By Louis Ciotola

January and February 1905 were critical months for both the Russian and Japanese empires, which were locked in a war over East Asia that neither of them could sustain. The enormous Russian Empire, assumed by most observers to be militarily far superior to its Asian rival, had failed to quickly subdue Japan. Now Russia was facing increasing domestic turmoil at home, which threatened not only to derail the war effort but possibly to topple the monarchy itself. Meanwhile, Japan, being far smaller than its adversary, was quickly running short of men and resources. With desperation taking hold, the Japanese hoped to achieve a decisive victory. It was a race against time for both empires—a race that only one of them could win. Each would attempt to do so in frozen, desolate Manchuria.

The year began victoriously for Japan, but the triumphs were far from the decisive blow the Japanese were seeking. Still, the capture of Port Arthur freed up valuable troops that could be used to strike a decisive blow in Manchuria, where a large Japanese army sat facing the Russians along the Sha Ho River south of the village of Mukden. The situation was tense. Separated by only a few hundred yards, the opposing armies held tightly to their fortified positions. But despite appearances, both had ambitious plans to attack. Field Marshal Oyama Iwao awaited only the arrival of General Nogi Maresuke from Port Arthur before launching a carefully designed offensive that he hoped would win the war.

His Russian counterpart, Alexei Kuropatkin, had already decided to take the offensive before the fall of Port Arthur. The port’s capture simply forced him to hasten his plans in order to preempt the arrival of Nogi’s army. But the Russian army needed more time to prepare. Kuropatkin had only recently attained supreme command and, although admired by his soldiers, had yet to earn the faith of his officers. Morale was low. Thanks to the vastness of Siberia, supplies arrived either by train via a single track running thousands of miles or after being transported by sail halfway around the globe. Proper winter clothing had reached the troops only a month before. Making matters worse was a divided command. The most divisive individual was political appointee General Oscar Kazimirovich Grippenberg. Upon his arrival in Manchuria, Grippenberg had bragged, “If any of you retreat, I’ll kill you. If I retreat, kill me.” He had no intention of backing such bravado by obediently serving Kuropatkin.

Kuropatkin’s first priority was to slow, if not prevent entirely, Nogi’s arrival. While the Russians were steadily receiving reinforcements, their quality bore no comparison to Nogi’s veterans of Port Arthur. To achieve his goal, Kuropatkin chose to take advantage of Russian cavalry superiority by launching a mounted raid behind enemy lines to sever the Japanese- controlled rail line running north from Port Arthur. If all went as planned, the subsequent Russian offensive would have a greatly increased chance of success.

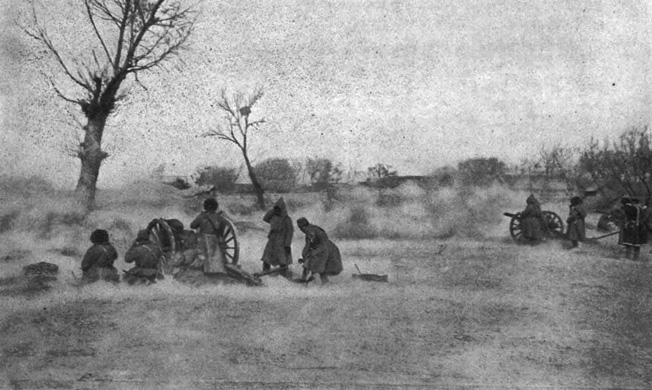

On January 8, 7,500 Russian cavalry and mounted scouts under Pavel Ivanovich Mishchenko set out to conduct the raid. It proved a debacle from the start. Progress was pitifully slow as the Russians stumbled into several Japanese garrisons along their route and pointlessly stopped to engage them. The element of surprise was irretrievably lost. Upon reaching his prime target of Inkou Station, Mishchenko was only able to conduct a brief bombardment before a flood of Japanese reinforcements forced him to attempt a quick frontal charge. The Japanese easily repulsed the attack, and with their position now untenable, the Russians withdrew.

Mishchenko’s raid accomplished nothing except to establish that Nogi had not yet linked up with Oyama. There was only minor communications damage, all of which was repaired within a matter of hours. Observed one phlegmatic Russian commentator, “The result attained by the detachment had not justified our hopes.” In fact, the raid served only to alarm Oyama, prompting him to urge Nogi to hurry to the front.

Nogi had not yet arrived on the scene when Kuropatkin launched a major Russian offensive on January 25. Kuropatkin’s choice of strategy was extremely controversial among his officers. Many wanted to attempt a flanking attack instead of a blunt frontal assault. Chief among the dissenters was Grippenberg, who had been arguing this point of view for weeks. Kuropatkin would not hear of it, fearing that the need to protect an extended flank would merely drain his reserves. Upon being snubbed, Grippenberg sulkily declared that it would be best if the Russian army withdrew entirely. Naturally, this advice too was rejected, but it was enough to spread pessimism among the leadership. General Nikolai Petrovich Linevich, commanding the First Manchurian Army, remarked that there was “little expectation of success.”

The Russians quickly met disaster. Ironically, the initial phase of the attack had been entrusted to the general most opposed to the operation—Grippenberg. The sloppy movement throughout the month of his Second Manchurian Army into its attack positions alerted the Japanese to the Russian strategy well before the offensive began. Furthermore, Kuropatkin’s collection of generals, who had been sent by Czar Nicholas II and his advisers in St. Petersburg rather than selected personally by Kuropatkin, failed to properly coordinate their efforts. A blinding snowstorm and temperatures 25 degrees below zero greatly exacerbated the difficulties.

The resulting fiasco became known as the Battle of Sandepu. The Japanese, already tipped off as to the nature of the Russian strategy, were further aided when Grippenberg prematurely launched his attack of the Russian right. In doing so, he failed to coordinate the offensive with the forces of General Alexander Vasilyevich Kaulbars and, consequently, advanced in isolation. Two of the Second Manchurian Army’s columns attacked the wrong target, which was completely devoid of enemy soldiers, while the artillery mistakenly bombarded Heikoutai rather than Sandepu. Despite the errors, the Russians did manage to gain some ground, but Kuropatkin suddenly got cold feet and declined to commit his reserves. A swift Japanese counterattack quickly erased all the Russian gains. On January 28, Kuropatkin called off the fledgling offensive.

Immediately, fierce arguments erupted over who was accountable for the 14,000 Russian soldiers lost in the catastrophe. It was impossible “to dream of being successful after Nogi’s arrival,” complained Grippenberg to justify his premature actions. He pointed to Kuropatkin’s failure to fully commit the reserves as the principal cause of defeat. Unsurprisingly, Kuropatkin,citing Grippenberg’s clumsy deployment and premature attack, reciprocated by placing the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Second Manchurian Army’s commander. Unwilling to take the blame, Grippenberg claimed illness and petitioned for a recall, which St. Petersburg speedily granted. He would later explain to the czar that Kuropatkin was his real ailment. Kuropatkin, meanwhile, was infuriated by the government’s lenient treatment of Grippenberg and was left with an army badly shaken by defeat and divided in leadership.

Following the battle at Sandepu, the Russian army fell back northward a short distance to Mukden. There, with a front extending over 90 miles, the Russians dug in. Although he took a defensive posture, Kuropatkin remained committed to achieving victory in Manchuria through offensive action. Exactly how such an attack would be conducted in the wake of such a fresh defeat was far from clear.

Oyama, too, had plans to finish affairs in Manchuria with an offensive. The pressure upon him was overwhelming. Despite numerous victories, Japan had reached the limit of its war-making capacity. All of its resources for land operations were now assembled in Manchuria. A decisive blow to end the war triumphantly was absolutely necessary before time told against it. That blow had to be delivered immediately, the Japanese leadership maintained, constantly reiterating the need to achieve a so-called Second Sedan.

To assist him in the ambitious goal of repeating the German victory over the French in the Franco-Prussian War three decades earlier, Oyama had some new tools at his disposal. Following a grueling march through horrific winter conditions, Nogi’s Third Army had at last reached the front, bringing with it the massive siege guns that had so effectively reduced Port Arthur. Fresh reinforcements from Japan, perhaps the last the homeland had to offer, were also on their way, marching up from the southeast under General Kawamura Kageaki. There was no time to lose. Oyama determined that if he was to be successful, it was essential to attack before the coming spring thawed the area’s numerous rivers and provided the Russians with additional natural defenses.

Entirely coincidentally, both the Russians and Japanese finalized their offensive plans on February 19. Kuropatkin’s plan was identical to the one he had formulated at Sandepu. He intended to begin the battle by throwing his right against the enemy left, although this time he would attempt to outflank his opponent rather than simply smash forward. But Kuropatkin’s strategy was based on desperately faulty intelligence. Although he was aware of Nogi’s presence and Kawamura’s approach, he severely misjudged both their placement along the front and the respective strengths of the opposing armies.

Discovering a division of Nogi’s veterans on the Japanese right, the Russian commander falsely assumed this to mean that the entire Japanese Third Army was on the right. In fact, the Third Army was on the left hiding behind the Second Army, completely undetected by the lackadaisical Russian reconnaissance. Even worse, Kuropatkin thoroughly misunderstood the size of Kawamura’s force on the eastern flank. Branded the Fifth Army or the Army of the Yalu, Kawamura’s force was not an army at all, but merely a division and some reservists. The false moniker was a brilliantly orchestrated deception meant to encourage the Russians to believe that the Japanese had many more soldiers at Mukden than they did.

Oyama’s intelligence, as it turned out, was little better. Like his nemesis, Oyama had no idea that his opponent was preparing an imminent attack, even though detected Russian deployments indicated as much. Instead, the Japanese commander trusted in his ability to move more quickly than his enemy and, based on previous experience, assumed that his intricate plan of attack would effectively unnerve the Russian command structure, thus causing it to collapse completely.

“To Decide the Issue of the War”

To achieve his decisive victory, Oyama planned a high-risk, massive double envelopment of the numerically superior Russian army. The movement would be conducted through a series of well-timed actions to disguise his true intentions. First, he would tease the Russians in the east, using Kawamura’s forces to play on Kuropatkin’s unrealistic fears that the Japanese intended to make a dash for the port of Vladivostok. Meanwhile, the weakened Japanese center would maintain a steady but generally weak offensive to draw the enemy away from the real target area in the west. There Nogi would strike, outflanking the depleted Russian right and linking up with Kawamura moving in from the west to complete the encirclement and destroy the Russian army. The center and right were the bait and the left was the hammer.

While supremely confident, Oyama had no illusions regarding his own army’s weaknesses. At a council of war in Liaoyang on February 20, he stressed the need to mount a better pursuit effort than had previously been exhibited in the war. Conscious of Japan’s overall situation, Oyama instructed his generals: “The object of the battle is to decide the issue of the war. The question is not one therefore of occupying certain points or seizing tracts of territory. It is essentially that the enemy should be dealt a heavy blow.” As he spoke those words, initial skirmishing in the east had already begun.

Oyama had his work cut out for him. The Japanese army numbered some 207,000 men to the Russians’ 276,000. The Japanese also faced deficiencies in both artillery and cavalry, having 1,000 guns to the Russians’ 1,200 and only 7,350 cavalry facing 16,000 of the enemy. They did, however, possess a huge advantage in machine guns, with some 250 to the Russians’ 54.

The Russian army ran west to east in a thin line, with its few reserves positioned in the center. Its defenses along the line were formidable enough that many commanders called into question Kuropatkin’s entire offensive-minded strategy. Holding the right flank was the Second Manchurian Army, positioned between the Hun River and the railway leading north to Mukden. Kaulbars had since replaced Grippenberg as its commander. Meanwhile, replacing Kaulbars in the center as commander of the Third Manchurian Army was A.A. Bilderling, whose force sat between the railway and Putilov Hill. In the east, “Siberian Wolf” Linevich retained command of the First Manchurian Army, while to his left, among the rugged hills of the far eastern flank, were two-thirds of the cavalry under General Paul von Rennenkampf.

In the earliest stages of the battle, Nogi’s Third Army still hid behind the Japanese Second Army led by Oku Yasukata, but as Oyama’s plan unfolded it would take its rightful place in the plains on the far left flank. Many among the Japanese command held their breath. They had long feared Nogi to be incompetent, and it had taken all of Oyama’s efforts to retain him in command. Immediately to the right of Oku was Nozu Michitsura, leading the Japanese Fourth Army, while to Nozu’s right was the Japanese First Army under Kuroki Tamemoto. It was Kuroki’s responsibility to support Kawamura’s Fifth Army in the initial deceptive stage of the battle.

The first stage of the battle began on February 23. With the Fushun mines as his objective, Kawamura’s advance against the Russian left began brilliantly, pushing past the enemy outposts and threatening the flank. But the terrain was difficult and the weather atrocious, and Kawamura’s pace soon slowed to a crawl. The Russians possessed a considerable numerical superiority in the east behind entrenchments, and they used their strength to halt the Port Arthur veterans. Nevertheless, Kuropatkin was nervous, triggering a frenzy of activity behind the Russian line as troops from the west were frantically transferred to the east.

Although Oyama was completely unaware why it was so, his strategy was working brilliantly. Russian units raced across the front, thinning their defenses on the plains to waste their energies in the mountains, which actually required far fewer units to create an effective barrier. The counter-productive process thoroughly exhausted thousands of Russian soldiers. Many units traveled well over 50 miles, only to be forced to undertake an immediate return journey, thus making them almost entirely useless due to fatigue. When Kuropatkin ordered the First Siberian Division to detach from the Second Manchurian Army and march eastward, he effectively ended any possibility of launching his own planned offensive. The official cancellation came shortly afterwards.

The weight of the Russian reinforcements halted Kawamura. With a local superiority of two to one, Linevich counterattacked with Rennenkampf’s cavalry, but the attackers quickly ran into the same difficulties that had hampered the Japanese, and the assault achieved nothing. The next day, charging through a blinding snowstorm, the Army of the Yalu attacked again, this time led by the First Kobi Division. Protected by covering artillery fire, the Japanese penetrated to the base of the hills where the Russian entrenchments lay. Only barbed wire prevented a further advance.

The slight Japanese success was due directly to activity in the center. In support of Kawamura, the Japanese First Army launched a bombardment of the Russian positions on the Deniken and Beresnev hills. Following a number of brutal charges, the Japanese captured the heights. Further columns moved to link up with Kawamura, but stiff Russian opposition put a stop to their hopes of creating a united front.

On February 27, Nozu, armed with 11-inch howitzers that Nogi had brought from Port Arthur, began a merciless barrage on the Putilov and Novgorod hills. Although casualties were few, the guns rained shells down on the Russian positions, causing a good deal of torment and prompting one shaken officer to despair, “It is impossible to hold the line now.” But the center did hold. The real problem was farther west, where the situation was destined to be much different.

Although some Russian leaders had long feared an attack on their left, their warnings had gone unheeded. The massive barrage against the Putilov and Novgorod hills convinced Kuropatkin that the main Japanese thrust was still meant for the center. When the real storm broke, he was caught entirely by surprise. By then, more than 40 battalions and 100 guns had moved from the Russian right and center to the left. When Kaulbars faced the main enemy onslaught, he had already been stripped of many of his best troops. The disastrous consequences of the redeployments were felt immediately.

Although the Russians did not detect him for some time, Nogi launched the Japanese Third Army against the Russian right flank in conjunction with the bombardment of the center. The Japanese deceptively kept their infantry hidden behind a cavalry screen during the initial phase of the attack. When Cossacks under General M.I. Grekov encountered the first Japanese, they had no idea that they were facing the full force of Nogi’s army. Regardless, following a brief show of resistance, the Cossacks retreated. Now entirely unhindered, the Japanese advance gained momentum. By the next day, the attackers had nearly outflanked the Russian right wing.

Nogi’s success was in no small part due to another massive Japanese artillery bombardment, this time conducted by Oku against Kaulbars. Oku’s objective was to distract Kaulbars while Nogi completed his encirclement. As in the other sectors, the barrage did little damage to the Russian entrenchments, but it did convince Kuropatkin that the real danger was on his right. Unfortunately for the Russians, that realization did nothing to lessen the confusion within their command. Contradictory orders streamed back and forth, sending units in every direction as the generals struggled to grasp the rapidly changing situation.

The Japanese Third Army advanced virtually uninhibited for three days until a blizzard finally forced it to slow down on March 2. The previous day, Nogi’s flank had been temporarily exposed as it occupied the town of Hsinmintun, but the Russians were in no position to counterattack. Meanwhile, the Japanese were beginning to show some weakness. A lack of supplies and inadequate maps combined with the treacherous weather began to undermine the offensive. Then, too, their enemy at last began to show some competence. Although the Russians had failed to take advantage of any opportunities to disrupt Nogi’s drive, they did manage to change their front in good order.

Unlike the cavalry, the Russian infantry fought courageously, even if its disoriented commanders did little to help their cause. Kaulbars’s men withstood Oku’s advances, although these attacks were limited and only meant to distract from the flank. Nevertheless, Kaulbars and Bilderling, slowly coming to understand their precarious position, began to panic and ordered much of their supplies withdrawn to Mukden. Help, however, was slowly on the way.

Kuropatkin had scrambled together enough reserves by March 2 to order a counterattack against Nogi that stood a chance of turning the tide. He ordered Kaulbars to organize two columns and strike west at Nogi’s flank. M.V. Launitz, left to command the Second Manchurian Army’s front opposite Oku, was ordered to free up additional manpower by reducing the length of his line with a careful withdrawal to the Hun River. After some difficulty this was achieved, but it did little to affect the outcome of Kaulbars’s counterattack. In fact, Kaulbars hardly gave it a chance. When the first column, led by General D.A. Topornin, met stiff opposition, Kaulbars frantically ordered him to abandon the attack. This left the second column under General Alexander Birger entirely in the lurch. Believing he was cut off, Birger withdrew as well.

On March 4, Kuropatkin ordered Launitz to counterattack Oku in preparation for a renewed effort against Nogi. The Japanese, however, were not fooled as the Russians made no attempt to create any type of ruse farther east. Kuropatkin hoped to meet with better luck the second time around thanks to the return of the First Siberian Division to Kaulbars’s command. Furthermore, during the previous 24 hours Nogi’s advance northward had badly extended the Japanese line, leaving it vulnerable to a determined counterattack. By evening, the Japanese Third Army was due west of Mukden. If the Russians were to avoid defeat, the time to take decisive action had come.

Kaulbars launched the counterattack early the following morning. The first strike was led by Konstantin Tserpitski, who brazenly informed his soldiers as they set off: “Children, Russia always conquers. We will conquer now. Advance and sweep these Japanese pagans to hell. There will be no retreat, no coming back.” The more critical assault, however, was conducted by A.A. Grengross in the far north. With the First Siberians under his command, Grengross was ordered to hit Nogi’s exposed flank, which if successful would devastate the Japanese strategy.

Once again, disorder on the command level ruled the day. At the very start of operations, Kaulbars inexplicably altered the plans by transferring men from Grengross to support Tserpitski. The entire strategy was thus compromised. Grengross and the exhausted First Siberians were hung out to dry. Making matters worse, the northern column, rather than hitting Nogi’s flank, ran directly into the spearhead of the Japanese Third Army itself and barely managed to escape encirclement. With everything falling apart around him, Kaulbars ordered a withdrawal. An infuriated Kuropatkin directed all his frustrations at the beleaguered commander of his embattled right wing. “It is necessary to ask the commander of the Second Army if he really fights with an army,” said Kurpatkin scornfully, “and not with a series of warriors for the rest of his troops to watch.”

The Russian Withdrawal

The Russians, at any rate, were out of luck. Kuropatkin, although unwilling to abandon the fight, saw little recourse but to conduct an orderly withdrawal behind the Hun River. Bilderling was ordered to join Kaulbars in that endeavor while Linevich held fast in a desperate effort to prevent a merger between Kuroki and Kawamura. Thus far, the First Manchurian Army had used the terrain to good advantage in stopping Kawamura dead in his tracks. Oyama was determined to get his Fifth Army moving again and directed Kuroki to assist.

Invigorated by the partial Russian withdrawal, the Japanese fiercely renewed their efforts all along the line. On March 6, Oku launched a massive assault against the Second Manchurian Army that further vindicated for Kuropatkin the decision to reestablish himself behind the Hun. In the east, Linevich was no longer able to prevent Kuroki’s reinforcement of Kawamura and the Japanese gradually began pushing the Russians back off the hills. Kuropatkin subsequently ordered Linevich to fall back as well.

As always, however, the most critical theater was the west. By March 7, Nogi had made considerable progress and was close to cutting the railroad north of Mukden, which would sever Russian communications. It was a dire threat that Kuropatkin could not ignore. He was fortunate to have ordered the army’s withdrawal when he did, since it enabled him to now react effectively. Having shortened his lines, Kuropatkin was able to utilize the freed-up manpower to extend his right flank along the rail line north of Mukden and successfully block Nogi’s thrust.

Despite this limited success, the cohesiveness of the Russian army was beginning to break down. Largely unaware of events to their west, Bilderling and Linevich were dismayed by Kuropatkin’s order to fall back. Meanwhile, disorder reigned in the rear. Discipline deteriorated as many soldiers succumbed to drunkenness. Most critically of all, the confusion and the tightly packed conditions made the organized transfer of units virtually impossible, all but eliminating every option short of a total retreat. It appeared that Oyama’s previous assumptions regarding his adversary were proving accurate.

Oyama launched his final attack against the Russians the following day along the entire front. “I intend to pursue in earnest and to turn the enemy’s retreat into a rout,” he declared. Oku, Nozu, and Kuroki advanced in the center, penetrated the new Russian line, and threatened to cut Kuropatkin’s army in two. By midday on March 9, the Japanese First Army, east of Mukden, severed communications between the First Manchurian Army and the rest of the Russian forces. Meanwhile in the west, Nogi finally broke through, destroyed the railroad north of Mukden and moved furiously eastward to link up with Kawamura in an attempt to trap the entirety of the enemy army. The elusive Second Sedan suddenly became a distinct possibility.

For nearly two days, Kuropatkin determinedly held his ground, but by the afternoon of March 9 it was clear that if the army did not retire soon it would be encircled and destroyed. At 6:45 pm he issued the order for a general withdrawal 40 miles north to Tiehling. Less than two hours later, with the order signed, the Russian army commenced its retreat amid a massive dust storm that lasted throughout the following day. The atrocious weather, while impeding the retreat and adding to its confusion, did much to save the beaten forces by fortuitously slowing the jaws of the Japanese pincers.

Before departing, the Russians frantically worked to destroy anything that could be of use to the enemy, including their supplies in Mukden and the rail bridge over the Hun. By now the Japanese center was pushing forward rapidly in their wake. The situation in the rear areas was approaching panic as fleeing Russian soldiers and baggage trains clogged the narrowing escape route, while the dust storm drastically reduced visibility. When Kaulbars overheard an officer inquiring about the whereabouts of the 7th Regiment, the exasperated general, with his arm in a sling due to a broken collarbone, lost his temper. “The 7th Regiment?” he exclaimed. “I do not know what has become of my whole army and he asks me where my 7th Regiment is!”

The rear guard mounted a vigorous and bloody action that saved the rest of the army, even while abandoning most of the wounded in the process. By March 12, most of the Russians were free from danger. Having failed to close the trap in time, the Japanese were forced to content themselves with an indecisive victory and the capture of Mukden. Too exhausted to give chase, they halted, allowing their defeated opponents to fall back peacefully to Tiehling.

Although they ceded the field after nearly being destroyed, ultimately the Russians gave as much as they got. Defeat cost them roughly 70,000 killed, wounded or missing, along with another 20,000 captured. Victory, however, was nearly as brutal for the Japanese, who suffered close to 16,000 killed and 60,000 wounded. The losses, although truly horrific, were losses the massive Russian Empire could absorb—at least militarily. In stark contrast, the losses for Japan were devastating. With men and materials dwindling fast, victories such as Mukden felt more like defeats. Having failed to achieve a decisive blow, the Japanese war effort teetered on the edge of the abyss. It would need an altogether different miracle to take place outside of Manchuria if it was to triumph.

As it turned out, Japan got not one miracle but two. As the fighting in Manchuria raged, revolution rocked St. Petersburg, critically damaging the Russian war effort and threatening the Romanov monarchy itself. Four months later, the Japanese navy accomplished at sea what the army could not on land, utterly obliterating the Russian fleet at Tsushima Strait. In an instant, Russia’s manpower advantage in Manchuria no longer had any meaning. The discouraged czar committed himself to making peace—however humiliating it would prove to be. To all intents and purposes, the Russo-Japanese War was over.

The events of 1905, both political and military, should have finally convinced Russia of the necessity for reform. Unfortunately, no lessons in either area were learned and Russia, completely unprepared, entered WW I in a conflict it had no real interest. This eventually provided the opening Lenin needed and, as they say, the rest is history.