By Lawrence Weber

On Saturday, September 26, 1863, six days after the Battle of Chickamauga, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet wrote Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon, saying, “I am convinced that nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander.” Referring to Braxton Bragg, the commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, Longstreet went on to say, “When I came here I hoped to find our commander willing and anxious to do all things that would aid us in our great cause, and ready to receive what aid he could get from his subordinates. It seems that I was greatly mistaken.”

Longstreet’s letter is filled with desperation and anxiety, and the Confederates were victorious in the battle. In poetic language, Longstreet summarized the situation in the Western Theater as he currently saw it: “Our most precious blood is now flowing in streams from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains, and may yet be exhausted before we have succeeded. Then goes honor, treasure, and independence.”

Early summer 1863 had been a disaster for the Confederacy with devastating losses at Gettysburg in the East and the fall of Vicksburg in the West. Largely overshadowed by those monumental Union victories, but in many ways no less important, was Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s brilliant tactical and strategic victory over Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee in the Tullahoma Campaign, essentially securing middle Tennessee for the Union and positioning the Army of the Cumberland for a direct strike on Chattanooga, Tennessee, the gateway to Georgia and the Deep South. With the Father of Waters running unvexed to the sea for the Union in the West and the Army of Northern Virginia’s aura of invincibility shattered in the East, it was up to Bragg at Chattanooga to defend the Deep South from a Union invasion and salvage the dimming ray of hope for the Confederate cause.

In late summer of 1863, the Union Army of the Ohio, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, was threatening the Army of Tennessee’s Third Corps, commanded by Confederate Maj. Gen. Simon Buckner, at Knoxville, Tennessee, to the north. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland was targeting Bragg’s position at Chattanooga to the south, and Bragg knew that he would be called upon to reinforce Buckner’s position at Knoxville, which was in imminent danger from Burnside’s forces.

If Bragg was going to successfully defend the critically important transportation and supply city of Chattanooga from an impending attack by Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, he simply could not justify ordering reinforcements to Buckner at Knoxville.

Bragg was determined to maintain possession of Chattanooga at all cost. If one of the last pivotal cities in Tennessee had to fall to the Union, it would have to be Knoxville. Bragg reasoned that the distance between the two cities was so great that spreading their military line so thin would be dangerous, especially since he had also received intelligence that Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland was on the move again, this time attempting to outflank his position from the south by way of the city of Bridgeport, Alabama. With Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Ohio threatening to cut Buckner’s Third Corps off from Bragg at Knoxville via the northeast and Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland attempting to outflank Bragg’s Army of Tennessee from the southwest, Bragg ordered Buckner to abandon Knoxville in early September 1863, with “great regret and reluctance,” and move closer to his position at Chattanooga along the Hiwassee River.

Everywhere he went, disappointment and failure seemed to haunt the mercurial Braxton Bragg, especially when he looked back upon events in the Kentucky and Murfreesboro Campaigns. Humiliated by the lack of confidence his lieutenants had demonstrated in his ability to successfully command (several corps commanders, including Lt. Gen. William Hardee and Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk attempted to secure Bragg’s removal from command of the Army of Tennessee by unsuccessfully petitioning Jefferson Davis in Richmond), Bragg decided to ask his generals for a vote of confidence. Like Bragg’s recent military setbacks, the vote of confidence backfired when the majority of generals openly rejected him. On the eve of the Chickamauga Campaign, Bragg had all but lost the morale of his army.

Before Bragg could stop Rosecrans’s flanking maneuver from engulfing his position, soldiers from the Union’s XIV and XX Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas and Maj. Gen. Alexander McDowell McCook, respectively, were moving into Georgia through several mountain gaps southwest of Bragg’s position. To Bragg, it was clear that Rosecrans’s army was not only targeting Chattanooga, but perhaps clearing a path for a deeper invasion of the lower southeast through Georgia to the Atlantic. On September 9, 1863, in a letter to Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon, Bragg wrote, “Rosecrans’ main force had obtained my left and rear. I followed and endeavored to bring him to action and secure my connections. This may compel the loss of Chattanooga, but is unavoidable.” With Lookout Mountain still between the Army of Tennessee and the Army of the Cumberland, Bragg reluctantly withdrew from Chattanooga to meet the enemy at the mountain gaps. Bragg moved his army to La Fayette, Georgia, and positioned his men directly across the center of the XIV Corps line, which “checked the enemy’s advance, and as I expected, he took possession of Chattanooga.”

As difficult as it was to surrender Chattanooga to the enemy without a fight, Bragg knew that Rosecrans was making a critical mistake in dividing the Army of the Cumberland across three distant locations: Chattanooga, Davis’ Crossroads, and Alpine. If Bragg could attack each Union corps separately, he could destroy the Army of the Cumberland, reclaim Chattanooga, and save the Deep South from an enemy invasion. It was an audacious plan, and time would be of the essence if it was to be carried out successfully.

Bragg authorized a strike at the center of the Union position just west of the Dug Gap along Pigeon Mountain on the morning of September 10, hoping to draw the XIV Corps into a trap without adequate access to timely reinforcements. Dispatching several Confederate divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. Thomas Hindman from Longstreet’s corps and Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne from Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill’s corps, into the wooded gap in the mountain, Bragg’s forces were instructed to draw the enemy into battle and then crush them with their superior numbers.

The lead division of the Union XIV Corps, the Second Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. James S. Negley, was completely unaware that his men were marching straight into the heart of Bragg’s main army. When skirmishing erupted in front of Dug Gap, the surprised Union soldiers courageously drove the Confederates back into Dug Gap. But on gaining higher ground, the Union troops noticed that Bragg’s men had them nearly surrounded with superior numbers. At that moment not a single unit of Federal troops was in supporting distance of Negley, whose troops were isolated near the western end of Dug Gap, and therefore easy prey for the enemy. With Hindman’s men on the Federal left, Cleburne’s forces directly in front of him and on his right, and Buckner’s corps supporting them in reserve, Negley was in a perilous situation. As the sun was setting on this dangerous encounter, Negley withdrew his men into the woods west of Dug Gap and alerted Thomas of his situation.

On the Confederate side, speed was the key to the strike, and everyone seemed to understand that except Hindman. On the eve of the Battle of Davis’ Crossroads, Bragg wrote Hindman: “The enemy is now divided. Our force at or near Lafayette is superior to the enemy. It is important now to move vigorously and crush him.” If the Confederate attack was to be successful, everything would hinge on Hindman’s initial flanking attack at first light against Negley’s men. At the sound of gunfire, Cleburne’s men would spring into action in a frontal assault of the Union position and crush the enemy. The attack never manifested itself, as Hindman believed that the Federal forces in front of him were much greater than they actually were.

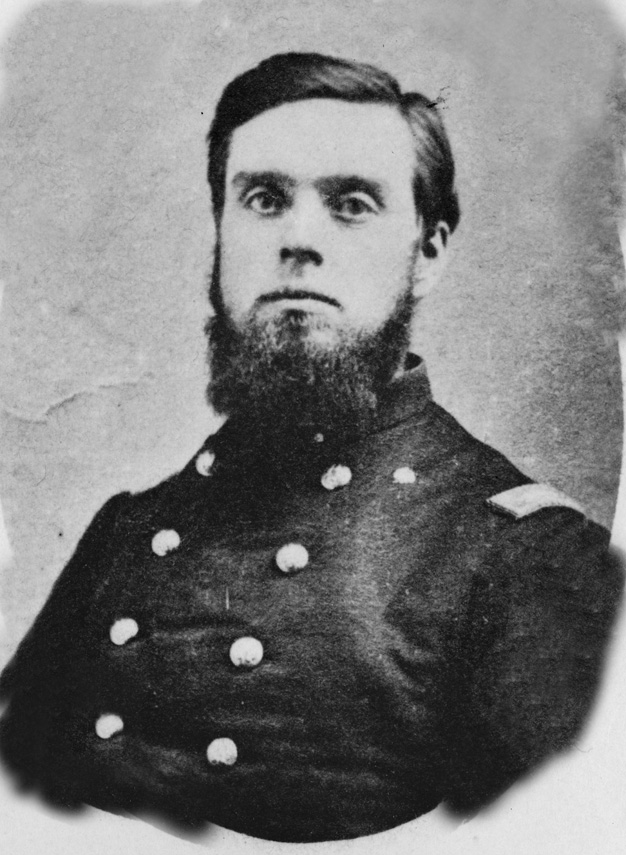

All through the night and into the predawn hours of the September 11, the First Division of the XIV Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird, sped to the aid of Negley’s men. Reaching the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain at dawn, Baird’s men briefly rested and then resumed their rapid pace for an additional nine miles to reach the rear of Negley’s forces. Together, Negley and Baird faced the heart of Bragg’s forces alone, as Thomas’s remaining two divisions were still concentrated west of Lookout Mountain.

Sensing an opportunity still at hand but perhaps slipping away, Bragg once again ordered an attack on September 11, but by the time any concentrated effort manifested itself the Federal forces were already withdrawing smoothly through Stevens Gap. Facing almost certain annihilation, Negley and Baird managed to escape the snake pit that was Davis’ Crossroads. The commander of Negley’s advance guard heaped an abundance of praise on Negley, saying, “The extraction of our division from the environment of Dug Gap by General Negley was to my mind the most masterly piece of generalship I saw during the war.” Thomas was not quite as pleased with the near destruction of two of his brigades, even if they did miraculously escape. “Nothing but stupendous blunders on the part of Bragg can save our army from total defeat,” wrote Thomas.

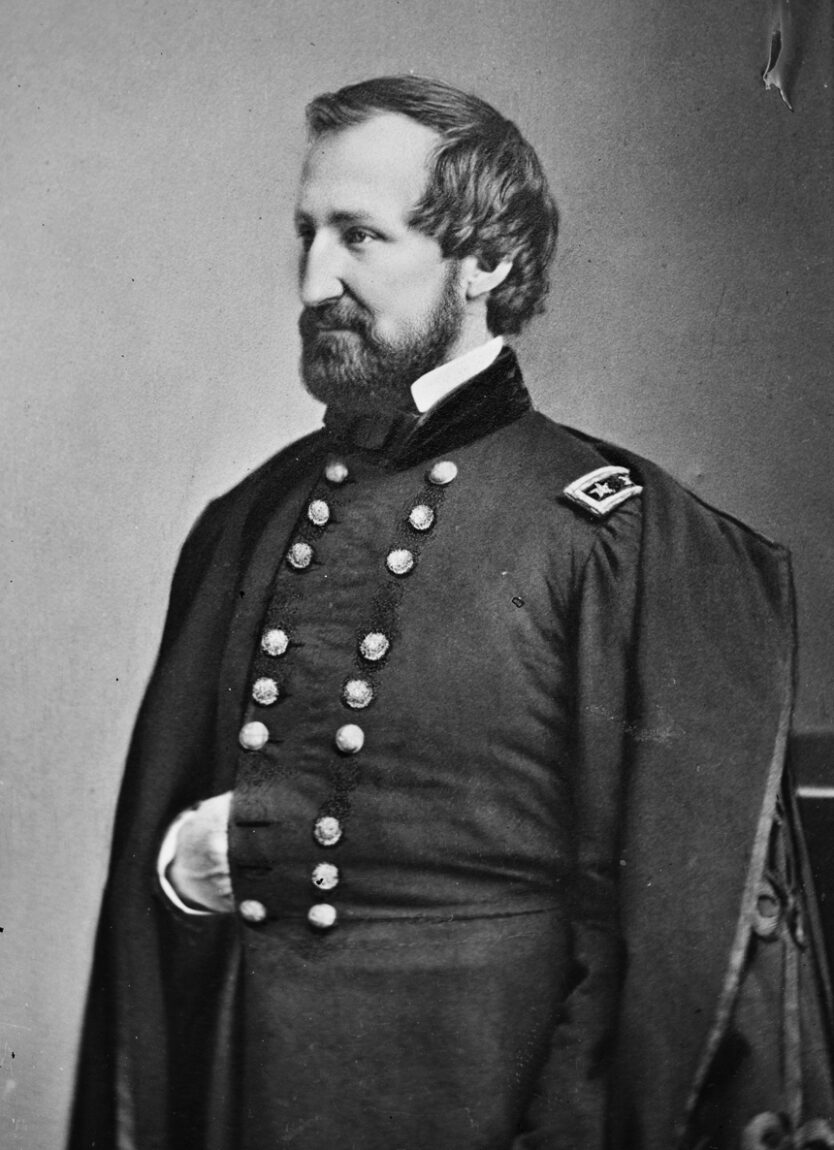

Rosecrans was almost the complete antithesis of Bragg. Trusting, brilliant, and genial for the most part, Rosecrans inspired tremendous loyalty in his men, especially his subordinates. Rosecrans was not without flaws, though. At times, he could become moody and brusque of temper, and he was known to explode in anger without notice, leaving men dumbfounded and hurt only to just as quickly return to his amiable self as if nothing had happened.

On the eve of the greatest battle in the West, Rosecrans was literally one victory away from achieving military immortality. A victory over Bragg in northern Georgia could cut the eastern part of the Confederacy away from the Gulf states, essentially shattering the Confederacy and hastening the war’s end.

Initially, Rosecrans viewed Bragg’s early movements as a retreat and occupied Chattanooga with the extreme left of his army, placing a brigade from Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden’s XXI Corps to guard the important city while ordering all remaining forces to pursue Bragg into Georgia. Everything changed for Rosecrans several days after the Battle of Davis’ Crossroads when he received intelligence, as he stated in his official report of the battle, that “the main body of [Joseph] Johnston’s army [the Department of the West] had joined Bragg, and an accumulation of evidence showed that troops from Virginia [the lead elements of Longstreet’s I Corps, Army of Northern Virginia] had reached Atlanta on the 1st of the month…. It was therefore a matter of life and death to effect the concentration of the army.”

Finally recognizing the danger in which he had placed his army, Rosecrans ordered his forces to consolidate, moving two brigades from McCook’s XX Corps to hold Dougherty’s Gap and sending the remaining men to the defense of Thomas in the center of the line. Rosecrans also ordered Crittenden to move from Ringgold to Lee and Gordon’s Mill and then from Lee and Gordon’s Mill to the southern spur of Missionary Ridge. But on learning that Bragg’s forces were near Dalton and Ringgold, Crittenden was ordered back to Lee and Gordon’s Mill, close enough to support the other corps commanders if necessary.

After the lost opportunity at Davis’ Crossroads, Bragg turned his attention to the Union’s XXI Corps, which was positioned near Lee and Gordon’s Mill and in a similar logistical predicament as Negley’s men were several days earlier. With a distance of about 12 miles separating Crittenden’s forces from Thomas’s forces in the center of Rosecrans’s line and recognizing the proximity of his entire right wing to Crittenden, Bragg ordered Polk and Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker to strike at the lead division of the XXI Corps on the morning of September 13.

Promising additional support from Buckner’s corps, Bragg knew that the attack would be all but foolproof. And just like at Davis’ Crossroads, Polk failed to engage the enemy. Bragg arrived at Polk’s headquarters at 9:00 am and found the lieutenant general getting ready to eat breakfast. Bragg was livid. “Attack for the love of God, attack!” Bragg said to Polk. Citing the need for additional men to ensure success, Polk simply disregarded Bragg’s direct order. By the time Bragg had personally sent his troops forward to pursue Crittenden, the targeted enemy had disappeared behind the protection of Missionary Ridge. Opportunity had once again slipped away from Bragg and the Confederacy.

For the next four days, Bragg and Rosecrans shored up their armies, maneuvering them into positions of respective strength for the inevitable battle that was brewing. With Rosecrans’s army moving northeastward toward Chattanooga on September 17, Bragg came up with a ruse. Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, with two divisions of cavalry, would be sent all the way to the extreme left flank of Bragg’s line. From there they would press the enemy at McLemore’s Cove. This offensive on the Union right wing would divert Rosecrans from Bragg’s real plan, which was to surprise and envelope the Union left flank on the morning of September 18.

The spearhead of Bragg’s surprise attack against the Union left was Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s division, which represented the extreme right of Bragg’s army. Johnson’s men were instructed to move across Chickamauga Creek at Reed’s Bridge at 6 am, turn left, and move toward Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Bragg then ordered Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker’s men to cross at Alexander’s Bridge, farther south along Chickamauga Creek, and unite with Johnson’s men to drive on the enemy’s flank and rear. After Walker’s crossing came Buckner’s men, who were instructed to cross the Chickamauga at Thedford’s Ford, where they were to push the Union men up the stream from Polk’s position at Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Polk was then ordered to join the attack at Lee and Gordon’s Mill, but unlike the other generals he was given multiple options as to where he should cross the Chickamauga, all contingent on the enemy’s positions. Bragg then ordered Hill to cover the left flank of the attack, concentrating on Lee and Gordon’s Mill to ensure that the enemy could not adequately reinforce there.

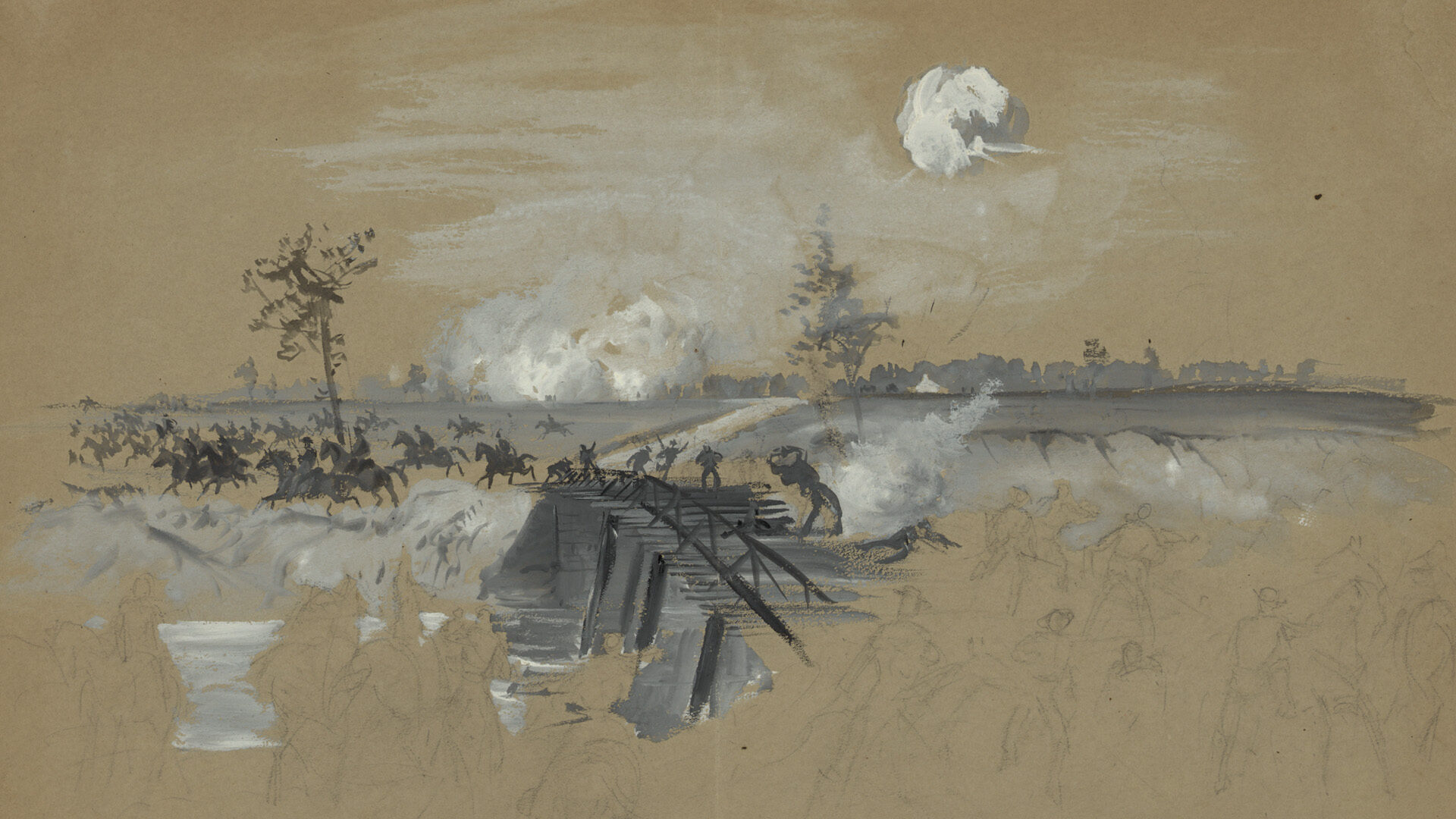

On the receiving end of Johnson’s spearhead strike were members of the Union’s First Brigade, Second Cavalry Division, commanded by Colonel Robert Minty. Around 7 am, Minty was informed by courier that the enemy was advancing in a large force. Minty, determined to meet the enemy, wrote, “[I] strengthened my pickets on the LaFayette road and moved forward with the Fourth Michigan, one battalion of the Fourth Regulars, and the section of artillery, and took position on the eastern slope of Pea Vine Ridge.” Heavily outnumbered, Minty’s men heroically delayed the Confederate onslaught for hours. Around 10 am, Minty noticed a heavy column of dust moving toward Dyer’s Ford, north of Reed’s Bridge, and beyond his reach, which if unchecked could envelop and trap his men. Minty notified Colonel John T. Wilder of the First Brigade (Mounted Infantry), Fourth Division, XIV Corps. Armed with Spencer repeating riffles, Wilder’s brigade answered the call, sending nearly two regiments to support Minty’s position, which was slowly deteriorating as the afternoon wore on.

As Minty and his men were retreating across Reed’s Bridge to their early morning positions near camp, the Confederates, with a force of about 7,000, were in hot pursuit, led by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. At this point, the Confederate commanders recognized that the Union forces were significantly fewer than their own and really opened up on Minty and Wilder, driving both men back toward Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Eventually, reinforcements led by Confederate Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood arrived on the scene late in the day, but by then most of the fighting had ended. Reporting on the day’s events, Minty wrote, “With 973 men, the First Brigade had disputed the advance of 7,000 rebels from 7 o’clock in the morning until 5 in the evening, and at the end of that time had fallen back only 5 miles. On arriving at Gordon’s Mills my men were dismounted, and, together with Colonel Wilder’s brigade and a brigade from General Van Cleve’s division, repulsed a heavy attack at about 8 pm.”

The flanking maneuver against Rosecrans’s left wing failed in its attempt to annihilate Crittenden’s force. It also severely altered Bragg’s overall plan of attack, which was to place his army between Chattanooga and Rosecrans, essentially desiring to fight from the north to the south. Because the flanking maneuver failed, Bragg had to engage the Army of the Cumberland in an east-west position with Chickamauga Creek to his rear. Wilder and Minty bought Rosecrans time to concentrate his army, which he did. Rosecrans ordered General Thomas to relieve Crittenden’s corps by moving the bulk of Thomas’s XIV Corps behind Crittenden and to his left. Crittenden was ordered to secure the LaFayette Road and meet up with Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood, First Division, XXI Corps, at Lee and Gordon’s Mill. McCook was ordered to close his position with General Thomas and protect Crittenden’s right, essentially functioning as reserves. The cavalry force, commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert B. Mitchell, was instructed to guard McCook’s right and to monitor crossings on the Chickamauga.

When night fell on September 18, Bragg was confident that the left wing of Rosecrans’s army was entrenched near Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Bragg had no idea that during the night the XIV Corps was marching northward to relieve Crittenden’s men and to establish battle lines that would stretch as far north as Reed’s Bridge Road. Without this critical information, Bragg planned to attack the left wing of the Army of the Cumberland again with a concentration of his forces in the vicinity of Lee and Gordon’s Mill at dawn on September 19. Bragg failed to consider whether any Union forces were positioned beyond his right flank. At dawn, it occurred to him he ought to find out, and so he sent Forrest to reconnoiter along the Jay’s Mill Road west of the mill. The order would have a profound effect on the course of the battle.

The Battle of Chickamauga actually began in the early morning of September 19, just hours after Bragg’s failed surprise attack on the Union left, when Union Colonel Daniel McCook, Second Division, Second Brigade Reserves Corps, concluded that remnants of an isolated Confederate brigade from Bragg’s failed flanking maneuver remained encamped in the woods near Reed’s Bridge Road and Jay’s Mill, just waiting for sunlight to gather their bearings. Determined to make a name for himself and perhaps earn his brigadier’s star, McCook spent the entire night planning a surprise attack on this isolated and unidentified Confederate brigade. The first point of attack would be to prevent the Confederate brigade from having an escape route, so McCook ordered Lt. Col. Joseph Bingham’s 69th Ohio to take his men and burn Reed’s Bridge immediately. This order was given around 2 am on September 19.

At 6 am, just as McCook was about to give the order to fall in for his early morning attack, McCook was handed a message from Rosecrans to McCook’s commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, ordering Granger to withdraw McCook and Second Brigade, First Division, led by Colonel John Mitchell, from their positions. McCook was devastated but began to withdraw. As the XIV Corps continued to move northward into battle lines, McCook encountered Thomas. Imploring Thomas to rescind Rosecrans’s order, McCook explained the remarkable opportunity that was at hand for the Union Army.

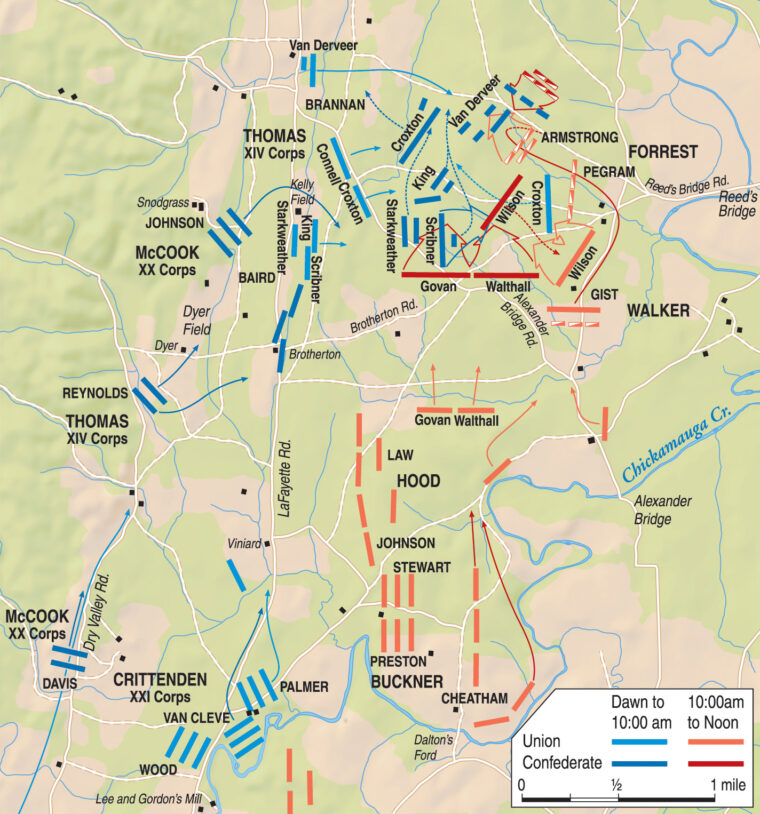

Thomas rejected McCook’s supplications to overturn Rosecrans, but captivated by the idea that there could be a relatively easy move against Bragg, Thomas sent a brigade from his own corps (Colonel John T. Croxton, Second Brigade, Third Division) to investigate the situation. According to Brig. Gen. John M. Brannan, commanding Third Division, XIV Corps, around 7 am, “the Second Brigade, having advanced about three-quarters of a mile toward the Chickamauga, came upon a strong force of the enemy, consisting of two divisions instead of the supposed brigade.” The Union had just stumbled upon Forrest’s four brigades of cavalry, which Bragg had sent northward without much thought, along with two infantry brigades from Walker’s reserve corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Matthew Ector, and Colonel Claudius Wilson in reserve. When Croxton stumbled on these Confederate forces, he allegedly sent back a sarcastic oral inquiry to Thomas asking which of the four or five enemy brigades in his front was the one he was instructed to capture.

Recognizing that this initial skirmish was rapidly escalating into something more significant, Thomas ordered Brannan’s two other brigades, commanded by Colonels Ferdinand Van Derveer and John M. Connell, along with Baird’s entire division, into the fight. This was a significant move because it took the offensive away from Bragg, who assumed that the Federal army would fight from a defensive position. Thomas’s move also interfered with Bragg’s initial plan to engage and envelop the left wing of the Federal army, since Rosecrans was now engulfing the right wing of the Army of Tennessee. Had Bragg stuck with his initial plan of attack, Hood and Buckner would have been able to advance through a major gap in the Union lines between Crittenden’s troops at the mill and Thomas’s men at the Kelly farm. The only opposition they would have met would have been from Wilder’s brigade, which had built breastworks west of the Viniard farm.

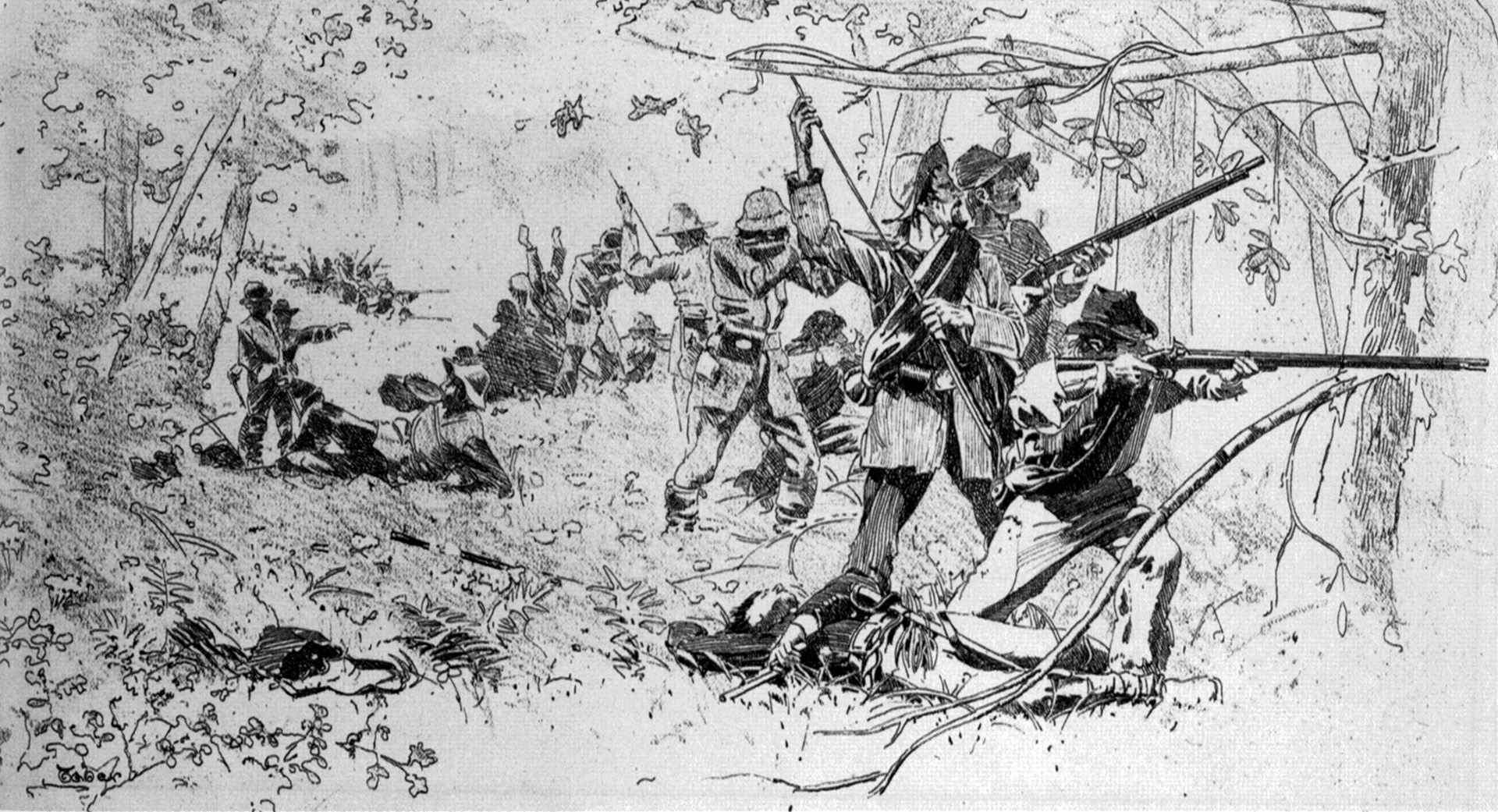

Fighting between Croxton and Forrest was intense, disorienting, and deadly. As Croxton drove Forrest’s cavalrymen back toward Reed’s Bridge Road, Wilson and Ector came up in reserve to defend him. With Ector pressing Croxton from the northeast and Wilson moving in on Croxton from the southeast, Croxton’s men were in danger of being flanked. Croxton shifted part of his line to form a salient against Wilson’s flanking maneuver and successfully drove Wilson back toward Jay’s Mill Road. Recognizing that ammunition was nearly exhausted, Croxton’s men fell back to a natural ridge where they were eventually relieved by Brig. Gen. John H. King, from Baird’s division.

With Federal reinforcements being rushed into the fight, Walker countered with his final division, commanded by Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell. Liddell’s division was divided into two brigades, commanded by Colonel Daniel C. Govan and Brig. Gen. Edward C. Walthall, and an artillery unit under the direction of Captain Charles Swett. Liddell sent Govan and Walthall’s brigades slamming into Baird’s right flank, with King’s brigade and Federal soldiers from Colonel Benjamin F. Scribner’s First Brigade, positioned near King’s right rear, taking the brunt of the assault. Govan and Walthall’s men overwhelmed the Federals, who were unable to adequately respond. According to Baird, “Complete destruction seemed inevitable. Four pieces of Colonel Scribner’s battery were captured after firing 64 rounds, and the enemy, sweeping like a torrent, fell upon the regular brigade before it had got into position, took its battery, and after a struggle in which whole battalions were wiped out of existence, drove it back upon the line of Brannan.” Recalling this day 24 years later, Scribner wrote, “It seemed as though a terrible cyclone was sweeping over the earth, driving everything before it. All things seemed to be rushing by me in horizontal lines, all parallel to each other. The missiles of the enemy whistling and whirring by, seemed to draw the elements in the same lines of motion, sound, light, and air uniting in the rush.”

The near annihilation of Baird’s division by Liddell’s men resulted in the death of approximately 400 Union soldiers with an additional 400 captured or wounded. Baird’s remaining piecemeal force fell back post haste to the relative safety of the LaFayette Road behind Palmer’s Second Division, XXI Corps, and Brannan’s Third Division, XIV Corps. As Walthall and Govan pursued the retreating Federals back toward the LaFayette Road, Brannan’s forces waited to strike.

Men of the First Brigade of Brannan’s Third Division, XIV Corps, commanded by Colonel John M. Connell, were ready for the Confederate onslaught. As Govan’s brigade charged headlong into the pursuit of King and Scribner, Colonel Morton C. Hunter of the 82nd Indiana instructed his men to lie down in the grass and wait for the retreating Federals to pass them by. When Govan’s men were within 50 yards of Connell’s hidden line, Hunter’s men were instructed to rise from the ground and unleash a volley straight into the charging Confederate center. No sooner had the 82nd Indiana fired its murderous surprise volley than the 2nd Minnesota Infantry, under the command of Colonel Van Derveer, rose from the grass in surprise and repeated the collective assault. With artillery support from Battery I, 4th U.S. Artillery (3rd Brigade), Govan’s pursuit of the retreating Federals was checked, and Liddell’s division retreated into dense woods.

The counterattack on Govan and the eventual offensive push against Walker’s reserve corps allowed Federal forces under Brannan and Baird to regroup. Thomas also committed troops under the command of Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson, Second Division, XX Corps, to the fight to support Baird’s right. With renewed vigor, the Federal forces resumed the offensive and relentlessly pursued Walker’s corps back to some high ground to the east. By noon, much of the ground gained by the Confederates during the morning was given back to the Federals as the battle began to transition into a new phase south of Jay’s Mill.

The second major phase of the battle began shortly after noon on September 19, when five Confederate brigades from Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham’s division entered the fight on Walker’s left. Standing against Cheatham’s division were Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson’s Second Division, XX Corps, and Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer’s Second Division, XXI Corps. Dense wooded terrain and irritating, bristly thickets made this portion of the battle especially dangerous and deadly. For two hours, Cheatham’s men assaulted the Union center, exhausting the majority of their ammunition and gaining little ground on the entrenched Federals, who fought back valiantly and eventually charged back. As the Federals advanced upon Cheatham’s men, Confederate Private Sam Watkins, First Tennessee Infantry, from Brig. Gen. George Maney’s brigade, Cheatham’s division described the scene:

“We held our position for two hours and ten minutes in the midst of a deadly and galling fire, being enfiladed and almost surrounded, when General Forrest galloped up and said, ‘Colonel Field, look out, you are almost surrounded; you had better fall back.’ The order was given to retreat. I ran through a solid line of blue coats. As I fell back, they were upon the right of us, they were upon the left of us, they were in front of us, they were in the rear of us. It was a perfect hornets’ nest. The balls whistled around our ears like the escape valves of ten thousand engines.”

With Confederates retreating from the Union center, Rosecrans informed Crittenden that he was “in hopes we will drive them across the Chickamauga tonight.” Union optimism was a bit premature as Bragg committed the divisions of Maj. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, Hood, and Bushrod Johnson to the fight just south of the Brotherton Road. Stewart’s division struck first, slamming into Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve’s Third Division, XXI Corps. Receiving the brunt of the Confederate onslaught were Van Cleve’s First and Second Brigades, commanded by Brig. Gen. Samuel Beatty and Colonel George F. Dick, respectively.

As Stewart’s lead brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Henry D. Clayton, emerged from the dense woods south of the Brotherton Road, the fight continued in earnest to move southwestward. For the next two hours, Clayton battled Van Cleve’s men in an open field with no breastworks or protection of any kind. It was a murderous dual to the death. Though Clayton had only three regiments engaged, his losses were 604 killed and wounded, which amounted to about 200 men per regiment. With losses mounting on both sides, Stewart decided to relieve Clayton’s brigade around 3:15 pm, sending in the division of Brig. Gen. John P. Brown.

Brown’s fresh Confederate brigade overwhelmed the exhausted Federal forces under Beatty and Dick and drove the two Union brigades back toward the LaFayette Road. In the madness of the battle, exploding artillery pieces caused the arid landscape to ignite in a hellish inferno of gray-black smoke, which bought Dick’s brigade a moment to regroup. As the smoke fell all around the charging Confederates, Dick’s brigade managed to fire a single volley into the disoriented Tennesseans, which stunned them to a halt. Noticing the bewilderment of Brown’s men, Dick’s brigade counterattacked.

Dick’s counterattack, which only momentarily halted Brown’s charge, was quickly supported by a well-timed assault from the 75th Indiana, commanded by Colonel Milton S. Robinson of Colonel Edward King’s brigade. The dual attacks by Dick and Robinson sent Brown’s men rushing back into the woods. Palmer, pleased with Robinson’s attack, nevertheless warned Robinson that Stewart would be back, and that he should be ready for him. Stewart did come back, and with a vengeance. Of the 800 men under Robinson’s command, only 50 would be left in fighting condition when the day was done.

The succession of attacks from Clayton’s brigade, Brown’s brigade, and finally from Brig. Gen. William B. Bate’s brigade eventually succeeded in driving Beatty’s and Dick’s brigades back across the LaFayette Road just south of the Brotherton house. Colonel William Grose, commanding Third Brigade, Second Division, XXI Corps, under Palmer was also driven across the Brotherton Road by Bate, who pursued him northwestwardly. Grose, running low on ammunition from the intense fighting, eventually had to retire from the field, leaving the Union center in crisis.

By 4 pm, Confederate forces had regained the field of battle and were beginning to exploit a critical gap in the Union center near the intersection of the Brotherton and LaFayette Roads, when artillery positioned near the northern side of the Union center stopped the Confederate infantry from widening the gap. This delay gave Thomas an opportunity to reinforce the Federal center by shifting Brannan’s division south to fill the dangerous gap. Thomas also sent Baird’s division forward to secure the Federal left flank, once again unifying the Union battle line.

While Federal and Confederate forces remained locked in combat near the Brotherton and LaFayette Roads, Rosecrans decided to commit the division of Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, XX Corps, to the fight near the Viniard farmstead between the Glenn-Kelly and Alexander Roads. Rosecrans hoped that Davis’s division would be able to turn the Confederate flank of Stewart to the northeast, but Davis ran straight into the division of Bushrod Johnson, who promptly attacked Davis’s left wing, under the command of Colonel Hans C. Heg, and drove them back across the LaFayette Road. According to Colonel John A. Martin, commanding Third Brigade, First Division, XX Corps, “The stream of wounded to the rear was almost unparalleled. Still the brigade held its ground, cheered on by the gallant, but unfortunate, Colonel Heg, who was everywhere present, careless of danger … Colonel Heg was mortally wounded; but the remnants of the brigade, falling back to a fence a short distance in the rear, held the enemy in check until re-enforcements came up and relieved them.”

As the brigades of Brig. Gen. John Gregg and Colonel John Fulton (Johnson’s brigade) pressed forward on the Federal left, they became detached from each other with Fulton drifting northward toward the Brotherton field and Gregg moving southwest toward the Viniard farm. Fulton encountered and successfully engaged King’s brigade near the Brotherton field, but Gregg ran into the soldiers of Colonel John T. Wilder’s mounted infantry brigade, who were armed with seven-shot Spencer carbines and were waiting in reserve near the Viniard farm. Wilder’s men unleashed a deadly hailstorm of lead upon Gregg’s surprised brigade, and Gregg himself was severely wounded in the neck. Wavering under such terrible conditions, Gregg’s brigade began to fall back. Brig. Gen. Evander McNair’s reserve brigade was called forward to relieve Gregg, but it also was pressed back as the battle continued to shift south.

Around 3 pm, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood, commanding First Brigade, XXI Corps, was sent into the fight along with Maj. Gen. Phillip Sheridan’s Third Division, XX Corps. For the next 21/2 hours, Hood, Stewart, and Johnson’s men attempted to crush and turn the Federal right flank to no avail in some of the bloodiest combat of the entire Civil War. The optimism emanating from Rosecrans’s camp around midafternoon had evolved into uncertainty as War Department correspondent Charles A. Dana telegraphed Washington that the situation at Chickamauga “now appears to be an undecided contest.”

Dana’s message rang true as Hood and Johnson hunted the brigades of Davis and Wood, mercilessly driving them across the LaFayette Road by dusk. Just as the Confederates were positioning for a crushing final blow to the Federal right flank near the Viniard farm, Wilder’s mounted infantry, once again in perfect position hidden by the wooded geography west of the Viniard farm, opened fire on the charging Rebels and dropped them in their tracks. Wilder wrote in his battle report: “In these various repulses we had thrown into the rebel columns which attacked us closely massed, over 200 rounds of double-shotted 10-pound canister, at a range varying from 70 to 350 yards, and at the same time kept up a constant fire with our repeating rifles, causing a most fearful destruction in the rebel ranks. After this we were not again that day attacked.”

What the Confederates needed near the Viniard farm was reinforcements; they did not receive them. In a puzzling turn of events, the hard-fighting brigade of Irish-born Confederate Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne, who was in the vicinity of Sheridan and Davis and was reportedly crossing Thedford’s Ford around 4:30 pm, was instructed by Bragg to march northward toward the right side of the Confederate line rather than reinforce and potentially turn the Federal right. Bragg critically failed to comprehend the situation on his own left flank, stubbornly adhering to his original plan to position his army between the Federals and Chattanooga. This failure to fluidly adjust to the ever changing nature of real-time battle situations proved costly, especially because Cleburne’s attack was completely unnecessary. Unbeknownst to Bragg, Thomas had already made plans to withdraw Baird and Johnson to more suitable ground along a ridge near the Kelly field for the attack that was surely going to come the next day.

At 6 pm, with approximately 10 minutes of daylight remaining, Cleburne’s division, arranged in a single battle line three brigades wide with Brig. Gen. Lucius Polk (a nephew of Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk) on the right, Brig. Gen. S.A.M. Wood in the center leading the charge, and Brig. Gen. James Deshler on the left, the Confederates entered the Winfrey field. As total darkness swept over the field of battle, Federal and Confederate forces became intermingled in hand-to-hand combat, which occasionally deteriorated into friendly fire. Retreating soldiers from the 6th Indiana, who had just witnessed the death of their commander, Colonel Philemon P. Baldwin, ran straight into Brig. Gen. John Starkweather’s brigade advancing on the enemy. Starkweather’s men mistook the retreating Federals for advancing Confederates and opened fire on them.

On the Confederate side of the fight, Brig. Gen. Preston Smith mistakenly rode up to what he thought was a southern straggler to discipline him, when in reality he was a Pennsylvania sergeant who shot the general off his horse, mortally wounding him. The futility and senselessness of the night fighting became apparent to both sides as losses mounted, and by 8 pm Confederate forces had driven the Federals off the Winfrey field to positions close to where Thomas had ordered them hours earlier. For all their effort, the Confederates were in no position to pursue. The daylong fight had come to an end with inconclusive results.

Rosecrans wrote: “The roar of battle hushed in the darkness of night, and our troops, weary with a night of marching and a day of fighting, rested on their arms, having everywhere maintained their positions, developed the enemy, and gained through command of the Rossville and Dry Valley roads to Chattanooga, the great object of the battle of the 19th.”

Bragg wrote: “Night found us masters of the ground, after a series of very obstinate contests with largely superior numbers.”

Casualties were extremely high on both sides, with multiple sources estimating the number between 13,000 to 18,000 men.

As the night progressed, the temperature plummeted to sub-freezing conditions. With soldiers on both sides so close to each other, campfires were strictly prohibited and sleep became an impossibility. All through the night, the sounds of the wounded and dying echoed through the crisp night air, tormenting the soldiers on both sides and reminding the survivors of the fragility of their own mortality. “The thunder of battle has ceased … but, oh, a worse, more heart-rending sound breaks upon the night air,” wrote an Indiana soldier. “The groans from thousands of wounded in our front crying in anguish and pain, some for death to relieve them, others for water. Oh, if I could only drown this terrible sound, and yet I may also lie thus ere tomorrow’s sun crosses the heavens.”

That night, Rosecrans called a council of war at the Widow Glenn’s house, which included Generals Thomas, Crittenden, and McCook. The prevailing sentiment at the council was that Bragg would either retreat, considering the Confederate assault on September 19 failed to dislodge the defensive position of the Army of the Cumberland, or continue the battle the next morning along the same battle lines. With Thomas urging Rosecrans to strengthen the Federal left, Rosecrans eventually disbanded the midnight council and rode through the lines inspecting the Federal positions, adjusting them for the morning’s impending attack. “Satisfied that the enemy’s first attempt would be on our left, orders were dispatched to General Negley to join General Thomas and to General McCook to relieve Negley,” wrote Rosecrans. With that order, the Army of the Cumberland completed its final preparations for what would become the single worst day in its illustrious history: September 20, 1863.

Bragg, confident that his army had just fought the day against a Federal force consisting of superior numbers, welcomed the late arrival of Longstreet and several of his brigades from the Army of Northern Virginia. With Longstreet’s brigades finally fully united with Bragg, Confederate forces went into the night numerically superior to the Federals, a rare situation in the annals of Civil War history.

As Longstreet and Bragg conferred in their hour-long conference, Bragg informed Longstreet that he was planning to divide his forces into two wings with Polk commanding the right wing and Longstreet commanding the left wing. With Confederates already in position, Polk was instructed to launch a first-light attack on September 20 on the extreme right of their own line and drive the Federals south. Bragg’s orders for Longstreet’s wing were as follows: “Await the attack by the right, take it up promptly when made, and the whole line was then to be pushed vigorously and persistently against the enemy throughout its extent.” With those orders, the Army of Tennessee went into the night confident that the next day’s fight would seal the fate of the Army of the Cumberland and once again restore eastern Tennessee to the Confederacy.

A future article will cover the desperate fighting that occurred on September 20. The day began inauspiciously with a resumption of piecemeal Confederate attacks by Polk’s wing on Thomas’s corps holding the Federal left. Rosecrans had difficulty tracking the exact location of his units, and when an aide erroneously reported a gap in the line, the Union commander ordered Wood to move his division to plug the nonexistent gap. This caused a real gap in the Federal line, and when Longstreet launched his sledgehammer attack against the Federal right, his troops swept through the hole, causing the Federal right flank to crumble. In the chaos, Rosecrans was swept toward Chattanooga with half his army.

Thomas, the epitome of an unflappable commander, fell back to a new position on Horseshoe Ridge, where he rallied the units remaining on the field. The bluecoats repulsed wave after wave of Longstreet’s men before nightfall put an end to the fighting. Thomas’s stand against the enemy on the second day of the battle earned him the sobriquet, “The Rock of Chickamauga.”

The Battle of Chickamauga took everything out of both Bragg and Rosecrans, and neither commander was ever the same again. Rosecrans found himself besieged by Bragg’s forces at Chattanooga, and finding himself unable to break the siege, was eventually relieved of command in October 1863 and replaced by Thomas. Around the same time, Bragg found himself up against the newly formed Military Division of the Mississippi, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. By late November, Bragg had completely lost eastern Tennessee to the Federals, essentially setting the stage for the Atlanta Campaign the following year. On November 29, 1863, Braxton Bragg resigned his command of the Army of Tennessee, and by January 1, 1864, Joseph E. Johnston had taken over.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments