By Allyn Vannoy

Flight Petty Officer Saburo Sakai was anxious to engage the American carrier pilots for the first time, testing his skills against what he had been told were the best opponents he would come up against. The adversaries would meet in the skies above the island of Guadalcanal.

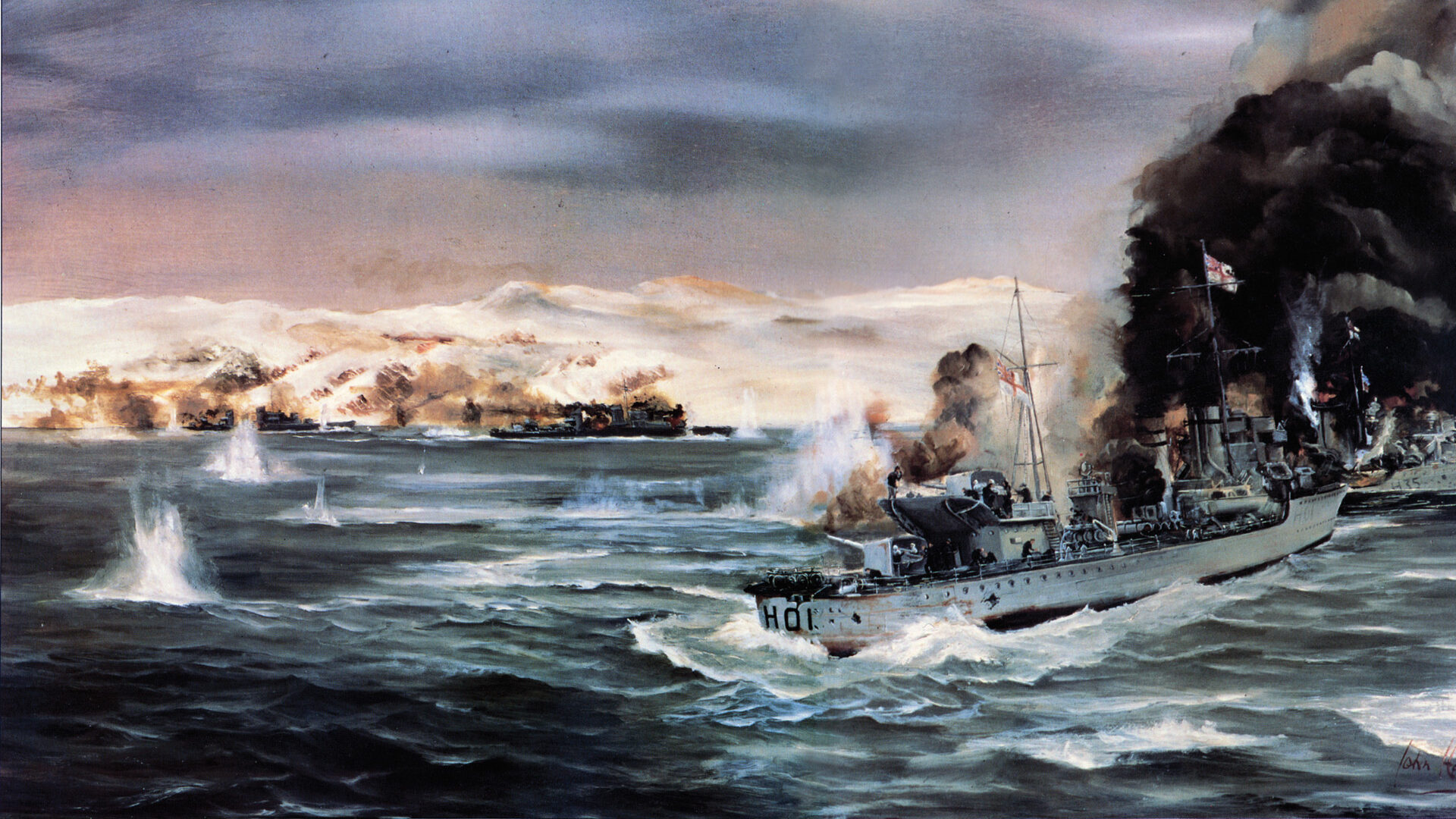

During the American landing operations on August 7-8, 1942, Japanese naval aircraft based at Rabaul attacked the amphibious forces several times, setting fire to the transport USS George F. Elliott, which sank two days later, and heavily damaging the destroyer USS Jarvis. In the air attacks over the two days, the Japanese lost 36 aircraft, while the U.S. lost 19, both in combat and to accidents. One of the Japanese aircraft was flown by Sakai, a veteran of combat operations over China, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and New Guinea. The spirit of the Samurai was in his blood, as the fighting over Guadalcanal would prove.

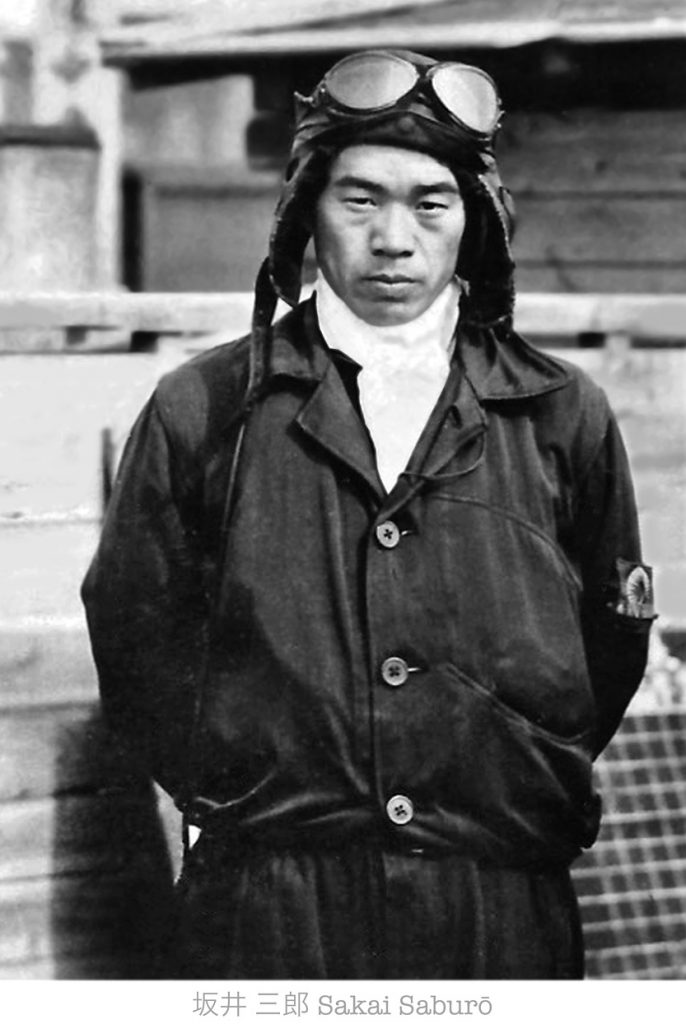

Saburo Sakai, flight petty officer, 1st class, of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), later promoted to lieutenant (j.g.), was an ace fighter pilot. Born in Saga Prefecture in the northwest of the island of Kyushu, the third of four sons (his given name means “third son”), Sakai was 11 when his father died. Adopted by his maternal uncle, he attended high school in Tokyo; however, Sakai failed to do well and was sent back to Saga.

In May 1933, at the age of 16, he enlisted in the IJN. After completing basic seaman training, Sakai served aboard the battleships Kirishima and Haruna. In 1937, he was accepted into pilot training. Though graduating as a carrier pilot, he was never assigned to aircraft-carrier duty, but to a shore-based naval-aviation unit. He flew combat missions piloting a Type 96 Mitsubishi A5M fighter during the Second Sino-Japanese War and was wounded in action. Later, Sakai was selected to fly the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter.

When war broke out in 1941, Sakai participated in the attack on U.S. installations in the Philippines as a member of the Tainan Air Group—a fighter-aircraft and airbase-garrison unit of the IJN. On December 8, 1941, as part of a flight of 45 Zeros, Sakai participated in an attack on Clark Field, north of Manila. In his first combat against the Americans, Sakai shot down a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighter and destroyed two Boeing B-17 bombers on the ground. On the third day of the fighting, Sakai claimed to have shot down a B-17 flown by the legendary Captain Colin P. Kelly, although he was not officially credited.

Early in 1942, Sakai was transferred to Tarakan Island in Borneo for operations in the Dutch East Indies. During the Borneo campaign, Sakai achieved 13 victories before he was grounded due to illness. In April, Sakai was transferred to Lae, New Guinea, where, over the next four months, he scored the majority of his victories flying against American and Australian pilots based at Port Moresby. By August, Sakai was a section leader, and his air group was transferred from Lae to Rabaul, New Britain.

On the morning of August 7, the men of Sakai’s fighter group were informed that at 5:20 am that morning, enemy forces had landed at Lunga, on the island of Guadalcanal, and had also attacked Tulagi, where 10 flying boats and 10 seaplane fighters, part of the Yokohama Air Corps, 25th Air Flotilla had been based. The entire flying-boat flotilla had been destroyed, and once a flight route had been plotted, the fighter pilots were to attack the enemy forces near Guadalcanal.

Sakai remembered, “This morning our usual mission of fighter patrol, attack against (Port) Moresby or air-to-air combat, was to be replaced with a special attack…. The pilots spoke with enthusiasm to each other. ‘Maybe today we’ll have a big fight,’ one said. ‘I’d like to get a kill,’ another added. Our pilots were understandably eager to engage the enemy fighter planes in combat. The results obtained with our Zero fighters against enemy airplanes had been so amazing that often the enemy appeared openly to fear our arrival and, often times, had even refused to join combat.”

As the pilots waited for details of the day’s operation, Captain Masahisa Saito, the unit’s commanding officer, Yasuna Kozono, the air officer, and Lieutenant Commander Nakajima gathered around a large map to plan the day’s mission.

After the pilots had been ordered to fall-in, Captain Saito informed them that a powerful enemy invasion force under heavy cover had attacked Lunga Roads, Guadalcanal, at the southern end of the Solomon Island group, where Japanese engineers had been constructing an airstrip.

Sakai recalled Saito’s words: “Our naval forces operating in the Rabaul area have been ordered to engage the enemy immediately, in full strength, and to drive back the American invasion forces at any cost. Our fighter-plane units have been ordered to escort the land-based medium bombers, which will attack enemy ships. Certain fighter groups will precede the bombers and their escorts into the battle area as challenging units, to draw off the American fighter planes. You will be taxing your airplanes to the utmost, and I want every pilot to take maximum precautions to conserve fuel.”

At a distance of almost 560 nautical miles from Rabaul to Guadalcanal, it would be the longest mission they would be called upon to fly. There was disbelief among some of the pilots that they would have to fly such a distance, engage the enemy, and then fly back to Rabaul.

Before they climbed into their Zeros, Lieutenant Junichi Sasai, Sakai’s immediate superior, made a final address to the pilots: “The American fighters over the Guadalcanal area are known to have come from aircraft carriers supporting the invasion. They are probably regular American navy fighters, not army planes, brought in especially for this attack. This is the first time we will be meeting American navy fighters.” Then he added, “Be careful, and never lose sight of my plane.” Lieutenant Sasai’s brother-in-law, Lieutenant Commander Yoshio Tashiro, was a flying-boat officer stationed at Tulagi. His death was later confirmed.

The realization that he would be flying against U.S. Navy pilots excited Sakai. “I had been anxious to meet American carrier pilots for a long time,” he later said. “Now my chance had come! I had been flying fighters for six years and had more than three thousand hours in the air. I had participated in our attacks on the Chinese inland cities of Chungking (Chongqing), Chengtu (Chengdu), Lanchow (Lanzhou), and others in the Sino-Japanese Incident. Since the outbreak of the Pacific War, I had fought in the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. So far I had shot down fifty-six enemy planes, and was one of the leading aces of all Japanese naval fighter pilots. But I had never met any carrier planes.”

Sakai instructed his two wingmen, Hatori and Yonekawa, to exercise caution and to never break away from him, no matter what.

At 8:00 am, 17 Zeros took off, organizing themselves into three-plane formations as they climbed and headed south toward the Solomons. Some of the fighters moved into position above and behind the 27 Mitsubishi G4M1 bombers, nicknamed “Bettys” by the Allies, they were directed to escort. Others flew ahead of the bombers as part of the “challenge unit” intended to clear the way for the Bettys. The bombers rose to an altitude of 15,000 feet. Sakai was the flight leader of the second section of the second fighter squadron. He was disturbed by the fact that the bombers were carrying bombs rather than torpedoes, the usual armament for attacking shipping. He realized, given past experience, the problem of trying to hit moving targets from high altitude.

As they flew south over New Georgia, the Japanese aircraft crossed the Russell Islands at 20,000 feet. Just before noon, some 50 miles from Guadalcanal, they sighted Lunga Roads. Sakai recalled, “There were scattered clouds at about thirteen thousand feet, but above and below that level the sky was absolutely clear. We searched Lunga Roads carefully and gradually distinguished the shapes of the enemy ships in the area. The water seemed covered with vessels. I had never seen so large a convoy before, although I had flown on many occasions over Japanese troopship fleets during our invasion operations. I couldn’t help admiring the men below me, even though they were enemies.”

At that moment the fighters of the challenge unit, preceding the main body by several minutes, began tangling with American fighters. Sakai spotted signs of a dogfight, bright flashes and streaks of smoke trails as aircraft fell earthward. But in moments the sky was again clear of swirling aircraft, and the bombers started into shallow dives toward the American ships.

Then, without warning, six enemy fighter planes appeared, diving through the bomber formation. Sakai identified them as Grumman F4F Wildcats. Sakai started to go after them but then recalled his commander’s instructions and climbed back to resume his position.

Sakai described the bombing effort: “The missiles hurtled down toward the enemy ships and the bomb spread successfully covered the enemy convoy, but only a few of the bombs appeared to hit any ships [none were actually hit]. We could see about eighty large ships in the enemy fleet; countless landing barges were heading for the beach, the brilliant white wakes on the water surface having the appearance of brush strokes of a giant but invisible artist. Although it had been only five or six hours since the enemy invasion forces had stormed in to land on Guadalcanal, what appeared to be enemy antiaircraft fire could be seen coming from guns on the island. I was amazed at the ability of the enemy to place his antiaircraft weapons on shore so rapidly. From what we had been told about mass invasions, it took about a week to complete the landing of thirty ships.”

After the bombers had released their loads and turned for home, the Americans struck in strength.

Waiting for the Japanese were 18 F4F Wildcats and 16 Dauntless dive bombers operating from the aircraft carriers Enterprise, Wasp, and Saratoga, During the action, Lieutenant Sasai claimed the downing of five Wildcats. During a subsequent strike on Henderson Field, while leading eight Zeros in escort of a force of Betty bombers, Sasai was shot down by Marine Corps Major Marion E. Carl of squadron VMF-223. Sasai had previously run up a score of 27 aerial victories. Major Carl was the first Marine ace of World War II and ended the war with 18.5 confirmed kills.

Sakai recalled, “Without warning a group of enemy fighters jumped our formations from above. We could see the tracers spitting through our formations. With this first burst of fire, the fighter planes on both sides, about thirty in all, instantly broke formation. Planes scattered in all directions as our Zeros tried to break free of the attacking enemy…. As I pushed the stick hard over and rolled away, I noticed several aircraft plunging earthward, trailing streaks of black smoke … far below, I saw three Zeros pursued by a single enemy fighter. The Zeros were trying desperately to escape from the enemy plane, but the enemy pilot hung doggedly on their tails. The Zeros looked like my boys: Hatori, Yonekawa, and another pilot.”

It was a wild dogfight, the aircraft flying tight spirals. Sakai noted, “The Zeros should have been able to take the lone Grumman without any trouble, but every time a Zero caught the Wildcat before its guns the enemy plane flipped away and came out again on the tail of a Zero. I had never seen such flying before.”

Sakai took his plane into the melee and quickly found the Wildcat on his tail. But Sakai chopped his throttle and made an effort to maneuver his Zero into a firing position. He recalled, “Three times I rolled the Zero, then dropped in a spin, and came out in a left vertical spin. The Wildcat matched me turn for turn…. Neither of us could gain an advantage. We held to the spiral…. My heart pounded wildly, and my head felt as if it weighed a ton. A gray film seemed to be clouding over my eyes. I gritted my teeth; if the enemy pilot could take the punishment, so could I. The man who failed first and turned in any other direction to ease the pressure would be finished.”

Lieutenant James “Pug” Southerland was commanding a group of eight American Wildcats from the Saratoga, part of Fighter Squadron VF-5. Southerland and his flight had intercepted the Japanese bombers, and he claimed a Betty in the initial encounter. After shooting down a second bomber, Southerland was engaged in a dogfight with a Zero piloted by Japanese fighter ace Yamazaki Ichirobei. He lined up the Zero in his sights only to find his guns would not fire, probably due to damage from fire by the tail-gunner of the second bomber he had downed. Although defenseless, Southerland had to stay in the fight. Two more Zeros engaged him, flown by veteran pilots Kakimoto Enji and Uto Kazushi, but he was able to outmaneuver all three. This was the dogfight Sakai spotted.

“In desperation, I snapped out a burst,” Sakai remembered. “At once the Grumman snapped away in a roll to the right, clawed around in a tight turn, and ended up in a climb straight at my own plane. Never before had I seen an enemy plane move so quickly or gracefully before, and every second his guns were moving closer to the belly of my fighter. I snap-rolled in an effort to throw him off. He would not be shaken. He was using my favorite tactics, coming up from under.”

The Wildcat broke away, the aircraft going into a dive and then looping. Sakai cut inside the Wildcat’s arc and got on his tail. The F4F made a series of loops, Sakai cutting inside each, reducing the distance between the two planes. When he had managed to cut it to just 50 yards, the Wildcat broke out of the loop and flew straight and level. Sakai pumped 200 machine gun rounds into him but was amazed when the Wildcat continued to fly on as if nothing had happened. In an effort to overtake the American fighter he increased speed, but then overshot and found himself in its path and possibly the guns of the Wildcat. But to Sakai’s surprise there was no enemy fire. Dropping his speed, Sakai maneuvered alongside the American. For a few seconds the two adversaries eyed each other.

The pair maneuvered for several minutes until Sakai was able to put 20mm cannon shells into the F4F’s left wing root.

Southerland later wrote, “My plane was in bad shape but still performing nicely in low blower, full throttle, and full low pitch. Flaps and radio had been put out of commission…. The after part of my fuselage was like a sieve. She was still smoking from incendiary but not on fire. All of the ammunition box covers on my left wing were gone and 20mm explosives had torn some gaping holes in its upper surface…. My instrument panel was badly shot up, goggles on my forehead had been shattered, my rear-view mirror was broken, my plexiglass windshield was riddled. The leak-proof tanks had apparently been punctured many times as some fuel had leaked down into the bottom of the cockpit even though there was no steady leakage. My oil tank had been punctured and oil was pouring down my right leg. At this time a Zero making a run from the port quarter put a burst in just under the left wing root and good old 5F-12 finally exploded. I think the explosion occurred from gasoline vapor. The flash was below and forward of my left foot.”

Sakai remembered, “The Wildcat was a shambles. Bullet holes had cut the fuselage and wings up from one end to the other. The skin of the rudder was gone, and the metal ribs stuck out like a skeleton…. I raised my left hand and shook my fist at him…. The American looked startled; he raised his right hand weakly and waved.”

Sakai maneuvered behind the Wildcat and put several cannon rounds into its engine, causing it to burst into flames. In the next moment, the F4F rolled and the pilot bailed out. Southerland was able to parachute to safety.

As Sakai returned to 7,000 feet, three other Zeros joined him. As they flew through broken clouds they were taken by surprise by an enemy aircraft. Sakai recalled, “For the first time in all my years of combat, an enemy plane caught me unawares.” But in another surprise, Sakai realized that it was not a fighter, but a Dauntless dive bomber. Sakai took after the SBD and was able to shoot it down, claiming it as his 60th kill. The aircraft was piloted by Lieutenant Dudley Adams of Scouting Squadron 71 (VS-71) from the carrier Wasp. Adams scored a near miss, sending a bullet through Sakai’s canopy, but Sakai quickly gained the upper hand and succeeded in downing Adams, who bailed out and survived. However, his gunner, Harry Elliot, was killed.

Climbing back to 13,000 feet, Sakai and the other Zeros turned toward Guadalcanal. Sakai noted, “A few minutes later, over the Guadalcanal coast, I spotted a cluster of planes several miles ahead of our own. I signaled the other fighters and gunned the engine. Soon I made out eight planes in all, flying a formation of two flights.”

The enemy planes were in a tight formation. Sakai approached from behind and below. Closing the range rapidly, he was within less than 100 yards when he realized that the enemy aircraft were not fighters, but Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers — his first encounter with them. This was a flight from Bombing Squadrons Five and Six (VB-5 and VB-6). Unable to turn away without exposing his aircraft to enemy fire, Sakai fired first. Two of the Avengers fired in return with their ventral-mounted .30-cal. machine guns. In the next moment a violent explosion shook Sakai’s aircraft. A .30-cal. machine-gun round destroyed the canopy of Sakai’s Zero. His fellow pilots later reported that Sakai’s attack brought down two of the Avengers, but American records indicated that no TBFs were lost.

Sakai lost consciousness for a few seconds, but a strong, cold wind blowing through his shattered windshield brought him to. However, his vision was blurred as he drifted in and out of consciousness. He wasn’t feeling any pain, but thought he was dying. He gradually became aware of the world around him, his aircraft plunging earthward. Though groggy, he was able to pull his Zero out of the dive. He realized that he was blind in one eye with blurry vision in the other. He thought his chances of making it back to Rabaul were slim.

“I tried to move the engine throttle lever,” the wounded pilot remembered. “My left hand was totally numb…. When I attempted to press on the rudder pedals to correct the Zero’s awkward flight, I discovered that my left leg also was numb. Suddenly, I felt in my head a terrible, agonizing pain, which left me weak and breathless. I reached up and uneasily probed about my head with my right hand; it came away sticky with blood.”

With his fuzzy vision Sakai was able to make out the shapes of his instruments but not able to actually read them. Then, large dark shapes flashed past his wing. “They had to be enemy ships,” he later said. “That meant I was only about 300 feet over the water. Then sound came to me. First I heard the drone of the engine, then sharp, staccato cracks. The ships were firing at me! The Zero rocked with the blast waves of the bursting flak!”

Thinking that this was the end for him, Sakai considered making a suicide dive into one of the American ships. With this thought he was able to regain a measure of calmness and to assess the condition of his aircraft while also having mixed thoughts about the last few minutes. He had shot down several enemy planes and now was about to share the same fate. “I have finally met the American Navy planes which I have long been looking for,” he thought. “There is nothing I have to regret. It was at this moment that I began to weigh the possibilities of life or death.”

Sakai forced himself to stay awake. He did not want to go quietly but cried out for the Wildcats to come on and fight. In a few moments he came to his senses, realizing that he might survive despite the long flight back to Rabaul.

Sakai circled aimlessly, expecting to be attacked at any moment. As his head continued to clear and he was able to see better with his left eye, he checked his aircraft again and determined that he might be able to gain altitude, and with some luck reach Shortland Island, Buka, maybe even Rabaul.

Removing his gloves he examined his head wounds. He was still bleeding. A medical examination would later find two machine gun bullets lodged in his skull along with many small fragments. He had trouble making out his compass because of his blind right eye. Using the sun’s position in the sky he set course for Shortland. “Throughout the growing hopelessness of my situation, the only consolation was the amazing fact that the airplane, somehow, managed to keep on flying, despite the great damage it had suffered,” he recalled. “By all reasoning, the fighter should have crashed long ago.”

At times Sakai was ready to yield to the situation. He thought: “If I must die, at least I could go out as a Samurai. My death would take several of the enemy with me.” Again he turned his aircraft back toward Guadalcanal with the thought of seeking out an enemy ship to crash into. But he was unable to make up his mind, changing direction at least 10 times. Finally, he decided to head for Rabaul, but he was uncertain of his present position. Relying on only his sense of direction he pointed his Zero north. Concerned about running out of fuel, he desperately sought landmarks for navigation assistance. Suddenly, he spotted the atoll at Green Island, just 60 miles east of Rabaul.

At times Sakai was ready to yield to the situation. He thought: “If I must die, at least I could go out as a Samurai. My death would take several of the enemy with me.” Again he turned his aircraft back toward Guadalcanal with the thought of seeking out an enemy ship to crash into. But he was unable to make up his mind, changing direction at least 10 times. Finally, he decided to head for Rabaul, but he was uncertain of his present position. Relying on only his sense of direction he pointed his Zero north. Concerned about running out of fuel, he desperately sought landmarks for navigation assistance. Suddenly, he spotted the atoll at Green Island, just 60 miles east of Rabaul.

As he flew down the George Channel between New Britain and New Ireland, two warships, heavy cruisers, appeared ahead of him. He considered ditching right there. His hope was ebbing. He circled once over the warships but could not bring himself to do it. He turned toward Rabaul. If he could not make the airfields there, he considered crash landing on the beach. But then his airfield came in sight.

Those pilots that had already returned from the mission were extremely surprised to see Sakai’s Zero circle over the field. He turned away on his first landing attempt. He circled the field four times, his fuel running low, before making his final approach. He put his Zero down on the runway on his second attempt. After bringing his plane to a safe stop, he passed out. When he came to, he insisted on making his mission report to his commander before collapsing.

Sakai had flown his aircraft for nearly nine hours, engaged four enemy planes, and covered over 560 miles while he struggled to stay alive. His success (and survival) was due in no small part to the engineering quality of his aircraft, as well as his skill and will to live. Sakai was evacuated to Japan on August 12, where he underwent surgery. He was hospitalized for a year after the battle. He never regained sight in his right eye. In a way, he was lucky to have suffered his wounds on the first day of action over Guadalcanal, as many of his fellow pilots would not survive the campaign.

After his discharge from the hospital in January 1943, Sakai spent a year training new fighter pilots. When it became clear that Japan was losing the war, he prevailed upon his superiors to let him fly in combat again. In November 1943, Sakai was promoted to the rank of flying warrant officer. In April 1944, he was transferred to the Yokosuka Air Wing, which was deployed to Iwo Jima.

On June 24, 1944, Sakai approached a formation of 15 U.S. Navy Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, which he mistakenly believed were Japanese aircraft. Four of the Hellcats went after the Zero, but Sakai, using his skill and experience, eluded the Hellcats and was able to return safely to his base.

In air combat over Iwo Jima, he reportedly shot down four American planes. When his aircraft was destroyed on the ground by a U.S. air strike, he was flown off the island in a courier plane.

After the war, Sakai became a Buddhist acolyte. Like many veterans, his feelings about war and his country’s former enemies softened. He sent his daughter to college in the United States. Following a U.S. Navy formal dinner in 2000 at Atsugi Naval Air Station, where he had been an honored guest, Sakai died of a heart attack at the age of 84.

Author Allyn Vannoy has written extensively on a variety of topics related to World War II. He resides in Hillsboro, Oregon.