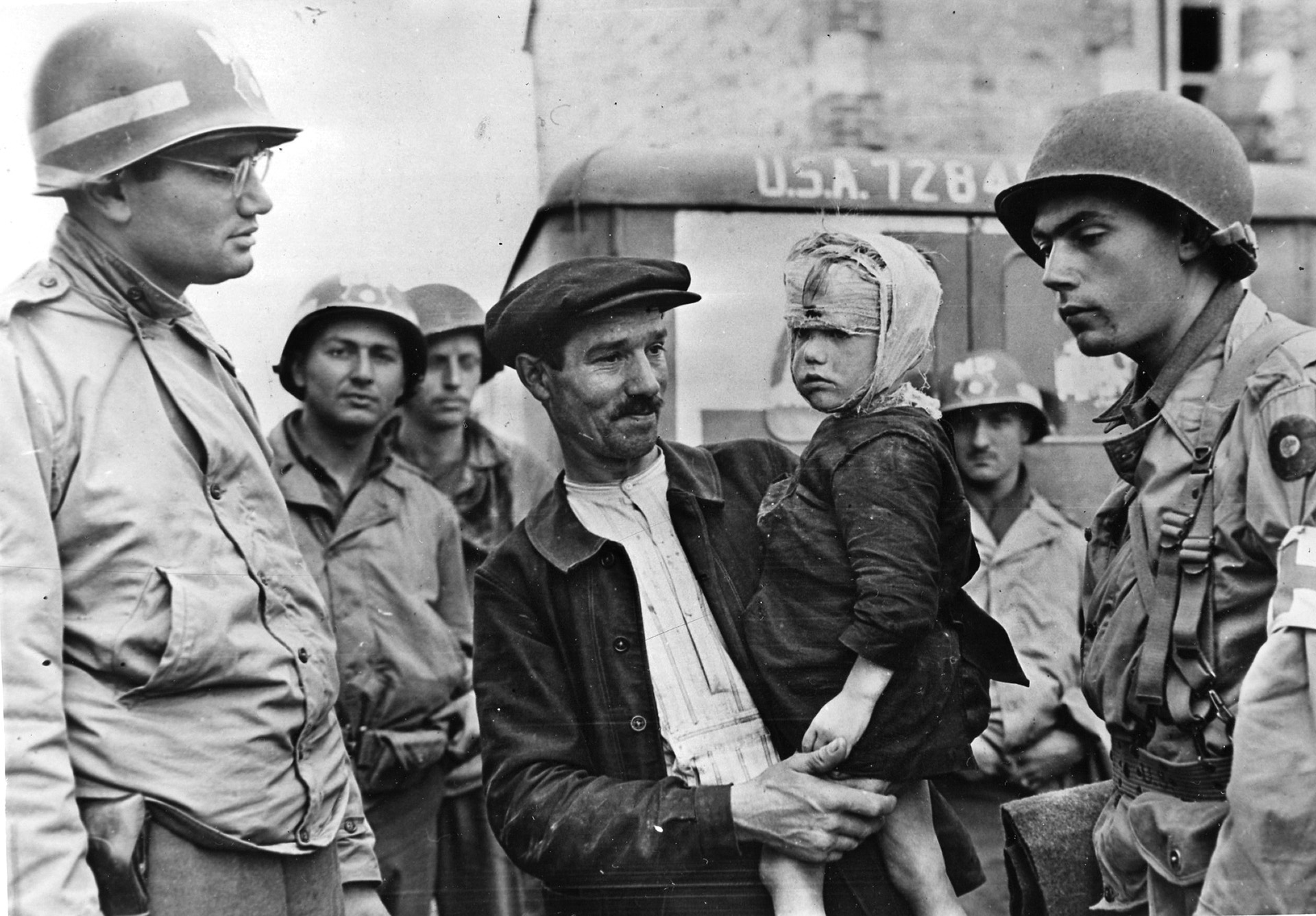

The raid made front-page news from London to New York to Watertown, S.D., and provided a welcome tonic for the morale of the British people, frayed by two and a half years of bombing, hardships, and defeats. Churchill congratulated Air Marshal Harris and Bomber Command on their “remarkable feat of organization,” and telegraphed President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “I hope you were pleased with our mass attack on Cologne. There is plenty more to come.” General Arnold called it “a wonderful show,” and the RAF official history recorded later, “Bomber Command had at last won a major victory against a major target.”

In the infamous Warsaw ghetto, captive Jews rejoiced at the news. Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum, the noted historian and diarist, reported, “Cologne was an advance payment on the vengeance that must and shall be taken on Hitler’s Germany for the millions of Jews they have killed…. After the Cologne affair, I walked around in a good mood, feeling that, even if I should perish at their hands, my death is prepaid.”

The Germans were quick to retaliate for the raid. On the night of May 31, three waves of 25 bombers swept over the historic city of Canterbury in Kent and inflicted heavy damage. But casualties were light, and the famous Anglican cathedral suffered only superficial damage.

Air Marshal Harris had displayed great courage and skill in executing Operation Millennium, and his gamble paid off. The raid captured the imagination of the British and American public, elevated his command presence, won the unreserved admiration of Churchill, and ensured a vigorous future for the bomber offensive, soon to be widened by the B-17 and B-24 bombardment groups of General Eaker’s U.S. Eighth Air Force. The calculated risk taken in the dark skies over Cologne paved the way for Nazi-occupied Europe to be bombed “around the clock.”

Fresh from his triumph, Harris declared, “It is imperative, if we hope to win the war, to abandon the disastrous policy of military intervention in the land campaigns of Europe, and to concentrate our air power against the enemy’s weakest spots…. The success of the 1,000 Plan had proved beyond doubt in the minds of all but willful men that we can even today dispose of a weight of air attack which no country on which it can be brought to bear could survive…. It requires only the decision to concentrate it for its proper use.”

Harris had convinced Churchill and his war cabinet of the value of large-scale bomber missions, so he kept his large force intact and without delay audaciously maintained the offensive. Only two nights later, on June 1-2, 1942, he launched 957 bombers against the Ruhr Valley city of Essen and its 800-acre Krupp armaments plant. But it was a notoriously difficult target to find, and low cloud and haze hampered the RAF raiders. Little damage was done to the city, the Krupp works went unscathed, and 32 planes were lost. Essen was attacked four more times that month.

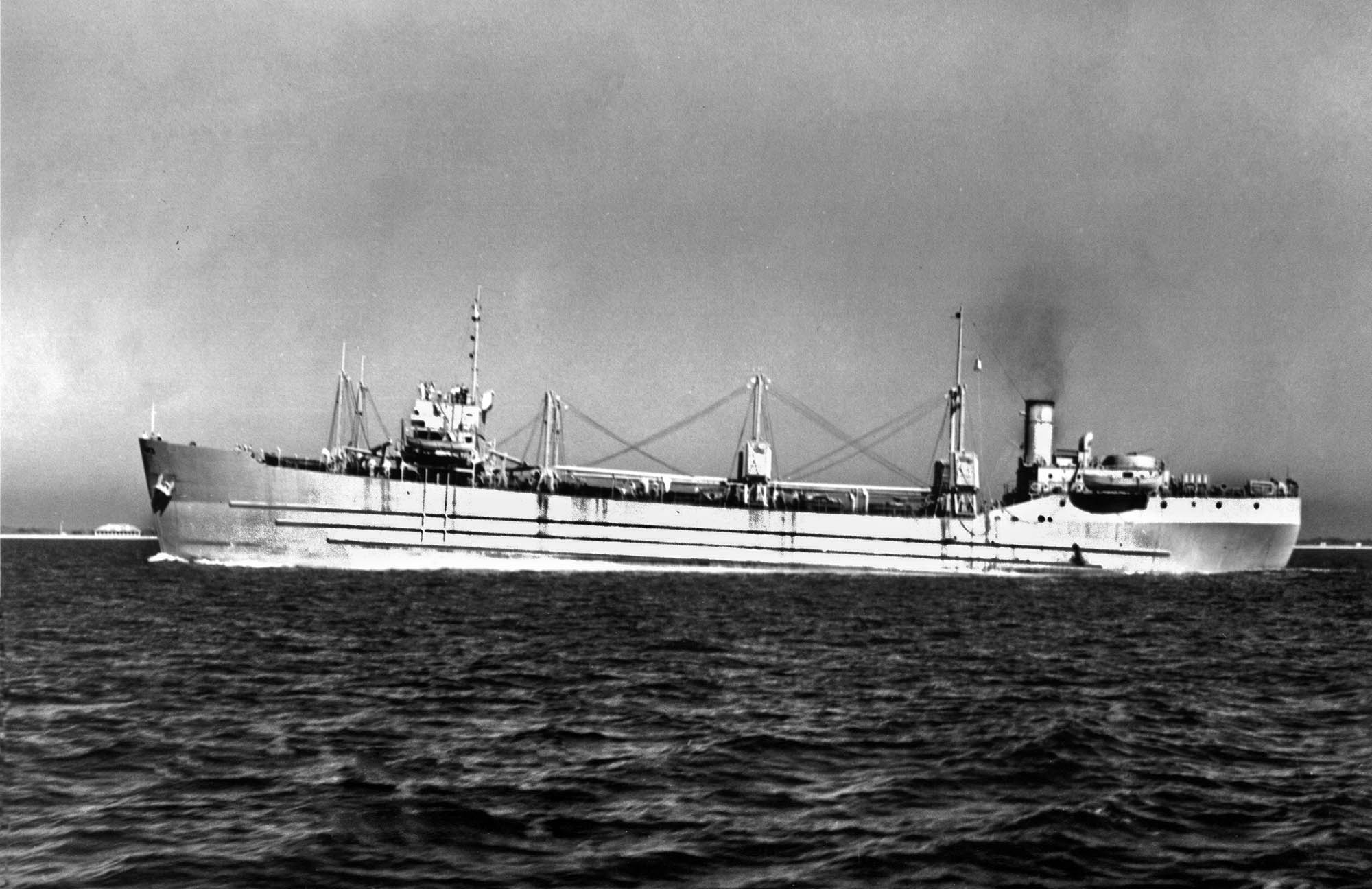

Bomber Command’s next target was the great port of Bremen, with its important docks, U-boat construction yards, and Focke-Wulf aircraft plant. Although the 1,000-bomber force was disbanded, Harris borrowed 20 Wellingtons and 82 twin-engine Lockheed Hudsons from RAF Coastal Command and marshaled 1,003 planes for the June 25-26 operation.

But heavy cloud cover again prevailed, and the results were disappointing. Although Focke-Wulf buildings were hit, the overall damage inflicted was relatively slight and the effect on German production minimal. The raid’s cost to the RAF was high, with 291 crewmen killed. Bomber Command lost 44 planes, four more crashed in the sea, and five Coastal Command aircraft failed to return. Another 65 planes were damaged. The Bremen operation was the last 1,000-plane mission launched until 1944.

Although Air Marshal Harris was able to increase his command’s strength to 50 operational squadrons and still mount some large-scale attacks, the tempo of the air offensive against Nazi-occupied Europe was markedly reduced in the second half of 1942. Missions against the Rhine River port of Dusseldorf on July 31-Aug. 1 and Sept. 10-11 involved 630 and 476 bombers, respectively. They inflicted heavy damage but failed to retard industrial production. Losses remained relatively high.

The air war against Germany escalated dramatically in 1943 as the RAF continued to mount punishing, and often costly, night raids. The great commercial city of Hamburg was reduced to a charnel house with 50,000 dead in late July and early August. That year, Bomber Command flew 64,528 sorties and dropped 200,000 tons of bombs on enemy targets.

Meanwhile, the powerful American Eighth Air Force came into its own, stoutly clinging to the daylight precision-bombing concept and complementing the British nighttime efforts. American losses were high until the advent of long-range P-51 Mustang escort fighters. But, from 1943 until the end of the European war, all German cities and industrial centers felt the weight of Allied bombs. In the final eight months of the war, the USAAF dropped 350,000 tons of bombs on Germany, and the RAF 400,000 tons, 10 times the weight dropped on Britain during the entire war, including V-1 and V-2 rockets.

The air offensive climaxed on February 13-14, 1945, when British and American bombers targeted Dresden, an important rail and communications center for German forces on the Eastern Front. During the night, two waves of RAF Lancasters, totaling 805 aircraft, dropped 2,659 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, setting up the worst firestorm of the war. At noon on February 14, Eighth Air Force B-17s fed the flames with 771 tons of bombs, and on the following day another 210 Flying Fortresses unloaded 461 tons.

The fires raged for four days and could be seen 200 miles away. The raid leveled 1,600 acres in the center of the historic Saxony capital famed for its baroque churches, art galleries, museums, and spacious parks, and the death toll was estimated at between 25,000 and 35,000. Dresden was heavily bombed again on March 12 and April 17 and was captured by Soviet troops on May 8.

The aerial sacking of the ancient city and the killing of so many civilians triggered an uproar from religious and pacifist leaders in Britain, despite the havoc that had been wrought by the Luftwaffe from 1940 onward. When moral questions were raised in Parliament, Prime Minister Churchill called for a review of “the question of the bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing terror, though under other pretext.”

He told Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal, chief of the air staff, on March 28, “The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforth be more strictly studied in our own interests rather than that of the enemy.” An indomitable warrior, but also a humanitarian sensitive to the suffering of civilians, Churchill nevertheless told a Bomber Command officer after the war, “We should never allow ourselves to apologize for what we did to Germany.”

The Dresden raid led Churchill to distance himself from Air Marshal Harris, who became a reviled figure for carrying out—with vigor—the policy of his government. He led a futile campaign to secure a campaign medal for the men of Bomber Command, which had lost 72,350 air-crew personnel in six years of combat. Inexplicably, such recognition did not come for several decades.

Denied a peerage, unlike most other British wartime leaders, Harris resigned in 1946 and was promoted to marshal of the RAF. After retiring to South Africa, he was offered a peerage by Churchill in 1951. He refused, but accepted a baronetcy in 1953, and died in 1984. The Queen Mother unveiled a statue of Harris in London in June 1992, while a Lancaster flew overhead.

The late Michael D. Hull was a frequent contributor to WWII History and resided in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments