By Arnold Blumberg

In the summer of 1864, after six weeks of virtually constant combat in the Wilderness area of northern Virginia, the Union and Confederate armies of Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee settled into an uneasy siege around the city of Petersburg, 23 miles southeast of Richmond. With a population of 18,000, Petersburg was the second largest city in Virginia and the seventh largest in the entire Confederacy. Lead works used for manufacturing bullets, as well as numerous warehouses located within its confines, gave the city a manufacturing value central to the Southern war effort.

The five rail lines radiating out from the town gave it added strategic significance. The Richmond and Petersburg Railroad connected Petersburg with the capital. The Petersburg Railroad, commonly called the Weldon Railroad, ran between Petersburg and Weldon, North Carolina. Together, these two lines provided the only direct rail link between Richmond and the rich resources of the coastal regions of the Carolinas and Georgia. In addition, the South Side Railroad connected Petersburg with East Tennessee, and the Deep South via the Richmond and Danville Railroad. The City Point branch of the South Side line gave the Confederates access to the deep-river port at City Point. Finally, the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad ran through the fertile Blackwater River country before reaching enemy-held Suffolk. Petersburg thus linked Richmond with the rest of the Confederacy, and control of the critical rail hub was vital if Richmond was to be held successfully.

An Opportunity to Take Petersburg

The first direct Union threat to Petersburg was mounted in May 1864, when Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler advanced south of the James River from Bermuda Hundred. Butler’s Army of the James, operating where the Appomattox River entered the James, could have occupied the town in early May, but bad luck and poor leadership prevented its capture at the time. A concerted attempt to take Petersburg occurred on June 15 when the Federals assaulted the town’s outer defenses. The effort lasted for three days and proved another costly Union failure. The missed opportunities of May and June convinced Grant that more frontal attacks on the entrenched positions defending Petersburg would not succeed. He embarked instead on a series of flanking movements to his left and south designed to take the enemy bastion from the rear.

June 22 saw the first Union slide around the Confederate right at Petersburg. That day the Union II Corps was surprised and routed by Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s gray-clad infantry. The next day a Federal try at breaking the Weldon Railroad due south of the city was shattered, again by Mahone and his men. The opposing armies, exhausted and bloodied, began to dig in, and the siege of Petersburg commenced in earnest. It was not a siege in the classical sense; the Confederates were never completely surrounded. From its fortified lines to the east and south of the enemy stronghold, the Union Army would launch repeated expeditions toward the sparsely defended regions to the southwest in an effort to cut the Weldon and South Side Railroads—Richmond’s last links to the outside world. In response, Lee would counter the enemy thrusts with blocking movements and counterattacks of his own.

During July, active operations shifted north of the James River as the Federals attempted to take Richmond by delivering an assault from the Union bridgehead at Deep Bottom on the north shore of the James River. Although another failure, the effort did have one promising result. To counter the enemy thrust at Richmond from Deep Bottom, Lee withdrew four infantry divisions from south of the James, leaving only four weak infantry divisions to guard the vital Weldon and South Side Railroads. Realizing that the Petersburg front had been weakened, at least temporarily, the relentless Grant looked for a way to exploit the new situation.

The Dimmock Line

The defenses Grant sought to breach stretched along high ground for 10 miles around Petersburg, beginning and ending on the Appomattox River and protecting all but the northern approaches to the city. Fifty-five partially enclosed artillery batteries, consecutively numbered from east to west, were linked together by trenches. The cannons and crews manning the line were protected by earth and log forts, while large pits were dug for the placement of mortars. Communication trenches leading to the rear allowed for relatively safe passage to and from the front, while earthen bomb-proofs afforded shelter for troops stationed behind the main line of resistance. Officially called the “Dimmock Line” after Confederate engineer Captain Charles Dimmock, who had supervised the construction of the Richmond defenses, the works around Petersburg had been built up and improved upon over the past two years.

As formidable as the Dimmock Line appeared to be, it had some serious weaknesses. Between Batteries 7 and 8 a deep ravine provided a route of penetration for an attacker. Near the Jerusalem Plank Road, between Batteries 24 and 25, south of the city, a second ravine along Taylor’s Creek created a gap in the Confederate site that made for a potential breakthrough point. Furthermore, many of the artillery pieces ringing the town were placed above the parapets, exposing them to enemy fire, while their own fields of fire were obstructed by wooded areas to the front. The log and earthen forts housing the cannons could be attacked easily from the rear since none was fully enclosed. Lastly, the entire complex never had enough men to properly garrison it. This was underscored when the outnumbered Confederates had to give up the line’s outer works and retreat to the inner defenses following the enemy attacks on June 19-20.

Facing the Confederate fortifications surrounding Petersburg, the Army of the Potomac built its own strong, static siege lines. Thirty-one forts, some as large as five acres, were created. The forts could hold 10 to 30 guns and 300 men, while additional field works could accommodate four to six pieces of artillery and as many as 200 troops. Most of these sites were fully enclosed and strengthened by gabions, abatis, and chevaux-de-frise and built close enough to each other to provide mutual fire support. Bomb-proofs were laid out every 20 yards. High parapets for infantry to hide behind, with obstacles such as ditches to their front, connected the entire line. For good measure, a reverse line facing to the rear was created a short distance from the front works. The architect of the Union field engineering effort at Petersburg was Major James C. Duane, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac.

The Federal Trenches Around Petersburg

After the failed assault on the town during the second half of June, the Army of the Potomac was arranged around Petersburg with XVIII Corps (part of Butler’s Army of the James) resting on the Appomattox River and stretching south to link with the right wing of IX Corps, followed by V Corps, which connected with IX Corps’ left. II Corps was held in the immediate rear as a ready reserve. IX Corps was closest to the enemy works, about 100 yards to the west, and occupied sloping ground that fell off to a ravine in the rear. Through the ravine passed Taylor’s Creek and part of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad.

Life in the trenches was both hard and dangerous. Troops would usually spend a 24-hour shift on the picket line, where they observed the enemy and engaged in frequent skirmishes. Within short rifle range of the opposing lines, soldiers had to keep low, and could only be relieved during the hours of darkness. Deadly Confederate marksmen, armed with English-made Whitworth rifles, were especially adept at picking off unwary targets. One sniper dropped two Union soldiers at a well, several thousand yards away, with a single shot—they were dead before the shot was heard. Enemy trench raids, usually conducted just prior to dawn, added to the tension. As if the threat of sniper fire was not enough, life in the trenches at Petersburg also brought with it lice, swarms of flies, summer heat, lack of water, and cramped quarters. The stench of decaying bodies that could not be removed to the rear due to enemy fire was, as one New York infantryman remarked, “constantly in our nostrils and settled in our clothes.”

From late June on, IX Corps found itself under the guns of the Rebel fortifications protecting Petersburg. The corps was the smallest in the Army of the Potomac, with a complement of only 39 regiments, about half of the number in other corps (II Corps, for example, had 83 regiments). Along with II Corps, IX Corps had suffered the majority of the 10,000 losses sustained by the army in the assaults on Petersburg between June 15 and 18. During the battles of May and June, five brigade leaders had been lost to wounds, and many experienced staff officers had been killed or disabled. By early July it was common to see regiments led by captains, while many colonels now commanded brigades.

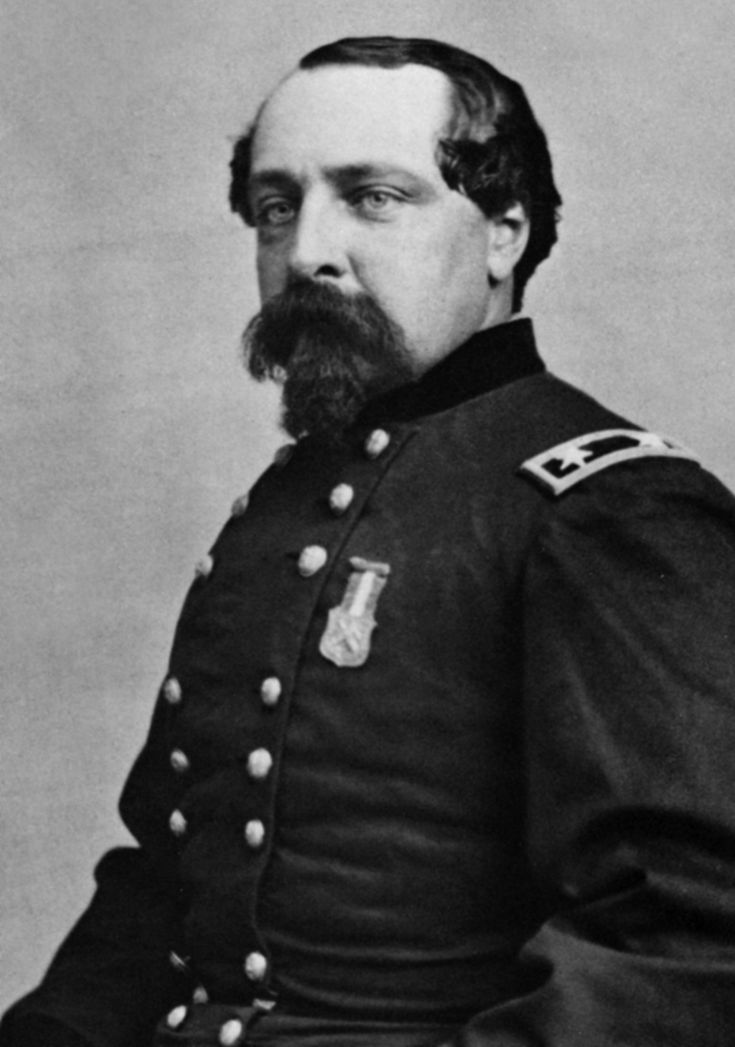

Ambrose Burnside: A General out of Retirement

If IX Corps was bled white and exhausted as it settled in for the siege of Petersburg, the same could be said of its commander, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside was 40 years old in 1864, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Class of 1847. After serving in the Mexican War and on the southwestern frontier, Burnside retired from the Army in 1853 to engage in the gun-manufacturing business. He later took a management position with the Illinois Central Railroad. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he raised the 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment, led an infantry brigade at First Manassas, and was soon promoted to brigadier general of volunteers. For a string of minor successes on the coast of North Carolina in 1862, Burnside was promoted to major general.

Following the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, where his performance as head of IX Corps was mediocre, Burnside was placed in command of the Army of the Potomac that November. The next month he led the army to a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Replaced as army commander, Burnside was transferred to the Department of the Ohio in March 1863. His successful defense of Knoxville, Tennessee, during the winter of that year paved the way for his reassignment back to the eastern theater and command of his old IX Corps the next spring.

Burnside’s second tenure with the Army of the Potomac was a difficult one. Both officers and enlisted men resented him for his bloody failure at Fredericksburg the year before and viewed him (rightly) as a critic of deposed Maj. Gen. George McClellan, a man whom many in the Army of the Potomac still revered. By the conclusion of the Overland Campaign, Grant’s confidence in Burnside and his IX Corps was all but exhausted. The Union commander felt that Burnside and his men were slow to execute orders, sluggish on the march, and unreliable in combat. And then there was the issue of the black troops in Burnside’s command.

Controversy With the 4th Division

At the start of the Virginia campaign of 1864, there were 18 infantry and two cavalry regiments, as well one artillery battery, of United States Colored Troops (USCT). Commanded by white officers at the company, regimental, and brigade level, none of the African American soldiers had performed any duty other than mundane camp work, engineering and fatigue details. Northern racism fueled the supposition that the former slaves could never be trained to fight effectively. The creation of two all-black infantry divisions, one in IX Corps, was looked upon by the military as a politically motivated experiment. The Army was never sure what role the black troops should play in the war, and thus watched their activities with a critical and judgmental eye.

The African American infantry in the Army of the Potomac, nine regiments grouped into the 4th Division, had not been given a chance to prove itself during the Overland Campaign. The full-strength formation did little more than guard the vast wagon trains supporting Grant’s move from the Rappahannock River to south of the James. By mid-July, with the army stalemated at Petersburg, the men of the division spent their days providing fatigue parties for other corps facing the Confederates. No time was allowed for them to train or engage the enemy. The army’s titular commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade (Grant commanded all the armies in the East), felt that he could not rely on the colored troops to guard the trenches or skirmish with the enemy. He preferred to keep them employed in work details.

The leader of the 4th Division, Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero, spent much of July attempting to get his rapidly tiring troops off these work details. His reasons for doing so were twofold: first, division morale and cohesion were breaking down due to the fragmentation of his unit resulting from constant detachment as laborers; second, he had been informed by Burnside early in the month that his men might have to lead the assault on Petersburg’s works after the successful completion of a top-secret mining operation that was then being conducted in IX Corps’ sector. Unfortunately, Ferrero’s pleas to his superiors for time to gather his division and prepare it for the coming action were ignored. Little respect for his black troops, and even less for him, made Ferrero’s requests fall on deaf ears.

The 33-year-old Ferrero had been a successful dancing instructor in New York City and a lieutenant colonel of militia. He participated in Burnside’s North Carolina expedition in 1862 as colonel of the 51st New York Infantry. At that rank, he led a brigade in the IX Corps at Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. His performance was lackluster. His leadership of a division at the siege of Knoxville was passable at best and did nothing to engender respect from his superior officers when he came East. To top it off, there was bad blood between Ferrero and his corps commander. After the debacle of Fredericksburg and the embarrassment of the Mud March that followed, Burnside demanded that a number of officers he deemed insubordinate be removed from their posts. One of them was Ferrero.

A Plan to Mine the Confederate Lines

The plan to explode a mine under the Confederate lines, thus opening a breach in the town’s defenses, was first proposed by Brig. Gen. Robert G. Potter, leader of the 2nd Division, IX Army Corps. Since late June his command had held the Union trench works west of Taylor’s Creek. From this vantage point he observed a bulge in the enemy line, 100 yards to his front. Dubbed Elliott’s Salient after Confederate Brig. Gen. Stephen Elliott, Jr., whose South Carolina troops occupied it, the salient contained a small redoubt guarded by a four-gun artillery battery. The brigadier surmised that an underground mine set off beneath the fortification could create a gap in the enemy lines that might lead to the capture of Petersburg itself. Potter sent his proposal to his corps commander, Burnside.

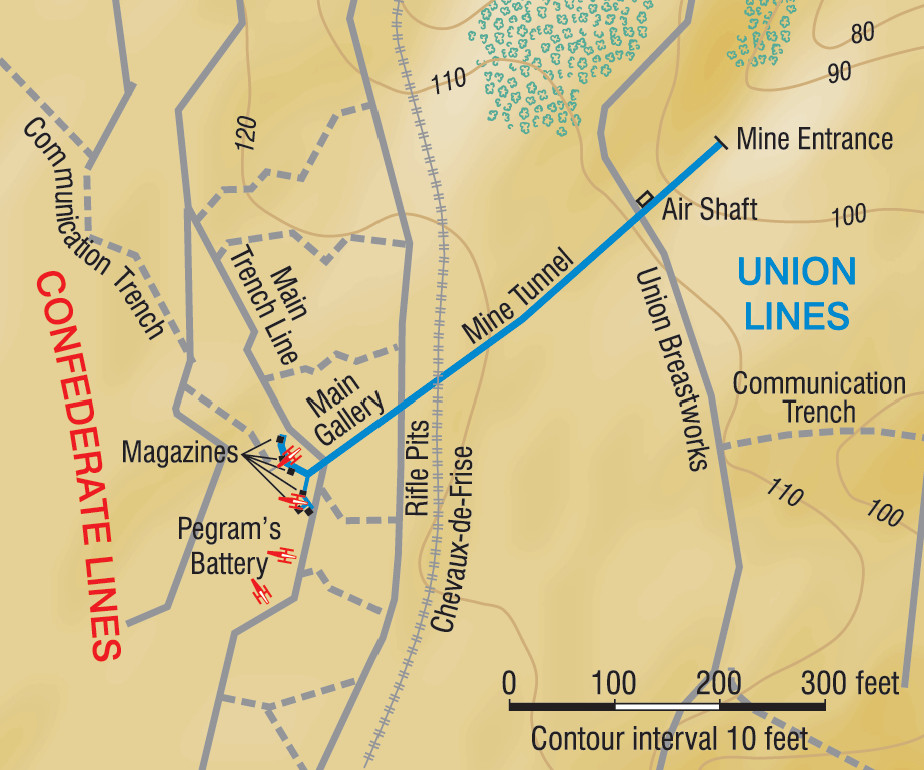

Unknown to Potter, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment had come to the same conclusion about the feasibility of mining under the Confederate position. A trained railroad engineer who had participated in drilling a 4,200-foot tunnel through the Alleghenies in the 1850s, Pleasants had both the personal experience and the skilled coal miners in his own regiment to do the job. He and Potter went to discuss the project with Burnside on June 25. Despite the corps commander’s initial doubts, Pleasants obtained permission to begin the tunnel the next day.

Within 72 hours of opening the mine, Pleasants and his men had burrowed 130 feet—a quarter of the distance to the enemy fort. While Pleasants’ men toiled, Meade and Duane looked on with skepticism. Both felt certain that the project would fail and did their part to make that prediction come true by withholding all material aid. Pleasants had to scour the rear areas of the army to find the necessary wood and tools required for the job. By mid-July, the tunnel was almost completed. Pleasants requested from the artillery chief eight tons of black powder and 1,000 yards of safety fuse. What he got was only four tons of powder and a blasting fuse—not the requested safety fuse. Nevertheless, on July 28, Pleasants reported that the mine was ready to be activated. Some 320 kegs of gunpowder, weighing a total of 8,000 pounds, had been placed at intervals inside the 510-foot tunnel, primed for explosion with a 98-foot-long fuse.

Cemetery Hill: Key Objective at Petersburg

While Pleasants’ men dug, Burnside finalized a plan for the follow-up assault. As he envisioned it, the attack would take place before dawn with the lead units in column formation and engineers at the head of each formation to clear away any obstacles in their path. Grant, in turn, ordered a diversionary move by Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock’s II Corps and a few thousand cavalry north of the James River in the hopes of drawing off enemy forces from Burnside’s front. Grant also ordered Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps and Maj. Gen. Edward Ord’s XVIII Corps to ready themselves to support IX Corps’ effort.

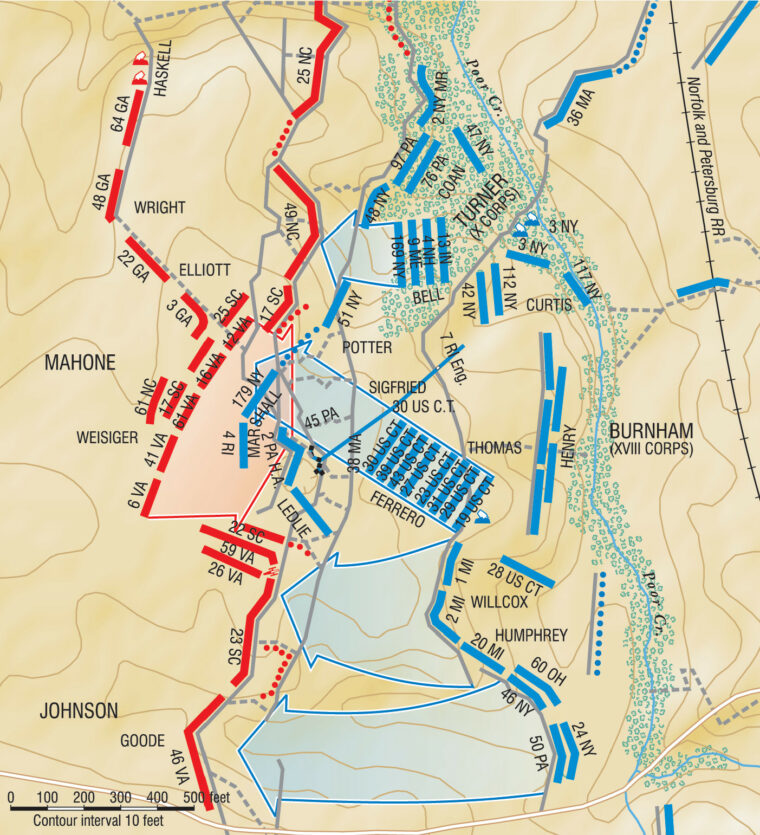

The key to Burnside’s plan was getting to the high ground 400 yards northeast and behind the Confederate lines near the town of Blandford, just east of Petersburg. Running parallel to the enemy works was the Jerusalem Plank Road, heading north. Topping the summit was a small brick church and cemetery that gave the hill its mordant name—Cemetery Hill—in subsequent reports. Burnside envisioned his black troops conducting a lighting thrust through the hole created by the mine, supported on the left flank by the 3rd Division and on the right flank by the 1st Division, with the 2nd Division following closely behind.

Ferrero’s division was chosen to lead the attack. Burnside picked the troops for a number of reasons. First, although lacking combat experience, they were relatively fresh and up to strength with 4,300 men, something that could not be said of IX Corps’ three white divisions, which were low in numbers as well as morale. Second, unlike the battle-wise troops of the white units, who Burnside felt would go to ground as soon as they advanced beyond friendly entrenchments, the black soldiers would be eager to prove themselves and would attack without hesitation. Ferrero was ordered to detach a regiment from each of his two brigades to clear the enemy trenches to the left and right of the breach made by the exploding mine.

On July 26, Burnside presented his plan to Meade, who in no uncertain terms forbade the colored troops from leading the assault. Furthermore, Meade ordered the attack to be a straight drive for Cemetery Hill, with no forces being spared for clearing the adjacent Confederate works. Meade went to Grant and convinced him that to allow black troops to head the attack would bring down a political firestorm from radical abolitionists in the Lincoln administration if the operation failed and the black division incurred great loss of life. Grant agreed and gave his approval for Meade’s revised attack plan.

A New Plan by Burnside

With his carefully thought-out scheme for the advance on the Petersburg fortifications rejected, Burnside had to construct a new one from scratch. He sent for the commanders of his three white divisions—Brig. Gens. James H. Ledlie, Robert B. Potter, and Orlando B. Wilcox—and told them to decide among themselves which one of their formations would now lead the attack. (Ferrero was not at the conference, having been granted leave on July 21 to travel to Washington to lobby Congress in person for his yet unconfirmed brigadier rank. He would not return to the front until the late afternoon of the 29th, barely eight hours before the mine was set to go off.) Several hours of unproductive discussion followed, with no one volunteering for the dangerous assignment. Frustrated by the proceedings, Burnside finally had the generals pick lots. Ledlie drew the dubious honor of leading the attack, which was to commence barely 12 hours hence.

Burnside was likely disappointed with fortune’s choice of Ledlie and his men to spearhead the assault. Burnside had previously expressed his opinion that the unit’s soldiers “are worthless. They didn’t enlist to fight.” His opinion of Ledlie was no better. Ledlie was a 32-year-old civil engineer who had worked on railroads before the start of the war. He was appointed a brigadier general in 1863 after unexceptional service on the Carolina coast and as post commander at various locations in the Department of Virginia and North Carolina. Rising from brigade to division command by June 1864, he had spent the better part of the summer attempting to resign from the army. His notorious lack of personal bravery, barely masked by his addiction to drink, made him an object of scorn by officers and enlisted men alike.

During the evening of July 29, Burnside issued written orders to his divisions, setting down their precise responsibilities for the coming attack. Ledlie’s division was to press through the gap created by the mine and seize Cemetery Hill. Wilcox’s men were to follow on the heels of Ledlie, then turn left to form a protective shoulder, while Potter’s command, following Wilcox, created a blocking position to the right of the penetration. Ferrero’s men would pass through the 1st Division and occupy the Petersburg suburb of Blandford. Burnside hoped the attack still would have the element of surprise on its side—for the last several weeks the frontline troops and the Petersburg newspapers speculated about a Yankee mine being planted, and the Confederates had dug countermines to discover its location—without success.

The mine was scheduled to go off at 3:30 am; its eruption was the signal for the all-out Union attack. The designated time came and went and no explosion occurred. The three spliced-together fuses that were supposed to spark the gunpowder had gone out. Lieutenant Jacob Douty and Sergeant Harry Reese volunteered to enter the mine and relight the fuse. Impatient at the delay, Meade asked Burnside repeatedly what had gone wrong. His last query ordered the corps commander to commence the attack immediately, whether or not the mine went off. Finally, at 4:44 am, the planned explosion occurred.

Five Minutes of Falling Debris

The ensuing blast “would have done credit to several thunderstorms,” a Union soldier remembered. The explosion set off ground tremors that were felt for several hundred yards in all directions. Followed by a muffled rumbling noise, almost in slow motion, the fort, its cannons, and garrison were lifted 100 feet into the air by a mushroom-shaped cloud. Debris did not stop falling to earth for a full five minutes, and observers said “a heavy veil of smoke stood for a moment over the wreck [crater] as if reluctant to reveal the destruction.” As the sound of the explosion died away, it was replaced by the blasts of 164 Union cannons and mortars directed at the Confederate lines.

Awed by the noise and the apparent devastation caused by the mine, the first wave of Federal troops did not leave their trenches for a full five minutes, their eyes and mouths wide open in disbelief. But within 10 minutes, their officers roused them to the attack. They followed the axe-wielding sappers, whose task it was to knock down the man-made obstacles implanted in the no-man’s-land between the Union and Confederate lines. After sprinting about 130 yards, the blue columns of Ledlie’s division poured into the exploded fort, preceded by engineers who began reversing the face of the enemy trenches and digging a covered way from the Crater back to their own works.

Charging into the Crater

Elliott’s Salient was now a chasm 135 feet in length, 97 feet in breadth, and 30 feet in depth, with a rim 12 feet high. The huge blast had annihilated Captain John Pegram’s battery and many of the men in the 19th and 22nd South Carolina Infantry Regiments, about 250 in all. Into the hole swarmed the Union brigades of Colonel Elisha G. Marshall and Brig. Gen. William F. Bartlett. Picking their way through the debris, the men attempted to climb the pit’s outer lip, but found the going difficult because of the loose sand and clay that made up the pit’s sides. Scattered fire from Confederate trenches adjacent to the Crater drove many of the Bluecoats to ground before they could move forward. Meanwhile, Colonel John F. Hartranft’s 1st Brigade went forward into the enemy trenches to the left of the blasted ground while Colonel Simon G. Griffin’s 2nd Brigade did the same on the right. Brig. Gen. Zenas Bliss’s brigade followed in support. Sweeping the enemy positions with musketry and bayonets, the Federals cleared the Confederate emplacements for 100 feet in both directions.

It was now about 5:30 am and small-arms fire from the dirt-encrusted survivors of Elliot’s command, in concert with artillery concentrations from Cemetery Hill, prevented any Union forward movement. Many of the Union troops began spilling back into the Crater to avoid the enemy fire. There they found the huddled masses of Bartlett’s and Marshall’s men, who would not budge. They had lost all unit cohesion and could hardly move within the confines of the smoking hole and the surrounding trenches. The arrival of Bliss’s brigade only made the situation more chaotic. Along the 1,000-foot front confusion reigned—no one seemed to be in charge.

The one officer who should have been on hand to sort out the mess was Ledlie, but he had ensconced himself in a bomb-proof shelter not far from the fighting. Fortifying himself with rum supplied by an army surgeon and complaining constantly of ill health, Ledlie from time to time would send orders to his commanders to take the high ground north of the Crater. He never left the shelter to see for himself if his directives were being carried out.

Meade, furious with the lack of progress by IX Corps, sent Burnside a peremptory order at 6:30 am that the attack must get moving and that Burnside should commit all his strength to the assault. For the next hour, fragments of Griffin’s, Bartlett’s, and Marshall’s brigades attempted vainly to capture Cemetery Hill. Supported by Colonel William Humphrey’s brigade, the attack was repulsed by Confederate flanking fire and stiffening enemy resistance north of the Crater. Meanwhile, just behind the Union trench system, Ferrero’s division had been waiting since 5:30 for the order to join the battle. That order finally came at 7:15. Ferrero received it in the same dugout that Ledlie had been calling home since the battle began three hours before. Ferrero wanted to wait for Ledlie’s command to make his own advance, but further instructions from Burnside forced him to move sooner than he wanted. Gulping down a fortifying cup of rum, Ferrero left the bunker to get his men moving.

At 7:30 Ferrero’s 1st Brigade, with Colonel Joshua K. Sigfried leading the way, plunged into the Crater, closely followed by Colonel Henry G. Thomas and the 2nd Brigade. Somehow, Sigfried and his men were able emerge from the gaping hole into the maze of trenches and traverses behind it. Thomas’s regiments moved to the right of the Crater and found themselves in a warren of trenches, crowded between units from other divisions. While attempting to sort out his regiments, the colonel received a message from Ferrero to attack Cemetery Hill. Forming in the open as best they could, the Union troops made a valiant charge, but collapsed in the face of a Confederate counterattack. The beaten men ran for safety back into the Crater and the trenches adjoining it. It was 8:30 am and the last Union offensive of the Battle of the Crater already was over.

“Little Billy” Mahone

Not long after the mine went off, Lee was notified of the situation by General P.G.T. Beauregard. Bypassing the usual army chain of command, Lee immediately contacted Mahone, whose 3,000-man division was located two miles south of the raging battle near Lieutenant Creek. Lee needed a man of action capable of dealing with the current crisis—he knew Mahone fit the bill. A graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and a railroad engineer before the war, Mahone’s first command was the 6th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment. During the Peninsula Campaign he had led an all-Virginia brigade of infantry. After his sterling performance in the Wilderness battles, he was given Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division when Anderson took over I Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia after Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s wounding on May 6. “Little Billy,” as the 100-pound, short and wiry Mahone was dubbed by his comrades, had sharpened his command into seasoned shock troops by the fourth summer of the war

Mahone had heard the mine explosion but was not aware what it meant until Lee’s order reached him at his headquarters near the Wilcox Farm. Told to send two of his five brigades to the scene, Mahone decided to lead them himself. He quickly got Colonel David Weisiger’s Old Dominion Brigade and Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright’s Georgia Brigade (temporarily commanded by Colonel Matthew R. Hall) into marching order. These units started on their journey around 6 am, taking a roundabout route through ravines to conceal them from Federal observation.

Racing ahead of his moving formations, Mahone found Beauregard, who gave the Virginian the authority to conduct the operations against the Union threat at the Crater as he saw fit. Leaving Beauregard, Mahone made his way down the Jerusalem Plank Road, passed Cemetery Hill, and traversed a covered way a few hundred yards from the Confederate front. Following the covered way, the general entered a shallow ravine that ran parallel to the main trench line. Mahone climbed a slight rise and observed firsthand the chaotic situation at the Crater. He determined that he would need as much of his division as possible to deal with the mob of Union forces in and around the smoldering breach. He called for Colonel John C. Sanders’s Alabama Brigade to join him immediately.

“No Quarter, No Quarter!”

As Mahone scouted the Federal position, Weisiger’s and Wright’s men cautiously approached, their progress hampered by heavy artillery fire. The 800 Virginians passed the cemetery and entered a ravine that lay directly opposite the Crater. They were ordered to lie down, fix bayonets, and prepare to attack. Seeing Thomas’s black regiments preparing to come forward, the Confederates moved against them. The Virginians, followed by several North Carolina regiments, struck the Federals’ front and flank just north of the Crater. Suffering heavy losses, the black troops were thrown back amid angry Confederate cries of “No quarter, no quarter!” Several black soldiers captured during the melee were killed on the spot by their captors.

The retreating Federals were driven back to the Crater and the surviving trenches on either side. The Union troops were packed together so tightly, said one Federal officer, that “it was impossible for any to use their muskets, and when the enemy, in overwhelming numbers charged down upon us, they found us in this defenseless condition. Surrender or death were the only alternatives present.” Another Union officer remembered how his men found it almost impossible to move their arms or legs—let alone fire their weapons.

Fear spread quickly among the troops inside the Crater. As soon as Confederate rifle barrels were seen pointing over the Crater’s rim and discharging into the milling masses, fear turned to abject panic. Some men tried to shoot their guns, others tumbled out of the hole and ran headlong for the Union lines. The white soldiers attempted to keep the black troops in front of them as human shields.

“Close Quarters with the Bayonet and Rifle Butt Freely Used”

The fight continued in full flood, and the Confederate defenders paid in blood as well. Captain John E. Laughton, with the Virginia Brigade, recalled that his unit of over 100 men was almost wiped out. Another Confederate officer described the combat as taking place at “close quarters with the bayonet and rifle butt freely used.” Despite the fury of their attack, Weisiger’s men could not clear the Crater of the dense throngs of enemy troops inside it. They had lost half their strength because of fire coming from the Crater and the nearby trenches. Mahone sent Wright’s brigade to the south of the Crater to take some of the pressure off the Virginians. The Georgians swung to the rear of the Federals, only to meet determined resistance from Hartranft’s and Humphrey’s commands, which occupied part of the fort not demolished by the explosion. The Bluecoats were supported by two captured artillery pieces. A Confederate officer remarked that as “soon as the Georgians got near enough the enemy opened fire, and they [the Confederates] fell like autumn leaves.” Wright’s men had to retreat.

Confederate small-arms fire was joined by increasing numbers of cannon and mortar rounds. The exhausted Union forces inside the Crater realized that no help would be forthcoming—the Union high command had not even considered it. Their only salvation lay in retreating over the shell-swept ground. A message from Burnside to the brigade leaders in the Crater sanctioned a withdrawal. Word passed down the line to the respective units to prepare to make a dash for safety. An officer was sent back to the Federal trench line to arrange covering fire by friendly artillery. Just as the movement to the rear was about to commence, the Confederates launched another counterattack. Mahone hoped to pin down the enemy left while he administered the coup de grace. Mahone told Sanders and his men to advance to the Crater without firing and make for that part of the fort that had not been shattered by the mine blast. Once under its cover they were to shoot into the Crater and capture or drive out its defenders.

The final Confederate attack started at 2 pm, preceded by the opposing artillery pounding each other. Arms shouldered, the Alabamans moved out immediately, raised a yell, and made a beeline for the fort’s walls. Union musket fire proved ineffectual because of the speed and surprise of the southern attack. The Confederates approached within 100 feet of their target before they were even seen. With little enemy rifle fire directed at them, Sanders’s brigade reached the crest of the Crater and poured volley after volley into the stunned Union troops. Not only bullets but chunks of wood, clods of dirt, spent cannon balls, and discarded bayonet-tipped muskets were hurled at the huddled and demoralized enemy. Then the Confederates surged in to the Crater itself using clubbed muskets and bayonets with great execution. In a matter of minutes the Federal defense fell apart; some soldiers surrendered, others attempted to flee back to the main Union lines through an intense gauntlet of fire. Many of the black troops were cut down by Sanders’s men as they tried to surrender.

The End of Burnside’s Military Career

The Battle of the Crater cost the Union army 504 men killed, 1,881 wounded, and 1,413 captured—a total of 3,475. Of this total, Ferrero’s African American division suffered 1,327 losses, including 209 killed. Confederate losses were about half those of their Union opponents. The greatest loss, 677 men, came from Elliot’s command, which had been standing on the ground above the mine.

The battle ended Burnside’s military career; Ledlie resigned his commission in early 1865. Ferrero, although roundly criticized for his poor performance, somehow retained his division command and later was promoted to brevet major general. Mahone, for his part, was made a major general immediately after the battle. The Crater was a painful Union disaster, a great opportunity carelessly executed and quickly forfeited. The final judgment belonged to Grant, who called the battle “a stupendous failure … the saddest affair I have seen in this war.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments