By Al Hemingway

Lieutenant General Hachiro Tagami, commanding officer of the 36th Division, dubbed the Tiger Division, did not like the news he had received from Imperial Army Headquarters in Tokyo. Although his food and ammunition were running low, he was ordered to take the offensive in the Wakde-Sarmi, New Guinea, area.

The Japanese high command had written off the region as a “lost cause” and the new main line of resistance (MLR) had been adjusted 200 miles farther west at the newly formed Biak-Manokwari Line. Tagami was disgusted by the decision, but had to follow orders. He had to “hold out as best he could” against the Allied juggernaut in the New Guinea region.

For several months, while the Japanese were trying to anticipate his next move, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, had used an effective “leapfrogging” strategy. In April 1944, he moved into Hollandia, a strategy that caught the enemy completely off guard. The Japanese high command had fully expected MacArthur to strike at Wewak, a large staging base that possessed two airfields. Instead the supreme Allied leader pushed ahead 110 miles and invaded Wakde Island, just off the northern coastline, for its airstrip. Soldiers from the Alamo Task Force, consisting of the U.S. 41st Division, waded ashore on May 17, 1944, and quickly killed most of the 800-man Japanese garrison defending the island. MacArthur now had the all-important airfield under his control.

From his vantage point atop a hill near Maffin Airdrome just across the bay, Tagami had watchedas his troops were destroyed. He pondered the Americans’ next move. He did not have long to wait.

Initially, MacArthur had opted not to invade Sarmi. It was reported to be “fuller of Nips and supplies than a mangy dog is with fleas.” However, it was decided that Wakde Island “would not be secure without the mainland,” so additional troops were deployed to assault the Sarmi area.

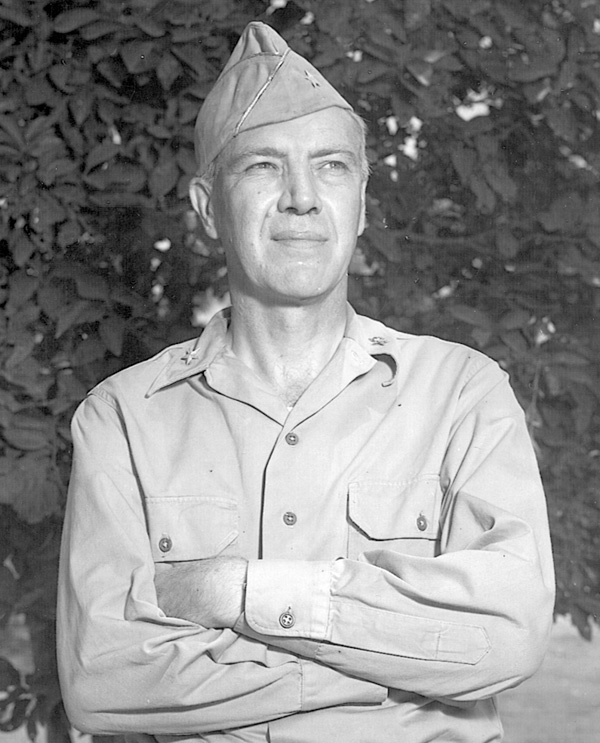

Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, commanding general of the Sixth Army, ordered the Tornado Task Force, camped at Finschhafen, New Guinea, to proceed to the Toem-Arare region. The Tornado Task Force consisted of the 158th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 147th Field Artillery Battalion, the 506th Medical Collecting Company, and the 1st Platoon, 637th Medical Clearing Company.

Originally part of the Arizona National Guard, the 158th was reorganized and sent to the Panama Canal Zone at the outset of the war to provide security, flush out enemy radio broadcasting stations, and test new jungle equipment. While encamped there, they were quickly given the sobriquet “Bushmasters,” after a poisonous snake indigenous to the country.

Many of the soldiers in the Bushmasters were Native Americans from such tribes as the Pimas, Papagos, and Maricopas of Arizona. There were numerous Mexican Americans within the unit as well. Because of this diverse mixture, the soldiers had to bear insults and racial slurs. Most quietly maintained their composure and waited for the day they could prove themselves on the battlefield.

As an autonomous unit, the 158th RCT set sail for the Southwest Pacific in January 1943. After a short respite in Brisbane, Australia, the regiment took part in the occupation of the Trobriand Islands—Kiriwina, Goodenough, and Woodlark.

In January 1944, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were dispatched to Arawe, New Britain, to augment the 112th Cavalry Regiment fighting the Japanese. Reinforced by Shermans from the 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division, the Bushmasters performed well in their initial taste of combat, capturing several enemy strongholds and seizing a 75mm howitzer. When the New Britain campaign ended, the Bushmasters sailed back to Goodenough and Woodlark to refit for their next assignment. That mission would prove to be much more dangerous than the one they had just endured.

On May 21, 1944, the Bushmasters arrived in the Toem-Arare area. The guns of the 147th Field Artillery were quickly set up near the 191st Artillery Group. The howitzers would be needed to provide support for the infantry’s drive to take Sarmi, about 16 miles to the west.

The terrain features in the Sarmi area were not friendly to infantry assaults. In his book, Bushmasters: America’s Jungle Warriors of World War II, author Anthony Arthur explains, “Wakde Island [was] two miles off shore, opposite Toem, the Tor River, which emptied into the sea about five miles west of Toem, and the Woske River, which ran roughly parallel to the Tor, another four miles to the west. Just east of the Woske lay the Maffin Airdrome, and just west of it was the Sawar Airfield. Midway between the two rivers and running parallel with them almost to the sea was Mt. Saksin—not really a mountain but a series of ridges splitting off from the Irier Mountains, with its highest point a peak about 225 feet high. A narrow pass or ‘defile’ separated Mt. Saksin from another slightly lower promontory overlooking Maffin Bay and Maffin Airdrome. The Japanese name for this prominence was Mt. Irier. The Americans would call it Lone Tree Hill.”

The Bushmasters’ task would not be an easy one. The riflemen had to traverse several rivers and a series of ridges and hills occupied by a seasoned unit, the 36th Division. Furthermore, Brig. Gen. Edwin D. Patrick, the newly appointed leader of the Tornado Task Force, which numbered about 5,000 men, had been grossly misinformed about the number of enemy troops defending the approach to Sarmi. Patrick had been told there were approximately 6,500 Japanese there, but this intelligence was wrong. In reality, over 11,000 enemy soldiers were dug in and ready to do battle.

While the 158th RCT was preparing to strike a numerically larger force, Tagami was planning an attack of his own. Realizing the airfields would be the targets of an American attack, Tagami formed the Yuki Force, consisting of 4,000 men, to guard the hills to the south and southwest of Maffin and Sawar Airdromes. He then established the Yoshino Force, under the leadership of Colonel Naoyasu Yoshino and composed of two battalions from the 223rd Infantry with attached artillery. In addition, Tagami recalled his Matsuyama Force; it was headed by Colonel Soemon Matsuyama and had been sent toward Hollandia to harass and prevent any further westward movement of Allied troops toward Sarmi.

These two groups would act as a pincer and assault the Toem-Arare beachhead in a double envelopment. If successful, they would obliterate the supply stores and headquarters of the Tornado Task Force, leaving the Bushmasters with no food, ammunition, or medicine.

Unaware of Tagami’s plan to hit the supply depot at Toem-Arare, Colonel Prugh Herndon, the Bushmasters’ commander, sent Company L, 3rd Battalion, 158th RCT across the Tor River to begin offensive operations against the firmly entrenched Japanese in the region. Not long after wading across the waterway, Company L was met by withering machine-gun and automatic weapons fire from the beach. Companies K and L, aided by the 81mm mortar section of Company M, quickly sent the Japanese scurrying from their positions as they returned fire.

Captain Clarence Fennell, commanding Company L, lost four men killed and 30 wounded at the end of the first day of fighting. Fennell acknowledged that the enemy had fought hard and put up a dogged resistance against the Americans. He concluded that if this was an example of the ferocity in defending Sarmi, it was going to be a long, bloody struggle. Fennell would soon see how right his conclusions were.

The 3rd Battalion stepped off on the attack the following morning, rounds from the 105mm guns (howitzers) of the 147th and 218th Field Artillery screeching overhead to give the advancing infantrymen some much-needed support against the enemy’s barricades.

When a few errant shells struck within Company L’s staging area, resulting in friendly casualties, the 3rd Battalion commander decided to halt the barrage. Unbeknownst to him and the others, this was not friendly fire, but Japanese artillery. Because they were relatively new to combat, the majority of the soldiers did not realize it was enemy fire.

Despite this setback, the assault began with both Companies K and L abreast and Company I in battalion reserve. Company K soon met stiff enemy resistance, and flamethrowers and tanks from the 27th Engineers were called upon to help dislodge the Japanese from their fortifications. When the infantrymen finally overran the enemy entrenchments, they nabbed several Nambu machine guns.

While Company K was embroiled in heavy combat, Company L ran headlong into its own predicament. When riflemen tried to cross the Trifoam River just west of the village of Maffin #1, they were greeted with a storm of automatic weapons fire. With the infantry unable to move forward, four tanks from the 603rd Tank Company rushed to the scene to assist the pinned-down soldiers.

Without warning, the fanatical Japanese poured from the jungle screaming “Banzai! Banzai!” Enemy troops from the 3rd Battalion, 224th Infantry and a company from the 223rd Infantry rushed the Bushmasters. The riflemen began picking off the charging horde while the machine-gun sections wasted no time letting loose a stream of fire into the enemy’s ranks. Japanese infantry began toppling, and one of the first to fall was a saber-waving colonel by the name of Kato.

During the chaos, Japanese gunners manhandled a 37mm antitank gun into position. Before the piece could be destroyed, it knocked out three of the tanks supporting the Bushmasters. Confronted with the combined American firepower, the assault soon fizzled, and the Japanese fell back into the jungle.

By nightfall, a gap began to appear between the Bushmaster companies. Herndon wasted no time in putting in the 1st Battalion to plug the hole. The 158th had advanced just to the north of Maffin #1 and secured a 1,000-yard perimeter, but the cost was high. The unit had suffered 28 killed and another 75 wounded. With daytime temperatures soaring over 100 degrees, there were also many cases of heat exhaustion.

On the morning of May 25, with a blistering sun overhead, the Bushmasters once again advanced to drive the Japanese from their bulwarks. The newly arrived 1st Battalion crossed the Trifoam Bridge and occupied the hamlet of Maffin #1. As Companies A and B pushed onward, Company D machine gunners provided the extra support to keep the enemy at bay while the movements were being completed. As darkness fell, the 1st Battalion had secured both a peninsula and a pier.

Under cover of darkness, the enemy relinquished its positions and began to occupy other defenses on Lone Tree Hill. A threatening mountain, Lone Tree Hill was 175 feet in height, extending over 1,200 yards from north to south and another 1,100 yards from east to west. It was dubbed Lone Tree Hill due to the one tree that appeared on the terrain maps of the Tornado Task Force. In actuality, the hill was covered with a substantial rain forest and thick jungle undergrowth.

To attack up its northern slopes would prove unfeasible, due to a sharp drop into Maffin Bay. On the eastern side of the mount was a stream the Bushmasters named the Snaky River because of its many curves. A road cut through a narrow defile, forming the two “noses” of Mount Saksin, which was much the same as Lone Tree Hill but about 100 feet higher.

Tagami’s engineers had not been idle. They had toiled to create a labyrinth of caves, machine-gun nests, mountain guns, and observation posts throughout Lone Tree Hill. Other positions were built in the tops of the coconut trees common to the area and were resistant to most air and naval gunfire.

Satisfied with his men’s construction efforts in transforming Lone Tree Hill into an impregnable fortress, Tagami moved his headquarters to the summit of Mount Saksin. He realized this would be a major battle. Not only did his men protect the airdromes, but they also “defended the only escape route from New Guinea for the Japanese Army.”

When the 158th RCT began to encounter even stiffer opposition on its drive toward Lone Tree Hill, Colonel Herndon became convinced that the number of enemy he was facing was much greater than division intelligence had led him to believe. Herndon informed division command of this, but they nonetheless ordered him to seize the objective by the next day.

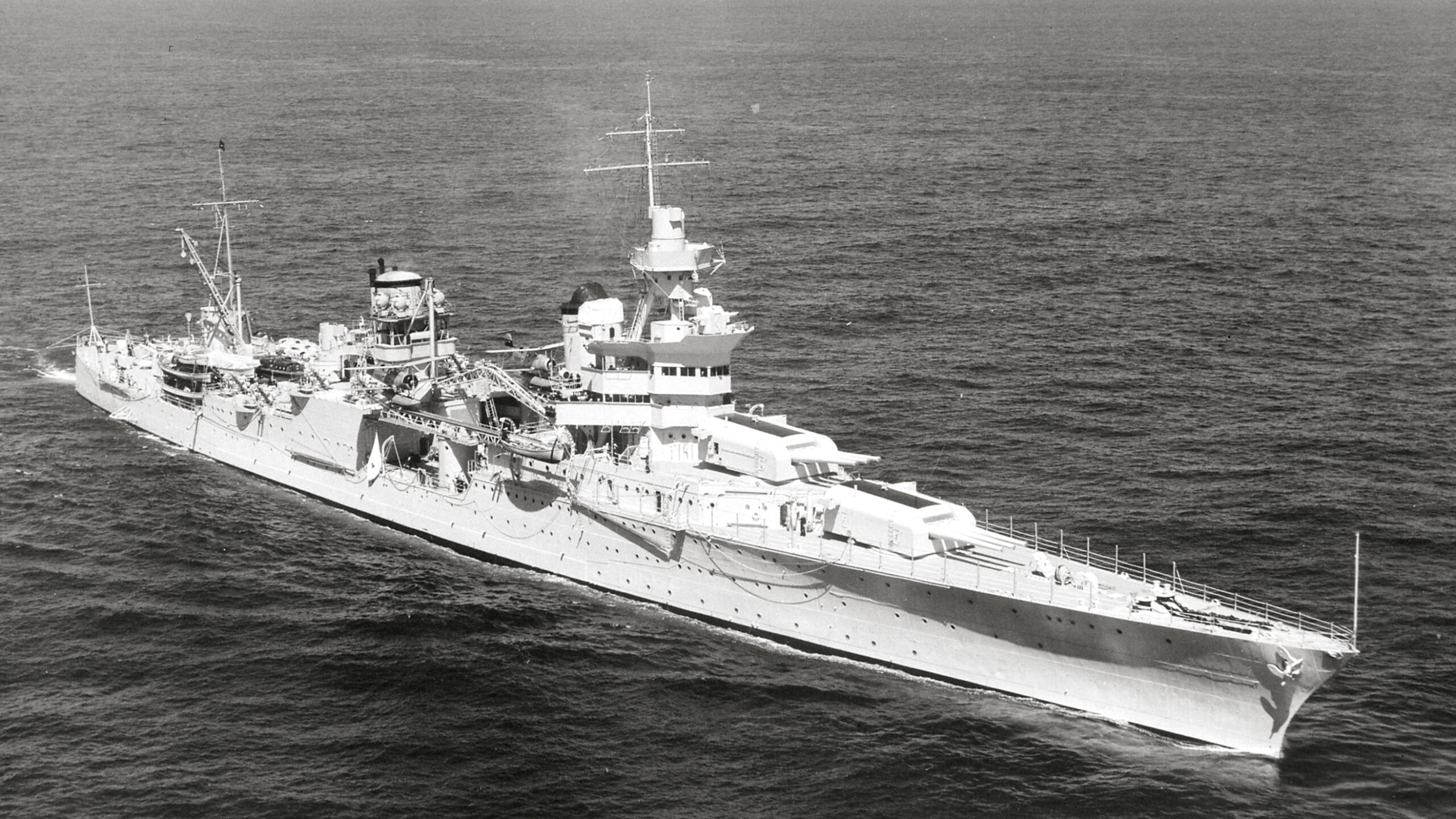

As dawn broke over the sweltering New Guinea jungle on May 26, two destroyers in Maffin Bay let loose a bombardment on the northern face of Lone Tree Hill. The howitzers from the 147th Field Artillery, repositioned at Maffin #1 to assist in the attempt to capture the mountain, began their firing missions as well.

Company B was the vanguard of the attack. The riflemen pressed forward toward the tiny hamlet at the eastern end of the pass and the banks of the Woske River, west of Lone Tree Hill. Unfortunately, the artillery and naval gunfire subsided and there was a 10-minute pause before the Bushmasters began their advance. This allowed the Japanese time to regroup and set up their automatic weapons before the Americans reached them.

As the Bushmasters made their way to the southeast corner of Lone Tree Hill, the Japanese hit them with an intense wall of machine- gun and automatic weapons fire. Despite this, the 158th RCT gained over 1,000 yards. Company B’s reconnaissance platoon managed to escape an ambush and reported to Herndon that the Japanese were well hidden and skillfully dug in throughout the mountain. Still, Task Force Tornado headquarters told Herndon to keep hitting the enemy at Lone Tree Hill and Hill 225.

Knowing it was futile, Herndon nonetheless prepared for the assault the next day. He sent the 1st Battalion into the narrow defile, while the 2nd Battalion struck at Hill 225. The following morning naval gunfire tore into the pass and 81mm mortars crashed into the slopes to soften the Japanese positions. Miraculously, Companies E and F did reach what they thought was Hill 225, but it turned out to be Mount Saksin, which was over 700 yards to the east.

Meanwhile, Company B was getting hit hard from enfilading fire between Hill 225 and Lone Tree Hill. Under a withering barrage, the soldiers withdrew. By nightfall of May 27, almost 300 men of the 158th RCT had been lost. “These Japanese soldiers were among the fiercest fielded by the enemy,” wrote Anthony Arthur, “veterans of years of fighting in China and Malaya. Many of them were six-footers from the northern island of Hokkaido. They were well led, familiar with the terrain, and more than willing to die for their emperor.”

At Sixth Army Headquarters in Hollandia, General Krueger was being “pressured” by MacArthur “to end this New Guinea thing.” The Allied commander was poised to strike at Biak Island, Noemfoor, and the Vogelkop to “slam the door” on the remaining enemy troops in New Guinea and let them “die on the vine.”

Two battalions from the 163rd Infantry were ready to invade Biak. This left the Toem-Arare beachhead, where the supplies were situated, understrength. As a result, General Patrick sent word to Herndon to send one of his battalions to assist in defending the strategic area.

By the 28th Herndon had had enough. He telephoned General Patrick and told him he was withdrawing to the eastern bank of the Trifoam River and establishing a defensive perimeter. Patrick did not approve and responded: “Do you still feel that you don’t want to do it?” Herndon responded in the affirmative; he did not want to pursue the attack. He felt his men had suffered enough. Finally, Patrick reluctantly gave his approval. For his actions Herndon was relieved of command and Colonel Earl “Bulldog” Sandlin, a hard charger, took the reins.

As he departed, Herndon could not help but cry. He had been with the Bushmasters for over 20 years. Even Krueger was deeply hurt by the decision. The Sixth Army commander was planning to promote Herndon to the rank of brigadier general following the operation. After putting Herndon’s stars in his desk drawer, Krueger closed it and muttered: “He lost them at Lone Tree Hill.”

Sandlin now had the 2nd and 3rd Battalions encamped on the east bank of the Trifoam River enduring nightly enemy probes and sporadic artillery fire from the Japanese 70mm and 75mm guns. The 1st Battalion had moved to Toem-Arare to help the 163rd Infantry defend the supply dump.

And defend it they would. But the Bushmasters at Arare were not aware that the Yoshino and Matsuyama Forces had eluded the perimeter defenses near Lone Tree Hill and were moving toward the Arare beachhead to attack and annihilate them.

Unfortunately, the perimeter defenses at Toem-Arare were “strung out along the beach like a string of pearls,” according to one American officer. In all, 21 separate strongholds were scattered along the shore. It was a mixed bag at best. Antiaircraft units had positioned their 40mm and .50-cal. machine guns to protect the area from attacking enemy aircraft. The 202nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion had half a dozen emplacements spread around the Tor River and Tementoe Creek. These gun positions were over 5,000 yards away from each other.

On the morning of May 29, the weary 1st Battalion, 158th RCT arrived at the beachhead at Toem-Arare. Exhausted after nearly a week of nonstop combat at Lone Tree Hill, the soldiers went about preparing their foxholes and settling in for the night. To them, this was heaven. Before the day was over it would instead become a living nightmare.

The Yoshino detachment, traveling only by night, had secretly made its way to the supply depot where it prepared to push the Americans into the sea, destroy their supplies, and kill the remainder of the Bushmasters still encircling Hill 225 and Lone Tree Hill.

As dusk fell, the Japanese became more brazen in their movements. Sergeant Jay Morago’s machine-gun section huddled in its foxholes listening to the names the Japanese were calling them. Insults such as “Yankee Dog, tonight you die!” punctuated the dark night. Morago chuckled because he was a full-blooded Pima Indian. The thought of himself as a Yankee was amusing. Suddenly, he heard the sound of gunfire in the distance. His squad prepared for the inevitable assault.

What Morago had heard were the sounds of the Japanese overrunning No. 6 gun position of Battery B, 202nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion. Then, No. 8 gun pit also fell. The Japanese managed to seize a .50-cal. machine gun and a multiple .50-cal. mount. They also damaged two 40mm cannon and electrical and communications equipment.

About 2:30 am, the main Japanese thrust occurred in the center of the American line. Tying grenades together, the enemy began throwing them at the Bushmasters in “sling- shot” fashion. Japanese “knee mortars” began landing with terrible accuracy, and automatic weapons fire picked up in intensity.

The American .30-cal. Browning machine guns soon began to overheat and then jam. Morago picked up a carbine and shot three enemy soldiers. When a grenade fell among the men, Pfc. Jack Carson quickly smothered it with his body. The ensuing blast killed him instantly, but he saved the lives of his fellow Bushmasters. For his outstanding bravery, he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Before daybreak, elements of the 163rd Infantry were rushed in to assist the Bushmasters. By dawn, the enemy attack had been beaten back. As the battalion officers walked the battlefield to assess the situation, they were surprised to see that the Japanese had dynamite taped to their bodies, making them human bombs. Many of them also had their mouths taped shut to prevent them from crying out in pain if they were hit. In all, 52 dead Japanese infantrymen were counted. The Bushmasters had lost 12 killed and 10 wounded.

The 158th RCT could have fared much worse. The Yoshino and Matsuyama Forces had a communications breakdown and, thus, the combined attack on the beachhead never materialized. The survivors from both enemy groups reorganized and rejoined Tagami’s main force defending Lone Tree Hill and Hill 225.

Realizing that the Japanese were in the area in much greater strength than first thought, General Patrick immediately went about reorganizing the Toem-Arare defenses. Additional reinforcements arrived to renew the attack on Lone Tree Hill; the 6th Infantry Division and the 20th Infantry began arriving to add punch to the upcoming assault.

By June 5, the push was on to take Lone Tree Hill. Tank-infantry teams worked closely together to eliminate enemy vpillboxes. Still, it was hazardous duty. Riflemen had to crawl on their stomachs and toss grenades into the firing apertures and flamethrower tanks ignited the fortifications. Awaiting riflemen cut down any Japanese soldiers attempting to escape. It was slow going as combat engineers, armed with TNT, destroyed the numerous caves that dotted the hillsides. After a month of savage combat, the Lone Tree Hill-Mount Saksin-Hill 225 area was officially declared secure.

When it was finally over, the Japanese 36th Division had been nearly destroyed. They had suffered nearly 4,000 casualties, with an unknown number dying in caves or committing suicide to avoid the humiliation of surrender. General Tagami’s body was never recovered.

With the seizure of the Lone Tree Hill area, MacArthur could now utilize the Maffin and Sawar airstrips for further offensive operations against the Japanese. Almost immediately, bombers from the Fifth Air Force began hammering enemy strongholds on Biak, Noemfoor, Vogelkop, Halmahera, Morotai, and the Palaus.

All of this success had come with a big pricetag. The Bushmasters had sustained nearly 350 killed, wounded, and missing in the campaign. Regardless, their first major combat assignment had been a resounding success. They had faced and beaten some of the best Japanese soldiers in the field. They had certainly earned the admiration and respect of General Douglas MacArthur and, more importantly, their fellow soldiers.

A U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War, Al Hemingway writes frequently about the island fighting that took place during World War II in the Pacific.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments